John Moss and the Roots of the Freedom of Information Act: Worldwide Implications

By Michael R. Lemov* & Nate Jones**

This article originally appeared in the Southwestern Journal of International Law, Volume 24.

INTRODUCTION

John Moss was an obscure Congressman from a newly created district in northern California when he arrived in Washington D.C. in 1953.1 He had survived a razor-thin general election victory (by about 700 votes), which included unfounded charges of being a communist, or a communist sympathizer.2 Those charges became an important force behind Moss’s long battle to enact the Freedom of Information Act.

Except for an 18th century Swedish law and a similar information law in Finland in 1951, the U.S. Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) was the first open government law in the world.3 During the twelve years it took John Moss to win enough Congressional votes to pass the bill, he endured intense political opposition, faced a veto threat from a president of his own party, and overcame fierce opposition from executive branch agencies.4

When President Lyndon Johnson signed the Freedom of Information Act into law on July 4, 1966, Moss did not receive a pen from the president, nor was there any signing ceremony.5

Since 1966, more than 117 nations have passed government information laws.6 Congress has amended and refined significant sections of the U.S. law several times, generally improving access in areas where Moss had to compromise in order to win its original passage.

I. MOSS AND THE CONGRESS

When Moss first arrived in Washington, D.C. there was a poisonous political atmosphere in the city.7 Senator Joseph McCarthy was riding anti-communist fears that he helped arouse and that propelled him to great influence in the U.S. Senate and in the nation.8 The House Un-American Activities Committee was making headlines, with its endless investigations of security risks, Russian spies, and alleged disloyalty in dozens of government agencies and American industries.9

President Harry Truman issued an Executive Order establishing an administration Loyalty Program.10 It directed Truman’s attorney general to compile a list of communist organizations and “front” organizations and to investigate the loyalty of federal government employees.11 Based on the results of these investigations, the targets could be fired from their government jobs, prosecuted, and made virtually unemployable.12 They faced public condemnation and personal humiliation in the process. People investigated under the Loyalty Program were not allowed to confront their accusers or see the charges against them, often based on hearsay evidence that was held in secret files compiled by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.13

United States Court of Appeals Judge Henry Edgerton wrote an opinion concerning the firing of one such government employee: “Without trial by jury, without evidence, and without even being allowed to confront her accusers or to know their identity, a citizen of the United States has been found disloyal to the government of the United States.”14 Edgerton found the discharge proceedings to have been unconstitutional.15 “Whatever her actual thoughts may have been,” he wrote, “to oust her as disloyal without trial is to pay too much for protection against any harm that could possibly be done.”116

Edgerton was the lone dissenter on the federal Court of Appeals. The court affirmed the employee’s firing from government service.17 The United States Supreme Court divided evenly in reviewing the case, four to four, thus upholding the legality of the Truman Loyalty Program and its attendant government secrecy.18

Moss knew about the McCarthy approach, having been a target of similar charges in his California campaigns for both the state assembly in 1949 and, in 1953, for Congress.19 He survived the attacks. He did not forget them. His long campaign to secure freedom of information was grounded, in part, on his anger at being faced with such potentially devastating charges based on unsubstantiated claims against him.

Moss’s information battle was also based, coincidentally, on his assignment to a very obscure congressional committee that had legislative responsibility only for federal civil service and post office employees.20

When he took his seat in Congress in January 1953 representing California’s new Third Congressional District, there was no evidence that limiting government secrecy and providing the public and the press with access to government records would be causes he would champion for twelve long years—and in fact, for the rest of his life.21 Perhaps because of Moss’s independent views on several such issues, he later said, “By all that was holy, I was destined to be a onetermer.”22

But Moss and his new congressional district in Sacramento bonded almost instantly. The strong connection had started with his election to the California Assembly in 1949 in a portion of the Third district.23 Moss had a clear record. He favored lower utility rates for consumers, strengthening public power to compete with the giant Pacific Gas and Electric Company, increased wages for government workers, and better working conditions for railroad employees.24 His stances on the issues were a natural fit for Sacramento’s voters, who appeared to like his combative style and his populist position on pocketbook issues. Moss was repeatedly returned to office in Sacramento for thirty years.25

The young congressman knew about everyday problems from his own experience—particularly the sudden death of his mother when he was a small boy—and his subsequent abandonment by his father. Living in an attic with his older brother, he struggled financially to go to high school and never finished college.26 He later said, “[I] gained all of my bits and pieces of knowledge and understanding the more difficult way . . . but at the same time, it made me appreciate them more, and I probably dug deeper to get some of the facts.”27

In the nation’s capital in 1953, Moss was an unknown. He tried for an appointment to the powerful House Commerce Committee, or to the Government Operations Committee.28 He was assigned instead to the Post Office-Civil Service and House Administration Committees.29 These were not exactly major appointments, but freshmen are typically placed on such minor committees.30 So he waited and did his best to make something of his position, serving out his “sentence” stoically and as it turned out, productively. He offered and pushed through amendments that gave post office workers the right to arbitration of disputes and a pay raise.31

II. THE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE

At the end of Moss’s second term in 1956, the House Leadership promoted him to membership on the more powerful Government Operations Committee, which had jurisdiction over government information practices.32 He would serve on Government Operations for twenty-two years.33

But Moss wanted even more—a seat on another and perhaps more influential committee.34 Moss let the California delegation know he was interested in membership on the Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee as well as Government Operations.35 He wanted Commerce because it had jurisdiction over major parts of business and industry in the United States and trade with foreign nations.36 Before running for Congress, Moss had been in the appliance and real estate businesses in Sacramento.37 He thought he knew something about commerce.38 So the committee’s jurisdiction over transportation, communications, securities markets, consumer protection, energy, the environment, and health care appealed to him.

Moss was disappointed when the selections of the Democratic caucus were announced.39 Sam Rayburn, the all-powerful Texas Congressman who was Speaker of the House, “always liked to pick Texans for key committees[,] . . . he didn’t particularly look to California.”40 So Moss tried again, this time directly with Speaker Rayburn.

He walked from the House office building across the street to the Capitol to talk to the Speaker.41 From the way Moss described it later, he did not press Rayburn but Moss reminded him that there was no Californian on the Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee; that he was from the growing northern part of the state; and that he probably would have the nomination of both parties in the next election— something he did not actually get until 1958.42 Moss assured Rayburn he knew about business issues; that he could handle the job; and that he really wanted it.43 And, oh yes, putting a Californian on Commerce might be good for the Democratic Party. Rayburn was nobody’s pushover. Moss found him friendly, but noncommittal.

A day or two later, Moss got a telephone call from the chairman of the California delegation: “You’re on the Commerce Committee, John. What the hell did you say to Rayburn?”44

It had not hurt Moss to go to the Speaker to make his case. The meeting began a strong relationship between the young Moss and the older, more powerful Rayburn.45 Rayburn placed Moss on the leadership track, eventually landing him as deputy whip.46 Rayburn also oversaw the appointment of Moss as chairman of the newly established Special Subcommittee on Government Information, which was established as a part of the Government Operations Committee.47 And it was Rayburn who, directly or indirectly, supported Moss’s long freedom of information battle.48

III. GROWTH OF GOVERNMENT SECRECY

World War II witnessed an immense growth of the federal government coupled with the wartime need for a high degree of secrecy— at least as to military-security information. Winning the war took precedence over everything. In the years immediately following World War II, the military’s need to guard and control information declined, but secrecy and censorship limiting the flow of government information to the public continued.49 During the Cold War and the anti-communist hysteria that followed, both the Truman and Eisenhower Administrations responded with many information and security restrictions, the Truman Loyalty Program among them.50 Some restrictions became what appeared to be a permanent apparatus for state secrecy.

Due to government and public reaction to the uncertainties of the Cold War, thousands of documents were classified as secret. The prevailing attitude towards government records was “when in doubt, classify.”51 Secrecy labels were slapped on seemingly innocent bits of data. For example, the amount of peanut butter consumed by the armed forces was classified as secret (the government feared this information might enable an enemy to determine our military preparedness). A twenty-year-old report describing shark attacks on shipwrecked sailors was classified as secret, as was a description of modern adaptations of the bow and arrow.52

In the midst of this wave of Cold War secrecy, Moss confronted executive branch secrecy for the first time.53 During his first term in Congress, while on the House Post Office and Civil Service Committee, Moss became concerned with the discharge of some 2,800 federal employees for alleged “security reasons.”54 Moss felt that the dismissals ought to be explained more thoroughly by the Civil Service Commission.55 The firings had a devastating effect on employees and reflected poorly on the civil service in general. Besides, Moss believed the majority of the people dismissed had probably not been let go because they lacked patriotism, but for other minor incidents or because of disagreements with their superiors. An instinctive civil libertarian, Moss was sensitive to questionable charges of disloyalty. So the young congressman, as a member of the committee with jurisdiction, formally requested that the Civil Service Commission produce the records relating to the discharge of all 2,800 employees.56 His request was flatly denied by the Civil Service Commission.57 It seemed as though that would be the end of it. With the Republicans in control of both the Executive Branch and Congress, he was stymied.58 But Moss did not forget the issue, or the affront.

IV. ROLE OF THE PRESS

The Cold War, the “red scare” and similar concerns continued to broaden government control over information. Kent Cooper, the executive director of the Associated Press, popularized the phrase “right to know” in his 1956 book by the same name.59 He wrote: “American newspapers do have the constitutional right to print . . . but they cannot properly serve the people if governments suppress the news.”60 Cooper cited a 1945 New York Times editorial that had referred to the “right to know” as a “good new phrase for an old freedom.”61

The American Society of Newspaper Editors (ASNE) organized a freedom of information committee in the late 1940s.62 The committee pressed to obtain access to government records but the levels of secrecy and the complexity of attempting to get facts from the now bloated federal government caused one of its chairmen to say that the situation “frightened [him] very, very much, because, for the first time, [he] really realized the perils that we face in this country.”63 Editors became so concerned about the denial of information to the press and the public that they commissioned Harold Cross, a leading newspaper lawyer and counsel to the New York Herald Tribune, to prepare a report on federal, state, and local information rights. Cross’s report was published in 1953 under the title, “The People’s Right to Know.”64 It was funded by ASNE.65

The Cross report confirmed press fears over the systematic denial of government information and asserted that the press and the public have an enforceable legal right to inspect government records for a lawful or proper purpose.66 In ringing terms, Cross spelled out a new constitutional and legal principle: “Public business is the public’s business. The people have the right to know. Freedom of information is their just heritage. Without that, the citizens of a democracy have but changed their kings.”67

The Cross report looked mainly at the state of the law as reflected in court decisions either granting or denying the right to access.68 It also focused primarily on state and local law because under existing federal law, “in the absence of a general or specific act of Congress,” there was absolutely no enforceable right of the public or the press to access government documents.69 The federal government was, in fact, subject to a series of statutes and regulations essentially making federal records and information the private property of each federal agency and ultimately of the White House.70

Thus, Cross’s book, which became the Bible of the press and ultimately a guide to the Congress regarding freedom of information, opened the way toward a more open government—but only in general terms.71 Cross said the First Amendment “points the way[;] [t]he function of the press is to carry the torch.”72 Where to carry the torch and how to secure such a public right to government information remained unclear.

Just after the publication of Cross’s book, the Eisenhower Administration precipitated an incident that gave the issue of control of government information and public access to such information more national prominence and a new leader.73

In 1954, the voters returned a Democratic Congress to Washington.74 Around the same time, President Eisenhower created the Office of Strategic Information (OSI).75 The OSI was officially established in the Department of Commerce at the request of the National Security Council.76 It quickly became controversial.

The idea was to ask industry and the press to “voluntarily” refrain from disclosing any strategic information that might assist enemies of the United States.77 At that time, the primary enemy was, of course, the Soviet Union. The chill of the Cold War dominated the American consciousness. OSI’s new director was R. Karl Honaman, who later moved to the Department of Defense under Secretary of Defense Charles Wilson.78

On March 29, 1955, Defense Secretary Wilson issued a directive to all government officials and defense contractors stating that, in order for an item to be cleared for publication or released to the public, it not only had to meet security requirements, but also had to make a “constructive contribution” to defense and national security.79 Under this standard, the government would have had almost total control over all information released and, at the time, there was no possibility of court review of such decisions.80

This new barrier of government secrecy infuriated editors, reporters, and the press generally.81 Editorials were published opposing the Eisenhower Administration’s information policy.82 Time magazine commented that “such a policy is just the thing for government officials who want to cover up their own mistakes by withholding nonconstructive news.”83

J.R. Wiggins of the Washington Post and chairman of the ASNE government information committee, said “newspapers will not join in the conspiracy with this or any other administration to withhold from the American people non-classified information.”84 The public battle between the Eisenhower Administration and the press could not help but come to the attention of the newly-elected Democratic Congress—and to interested members like Moss.85

One historian later noted that the battle may have precipitated the most important event on the path to the Freedom of Information Act; that event was the creation of a Special Subcommittee on Government Information in 1955, thereafter known as the “Moss Subcommittee.”86

Some evidence suggests that Moss became interested in the denial of information to the press and public in 1955 when he met with press lawyer and author Harold Cross.87 It was perhaps Moss’s own experience with the Civil Service Commission’s roadblock to his information requests and Cross’s eloquence that merged the strands of the issue for Moss. The controversy also came up at a moment in time when the political climate was ripe for at least an inquiry into the problem of access to government information.

V. CREATION OF THE SPECIAL SUBCOMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT INFORMATION

From his new position as a junior member of the Government Operations Committee, Moss saw a chance to deal with an issue that he cared about a lot and that affected many.88 A short time after his appointment, Moss talked with William Dawson, the chairman of the Government Operations Committee, and suggested that the committee authorize a “study” to determine the extent of information withheld by the Executive Branch.89

Moss’s sense of the right of the public, as well as the prerogatives of the Congress, undoubtedly fueled his interest in freedom of information. His meetings with editors, reporters, and author Harold Cross increased his interest.90 And he read the newspapers, as did the leadership.91 They thought that secrecy in government could be a potentially powerful political issue.92 Moss directed Dr. Wallace Parks, a committee counsel, to undertake a preliminary inquiry.93 Parks, who later became counsel to Moss’s Government Information Subcommittee, wrote a memorandum—undoubtedly with Moss’s supervision—to committee chairman Dawson, indicating that there was indeed a trend toward suppression and denial of access to government information, that it was growing, and that it affected areas of government untouched by security considerations.94 What happened next can only have been authorized by Speaker Rayburn.

In an effort to solicit support for a new subcommittee on government information and withholding, Moss and Parks, armed with their memorandum, approached House leadership through Majority Leader John McCormick of Massachusetts.95 According to a committee staff member at the time, McCormick, Rayburn, and others in the leadership were “pushed out of shape because the Administration was withholding information from Congress. [They] wanted to get the press aroused over the issue so [that the Administration would be pressured on behalf of Congress] . . . .”96 Moss, with his progressive attitudes and willingness to tackle big interests, clearly thought more broadly than access solely by the Congress.97

With the support of McCormick and Rayburn, a new Special Subcommittee on Government Information was established on June 9, 1955.98 A memorandum from Chairman Dawson—again written by Parks under Moss’s direction—noted that, “An informed public makes the difference between mob rule and democratic government. . . . I am asking your Subcommittee to make such an investigation as will verify or refute these charges.”99

The chairman of the new and potentially powerful Special Subcommittee on Government Information might have been any one of several senior members of the House. It was, instead, the very junior representative from California, John Moss.100

Why would the Democratic leadership of the new Congress place responsibility for the chairmanship of such a potentially powerful subcommittee in the hands of a second-term congressman? Only Rayburn, McCormick, and Moss know the answer to that question and they are long gone. But Moss’s early willingness to tackle big problems, demonstrated both in the California legislature and on the Post Office and Civil Service Committee, may have played a role. Leadership might have noted Moss’s intense interest in the subject and his personal drive. Otherwise, perhaps, Rayburn just liked the young congressman.

Moss’s sudden rise to a key House position may have simply been a case of the right leader appearing at the right time. One thing is certain, Moss thought there was a job to be done and he wanted the job “desperately.”101 Whatever the reason, when he assumed the chairmanship of the new Special Subcommittee on Government Information, Moss could not have known the true extent of the struggle that he had embarked upon, nor how long, and how difficult that battle would be.

VI. SUBSTANTIVE AND POLITICAL OPPOSITION TO FOIA

Ten years after being named chairman of the Special Subcommittee on Government Information in 1955, and eleven years after confronting the federal government’s wall of secrecy over alleged employee disloyalty, Moss was still struggling to move a freedom of information bill out of the House of Representatives.102 He had spent most of these years in Congress immersed in a seemingly endless investigation of what he considered mostly unjustified government refusals to give up information and in an effort to write a bill that could become law.103 In numerous hearings, he targeted “silly secrecy,” or the Government’s refusal to disclose such vital data, as: the modern uses of the bow and arrow and the amount of peanut butter consumed by United States soldiers.104

Most of the subcommittee investigations, hearings, and reports resulted in confrontations with federal agencies that did not want to give his subcommittee, and the public, information from agency files.105 Every federal agency that testified before the subcommittee opposed what was then known as the “federal records law.”106

Moss believed that he was fighting a denial of a basic right.107 But that right was not, and still is not, spelled out in the Constitution. The right to obtain information can only be inferred from the right to speak freely under the First Amendment to the Constitution. Moss wondered—perhaps doubted—if Congress would ever guarantee what most people incorrectly thought was already a part of the right to free speech under the First Amendment.108

In 1965, as Moss opened hearings on what would be the final, dramatic struggle over the public information law, he noted that there now was a “legal void” into which executive agencies had moved because of Congress’s failure to guarantee a fundamental right.109

He also recognized that the issue touched a very sensitive nerve of the executive branch, especially with the president. President Lyndon Johnson did not lean favorably towards increased access to government information.110 The respected New York Times columnist Arthur Krock described Johnson’s attitude as “tight official lip.”111 Johnson not only distrusted the press but, “was convinced that the press hated him and wanted to bring him down.”112

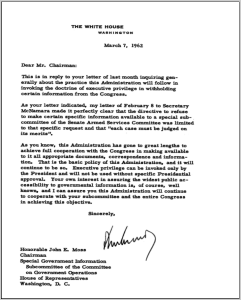

Kennedy’s March 1962 letter to Moss agreeing to assert executive privilege only personally and not delegate the power to lower-level officials.

Moss, responding to such concerns, said that, “no one supporting the legislation would want to throw open Government files which would expose national defense plans to hostile eyes.”113 But at the same time, the government should not “impose the iron hand of censorship on routine Government information.”114 Between these extremes, Moss suggested, there might be an opening for compromise, one which had thus far eluded Congress and his subcommittee.115 Moss knew that, if the bill ever made it to the White House, he did not have the votes to override a presidential veto.116

The final round of hearings on the bill was courteously conducted. Beneath the calm lurked a major confrontation between the President and Congress. A key witness for the executive position came from the Department of Justice, Assistant Attorney General Norbert A. Schlei, testifying on behalf of the White House as well as the Justice Department.117 Schlei stated that the proposed law was unconstitutional because it impinged on the power of the president to keep information secret when release was “not in accord with his judgment of what was in the public interest.”118

Because of the “scope and complexity of modern government,” Schlei said, “there are, literally, an infinite number of situations wherein information in the hands of government must be afforded varying degrees of protection against public disclosure. The possibilities of injury to private and public interests through ill-considered publication are limitless.”119 Highly sensitive FBI reports containing the names of undercover agents and informers, for example, were protected only by the president’s claimed right of “executive privilege” and ancient legal precedent. The subject was just too complicated, too changing, to be covered by any system of legal rules.120

Schlei predicted that Moss’s bill would destroy the delicate balance between Congress and the Executive Branch, and that the legislation would eliminate “any application of judgment to questions of disclosure or nondisclosure . . . .”121 It would substitute a single legal rule that would automatically determine the availability, to any person, of all records in the possession of federal agencies—except Congress and the courts, which were excluded from Moss’s bill. That approach, according to the Justice Department representative, was impossible and could only be fatal.122 There was no way of eliminating judgment from the process used to resolve the problem. “The problem is too vast, too protean to yield to any such solution.”123

Schlei’s testimony ended with an apparent veto threat.124 Moss’s bill, Schlei said, impinged on the authority of the president to withhold documents where he determined that secrecy is in the public interest.125 Since the bill would contravene the Separation of Powers Doctrine, it would be unconstitutional.126 Neither the Department of Justice, nor its spokesman, discussed the scope of the claimed executive privilege right—which is not explicitly referred to in the Constitution.127 Nor did the Justice Department indicate how the term “in the public interest” could be defined.

Moss challenged the witness and, through him, the president. He said the problem they were dealing with would not go away anytime soon.128 He recalled that the House and the Senate had been working on a freedom of information law for many years.129 The Senate had recently passed a bill identical to Moss’s House proposal and written by Moss’s staff. Moss asserted, “[W]e have not been impetuous here. Ten years in moving to a piece of legislation is rather a long period of time. . . . [T]his step can be taken now and . . . it will succeed . . . .”130

One of Moss’s strongest congressional backers was a freshman Republican congressman from Illinois named Donald Rumsfeld. Rumsfeld, years later a secretary of defense with a very different perspective on information disclosure, not only supported Moss at the hearings, he also maintained his support with speeches on the House floor.131 According to Bruce Ladd, a member of his staff, Rumsfeld convinced Minority Leader Gerald Ford and the House Republican Policy Committee to back the bill.132 They attacked the Johnson Administration for not supporting it, although they had been strangely silent on the issue during the Eisenhower Administration.133 The political stakes over the proposed Freedom of Information Act were growing.134

VII. TACTICS: THE LONG INVESTIGATION

The Special Subcommittee on Government Information had been created in 1955 with little public notice.135 The issue of freedom of information versus government secrecy had not yet gained public traction ten years earlier.

The press, however, had long been frustrated by its inability to get government documents. As far back as the 1940s, the ASNE established a Freedom of Information Committee. Initially chaired by James Pope, editor of the Louisville Journal, it commissioned the landmark study by Harold Cross, the Herald Tribune counsel, which was published in 1953.136 Pope said, in a forward to the Cross book: “[W]e had only the foggiest idea of whence sprang the blossoming Washington legend that agency and department heads enjoyed a sort of personal ownership of news about their units. We knew it was all wrong, but we didn’t know how to start the battle for reformation.”137

Cross had opened his report with ringing statements of conviction: “Citizens of a self-governing society must have the legal right to examine and investigate the conduct of its affairs, subject only to those limitations imposed by the most urgent necessity. To that end they must have the right to simple, speedy enforcement . . . .”138 Cross cited Patrick Henry’s statement at the dawn of the Republic: “To cover with the veil of secrecy the common routine of business is an abomination in the eyes of every intelligent man.”139

All that was missing was a workable plan of action. Even when Moss and his special subcommittee got started in November 1955, the press did not focus much attention on the early hearings. As Congressional Quarterly reported, representatives of the press were asked to testify first before the subcommittee.140 Russell Wiggins of the Washington Post told the subcommittee that newspaper editors were disturbed by the withholding of information in many areas of government.141 “We think it is due to the size of Government . . . and . . . to declining faith in the wisdom of the people . . . .”142 James Reston, chief of the New York Times Washington bureau asserted that withholding information was part of a growing tendency by government officials to “manage” news that might harm their image.143 It was a barely concealed jab at Johnson.

Philip Young, chairman of the Civil Service Commission, countered that the commission, not just the president, had inherent power under the Constitution to withhold information from Congress, the press, and the public.144 Officials of several government agencies testified that, if transactions or even conferences with private businesses were made public, it would be difficult to obtain frank disclosures and recommendations.145

Less than a year after its creation, the Moss subcommittee forwarded its first “interim” report.146 The idea was to energize members of Congress by telling them what the Executive Branch was doing. The staff report noted that the heads of departments often failed to furnish information even to Congress, based on a “naked claim of privilege.”147 At that time, the staff was headed by two newspapermen, Sam Archibald and Jack Matteson.148 Their report argued that “Judicial precedent recognizes the power of Congress to grant control over official government information . . . If Congress can grant control . . . it follows that it can also regulate the release of such information . . . .”149

The Department of Justice submitted a 102-page rebuttal.150 It is hard to conceive of a federal agency asserting any similar definition of unbridled executive power today: “Congress cannot under the Constitution compel heads of departments to make public what the president desires to keep a secret in the public interest. The president alone is the judge of that interest and is accountable only to his country . . . and to his conscience.”151

As the dispute grew more intense, Moss suggested that if the Department of Justice was right, “Congress might as well fold up its tent and go home.”152

Defense Department officials were prominent witnesses before the Moss subcommittee.153 With the Vietnam War expanding and the Cold War still raging, national security fears were a major part of the information debate. Assistant Secretary Robert Ross did offer a minor concession.154He said that in the department’s recently issued directive, information must make a “constructive contribution to the defense effort or it could not be released.”155 That said, he added that it did not apply to press inquiries.156 He did not mention inquires by Congress or members of the public.

Another witness, Trevor Gardner, former assistant secretary of the Air Force, had resigned a few months prior, in protest against Defense Department information policies.157 He stunned the subcommittee, testifying that at least half of all currently classified defense department documents were not properly secret.158 Gardner gave an example of excessive secrecy by noting that a leading nuclear physicist—Robert Oppenheimer—had been denied security clearance by the Atomic Energy Commission in 1954.159 Inconveniently, Oppenheimer kept coming up with valuable, top secret nuclear ideas.160 Gardner thought keeping Oppenheimer uninformed was absurd.161

In July 1956, the Moss subcommittee issued its first formal report, which summed up its initial year of work.162 Despite the opposition of every federal agency that testified, the report concluded:

It, therefore, is now incumbent upon Congress to bring order out of the present chaos. Congress should establish a uniform and universal rule on information practices. This rule should authorize and require full disclosure of information, except for specific exceptions defined by statute or restricted delegation of authority to withhold for an assigned reason within the scope of the authority delegated. The withholding should be subject to judicial review and the burden of proof should be on the official who withholds information.163

Republican Congressman Claire Hoffman filed vigorous dissenting views to the report, asserting that the information powers of the president—Dwight Eisenhower—could not be lawfully limited.164

But the brief statement in the report by Moss and a nearly unanimous subcommittee, neatly summarized the heart of what was to become the Freedom of Information Act, an act that could not pass Congress for another ten long years. A Moss-Hennings amendment intended to limit the existing federal Housekeeping Law, giving ownership of records to executive agencies, did not change other federal laws, which were used to deny information to the public.165 Moss, Hennings, and their allies had failed to bargain on the tenacity of the federal bureaucracy—which had noted the reluctance voiced in President Eisenhower’s signing statement on the Moss-Hennings amendment.166The Housekeeping amendment was ignored. Federal agencies continued to cite other provisions of law authorizing them to withhold information, either because it was not in the “public interest,” the person claiming the information did not have a legitimate right to get it, or the information might impair national security.167 Rarely did President Eisenhower have to make a formal claim of executive privilege. That authority was delegated down the line to relatively low-level bureaucrats, who routinely blocked access to the public, the press, and Congress.

Another report, issued in 1966 by the full Committee on Government Operations in support of Moss’s proposed Freedom of Information Act, claimed that improper denials of information requests had occurred again and again for more than ten years through the administrations of both political parties.168 Case after case of withholding of information was documented. There was no adequate remedy.169

The 1966 report, approved by the full Government Operations Committee, noted many instances of questionable agency denials:

—The National Science Foundation decided it would not be in the “public interest” to disclose competing cost estimates submitted by bidders for the award of a multi-million dollar deep sea study;

—The Department of the Navy ruled that telephone directories fell within the category of information relating to “internal management” of the Navy and could not be released;

—The Postmaster General ruled that the public was not “directly concerned” in knowing the names and salaries of postal employees;

— Federal agencies refused to disclose the opinions of dissenting members, even where a vote on an issue had been taken; and

—The Board of Engineers for Rivers and Harbors, which ruled on billions of dollars of federal construction projects, said that “good cause” had not been shown to disclose the minutes of its meetings and the votes of its members on awarding contracts.170

The committee reported that requirements for publication were so hedged with restrictions that twenty-four separate terms were used by federal agencies to deny information.171 These included “top secret,” “secret,” “confidential,” “official use only,” “non-public,” “individual company data,” and a seemingly endless list of other words and phrases.172

VIII. OPPOSITION INCREASES

Proponents of a federal information law had other hurdles to overcome. There were efforts to deny the Moss subcommittee funding or completely eliminate it.173 The ASNE committee wrote to the Chairman of the Government Operations Committee, William Dawson, that “the importance of the Committee’s work cannot be exaggerated. . . . We who have seen the danger and the need are greatly heartened, and we would like to see the Committee’s funds, its powers and its influence vastly expanded.”174

The effort to de-fund the Moss committee did not succeed, but Moss faced other attempts to take away his committee powers. In 1965, near the end of his long investigation, Moss and his staff wrote and introduced a public information bill—identical to a Senate bill offered by Senator Edward Long of Missouri (after Senator Hennings’ death in 1960)—which would enact a freedom of information law similar to the one outlined in the subcommittee’s first report in 1955.175 But Moss’s progress was halted when, suddenly, he was unable to muster a quorum of subcommittee members necessary to vote on the bill.

When interviewed by the Albuquerque Journal about what was happening to the Moss bill, subcommittee member Donald Rumsfeld suggested that President Johnson’s opposition was the problem.176 According to the Albuquerque Journal reporter, when asked why the subcommittee could not get members to meet and vote on the bill, Rumsfeld answered, “We always managed to meet before.”177

Newspaper columnists Robert Alan and Paul Scott, writing in the Tulsa World, reported that the Johnson Administration was pushing to rewrite the bill to give the heads of all departments and agencies authority to bar publication of official information.178 An Associated Press story said that the president had passed the word to jettison the bill.179 Moss’s actions in continuing to force a quorum and in replacing the two absent subcommittee members showed he was determined to push the bill through, despite the apparent opposition of a president of his own party and, perhaps, of the seemingly conflicted House leadership.

The Washington Post editorialized in 1965 that:

Congress should promptly approve the Federal public records law now reintroduced by Senator Edward V. Long of Missouri and Representative John Moss of California. . . . The principles it involves have been extensively debated for the last decade. . . . Its great contribution to the law is its express acknowledgement that . . . citizens may resort to the courts to compel disclosure where withholding violates the [law].180

Columnist Drew Pearson used his syndicated column, “Washington Merry-Go-Round,” to attack government secrecy.181 Pearson wrote that it took a lengthy barrage of correspondence from Representative John Moss, “crusader for freedom of information,” to get the Defense Department to reveal the facts about the use of plush private airplanes by defense department officials, even to the Congress.182

Before his confrontations with the Johnson Administration, Moss had a positive relationship with President John Kennedy on the issue.183 That had led to charges that Moss was being “soft” on an administration of his own party.184 In Moss’s defense, Bruce Ladd, who worked for Rumsfeld at the time, said that Kennedy was a supporter of the principle of freedom of information and that Moss was trying to work within the administration to change the attitude of federal agencies.185 Sigma Delta Chi, the national journalism society, nonetheless charged that it was a “gentle” Moss who chided the Democratic bureaucrats over secrecy, instead of the old fire-eating Moss of 1955 to 1960, who put scores of Republican bureaucrats on the witness stand and hammered them relentlessly and publicly.186

Ladd, Rumsfeld’s staff member, wrote that the Moss critics had overlooked the subcommittee’s exhaustive hearings which had defined the secrecy problem. He thought Moss had moved to a less colorful phase of his investigation and was attempting a legislative remedy. Ladd said that Moss was able to establish a working relationship with the Kennedy administration, thus permitting “quiet persuasion” to sometimes take the place of public outcries.187

Kennedy did initiate one important change in government information policy. He gave Moss a letter—at Moss’s request—agreeing to assert executive privilege only personally and not delegate the power to lower-level officials of his administration.188 President Richard Nixon later furnished a similar pledge.189

Republican support for a freedom of information bill, fueled by Rumsfeld and then Minority Leader Gerald Ford, was new. It was something that had been decidedly absent during the Eisenhower administration. Growing press coverage made the issue better known to the public.190 The tide gradually began to turn. Moss waited, looking for a way to overcome the hesitation—or opposition—of the House leadership.191 He decided to ask the Senate to move first.192

IX. THE SENATE END RUN; EMANUEL CELLER’S GIFT

Moss’s decision to temporarily cede the leadership, of the bill he had written and an issue he had pursued for ten years, was important. With the backing of Democrat Senator Edward Long, Republican Senator Everett Dirksen and—surprisingly—even the communist-hunting Senator Joseph McCarthy, the Senate passed a bill identical to the Moss bill in October 1965.193 The House, however, still refused to act on its own committee bill. So the Senate bill was sent over to the House where it was to be assigned to a committee for consideration.194

In a stunning defeat for information advocates, it was not referred to Moss’s subcommittee. It was, instead, sent by Speaker John McCormack to the House Judiciary Committee.195 And there it languished.196

When the Senate passed the Long bill and sent it to the House, Editor and Publisher, the newspaper industry journal, observed that House members were too involved in “mending fences” to offer the public hope that anything could be accomplished to get the information bill out of the House Judiciary Committee197 Editor and Publisher added, “It might be worth a try if enough newspapers were to build a bonfire under that august body.”198

It was Moss who built the bonfire. He arranged a meeting with the chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, the dignified Emanuel Celler, of Brooklyn.199 Celler was seventy-six years old when Moss met with him in 1965.200 He had been elected to Congress from Brooklyn’s Tenth Congressional District in 1922 when he was in his mid-thirties.201

One would like to think that when John Moss came to see the powerful committee chairman, Celler remembered his own economic struggles as a young man, which were surprisingly similar to Moss’s. The position of the Democratic leadership—and President Johnson— on the Freedom of Information bill remained unclear.

Celler helped Moss. He turned jurisdiction of the Freedom of Information bill over to Moss’s subcommittee.202

Celler’s gift to Moss is almost unheard of in Congress. Ordinarily, chairmen of major committees do not turn over significant legislation to a junior member, especially one who is only the chair of a subcommittee. But somehow, Moss had persuaded Celler to give him the bill.203 Celler may have felt that Moss’s ten-year effort to get a freedom of information law through the Congress should not go unrecognized.204 Perhaps Celler wanted to get rid of a hot potato which might threaten his relations with the White House. Whatever the reason, Celler’s action proved a momentous one.

Moss constructed the bonfire that newspapers wanted to build with help from Celler, Rumsfeld, and the House Republicans.205 With jurisdiction, and at least a grudging yellow light from the House leadership, the Government Operations Committee favorably reported out the Moss information bill in May 1966.206

The fact that Moss had been willing to wait for the Senate to act and to take up the Senate bill—not a different House bill—was a key decision. It meant that there would not have to be a possibly divisive conference committee meeting between the two bodies. The bills were the same. The House bill, which was identical to the Senate bill, was reported to the full body and unanimously passed the House on June 20, 1966.207 Having passed both the House and Senate, it was sent to the White House for the president’s signature.208

X. PRESIDENTIAL VETO THREAT

The stage was now set for either the final chapter or yet another defeat for the unborn Freedom of Information Act. The bill was delivered on June 26, 1966, to President Lyndon Johnson at his Texas ranch in Johnson City on the Pedernales River.209 There it sat as the hot summer days dragged by.

Neither Moss nor Senator Edward Long knew whether Johnson would sign the bill.210 The testimony of the Department of Justice in 1965 had opined the bill was unconstitutional.211 Speaker McCormack had let Moss know that the president was displeased with the information bill and that the Executive Branch did not like it.212 Moss had moved forward against the wishes of the president.213

In June 1966, the press reported that things were looking bleak for the Freedom of Information Act.214 In an effort to reach an agreement with the White House that would get the bill signed by Johnson, Moss had met with Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach.215 He had offered a concession. Moss suggested the Department give the House some language that they would like to see in the House committee report.216 Such language, he added, might suggest a more acceptable interpretation of the parts of the legislation that the White House opposed.217 While offering to accept language in the House report, Moss stood his ground on the terms of the bill itself: “I want this bill to be passed. If counsel and the Justice Department can work out reasonable report language and my committee goes along with it, I’ll support it—with the bill as written.”218

Moss’s staff and Justice Department lawyers jointly wrote a House report.219 It was approved by the committee and released.220 It was somewhat different than the text of the legislation. The House Report suggested that Executive Branch officials would have more discretion in determining whether authorization existed for them to apply some of the bill’s exemptions, in order to deny information requests.221 Moss went along with the jointly written report, although some referred to it as a “sellout.”222 Benny Kass, Moss’s committee counsel, later said, “We believed the clear language of the law would override any negative comments in the House report. If the statute is clear, you don’t look to the legislative history.”223 More importantly, it was the price of getting a bill.224 Moss and the bill’s supporters knew they did not have the votes to override a presidential veto.225

In summary, the primary objections to the FOIA bill raised by Executive Branch agencies (including the Department of Justice, the Department of Defense, and the Civil Service Commission), incorporated the views of the White House. They included major concerns about disclosure of:

- information which could damage national defense or foreign policy interests of the U.S.;

- inter-agency or intra-agency deliberations which might inhibit government decision-making;

- personal files of individuals which should be kept private;

- information which could impair law enforcement actions of federal agencies, including the names of FBI informants;

- trade secrets and other traditionally confidential business information; and

- any other information which the president or his deputies deemed necessary to kept secret because such action was “in the public interest.”226

With significant narrowing limitations, particularly incorporating judicial review of agency denials of information requests and a shift of the burden of proof to the government to defend its denials of information requests, most of these executive branch objections were incorporated in some form into the final FOIA bill.227

Moss and his allies now waited. The bill was on Johnson’s desk in Texas. Moss was not sure whether his agreement with the Department of Justice, which resulted in the House report language, would lead to a presidential signature.228 Moss had also explained the bill to the president during at least two meetings at the White House. Whether his explanations had been convincing remained unclear.

Rather than recessing for the July 4 holiday, Congress adjourned that year.229 The adjournment was significant. Under the Constitution, if Congress is in adjournment and the president fails to sign legislation delivered to him within ten days, the bill is “pocket vetoed.”230 No Congressional vote to override is possible. Thus, if Johnson did not sign the bill by midnight July 4, 1966, it would be dead.231 The entire process would have to be repeated again, perhaps in some future Congress.

Bill Moyers, Lyndon Johnson’s press secretary at the time, had initially been skeptical of the need for a Freedom of Information Act and had sided with all federal agencies in opposition to the bill.232 But over time, noting broad press support and growing congressional support for the legislation, Moyers changed his position.233 By July 1966, he had become a supporter.

Moss told his staff to talk to the press.234 He called newspaper editors all over the country regarding the proposed law.235

XI. FOIA BECOMES LAW

On July 4, the last possible day, it appeared that Johnson would not sign the bill because of his objections to its impact on the powers of the presidency. Pressure from the press and Congress was intense.236 The issue had become political. The Republican Policy Committee had announced support for the legislation. The mid-term congressional elections were approaching in the fall. The president was focused on problems of foreign policy, mostly the growing Vietnam conflict.237 Domestic issues were no longer Johnson’s priority. At the last minute, Moyers went to Johnson’s office and recommended that he sign the bill. Johnson agreed.238

At the signing, Johnson issued a statement alluding to his deep sense of pride that the United States is an open society in which the people’s right to know is cherished and guarded.239 But Moyers, his press secretary at the time, later wrote about what had happened behind the closed doors. According to Moyers:

LBJ had to be dragged kicking and screaming to the signing ceremony. [Johnson] hated . . . of journalists rummaging in government closets; hated them challenging the official view of reality. He dug in his heels and even threatened to pocket veto the bill after it reached the White House. Only the courage and political skill of a Congressman named John Moss got the bill passed at all, and that was after a twelve-year battle against his elders in Congress who blinked every time the sun shined in the dark corridors of power. They managed to cripple the bill Moss had drafted. And even then, only some lastminute calls to LBJ from a handful of newspaper editors overcame the President’s reluctance; he signed . . . [the f—ing thing] as he called it . . . and then went out to claim credit for it.240 So the Freedom of Information Act became law.

The concerns of Moyers, that the bill had been “crippled,” and of others, that Moss had sold out, did not prove to be correct. Over the years, the courts have generally adhered to the broad principle of disclosure enunciated in the bill and have been critical of agencies attempting to withhold information.241 The exception has been in cases involving national security. It is primarily in that area, or where there is a presidential claim of executive privilege, that the law has failed to increase government information to the public.242 Executive branch delays in furnishing documents and the cost of persons and organizations going to court to retain them remain major problems and a deterrent to greater use of the Act.

The legislative struggle that was commenced by Moss in 1954 ended successfully in 1966.243 “Twas a sparkling Fourth [of July] for FoI [Freedom of Information] crusaders,” said J. Edward Murray, chairman of the American Society of Newspaper Editors’ Freedom of Information Act Committee.244 “The long campaign in the never-ending war for freedom of information was crowned by a signal triumph[,]” he said.245 “The ‘dead hero’ of the battle was the distinguished newspaper lawyer Harold L. Cross,” who wrote the basic treatise in 1953.246 The “living hero,” said Murray, “was the distinguished California Representative John E. Moss, Congress’s most inveterate FOIA champion.”247

The Freedom of Information Act has been amended several times since 1966, most recently in 2016.248 It has mostly been strengthened by Congress—particularly in 1974 and in 1996—to make the withholding of information by the federal government more difficult, to apply to electronic records, and to permit attorney’s fees to be awarded to those whose requests for government data are improperly denied.249

As Moss understood, despite the list of exemptions, the principle of openness had been firmly established. The law is used annually by as many as 700,000 “persons” (private citizens, newspaper reporters, organizations and businesses) to obtain government information.250 Moss knew the act was not perfect. “You have to make compromises,” he said.251 A decade after FOIA’s enactment, he added “If you compare it with today, we’ve made vast progress. If you ask me if we’ve made enough, the answer is no.”252

Before he died in 1997, Moss recalled that he knew from the beginning that the Freedom of Information Act would require continuing change to deal with new conditions. It would be, he predicted, a never-ending battle.253

XII. FREEDOM OF INFORMATION WORLDWIDE

The “never ending battle” for the Freedom of Information continues around the world today. According to FreedomInfo.org, today there are 117 countries with freedom of information laws, or similar administrative regulations.254 Some of the most recent to adopt such laws are Sri Lanka, Togo, and Vietnam.255

This proliferation of official legal avenues for citizens to access much of their government’s information affirms that the “right to know” is considered a universal value. While the motivations for each of the 117 countries with Freedom of Information regimes are as varied as the countries themselves, one-near constant remains: rarely have governments themselves voluntarily opened their files to their citizens; the legislation has been thrust upon them by journalists, environmentalists, historians, and anti-corruption advocates.256

The worldwide adoption of freedom of information legislation can perhaps be categorized into three waves: The Early Adopters, including Sweden (the first by 200 years), Finland in 1951, the United States in 1966 and other countries that adopted freedom of information legislation before the end of the Cold War. The Post-Cold War Openness era, including former Communist and Eastern Bloc states like Hungary and Bulgaria, but also a plethora of other countries that, when freed from the worldwide competition of capitalism and communism, were able to become more open. And finally what Thomas S. Blanton of The National Security Archive has termed “The Openness Revolution,” a period continuing from the early 1990s to the pre sent.257 This latest period has even largely overcome the closed-government backlash of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Over sixty countries including India, Mexico, and Tunisia added freedom of information laws during this period.258

In 1766, Swedish Riksdag member Anders Chydenius succeeded in establishing the world’s first freedom of information law, His Majesty’s Gracious Ordinance Relating to Freedom of Writing and of the Press.259 It opened “those recesses of knowledge” previously unavailable to the Swedish public—including the cost of pine-tar, the commodity used to seal ships, a key reason the Ordinance was drafted.260 The right to know remains built into the Swedish Constitution.261 The next freedom of information law was not passed until 1951 when Finland, still heavily influenced by its neighbor, passed a law similar to Sweden’s.262 But it was not until after John Moss’s successful endeavor in 1966 in the United States that other countries in large numbers began realizing the importance of—and enacting their own— freedom of information legislation. France passed its law in 1978.263 Between 1982 and 1983 commonwealth members Canada, Australia, and New Zealand each passed their own versions of a freedom of information law.264 Mirroring the challenges Moss faced, an Australian senator commented, upon taking governmental power in 1983, “If we are going to do anything to reform the Freedom of Information Act, and if we want to, we had better do it in the first fortnight, before the new government has any secrets to hide.”265 Of course, simply being an early adopter of freedom of information legislation, or any adopter, does not necessarily guarantee that the legislation is well-drafted or fully enforced.

The second wave of freedom of information laws came after the end of the Cold War, including—but not exclusive to—the previously communist states of eastern and central Europe. One scholar, Ivan Szekely, has written that during the communist era, Eastern Bloc countries had only “peculiar” or limited sources for transparency: samizdat, hand-copied, illegally circulated literature, and “the reimported public sphere” of western broadcast radio, including the U.S.-produced and broadcast Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty.266 But despite this restricted starting position, these previously communist countries realized the importance of open government and soon began to institute their own freedom of information laws. Among the first was Hungary, which, along with privacy protections has a constitution that, with exceptions, declares the availability of data of public interest as a fundamental right.267 Ukraine passed a freedom of information law in 1992 and enshrined the right in its constitution in 1996.268 Bulgaria and Romania have also enacted freedom of information laws, in 2000 and 2001, respectively.269 While the freedom of information laws established in post-communist countries certainly are not perfectly written or perfectly implemented, information author Ivan Szekely writes that they are having or have had the desired effect: “In all likelihood, greater transparency has complicated the lives of people holding high office, people who attempted to exploit the situation after the democratic transition, and people who tried to preserve and convert their earlier influence.”270

But the Cold War dividend did not only benefit those formerly communist countries. Other countries including Ireland (1997), Thailand (1997), and Japan (1999) also passed freedom of information laws during this wave.271 As Blanton writes, each of these three laws was also the result of a public backlash to government scandal or corruption.272 In Ireland, the most damaging scandal was a public “Anti-D” blood bank in which errors by the Blood Transfusion Service Board potentially put as many as 100,000 mothers at risk, without initially raising any alarm.273 Thailand adopted freedom of information legislation as part of a wholesale constitutional reform and enacted as a re sult of mass demonstrations against the military regime.274 In Japan, local freedom of information laws revealed the billions of yen spent on food and alcohol by Japanese government officials entertaining each other—and led to the passage of a national statute.275

Finally, the third, continuing wave of countries enacting freedom of information laws is what Blanton has termed “The Openness Revolution.”276 By 2002, there were some forty-five countries that had established some form of freedom of information legislation.277 Today, fifteen years later, that number has more than doubled to 117 countries, and shows no sign of slowing.278 The first two phases of freedom of information laws were primarily spurred from pressure from below—citizens forcing their governments to share the price of pine tar, revealing the disparate funding for different school districts, shining light on government budgets and spending, and disclosing information about ecological issues.279 During the third phase, this pressure from below is combined with pressure from above. This increased pressure from above came and comes from international institutions, such as the United Nations, which has long declared, “[f]reedom of information is a fundamental human right . . . .”280 Similarly, other institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank have concluded that better access to information makes for better markets and better standards of living.281

The U.S.-led Open Government Partnership launched in 2011 “to provide an international platform for domestic reformers committed to making their governments more open, accountable, and responsive to citizens[,]” now boasts seventy countries that have committed to work to “develop and implement ambitious open government reforms.”282

A few of the many successes from this Openness Revolution include India, Mexico, and Tunisia.283 After a decades-long fight, spurred along by multiple, diverse, grassroots efforts to end the government’s monopoly on information, India passed a freedom of information law in 2002 and a strengthened law in 2005.284 The Indian law includes a provision that Moss was unable to build into the American FOIA: an Information Commission which (in theory) is the final arbiter responsible for adjudicating disputes between citizens and the government.285 According to one Indian FOI expert, Shekhar Singh, “perhaps not since the concept of democracy itself was first conceived has any idea so caught the imagination of the people of India and so promised to revolutionize the way they will allow themselves to be governed.”286

Mexico passed its freedom of information law in 2002.287 In 2006, the Mexican Constitution was reformed to establish minimum standards of disclosure at the federal, state, and municipal levels. The law established a website called “Infomex,” which users can use to send requests, appeal agency decisions, and consult every request and public response ever processed electronically.288 According to the website Freedominfo.org, “this type of electronic filing system gives citizens the ability to view the progress and trajectory of Mexico’s transparency over time, and represents one of the most advanced Webbased information portals in the world.”289 The Mexican freedom of information law also surpasses the U.S. in another key provision that, at least in theory, forbids hiding or denying information related to gross human rights violations.290

After establishing itself as perhaps the only successful political revolution of the Arab Spring, Tunisia further solidified its fledgling democracy by passing its own freedom of information law in 2016.291 According to Kouloud Dawahi, the Tunisian law is based upon published consensus international norms, and succeeded in part because Tunisia made a public commitment to be admitted into the international Open Government Partnership.292 Again, this young law surpasses the American FOIA in one significant way, requiring the law to apply to both Tunisia’s central and local governments, each of the its three branches (executive, legislative, and judiciary), and to other relevant bodies, including public enterprises and regulatory authorities.293

The international movement toward freedom of information laws, spurred in part by the American Freedom of Information Act and its author John Moss, is nothing short of remarkable.

XIII. INTERNATIONAL AND AMERICAN CHALLENGES

At a recent U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee Hearing commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the U.S. Freedom of Information Act, Senator Al Franken (D-MN) took issue with a survey showing that on paper, Russia had a stronger freedom of information law than the United States.294 “I can’t believe that,” Franken said.295 He had an important point; in one year alone the U.S. Freedom of Information law led to major revelations about Pentagon officials misleading Con gress on the Department of Defense’s handling of sexual assault cases, the EPA and state decisions that led to lead poisoning of children in Flint, Michigan, widespread overcharging in Medicare, cheese marked as being “100% parmesan” actually containing no parmesan, and hundreds more.296 That is an important yardstick for other governments because the disclosures directly challenged important executive actions and functions.

But merely because information requests can win the release of documents from their governments does not mean that the laws and their implementation do not need to be improved. Of the 117 freedom of information laws that exist, many that appear strong on paper are actually weak in practice. Public servants are often ignorant of, or outright hostile to such laws. Judges and ombuds offices are often overly deferential to their colleagues in governments. Threshold issues, including poor record keeping, destruction of documents, and lack of resources, all too often make requested records difficult or impossible for the public to find. Unacceptably long delays are all too common. For instance, in the United States, the National Security Archive has some FOIA requests that have been pending for two decades.297

However, there is progress as well. Countries, including many cited in this paper, have proven that such obstacles can be overcome. Perhaps the best way to measure and improve international openness is for countries to legislate, and to ensure that they actually facilitate the “Five Fundamentals” of openness. As Blanton has written: [O]penness advocates have reached consensus on the five fundamentals of effective freedom of information statutes:

* First, such statutes begin with the presumption of openness. In other words, information is not owned by the state; it belongs to the citizens.

* Second, any exceptions to the presumption must be as narrow as possible and written in statute, not subject to bureaucratic variation and the change of administrations.

* Third, any exceptions to release must be based on identifiable harm to specific state interests, not general categories like “national security” or “foreign relations.”

* Fourth, even where there is identifiable harm, the harm must outweigh the public interest served by releasing the information, such as the general public interest in open and accountable government, and the specific public interest in exposing waste, fraud, abuse, criminal activity, and so forth.

* Fifth, a court, an information commissioner, an ombudsperson or other authority that is independent of the original bureaucracy holding the information should resolve any dispute over access.298

Beyond these fundamentals, it is now increasingly clear that, in the information age, a “sixth fundamental” is required for freedom of information laws.299 This policy requires that governments make their information widely available to and easily usable by the public.300 Documents likely to be requested under freedom of information laws should be proactively posted online; releases to requesters— processed with taxpayer funds—should also be made digitally available to the widest possible audience, not shipped in a package and possibly lost forever in a desk drawer.301

Even after the passage of the 2016 FOIA Improvement Act,302 (creating a requirement of reasonably foreseeable harm to a protected interest, if a request for government information is denied) an honest appraisal of the American law shows that often in practice—if not in text—it does not fulfill all of the six principles of openness. In a study of one recent year, up to sixty percent of all American FOIA requests were withheld in whole or in part.303 The government’s FOIA exemptions remain very broad and easy to apply;304 years and decade-long delays often effectively deny requesters the information they need,305 and fees are often used to deter people from making requests (even though they cover just one percent of all government FOIA costs).306 The Department of Justice (which implements FOIA), the FOIA Ombuds Office, and the federal courts all too often provide unqualified support to agency withholdings.307

But as FOIA’s author, Representative John Moss knew all too well, this reality should not be surprising. Despite the “vast progress”308 made in the United States and internationally, there is always much more to be done to ensure that citizens have full access to their information.

† This article was revised from a paper submitted to “Freedom of Information Laws on the Global Stage: Past, Present and Future,” a symposium held at Southwestern Law School on Friday, November 4, 2016. The Symposium was organized by Professor Michael M. Epstein and Professor David Goldberg and jointly by Southwestern’s Journal of International Media and Entertainment Law and Journal of International Law. Portions of this article discussing Congressman John Moss and the passage of the U.S. Freedom of Information Act were taken from co-author Michael R. Lemov’s book People’s Warrior, John Moss and the Fight for Freedom of Information and Consumer Rights (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press/Rowman and Littlefield, 2011).

* Michael R. Lemov is an attorney and former Commerce Committee counsel for Congressman John Moss. He is the author of People’s Warrior, John Moss and the Fight for Freedom of Information and Consumer Rights (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press/Rowman and Littlefield, 2011).

** Nate Jones is the Director of the Freedom of Information Act Project for the National Security Archive. He is also a Cold War historian and frequently utilizes FOIA in his research. He is the author of Able Archer 83: The Secret History of the NATO Exercise That Almost Triggered Nuclear War (The New Press, 2016).

- Interview by Donald B. Seney with John E. Moss, Congressman, U.S. House of Representatives, in Sacramento, Cal., 15 (Oct. 3, 1989) [hereinafter Interview by Seney with Moss], http://archives.cdn.sos.ca.gov/oral-history/pdf/oh-moss-john.pdf.

- Id. at 19.

- Fast Facts: Freedom of Information Laws Around the World, RAPPLER (July 23, 2014, 9:15 AM), https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/63867-fast-facts-access-to-information-lawsworld.

- C.J. Ciaramella, The Freedom of Information Act—and the Hero Who Pioneered It, PACIFIC STANDARD (June 29, 2016), https://psmag.com/news/the-freedom-of-information-act-andthe-hero-who-pioneered-it.

- Id.

- See Chronological and Alphabetical Lists of Countries with FOI Regimes, FREEDOMINFO.ORG (Sept. 28, 2017) [hereinafter List of Countries with FOI Regimes], http:// www.freedominfo.org/?p=18223.

- MICHAEL J. HOGAN, A CROSS OF IRON 315 (1998).

- Id.

- $4 Million For Probes, 9 CONG. Q. ALMANAC 69 (1953).

- See HOGAN, supra note 7, at 254 (citing Exec. Order No. 9,835, 3 C.F.R. Supp. 2 (1947)).

- See Exec. Order No. 9,835, 3 C.F.R. Supp. 2 (1947); HOGAN, supra note 7, at 254.

- See Exec. Order No. 9,835, 3 C.F.R. Supp. 2 (1947); HOGAN, supra note 7, at 254.

- See HOGAN, supra note 7, at 255.

- Bailey v. Richardson, 182 F.2d 46, 66 (D.C. Cir. 1950) (Edgerton, J., dissenting).

- Id. at 74.

- Id.

- Id. at 65-66.

- Bailey v. Richardson, 341 U.S. 918, 918 (1951).

- See Interview by Seney with Moss, supra note 1, at 19.

- See MICHAEL SCHUDSON, THE RISE OF THE RIGHT TO KNOW 39 (2015).

- See MICHAEL R. LEMOV, PEOPLE’S WARRIOR: JOHN MOSS AND THE FIGHT FOR FREEDOM OF INFORMATION AND CONSUMER RIGHTS 43 (2011). See generally Interview by Seney with Congressman Moss, supra note 1.

- LEMOV, supra note 21(citing author’s 1996 interview with John E. Moss).

- See Interview by Seney with Moss, supra note 1, at iii.

- See id. at 62-63.

- See id. at iii.

- See id. at 10.

- See LEMOV, supra note 21, at 44 (citing author’s 1996 interview with John E. Moss).

- Id.

- See SCHUDSON, supra note 20.

- See Kathy Gill, What is the Seniority System? How Power is Amassed in Congress, THOUGHTCO., https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-the-seniority-system-3368073 (last updated Dec. 26, 2016).

- See Postal Rates, Postal Pay Hikes, CONG. Q. ALMANAC 1954, 10TH ED., 1955, goo.gl/ Vc9XQZ (follow “Postal Rates, Postal Pay Hikes – CQ Almanac Online Edition” hyperlink) (indicating that, in 1954, Congressman Moss supported HR 9836 and HR 6052, which sought to, respectively, increase mail rates and increase the pay of postal employees).

- See H.R. Journal, 82nd Cong., 2d Sess. 720-21 (1951-52) (indicating a change in the name of the “Committee on Expenditures in the Executive Departments” to the “Committee on Government Operations” on July 3, 1952 via unanimous consent following House Resolution 647); H.R. Journal, 90th Cong., 2d Sess. 1315 (1968) (outlining the powers and duties of the Committee on Government Operations, which include, among others, “receiving and examining reports of the Comptroller General of the United States [i.e. the director of the Government Accountability Office] and of submitting such recommendations to the House as it deems necessary or desirable in connection with the subject matter of such reports; . . . studying the operation of Government activities at all levels with a view to determining its economy and efficiency . . . .”).

- See 2 GARRISON NELSON ET AL., COMMITTEES IN THE U.S. CONGRESS 1947-1992, at 643 (1994).

- See LEMOV, supra note 21, at 45-46.

- See id. at 46.

- See id.

- See Interview by Seney with Moss, supra note 1, at iii.

- See LEMOV, supra note 21, at 46.

- Id.

- Id.

- Id.

- See Interview by Seney with Moss, supra note 1, at iii, 139.

- See LEMOV, supra note 21, at 46.

- Interview by Seney with Moss, supra note 1, at 149.

- See BERRY JONES, DICTIONARY OF WORLD BIOGRAPHY 710 (4th ed. 2017) (indicating that Rayburn was a U.S. Congressman from 1913 until 1961); SCHUDSON, supra note 20, at 147 (indicating that in the 1940s and 1950s Congressman and then Speaker Rayburn was a powerful figure); Deward C. Brown, The Same Rayburn Papers: A Preliminary Investigation, 35 THE AM. ARCHIVIST 331, 331 (1972) (indicating that Rayburn became Speaker in 1940 and acted as the Chairman of the Democratic National Convention in 1948, 1952, and 1956); Interview by Seney with Moss, supra note 1, at iii (indicating that Moss was born in 1913, the same year Rayburn was first elected, and that Moss was elected to Congress as a Representative of the Third District in 1952).

- See Interview by Philip M. Stern with John Moss, U.S. House of Representatives, in Wash. D.C. (Apr. 13, 1965). Moss did not seek to continue as deputy floor whip after his confrontation with the White House and the House leadership over the Freedom of Information Act in the early 1960s. He said he wanted to pursue his own agenda and that he was not forced to resign.

- See SCHUDSON, supra note 20, at 40.

- LEMOV, supra note 21, at 46.

- See SCHUDSON, supra note 20, at 46; Harold C. Relyea, Freedom of Information, Privacy, and Official Secrecy: The Evolution of Federal Government Information Policy Concepts, 7 SOC. INDICATORS RES. 137, 138-39 (1980).

- SCHUDSON, supra note 20, at 42. See generally Exec. Order No. 9,835, 3 C.F.R. Supp. 2 (1947) (the executive order that began the “Loyalty Program”); Deward, supra note 45, at 336 (pointing out the anti-communist hysteria that existed during the 1950s).

- BRUCE LADD, CRISIS IN CREDIBILITY 188 (1968).

- Id. at 188-89; Bruce Ladd, 50 Years After FOI Act, Celebrating Government Transparency, THE NEWS & OBSERVER (July 3, 2016), http://www.newsobserver.com/opinion/op-ed/ article87239527.html.

- See SCHUDSON, supra note 20, at 45-46.

- LADD, supra note 51, at 189.

- Id.

- Id.

- Id.

- Id. at 189-90.

- HERBERT N. FOERSTEL, FREEDOM OF INFORMATION AND THE RIGHT TO KNOW 15 (1999).

- KENT COOPER, THE RIGHT TO KNOW xii (1956).

- Id. at xiii.

- SCHUDSON, supra note 20, at 42.

- FOERSTEL, supra note 59, at 16.

- Id. at 17.

- Id. at 17.

- See HAROLD L. CROSS, THE PEOPLE’S RIGHT TO KNOW xiii, 49-50 (1953).

- Id. at xiii.

- See id. at 48, 58.

- Id. at 197.

- See id. at 23, 198-99.

- SCHUDSON, supra note 20, at 42.

- CROSS, supra note 66, at 132.

- See Albert G. Pickerell, Secrecy and the Access to Administrative Records, 44 CAL. L. REV. 305, 306-08 (1956).

- SCHUDSON, supra note 20, at 40.

- FOERSTEL, supra note 59, at 18-19.

- Id. at 19.