22 Years Later, US Still Classifying “Bombshell” Plan to Pull Peacekeepers Out Before Rwanda Genocide

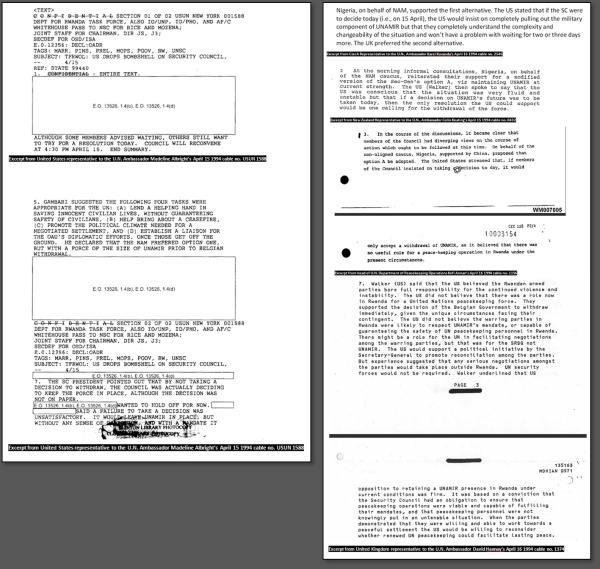

Left: Redacted State Department “bombshell” document, Right: Excerpts from cables reporting on the “bombshell” from the Czech Republic, New Zealand, United Kingdom, and the United Nations’ Kofi Annan.

The tinderbox of Rwanda’s ethnic tensions ignited in April 1994 and mass violence engulfed the country in one of the swiftest campaigns of genocide in history. The National Security Archive’s Genocide Documentation Project’s collection of declassified documents on Rwanda numbers in the thousands, and includes an April 15, 1994, State Department cable on the U.S.’s decision to pull United Nations forces out of Rwanda; a fact still withheld by State Department redactors even though the information has been released by the Czech Republic, New Zealand, United Kingdom, and the United Nations and published on the Archive’s website.

On April 20, 1994, the Advisor on African Affairs to French President Mitterrand, Bruno Delaye, stated, “There is nothing to say.” According to UNHCR, 100,000 Rwandans would be dead by the end of April and 800,000 would be displaced. The following day, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) reported that the fighting that started in central Rwanda at the beginning of the month had spread to the rest of the country. Tens of thousands were dead and hundreds of thousands had fled their homes.

However, a plan by the U.S. and the UN to reduce and eventually withdraw the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) was already well underway. On April 15, 1994, the U.S. Mission to the UN dropped a “bombshell” on the Security Council, arguing for the complete termination of UNAMIR and the pullout of all peacekeepers in Rwanda.

Reviewers redacted the historic “bombshell” from a State Department cable, however, even though the fact that the U.S. called for the withdrawal of UNAMIR troops, was previously released to the National Security Archive by the governments of the Czech Republic, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom, and the UN’s Kofi Annan in response to FOIA requests. The information had even been published on the Archive’s website and in the critical oral history conference briefing book, “International Decision-Making in the Age of Genocide: Rwanda 1990-1994,” in June 2014.

Declassified notes from a April 21, 1994, Peacekeeping Core Group meeting, written by Susan Rice, detailing discussions surrounding the withdrawal of UN peacekeeping forces from Rwanda.

On April 21, 1994, the same day of the ICRC report, Susan Rice, then the deputy to Richard Clarke of the National Security Council, attended a meeting of the Peacekeeping Core Group (PCG). Her handwritten notes stated, “[Maurice] Barril wants to withdraw 900 tonight,” followed by concerns about setting a “bad precedent, potentially.”1 She then begs the question, “How do we protect people if forces are withdrawn?”

Rice’s prescient notes, among hundreds of pages of other pertinent documents, were declassified in 2015 after the Archive sent a Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR) request to the Clinton Presidential Library, and can be found in the Clinton Digital Library.

The same day of the PCG meeting, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 912, which cut the size of UNAMIR forces down to 270 people. An April 26, 1994, declassified State Department cable described the policy as, “retain[ing] a small group, including the Force Commander and SRSG, with necessary staff, an infantry company to provide security, and some military observers.”

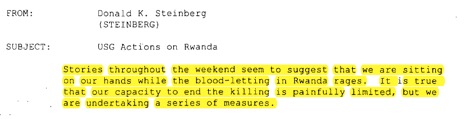

An April 25, 1994, confidential National Security Council memo from Donald Steinberg, the Council’s Senior Director for African Affairs, reads, “Stories throughout the weekend seem to suggest that we are sitting on our hands while the blood-letting in Rwanda rages. It is true that our capacity to end the killing is painfully limited, but we are undertaking a series of measures.”

An April 25, 1994, confidential memo to the National Security Council addresses the perception that the U.S. was “sitting on [their] hands” during the genocide.

In a September 2001 interview, Susan Rice said:

There was such a huge disconnect between the logic of each of the decisions we took along the way during the genocide and the moral consequences of the decisions taken collectively. I swore to myself that if I ever faced such a crisis again, I would come down on the side of dramatic action, going down in flames if that was required.

The Genocide Project’s conference at The Hague in June 2014, in partnership with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, assessed these policy decisions with key actors and added to the historical record of the Rwandan Genocide, a record that should not, 22 years later, continue to be hampered by needless secrecy of historically important documents like the “bombshell” cable.

UN Peacekeeping Troops in Rwanda circa September 1994. Photo from personal collection of Prudence Bushnell.

The Genocide Documentation Project, launched in January 2013 in partnership with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, explores the failures of the international community to prevent or effectively respond to past cases of genocide. Through detailed case studies, the project’s research seeks to inform international policies regarding the prevention of and response to genocide and mass atrocity. By examining the role of the international community in past incidents of genocidal violence, these case studies help shape the views of a new generation of policymakers both within the United States and around the world.

1. Major General Maurice Barril was the military advisor to UN Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali and in charge of the Military Division of the Department of Peacekeeping Operations during the genocide.

↩

Trackbacks

- nsarchive.wordpress.com: US Plan to Pull Peacekeepers Out Before Rwanda Genocide | UNREDACTED | [Modern Times]

- Intersect Alert May 1, 2016 | SLA San Francisco Bay Region Chapter

Comments are closed.

“Bill Clinton Regrets Rwanda Now (Not So Much In 1994): …

LINK: http://abcnews.go.com/blogs/politics/2014/02/bill-clinton-regrets-rwanda-now-not-so-much-in-1994/