The Pinochet Regime at 50

Washington, D.C., October 1, 2024 - On the 50th anniversary of the Pinochet regime’s first act of international terrorism, the National Security Archive is posting a compilation of documents, including CIA intelligence reports and a judicial confession of the Chilean secret police operative, Michael Townley, who constructed, placed, and detonated the car bomb that killed Chilean General Carlos Prats and his wife Sofía Cuthbert in Buenos Aires on September 30, 1974.

Only weeks after the bombing, a friend of the Prats daughters gave them a chilling message: the Pinochet regime planned to “celebrate the coup” every September by eliminating specific persons deemed a threat to the dictatorship. This information proved to be prescient. The following September, the Vice President of the Chilean Christian Democrat Party, Bernardo Leighton, and his wife were gunned down and critically injured on a street in Rome. A year later, on September 21, 1976, a car bomb similar to the one that killed the Prats took the lives of former Chilean ambassador Orlando Letelier and his young colleague Ronni Karpen Moffitt in Washington, D.C.

“The first [assassination] was our parents,” Sofía, Angélica and Cecilia Prats write in their new book, Lo que tarde la justicia, published in Chile this week.

The compilation of records posted today marks an anniversary that was commemorated in Buenos Aires, where the attack took place, as well as in Chile, where the atrocities of the Pinochet era continue to cast a shadow over present-day politics. “The Prats case,” notes Archive Senior Analyst Peter Kornbluh, “provides a dramatic reminder of the true terrorist nature of the military dictatorship—and of Pinochet himself.”

Targeting General Prats

The target of the Pinochet regime’s first act of international terrorism was not a renowned leftist or socialist militant but rather Pinochet’s own predecessor as Commander-in-Chief of the Chilean Army, General Carlos Prats González. A pro-constitution officer, General Prats assumed the top military position in Chile in October 1970, after his own predecessor, General René Schneider, was assassinated in a CIA-supported plot to block the inauguration of president-elect Salvador Allende.

During Allende’s tumultuous three years, Prats used his powerful position to safeguard Chile’s constitutional order. In 1972, he entered Allende’s cabinet and even held the position of vice president of the nation. In June 1973, he quickly suppressed a coup attempt—known as the “Tanquetazo”—by junior officers and the extremist paramilitary group, Patria y Libertad. In late August 1973, however, protests against Prats’ continuing support for the Allende government forced him to resign. Prats personally recommended General Augusto Pinochet to replace him as commander-in-chief, erroneously believing that he would support the constitutional order against pro-coup officers.

Only four days after the coup, General Prats and his wife went into exile in Argentina. Prats “was living quietly in Buenos Aires,” the CIA later reported. “He was not permitted to make any public appearances or statements and had faithfully carried out the restrictive instructions pertaining to his exile.”

But General Pinochet clearly considered the highly respected Prats to be a potential threat to his power. Only six weeks after the coup, Pinochet dispatched one of his top deputies, General Sergio Arellano Stark, to Buenos Aires to conduct secret talks with the Argentine military. Arellano’s top priority, according to a CIA source, was to “discuss with the Argentine military any information they have regarding the activities of General (retired) Carlos Prats. Arellano will also attempt to gain an agreement whereby the Argentines maintain scrutiny over Prats and regularly inform the Chileans of his activities.” In June 1974, Pinochet met with the director of the Chilean secret police, DINA, Colonel Manuel Contreras, and ordered him to eliminate Prats.

Contreras first assigned this mission to his DINA station chief in Argentina, Enrique Arancibia Clavel, who was instructed to enlist Argentine paramilitary groups to kill Prats. When that effort failed to advance, DINA’s deputy director, Colonel Pedro Espinoza, enlisted DINA’s newest recruit, an American expatriate named Michael Townley who was an electronics specialist and had collaborated with Patria y Libertad in anti-Allende operations.

In secret testimony given to an Argentine judge in 1999, Townley recalled how Colonel Espinoza had described Prats as a potential leader of a government-in-exile and asked Townley if he could “do something” about the exiled general. Eliminating Prats “was for the wellbeing of the country,” Townley testified. “It was a patriotic request,” he stated. “So, I did it.”

Townley traveled to Buenos Aires twice; the first time he was unable to locate Prats. Accompanied by his wife Mariana Callejas—also a DINA agent—he returned on September 10, 1974, and spent several weeks plotting the assassination. At one point, Townley followed Prats into a neighborhood park and considered shooting him in broad daylight, but, he testified, “there were too many people around.” Instead, Townley fashioned a remote-controlled car bomb made of two C4 cartridges, establishing his signature modus operandi as an international terrorist. On September 29, he managed to slip into the parking garage and attach the device to the chassis of Prats’ small Fiat 125. Townley and Callejas then staked out the Prats’ building until they returned from visiting friends just after midnight on September 30. Callejas tried to detonate the bomb, “but it did not function,” Townley confessed. “I took [the detonator] from her, pressed it, and it worked.”

The Pursuit of Justice

For over thirty years, the Prats family pursued efforts to identify the perpetrators of this atrocity and prosecute them. In 1983, two daughters, Sofía and Angélica Prats, traveled to Washington, D.C., to work with Argentine lawyers requesting the extradition of Townley—then under witness protection in the United States after serving a short sentence for assassinating Orlando Letelier and Ronni Moffitt with a car bomb—to Buenos Aires. But a U.S. judge ruled that Townley’s plea bargain agreement in the Letelier-Moffitt case prevented his extradition. A Chilean judge also denied Argentine legal efforts to have Mariana Callejas extradited from Santiago to Buenos Aires to stand trial. In 1987, the Prats daughters repeatedly approached the U.S. Embassy in Chile seeking information and legal assistance in the case. Eventually, their efforts led an Argentine judge, Maria Servini, to travel to Washington in 1999 and officially depose Townley. For a number of years, his secret testimony remained sealed. (See Document 8)

“We instinctively understood that the search for justice would be a lengthy journey,” Sofía, Angélica and Cecilia Prats write in their new book. “We knew it would be arduous, beginning with a period of mourning that would last an unknown amount of time.”

Argentine authorities did eventually arrest DINA agent Enrique Arancibia Clavel, charging him first with espionage and then as an accessory to the Prats assassination. He was imprisoned in Argentina for almost two decades.

More than 35 years after Prats and Cuthbert were assassinated, and 20 years after the return to civilian governance, in June 2010 the Chilean courts finally convicted and sentenced former DINA chief Manuel Contreras and his deputy Pedro Espinoza, along with several other DINA officials and operatives in the Prats case.

Pinochet himself was never prosecuted for the Prats assassination, nor for the other acts of terrorism he ordered. After he died on December 10, 2006—ironically, international Human Rights Day—the Chilean military arranged for his open coffin to be viewed by his admirers. Francisco Cuadrado Prats, the grandson of Carlos and Sofía Prats, stood in the viewing line with hundreds of Pinochetistas; when he reached the coffin, he spat on the glass covering Pinochet’s face. “It was a spontaneous act to spit on him out of revulsion,” the young Prats recalled after he was beaten by Pinochet supporters and then arrested for his sacrilegious conduct, “because he had my grandparents murdered.”

The Documents

Document 1

Clinton Chile Declassification Project

Only six weeks after the coup, General Pinochet dispatched one of his top deputies, General Sergio Arellano Stark, to Buenos Aires to conduct secret talks with the Argentine military. Arellano’s top priority, according to a CIA source, is to “discuss with the Argentine military any information they have regarding the activities of General (retired) Carlos Prats. Arellano will also attempt to gain an agreement whereby the Argentines maintain scrutiny over Prats and regularly inform the Chileans of his activities.” Instigated by “the Junta leadership,” according to the cable, this “special mission” provides the first evidence of Pinochet’s direct role in the Prats assassination case.

Document 2

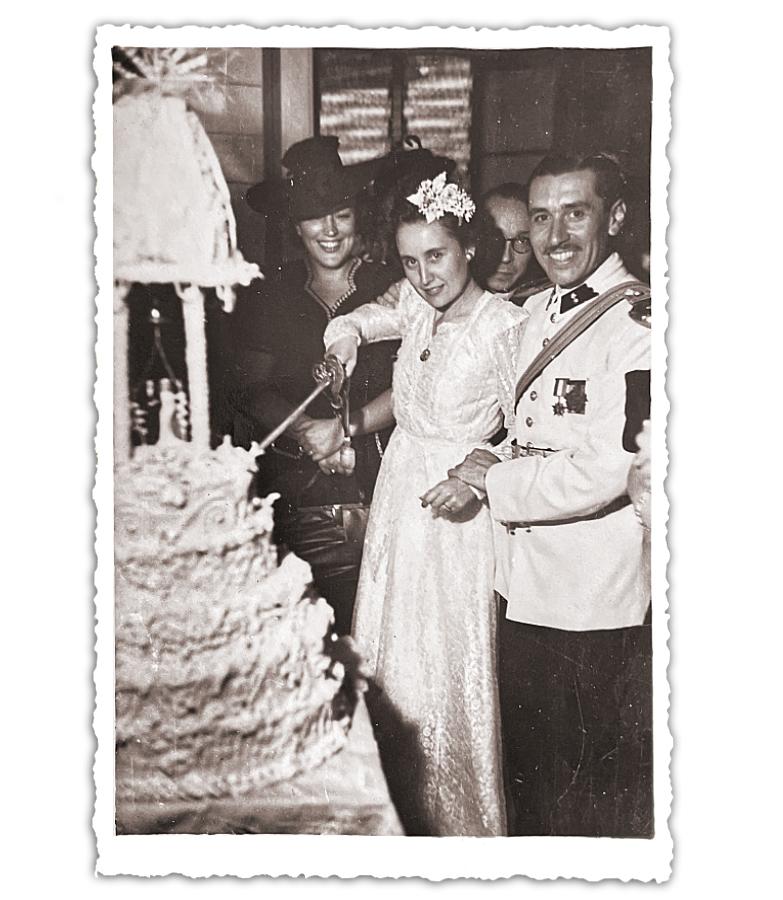

Prats family archives

In June 1974, following a reported meeting in which General Pinochet ordered the elimination of General Prats, DINA director Manuel Contreras dispatched an operative to conduct surveillance on the movements of General Prats in Buenos Aires. In this rare DINA cable, Captain Juan Morales files an intelligence report that provides Prats’ addresses for home and work, as well as the workplace of his wife, Sofia Cuthbert. The surveillance report describes the models of the cars used by the Prats couple, provides an account of his movements, and notes the lack of security personnel to protect him. Morales also provides a hand-drawn diagram of the street and entrance to the Prats’ parking garage.

Document 3

Prats family archives

In this communication between the Chilean consulate in Buenos Aires and the Chilean Foreign Ministry, Consul Álvaro Droguett requests guidance on whether to provide General Prats and his wife Chilean passports so they can travel to Brazil. The response he receives only four days before the assassination is that it would be “inconvenient” to provide the passports to the Prats couple. After the Prats family demands a copy of the denial, Droguett provides them with a Xerox copy of his letter with a handwritten note at the bottom quoting the Ministry’s response and claiming that he only became aware of the denial on September 30th—the day of the assassination.

Document 4

Clinton Chile Declassification Project

The CIA includes an initial report on the Prats assassination in its weekly summary of international terrorism. Their initial description cites erroneous police reports that the Prats were “killed by the blast of a bomb thrown at their car” along with machine gun fire as they returned to their home. The report accurately states that “the assassins were waiting for Prats and his wife as he drove up to his apartment building.” Further investigation soon revealed that the bomb had planted under the Prats’ Fiat 125 and later detonated by the assassins—DINA agents Michael Townley and his wife Mariana Callejas—who were waiting in a car across the street for the Prats to return.

Document 5

Clinton Chile Declassification Project

Reacting to press reports that point the finger of responsibility at the Chilean secret police, the U.S. Embassy reveals how detached it is from the ruthless reality of Pinochet’s repression. Ambassador David Popper dismisses a Radio Moscow report that DINA had assassinated General Prats “on basis of rationale that Chilean military leaders were afraid Prats would attract loyalty of Chilean armed forces personnel disaffected with performance of Junta.” “This explanation makes no sense to us,” Ambassador Popper reported. Nor do we see significant interest in killing Prats of any other Chilean group with capacity of doing so.”

Document 6

Clinton Chile Declassification Project

Almost a month after the Prats assassination, the CIA station files a report providing important details from official and confidential sources. The intelligence brief states that “official Argentine government circles consider the assassination of General Prats to be the work of Chileans,” although they are not sure “whether the assassination was the work of a Chilean left-wing or right-wing group.” The report reveals that Prats had received “a phone call from a Chilean attempting to assume an Argentine accent” warning that his life was in danger and urging him to leave the country. The CIA concluded the cable by citing a possible motivation for the assassination. “Prats had nearly completed his memoirs which strongly condemned many non-Popular Unity politicians and military officers” for their roles in the coup.

Document 7

Clinton Chile Declassification Project

In a visit to the U.S. Embassy in Santiago, the daughters of Carlos Prats and Sofía Cuthbert press their efforts to hold the murderers of their parents accountable. A top DINA officer, Armando Fernández Larios, who participated in the car bomb assassination of Orlando Letelier and Ronni Moffitt, has recently turned himself in to U.S. officials, and the daughters seek to have him questioned in the Prats case. They also inform the Chargé that the Argentine courts are seeking the testimony of Chilean officers, but that the military regime has refused to cooperate. In this cable to Washington, Ambassador Harry Barnes requests information on whether the Argentine courts have the legal latitude to formally interrogate Michael Townley, who has finished his short incarceration for the Letelier-Moffitt assassination and is living in the United States under the witness protection program.

Document 8

U.S. Federal District Court

As part of Argentina’s legal effort to prosecute the perpetrators of the Prats’ murders in Buenos Aires, the DINA operative who planted and detonated the car bomb, Michael Townley, was officially interrogated by Argentine Judge Maria Servini in Washington, D.C., with the assistance of U.S. Justice Department attorney, John Beasley, Jr. In his sworn testimony, Townley recalled how a top DINA officer, Colonel Pedro Espinoza, had repeatedly approached him in late July and August 1974 about “doing something” about General Prats, who Espinoza described as a potential leader of a government-in-exile. Eliminating Prats “was for the wellbeing of the country,” Townley testified. “It was a patriotic request,” he stated. “So, I did it.”

Townley described two trips to Buenos Aires in September 1974; during the first trip, he was unable to locate Prat’s address; during the second trip, another DINA officer provided him with the location of the apartment building at Malabia 3351. He described how he managed to sneak into the parking garage and attach the bomb he had assembled with two sticks of C4 explosives and an electronically activated detonator to the undercarriage of Prats’ Fiat. Although Townley repeatedly attempted to convince Judge Servini that he had acted alone in the bombing, under intense questioning he was forced to admit that his wife, Mariana Callejas, had accompanied him to Buenos Aires and participated in the mission. “She tried to detonate the bomb, but it did not function,” Townley confessed. “I took [the detonator] from her, pressed it, and it worked.”