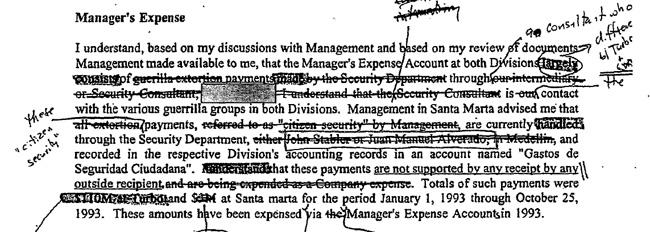

The FARC, the ELN, and to a lesser extent, the EPL, along with their dissident offshoots and political allies all profited from Chiquita’s security payments. Newly declassified documents on this little-known episode in the violent history of Colombia’s banana-growing zone shine a spotlight on the sometimes- blurry line between paying extortion, making contributions, and the deliberately financing of violent actors. The Special Jurisdiction for Peace, a tribunal established as part of peace accord with the FARC, will have the final word.

Ten years have passed since Chiquita Brands was sentenced in the United States for financing an international terrorist group. In 2007, the company confessed to paying the paramilitary United Self-defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) and also admitted that between 1989 and 1997 it funded the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN), the country’s two largest rebel groups.

But unlike payments to the AUC, Chiquita’s financial ties to guerrilla groups were not a concern of U.S. courts. The FARC and the ELN had not yet been declared foreign terrorist organizations by the U.S. when those payments were made; and while both groups were so designated in October 1997, the court found no evidence that the company had paid either of them beyond that date.

In Colombia, the Justice and Peace tribunals have documented how money that banana companies gave to private security cooperatives known as Convivir ended up in the coffers of the right-wing AUC. But until now there has been little evidence of how cash from the fruit multinational made its way into the hands of leftist Colombian guerrilla groups.

These kinds of records are all the more important now, following a December 2016 ruling by the Colombian Attorney General that the voluntary financing of paramilitary groups by banana companies is a crime against humanity, and that payments to guerrillas from the FARC, the People’s Liberation Army (EPL), the ELN and the Socialist Renovation Current (CRS) are to be treated in the same manner. The ruling means that the crimes are still actionable in Colombian courts despite the passage of time and that the Colombian justice system must fully investigate the violations to punish those responsible.

As these processes get underway, a new batch of declassified documents obtained under the U.S. Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) by the National Security Archive provides a detailed accounting of the payments that Chiquita Brands and three other banana companies made to Colombian insurgent groups between 1989 and 1997. The records for the first time reveal the minimum amounts of money Chiquita paid to the various Colombian guerrilla groups, and provide a unique, first-hand account of the harrowing and complicated security situation in Urabá from the practical and calculated perspective of one of the world’s biggest fruit companies.

How much money went to the Guerrillas?

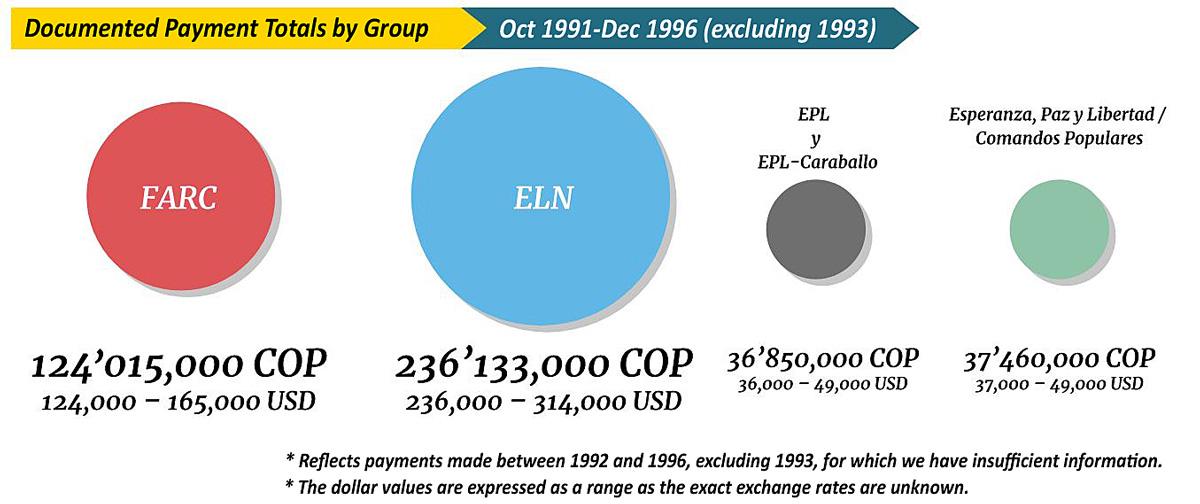

Based on the documentation provided to U.S. authorities by Chiquita and subsequently obtained through FOIA requests, it is possible to document payments from Chiquita to Colombian guerrilla groups of an estimated $856,815 in a little more than five years, from October 1991 through 1996. These totals do not include any money transferred to guerrillas before October 1991 or after 1996. Payments are said to have begun in the late-1980s and continued through part of 1997.

Source documents for above information: 19920904; 19930311; 19950516; 19950616; and 19950000.

The U.S. dollar amounts shown above reflect a range of possible exchange rates for those years, which are not specified in the underlying documentation. The upper end of this range brings us closer to the estimated grand total of $856,815 for all guerrilla payments, most of which was found expressed in true dollar amounts in the auditing records.

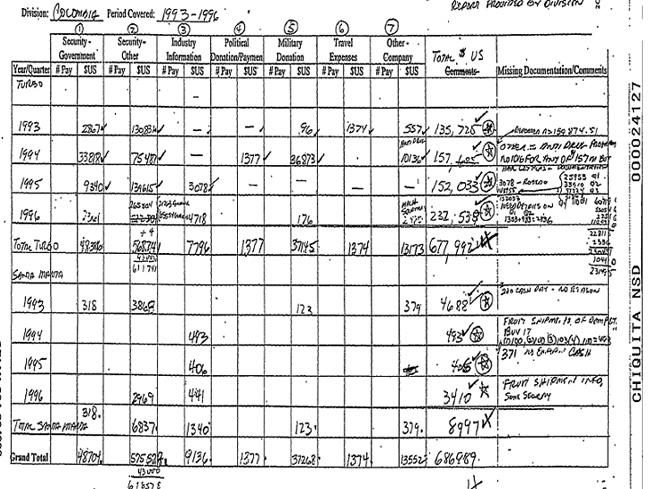

That figure covers all payments from 1992-1996 and draws on information found in two key records laying out payment totals for different periods of time.

- One is an internal auditing worksheet reporting an exact total of $618,578 paid from 1993-1996.

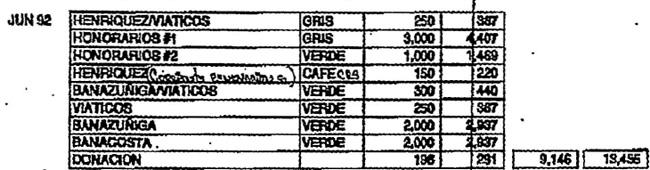

- For 1992, the clearest evidence comes from an internal security report with payments totaling some 129,979,000 Colombian Pesos for that year (estimated to be around $260,000 at an approximate 1992 exchange rate of 500:1).

- We have also taken care to subtract $21,763 from that total, the amount paid to Convivir groups in 1996. These are the first known payments to the controversial self-defense organizations that collected money from Chiquita on behalf of anti-guerrilla paramilitary groups. Information about these early Convivir payments is drawn from an annotated general ledger found among the Chiquita Papers.

There are some additional caveats. The collection does not include detailed information about payments made in 1993. As a result, while we know the total amount of all guerrilla-related payments made that year, we do not have information about the specific amounts paid to each group. Rather than estimate those amounts, we have simply left them out of the per group totals. These caveats mean that the totals shown above, and the numbers for at least some, if not all, of the groups are likely too low, in some cases by significant amounts. The auditing worksheet from 1997 records more than $134,000 in guerrilla payments (listed here under “Security-Other”) for 1993—money that is not accounted for in the per group totals above.

Banadex, Chiquita’s main subsidiary in Colombia, played a fundamental role in this scenario. At the beginning of the 1990s the banana sector was a vital part of the Colombian national economy. The coffee crisis of the previous decade and the expansion of the international market turned bananas into the country’s primary agricultural export.

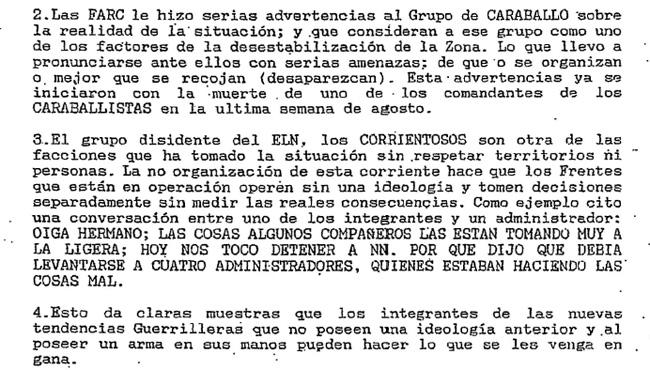

At the time, this vital region was home to two primary guerrilla organizations, each with strong ties to banana industry trade unions: the FARC and the EPL. When the latter demobilized in 1991, two groups emerged: a dissident EPL faction under Francisco Caraballo that refused to lay down its weapons and a new political movement that went by the same initials, Esperanza, Paz y Libertad (Hope, Peace and Liberty). In the face of attacks by the FARC and the Caraballo group against the “Esperanzados,” who were viewed as traitors by the remaining guerrilla factions, some of the demobilized decided to rearm themselves and create the Comandos Populares (Popular Commands), a group that later merged with paramilitary AUC.

Although the ELN did not maintain a strong presence in the zone, the country’s second-largest rebel group also showed up in the accounts of the banana companies, along with a group of dissidents from the CRS whose members signed a peace accord with the government on April 9, 1994. The end of the 1980s also saw the sporadic emergence of the first paramilitary groups in the region.

Between 1989 and 1997, when the guerrilla payments were made, there were 54 massacres in the banana zone municipalities of Apartadó, Carepa and Turbo, according to information from the Observatory of Conflict and Memory of the National Center of Historical Memory in Colombia. The guerrillas assassinated 181 individuals in 21 of these massacres. Fifteen of these were the work of the FARC.

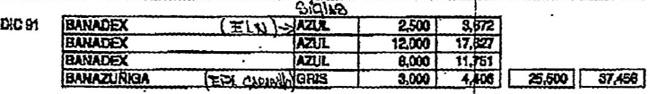

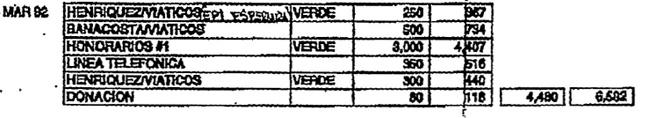

Chiquita’s internal documents show the company funded all of these armed groups, dissidents and political movements, but in amounts that varied depending on the terms negotiated with each organization. In accounting records the company used color code names to record the destination of the payments without mentioning the names of the recipient guerrilla groups. In underlying documentation, company officials often used fictitious, misleading or euphemistic descriptions for the payments to subversive organizations, such as “chopped wood,” “gasoline,” or “boys in the hills.”

To conceal the payments, Chiquita invented an accounting system that we described in the second article in this series.

The guerrilla payments were consigned to the so-called “Citizen Security Account” and were made primarily through Banadex and the Compañía Frutera de Sevilla, Chiquita’s two main Colombian subsidiaries, but some payments also were made by way of the multinational’s Colombian partners, like Banazuñiga y Banacosta. There are also outlays registered under the name “Henríquez,” a possible reference to the Henríquez Gallo family, which was heavily invested in the banana plantations in Urabá. In 2014, two members of the Henríquez clan, Jaime and his brother Guillermo, were identified as paramilitary financiers by former AUC chiefs Raúl Hasbún and Freddy Rendón Herrera.

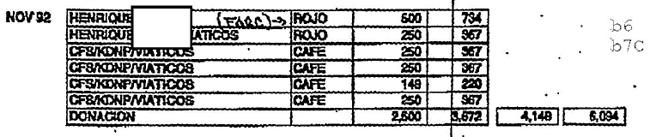

In January 2000, as part of secret testimony before the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), Robert F. Kistinger, a top Chiquita executive in Cincinnati, insisted that the company was being extorted by guerrillas. Nevertheless, drafts of confidential internal memoranda show that company officials did not want to characterize the payments as extortion, instead suggesting the term “citizen security payments,” as seen in the following record.

Neither did the company denounce the extortion attempts or inform the Colombian government that it was being threatened by guerrillas. VerdadAbieta.com has learned that the Attorney General’s office recorded only one complaint made by Chiquita to Colombian authorities, and only in reference to paramilitary groups.

According to Mario Agudelo, a former EPL guerrilla who went on to lead the Esperanza political movement and who knows well the history of Urabá, “in the case of the ‘paras’ and the FARC there was permanent financing.” This was distinct, in his view, from the sporadic payments that were made to other armed groups in the zone. “To what extent was this the result of armed pressure? I’m in no position to say in which case yes and in which case no, but what is tangible is that they provided support and this was the result of a long-term agreement.”

The basic situation was well-understood by actors in the zone at that time. Carlos Alfonso Velásquez, a former Colombian Army colonel assigned to the 17th Brigade in Urabá in the mid-1990s, remembers hearing similar things from his commanding officer, Gen. Víctor Álvarez: “I was told one day, ‘those bananeros, those ranchers, they come here to ask for support, that the guerrillas are threatening them, that they are being extorted by them, but I know that they give them money under the table.”

Negotiating with the ELN

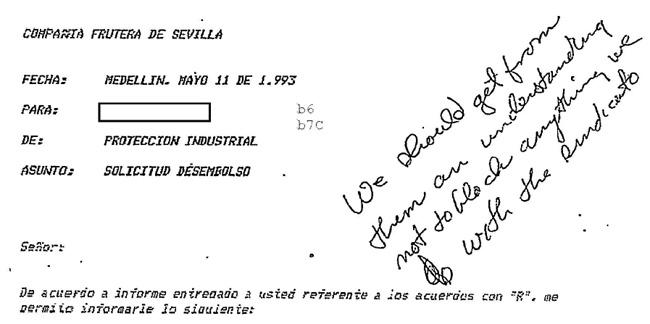

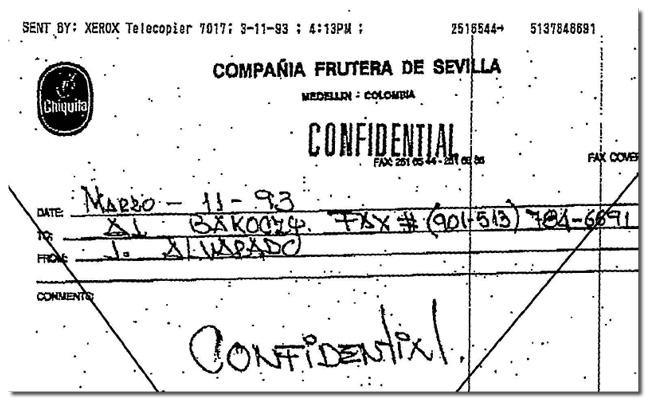

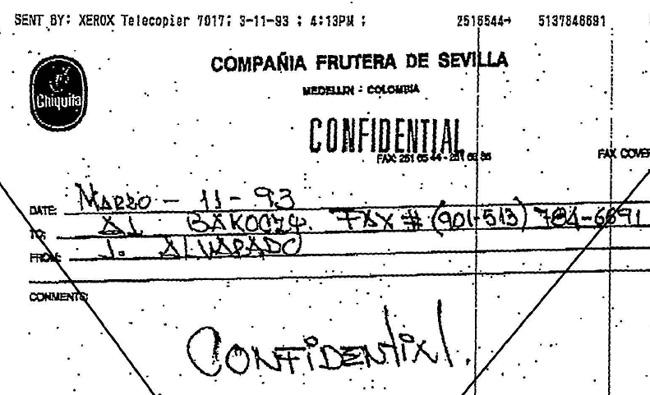

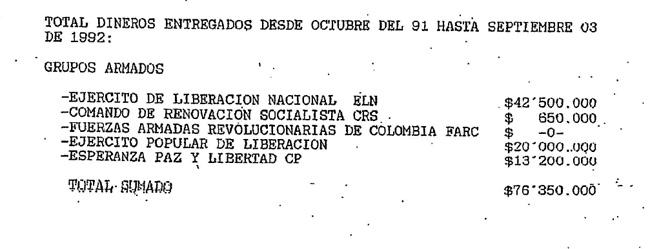

One of the earliest available reports on the guerrilla payments was prepared by Colombia security chief Juan Manuel Alvarado and faxed to his boss, the longtime head of corporate security in Cincinnati, Alejandro “Al” Bakoczy, on March 11, 1993. Alvarado’s report covers payments made through so-called “Citizen Security Accounts” from December 1991 through December 1992. Alvarado said his team was more comfortable making deals with the ELN and the FARC, since these larger, more established groups had a “widely-respected hierarchical structure that is adhered to before any decisions are made.”

In the first years of the 1990s it was the ELN that received the lion’s share of Chiquita’s guerrilla payments, in part because “from the beginning it had complete knowledge of the conformation of Banadex” and could thereby justify charging higher fees than other groups. The ELN also maintained a strong presence in the banana-producing zone of Magdalena, where another Chiquita subsidiary known as Samarex was located.

The total amounts to be paid to the groups were set forth each year along with a schedule laying out when each payment was due. The sums were not imposed by the guerrillas so much as they were the result of a negotiating process. As John Ordman, a regional manager who served as a bridge between Chiquita’s Colombia operations and top executives in the U.S., explained in his testimony to the SEC, “you don’t just pay what you’re told or you’ll end up paying a filthy fortune. I mean, you’ve got to negotiate, you’ve got to say I can’t pay, I’m not going to pay, you’ve got to kind of be dragged to the wedding kicking and shouting or it really gets out of hand. But you have to kind of know when to eventually show up or it also gets out of hand.”

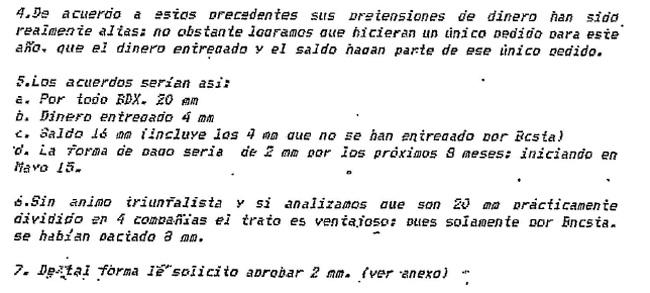

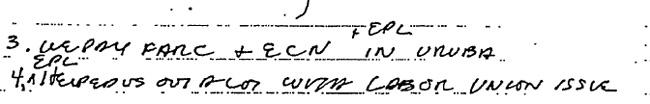

For example, in 1993 the company negotiated the ELN’s initial request for 20 million Colombian Pesos down to 12 million. But this was still too much for the person who approved the payments, who wrote in the margins of one record, “To me 12 [million] is too much for these guys. . . What kind of deal is that?”

The payments allowed the company to continue its operations. And even while none of the records associated with the ELN openly suggest that the money was offered in exchange for any service, the document below shows that in some instances Banadex officials were interested in establishing a quid pro quo with the group. “As with R [a reference to the FARC, known by the color code Rojo or Red] they shouldn’t block anything we do with sindicato [labor union].”

At the beginning of the 1990s, an intense political debate within the ELN resulted in the creation of the dissident CRS faction that laid down its weapons in April 1994. For the company, the creation of this organization from the body of the ELN was a significant concern since they believed that the splinter group also knew the true extent of Chiquita’s holdings in Colombia.

“Brown [Café, a reference to the CRS], as a relatively new dissident group, is eager for money and uses any mean necessary to get it,” according to the “Citizen Security Accounts” report prepared by Alvarado for Bakoczy. In one incident, the CRS kidnapped an individual connected to Chiquita as a way of signaling it was an independent organization to be dealt with separately and not under the previously-negotiated accord with the ELN.

Nevertheless, the communiqués from the security staff show that CRS was never seen as a serious threat and received only a small fraction of well over one million dollars in payments to Colombian guerrilla groups.

Accords with the FARC

According to the Chiquita accounting records, between 1991 and 1992 the FARC did not have much contact with the company and in particular did not make demands for money. A report from the security staff said that frequent confrontations with the Colombian Army kept the guerrillas too busy to arrange meetings during those years.

Chiquita, nevertheless, did not doubt the extent of the FARC’s power and influence in Urabá. “It is so influential that through a single order it has the ability to paralyze operations in the production areas, generating problems for commercial and social order,” according to a report from Compañía Frutera de Sevilla dated September 4, 1992. The staff of the Chiquita subsidiary in Santa Marta said the FARC resorted to extreme violence in cases where people did not comply with their demands.

The FARC shared the company’s concern about the proliferation of new subversive groups in search of money—a situation that had led to a “destabilization of the zone,” according to the company’s reports, and confrontations among the competing factions.

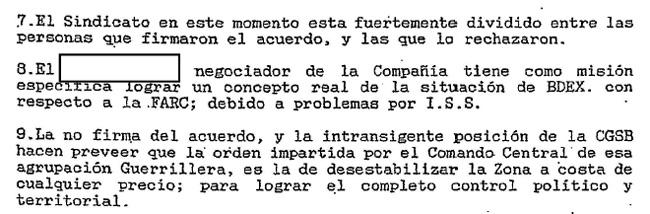

This survey of the general security situation in and around company facilities in the port city of Turbo also refers to an agreement between the Institute for Social Insurance (Instituto de Seguros Sociales), the Banazuñiga group and the labor unions. One of the union representatives, who the company said was clearly “allied with the FARC,” had refused to sign the accord and convinced others to do the same. For Chiquita, it thus became a priority to gain a better understanding of the “real situation” with the FARC.

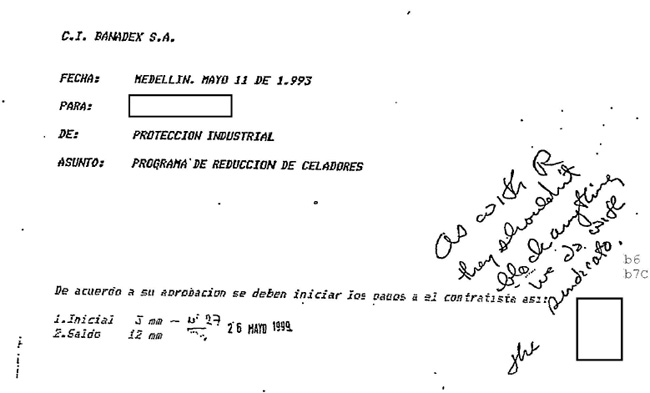

By 1993 the balance had shifted, and soon the FARC became the leading recipient of Chiquita’s cash payments to guerrilla groups. In a request for disbursement on May 11, it is evident that the FARC had identified three of the farm groups that worked with Chiquita Brands and knew the names of staff members. But although the FARC was now demanding more money from the company, the company still did not consider the payments to be significant. In the document below, security staff characterize the new arrangement with the FARC as “advantageous.”

The records show that there were not any serious setbacks in the company’s relationship with the FARC, and that even the intermediaries said that it was “easy” to negotiate with the oldest rebel group. When a problem arose, such as a stolen vehicle in Magdalena, they would simply set up a meeting and resolve the problem. As was the case with the ELN, records from May 1993 show Banadex management seeking “an understanding” with the FARC (“R”) that they not “block anything we do with the sindicato.”

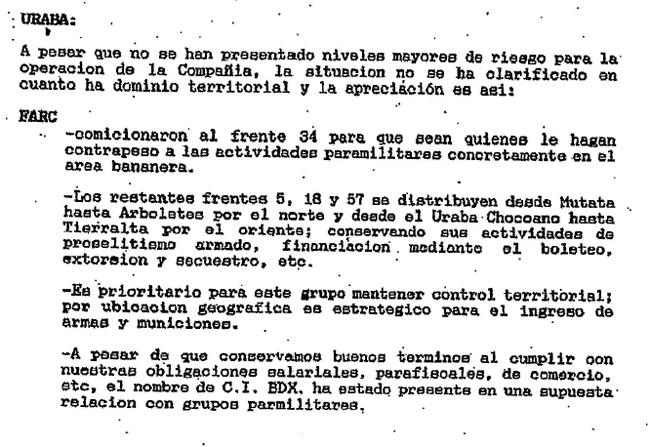

In 1995, with the arrival in the zone of the increasingly powerful United Self-defense Forces of Córdoba and Urabá (ACCU), under the command of Carlos and Vicente Castaño, company officials seemed concerned about a deterioration in relations with the FARC. “Despite the fact that we fulfil our obligations in terms of salary, taxes, trade, etc., the name C.I BDX has been mentioned in a supposed relationship with paramilitary groups,” according to a security report from September 18, 1995.

Over many weeks, and through various channels, VerdadAbierta.com tried to communicate with members of the FARC Secretariat, including Rodrigo Londoño Echeverri, alias “Timoleón Jímenez,” top leader of the insurgent organization, and Luciano Marín Arango, also known as “Iván Márquez,” chief negotiator in peace talks with the national government. It was Márquez who led the group’s operations in Urabá during the era when Chiquita was making payments to the FARC. But despite a number of attempts to get their valuable perspectives on the matter, there was no reply, raising doubts about the group’s willingness to come clean and tell the truth before the tribunals of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace and Colombian society.

The Fractured EPL and the Arrival of Paramilitaries

On March 1, 1991, in camps around the country, a little more than 2,000 guerrillas from the EPL abandoned the armed struggle and embarked on the construction of the Esperanza, Paz y Libertad (Hope, Peace and Liberty) political movement. Around 150 guerrillas did not demobilize and reorganized under the leadership of Francisco Caraballo, who began to launch attacks against his former comrades with assistance from the FARC.

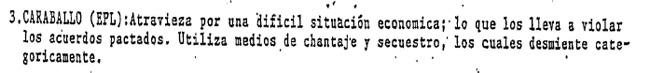

In their pragmatic reports, Chiquita’s security staff in Colombia registered deep concern about the proliferation of new armed groups and the infighting among them, and decided that it would be necessary to come to separate agreements with each group. In the “Citizen Security” report dated September 1992, for example, the company said the Caraballo group was committing crimes to collect money. Among other things, they hijacked and raided the company’s trucks along access roads from Medellin to the coast, so Banadex chose to use the name of third parties to transport their merchandise.

“I acknowledge that we imposed a series of fees, and the precise deployment that we had in Urabá allowed us to broaden the base the provided the tributes, and we collected what was necessary for our subsistence and the development of the organization,” Francisco Caraballo told VerdadAbierta.com. “These tribute payments, in the majority of cases, were a kind of agreement. It is a very special situation, some collaborated, and I should say it clearly, so as not to create problems, so they collaborated, you could say, voluntarily.” Caraballo added that, “as revolutionaries, we were not trying to become a wealthy organization, but something much less.”

Former EPL insurgent Jaime Fajardo Landaeta, one of the leaders who pushed for peace accords with the national government, said that following the demobilization the majority of the resources that the ex-guerrillas received came from the government: “We had a very complicated problem: the people left who were left in control of the organization’s resources at the time of the demobilization were from the secretariat, which was in the hands of Francisco Caraballo and two others, 'Danilo' and 'Eduardo', who did not negotiate the demobilization.”

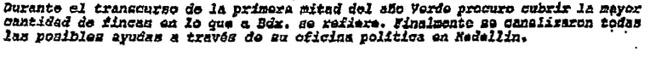

The group also got support from the Asociación de Bananeros de Colombia (Augura) to launch its political movement, payments that were permitted under Colombian law. In the case of Chiquita Brands, according to its own reports, during the first half of 1992 members of the Esperanza group tried to collect funds from as many Banadex farms as possible, after which the company agreed to channel payments through Augura.

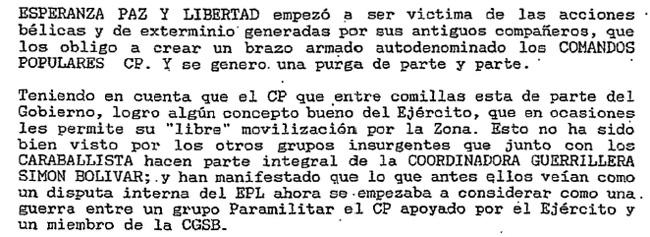

From the moment of the demobilization, dissidents under Caraballo working with the FARC launched an extermination campaign against members of Esperanza, Paz y Libertad, who they viewed as traitors. As a result, a group from Esperanza decided to rearm to defend themselves, creating the Comandos Populares (mentioned above).

“The dissidents of the EPL formed the group because they did not think that the peace process had provided them with any space, so they left and they took up arms; the others, the Comandos, they believed the leaders of Esperanza, Paz y Libertad were not helping with security issues, that the leadership had their own vehicles and their own security schemes, so they were not interested in the security of the others,” explained Mario Agudelo.

Chiquita viewed the Comandos as “the armed wing” of the Esperanza political movement and increasingly came to see the militia as something more akin to a right-wing paramilitary group. As early as 1992 the Colombia security team said the group was widely considered to be “on the side of the government” and that the Army “on occasions allowed them to move freely around the zone.”

The security staff said the Comandos Populares relied on the same tactics they used “when they were part of the guerrilla group,” including “threats, intimidation, blackmail, etc.,” adding that banana growers had filed complaints against them through Augura. In the case of Chiquita, the group had only asked for little things like “drugs, boots and ammunition.”

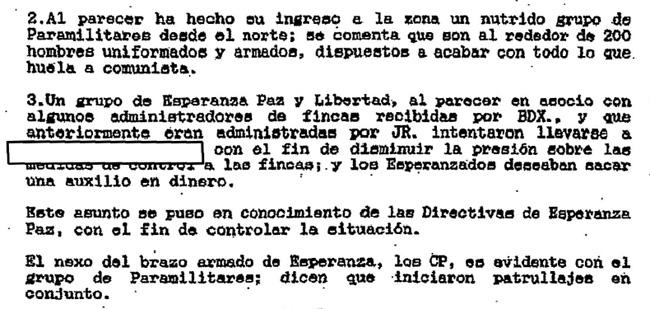

From June 1992 through May 1995, Chiquita transferred at least 36,000,000 Colombian Pesos to Esperanza and the Comandos Populares, primarily through Augura. By that point, Colombia’s security team reported the existence of a “nexus” between the Comandos and a group of paramilitaries that had recently arrived in the region and who were “ready to do away with everything that smells communist.” The Comandos were said to have “initiated joint patrols” with the newly-arrived paramilitaries, according to the report from Chiquita’s subsidiary in Colombia.

Whatever concerns the company may have had about the tactics employed by Esperanza and its allies in the Comandos Populares, by 1996 the general impression held by senior Chiquita officials in Cincinnati was that the groups had been helpful. In a September 1996 meeting with internal auditors, Al Bakoczy, the corporate security chief in Cincinnati, said that Esperanza (here as “EPL”) had “helped us out a lot with the labor issue.”

Why did the guerrilla payments stop?

The arrival of paramilitaries to the zone in 1995 was a watershed moment for Chiquita. Two years later, the guerrilla payments had ceased completely, and the company had begun to redirect the money toward paramilitaries and their allies in the Convivir self-defense groups. The key moment, by most accounts, was a meeting between Carlos Castaño, leader of the ACCU paramilitary group; Charles Keiser, general manager of Banadex; and Reinaldo Escobar de la Hoz, a lawyer for Chiquita’s Colombian subsidiary.

Irving Bernal Giraldo, who was a member of Augura and one of the founders of the Convivir Papagayo, which secretly directed money to paramilitary groups, remembered this episode in a June 30, 2015 hearing before the Colombian prosecutor’s office: “You all are giving money to the guerrillas and I am not going to allow that,” Castaño told them. Bernal, who had just been released from a kidnapping, denied the paramilitary chief’s accusation and floated the possibility that Augura could finance Private Security Cooperatives such as the Convivir.

“Then we both calmed down a bit, and he looked at Mr. Keiser and said to him, ‘But you are giving money to the guerrillas,’ to which Keiser nodded.” Bernal said Castaño and Keiser talked in private after which the paramilitary chief said, “Now the matter is clear.”

The story behind this meeting is, for the most part, hidden history. In 2007, Chiquita Brands admitted that it paid $1.7 million to paramilitary groups and paid a $25 million fine to the U.S. government. In Colombia, the company has not indemnified a single victim, and the judicial process has been stuck, immobile, for ten years.

Will the alleged financiers of the conflict in Urabá remain unpunished in the face of all of this new evidence? Wait until next week and the fourth and final installment of the series of articles by VerdadAbierta.com and the National Security Archive.

Document 01

Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Department of Justice

.

Document 02

Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Department of Justice

.

Document 03

Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Department of Justice

.

Document 04

Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Department of Justice

.

Document 05

Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Department of Justice

.

Document 06

Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Department of Justice

.

Document 07

Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

.

Document 08

Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Department of Justice

.

Document 09

Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Department of Justice

.

Document 10

Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Department of Justice

.

Document 11

Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Department of Justice

.

Document 12

Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Department of Justice

.

Document 13

Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Department of Justice

.

![“To me 12 [million] is too much for these guys. . . What kind of deal is that?” “To me 12 [million] is too much for these guys. . . What kind of deal is that?”](/sites/default/files/styles/wide/public/thumbnails/image/10_2.jpg?itok=f1nXNpI8)