Washington, D.C., 24 August 2022 - As the U.S. contemplated a more aggressive drug war strategy in Colombia in the 1980s, top intelligence officials said success there would require “a bloody, expensive, and prolonged coercive effort” that, even then, was not likely to have an impact on the U.S. drug market, according to a declassified report published today by Colombia’s Truth Commission and the National Security Archive.

The 1983 Special National Intelligence Estimate, featured in the Washington Post, is among a massive trove of declassified U.S. records gathered and organized for the Commission by the Archive that is the focus of a special event today in Bogotá to introduce the Truth Commission’s digital library to the academic community. Archive senior analyst Michael Evans joins Truth Commissioner Alejandro Valencia Villa and other distinguished panelists at Colombia’s National University to celebrate the launch of the platform and to share highlights from more than 15,000 previously classified documents on Colombia’s conflict.

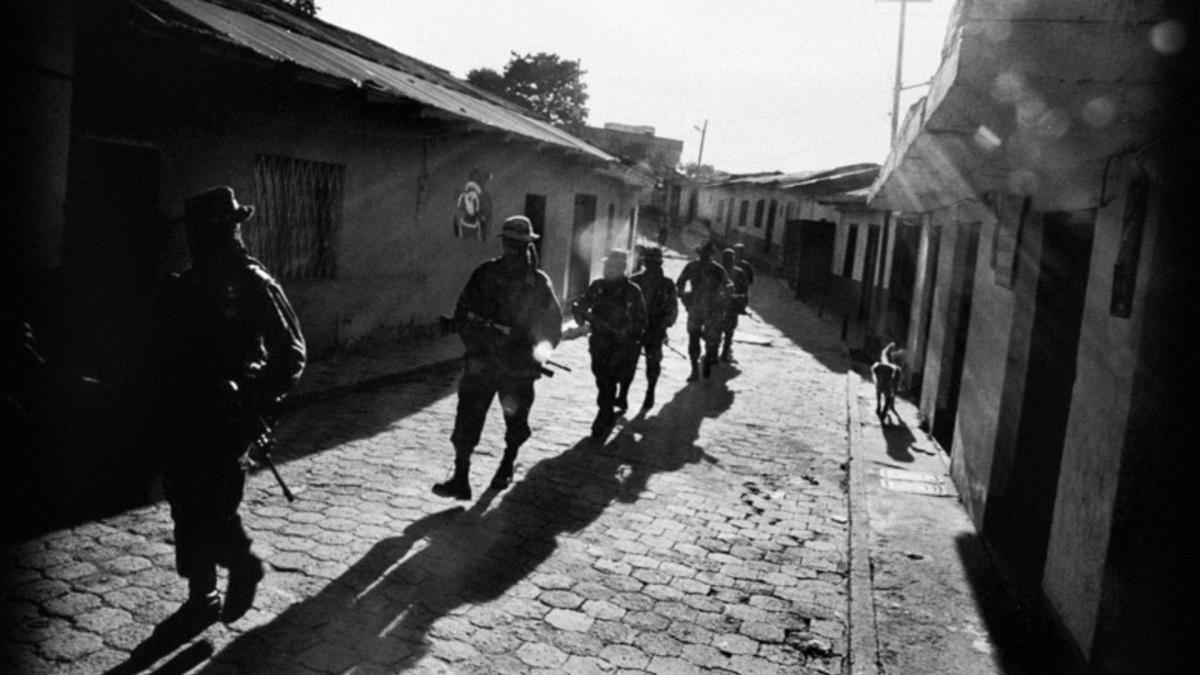

The event also features a light projection designed by visual artist Mireaver (Diana Pareja) that literally “sheds light” on dark chapters from Colombia’s history, using a light projector to beam enlarged images of former U.S. national security secrets onto an exterior wall at the university. The new work “takes fragments from U.S. declassified archives and reconfigures the materials in an experience of sound experimentation and video mapping.”

Today’s posting focuses on the 15 records, described in detail below, that are featured in her extraordinary work. The documents are drawn from three document collections prepared by the Archive and published by the Commission earlier this month as special annexes to its final report. These document readers explore three central themes of the conflict, reflecting the views of U.S. diplomats, policymakers and intelligence analysts across three decades and underscoring some of the Commission’s major findings and recommendations. Researchers from the Commission cited hundreds of declassified documents in the narrative reports and case studies on the conflict.

Documents 1-5 are selected from an annex of declassified documents from the period when the U.S. first began to treat international narcotics trafficking as a national security issue, deepening the U.S. role and initiating drug war strategies that the Truth Commission says worsened the conflict. These records, including intelligence estimates and high-level policy papers, show U.S. officials at times struggling to identify non-corrupt actors to work with in Colombia, while concerns about official ties to drug cartels and the emergence of new, more agile, trafficking groups often overshadowed drug war “successes.”

The second set of records (Documents 6-10) are drawn from the annex on Plan Colombia, the multi-billion-dollar U.S. aid package that greatly expanded the fumigation of drug cultivations and the U.S. footprint in Colombia’s war. Records featured here underscore the Commission’s findings about the dramatic human cost of these more aggressive operations, detailing, in one U.S. Embassy cable, U.S. concerns that they would “contribute to the social protests, and perhaps violence, that likely will follow in the wake of planned aerial eradication efforts.” In another memo, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld considers options for direct U.S. military intervention in Colombia, asking advisors “to decide what victory would be, and then think through a plan to achieve what we decide to characterize as victory.”

Documents 11-15 derive from an annex that look at links between Colombian state security forces and illegal paramilitary groups that the Truth Commission says constituted “the most violent armed actor,” responsible for “47% of the dead and disappeared victims of the armed conflict.” The records support the Truth Commission’s finding that the groups were born of an alliance between ranchers, local elites, narcotraffickers and members of the police and military who used the cloak of anti-communism to seize land and aggrandize their personal wealth. One U.S. Embassy report, for example, described how anti-guerrilla paramilitaries backed by ranchers and the army were “used to drive peasants off the land … permitting the major ranchers to consolidate and expand their landholdings.”

The database, the annexes and other National Security Archive declassified resources on Colombia and the conflict are available as part of the Truth Commission’s Truth Clarification Archive (Archivo del Esclaracimiento de la Verdad). The new platform provides various ways to explore the declassified records. In addition to the annexes, users can browse the complete database or navigate through 52 thematic research files (the “carpetas”).

Of special interest is a March 2021 letter in which Truth Commission President Francisco De Roux asks President Biden to order the accelerated declassification of U.S. federal records on various aspects of the conflict. The request, which remains pending as the Commission prepares to close its doors, is a to-do list of declassification priorities for the U.S. government as Colombia moves to consolidate peace and implement the recommendations of the Commission—among them, a recommendation to relax and reform restrictions that keep most of Colombia’s own intelligence archives hidden from the public.

The Documents

DOCUMENT 1 [NARCOTICS ANNEX DOCUMENT 04]

CIA CREST database

A special annex to the first U.S. National Intelligence Estimate on narcotics in Colombia outlines “Links Between the Narcotics Trade, Guerrilla Groups, and the Military,” finding there is at least “some connection between MAS and some military or police officers,” referring to the trafficker-run death squad known as Muerte a Secuestradores (MAS).

There has been speculation since [the group was formed] that the police and even the military are linked with MAS. Not a single important member of MAS has ever been apprehended. This could indicate that the original vigilante group has disbanded and that common criminals or other “rightwing” groups use its name to cover their own involvement in violence. More likely, it indicates that there is, indeed, some connection between MAS and some military or police officers.

…

[Deleted] while the Colombian military does not officially assist the MAS a number of individual military officers have had operational contacts with it and that the MAS is now highly compartmented and organized-employing safehouses and message centers. This compartmentation is said to account for the difficulty the AG has had in his attempts to investigate it. Moreover, many of the killings done in the name of MAS may have been done by military officers who use the name as a convenient cover.

It seems probable that some military personnel are both trading on the MAS name and are at least indirectly involved in its activities. At the same time, MAS appears to have expanded into a cluster of vigilante groups (like cattlemen and ranchers) determined to resist the kidnappings and extortion efforts of both insurgent groups and common criminals.

Whatever the extent of the ties between MAS and the military, they can only serve to further inhibit forceful action against the major narcotics traffickers associated with MAS. This would be true even if those military officers involved simply work with MAS against their common enemy, the insurgent-extortionist groups. It would be even more worrisome if, over time, the military became more actively involved in the lucrative business.

DOCUMENT 2 [NARCOTICS ANNEX DOCUMENT 23]

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library

The outlines of a major shift in counternarcotics and Colombia policy are evident in this discussion among top U.S. policymakers of the implications of the release of Medellín Cartel leader Jorge Luis Ochoa from prison. With participants wondering aloud whether narcotraffickers had taken charge in Colombia, the interagency group agrees on general language for a message to President Barco and on the need to work behind the scenes to impress upon him and other Colombian officials of the need to take a more aggressive approach to the drug war.

Summary: … Participants agreed that [the release of Ochoa] raised serious questions about the ability of the GOC to deal effectively with the drug situation. Participants also agreed that we must continue to work with the GOC and that our immediate task is not simply retaliating for Ochoa’s release but pressing the GOC to take strong additional steps to confront the traffickers.

…

Who Rules in Colombia?

Articulating the concerns of many participants, [Associate Attorney General Steve] Trott asked if Ochoa’s release indicated that the traffickers [were in charge] and there was no longer a government in Colombia with which we could deal. Other participants noted that the GOC would become irrelevant in a country run by traffickers. The ambassador explained that, barring an unlikely political catastrophe, we would have to continue dealing with Barco for two more years and that there was no indication that Barco knew of in advance or had anything to do with Ochoa’s release. [Assistant Secretary of State for International Narcotics Matters] Ann Wrobleski stressed that the Colombians themselves would have to decide who was really in charge; we could not decide for them.

Keeping Our Eyes on the Ball: Doing the Doable

The important point to consider, according to Wrobleski, was that the USG had important narcotics-related objectives in Colombia other than Ochoa’s re-arrest (which in any case would probably not occur soon) and that we had to concentrate on persuading Barco to do the doable. Barco should be reminded that indecision and inaction does “not keep faith” with the well-known Colombian sacrifices in the drug war. The ambassador noted that the [U.S. Embassy] charge had pressed Barco (and received a positive response) on increased eradication, interdiction and major lab destruction. [Ambassador] Gillespie said we had to determine for ourselves what would be appropriate milestones to establish as evidence of Colombian resolve, determine what negative/positive feedback we could supply, and provide loud, clear signals of approval/disapproval in one voice.

[U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for South America] Bob Gelbard, Gillespie and others noted that we must clearly demonstrate that the “entire” USG, not just the anti-narcotics community, gives the drug war a “high priority” and that the narcotics issue inevitably affects the entire range of US-Colombian relations…

Without Losing the Game

Ambassador Gillespie suggested that our actions be carefully constructed to present the strongest possible message to the GOC without losing the (for the moment) generally positive support of the Colombian media. All agreed with Trott’s observation that private demands for GOC action would be more effective than public bashing…

[Chief of DEA Operations] Dave Westgate suggested that hitting the major traffickers (and showing them that extradition is not the only effective weapon against them) should still be our (and the GOC’s) goal. GOC benchmarks would include: A) Seizing trafficker assets and raiding their property. B) Hitting major cocaine HCL labs and C) Increasing anti-narcotics cooperation with Peru and Brazil.

[Department of Justice Criminal Division head] Bill Weld…thought the GOC should hit more important labs, increase interdiction, begin aerial eradication, find a workable means for quick extraditions, allow increased DEA involvement in GOC law enforcement operations and improve procedures to obtain permission for US forces to board Colombian flag vessels.

DOCUMENT 3 [NARCOTICS ANNEX DOCUMENT 27]

CIA CREST database

In a National Intelligence Estimate, the U.S. Intelligence Community finds that the “greatest threat to the stability and integrity of the [Colombian] political system over the next two years will stem from the narcotrafficking groups.” The NIE predicts that “higher levels of external support will be necessary” if the Colombian “military is to sustain both a counterinsurgency and antinarcotics effort at current levels or beyond.” Even so, the Colombian counternarcotics campaign was “not likely to have a major impact on the US drug market,” according to the intelligence estimate.

Compared with the guerrillas, traffickers will be better equipped, have superior intelligence networks, have greater influence in urban areas, and be more ruthless. Their threat extends beyond violence and intimidation—their rapidly increasing rural real estate holdings, for example, will be a major impediment to the government’s land reform program.

Drug-related violence—including terrorism against the government, civilian and business sectors, and trafficker-financed rightwing assassinations of leftists—will be a potent destabilizing force. The overlap and interrelationships between trafficker organizations and local rightist paramilitary groups will sustain very high levels of political violence. This situation is likely to be exacerbated by the inclination of some military and police officials to condone and even support paramilitary violence against the left.

…

President Barco is almost certain to stay the course and his most probable successors in August 1990 are more likely to pursue his tough security policies than to reverse them. They also would maintain conservative probusiness programs that are key to investment and continued, if somewhat slowing, growth.

The residual strengths of the Colombian state make it a prospective strong partner for the United States in helping to combat the drug problem and to continue to anchor democratic rule in Latin America, but the magnitude of its problems will make it more reliant on foreign aid. Government tactical progress against the insurgents will begin to be undercut by the logistic strains of sustained armed forces participation in antidrug operations by mid-1990 unless offset by increases in external assistance. In short, if the military is to sustain both a counterinsurgency and antinarcotics effort at current levels or beyond, higher levels of external support will be necessary. In addition to boosted US aid levels, demonstrated US initiatives in the narcotics battle at home--stiffened penalties, actions to counter US drug money laundering, and efforts to reduce domestic drug consumption--will be important considerations for Barco's successor in choosing his drug policies.

Even then, the antidrug campaign is not likely to have a major impact on the US drug market. If Colombia maintains its present level of effort over the next year and beyond-and there is a good chance it will have the potential to disrupt the Colombian trade by causing traffickers to reconfigure and relocate some operations, forcing cutbacks in processing and exports. Nevertheless, the drug industry is extremely resilient, and for the campaign to have much more than a passing effect on drug supplies in the United States over the next year or two would require efforts of similar magnitude in other Latin American countries. Lacking this, successes in Colombia paradoxically will prompt drug traffickers in other countries, including those outside the Andes, to take up the slack. Permanently reducing the size of the cocaine industry will require a reduction in worldwide demand.

One price of the antidrug campaign in Colombia for the United States will be the terrorist risk to US facilities and personnel. These are important, if secondary targets of insurgent and trafficker violence, and they will be in higher profile as new US assistance comes into play and if drug kingpins are extradited. Attacks on the Embassy and attempted kidnappings of senior US officials will be well within the range of options considered by the traffickers and, to a lesser extent, the insurgents. Strikes at other US targets in Latin America, Western Europe, and even inside the United States are within the narcotraffickers' capabilities.

DOCUMENT 4 [NARCOTICS ANNEX DOCUMENT 34]

FOIA

U.S. Ambassador Busby recounts meetings with Defense Minister Rafael Pardo and Gen. Miguel Gómez Padilla, who had just resigned from his position as director of the National Police, about plans to create another specialized task force to take down the Cali Cartel leadership. Like the Medellín Task Force, the new unit would be supported by multiple U.S. elements, including the DEA’s Bogota Country Office (BCO) and Joint Special Operations Command {JSOC}, a secret military intelligence unit. Gómez tells Busby that he has serious concerns about handing over the new Cali task force to his replacement, Gen. Octavio Vargas, director of the Medellín Task Force.

[Pardo] said he intended to create a small, very specialized unit of vetted (polygraphed) police and military officers, possibly some 30 individuals, to pursue the four top kingpins and their principal “15-20 lieutenants.” He asked for the same type of U.S. support—DEA, [redacted], and JSOC [U.S. Joint Special Operations Command] elements—to this unit as had been provided to the anti-Escobar task force (Bloque de Busqueda) in Medellin. He requested assistance in training the unit, as well as with operations planning and intelligence operations. Pardo said that only he, the President, myself, and Gomez Padilla would be aware of the cell, the U.S. support to it, or the specific targets of their operations.

…

As we sat down Gomez Padilla informed me of his resignation. I asked Gomez if he felt that the operations in Cali would proceed on schedule given Pardo’s absence, and his own resignation. He replied that the GOC would carry out the large-scale operation, but that this was simply “smoke,” designed to send a signal. He said Vargas would coordinate the operations and he had no doubt they would commence.

Gomez then said the real operation was the small unit Pardo and I had discussed. He said he wondered whether he wanted to “hand over” this operation to Vargas, adding that the future of this unit was his major preoccupation in resigning. I replied that we had some concerns about Vargas. Gomez Padilla stated that while he had no facts, he had reservations about Vargas himself, and advised me to wait until Pardo [who was in the hospital] was back on the job to pursue this concept any further.

I told Gomez we were confident Vargas had had contact with Cali during the hunt for Escobar and that we had speculated as to whether it was operationally oriented, to gain useful information. “That was not the case,” replied Gomez. Gomez said that he thought the ideas Pardo and I discussed were perfect, and with the same type of support which had been provided to the Bloque, would work well in Cali. With [deleted] DEA the law enforcement and JSOC [U.S. Joint Special Operations Command] training the operational unit, the concept was sound. But, he said security was paramount and Pardo was the man to talk to. He said he was not certain that the president had been briefed, but felt strongly that Vargas was not the man to carry the plan forward. He said it would be foolish to go forward with these operations without political cover and approval, and that needed to be decided between Gaviria and Pardo. Since Gaviria would not trust anyone but Pardo with such a delicate matter, this should be put on hold until Pardo had recovered from his surgery and had returned to work.

Comment: We are still reeling from the one-two loss of Pardo and Gomez Padilla. But Pardo will be back, we are fortunate that it is Christmas and there will be a break, and there is time to regroup. Our plan is very much alive and a small unit, comprised of two distinct cells, [deleted] is the only effective means by which the GOC can combat the Cali Cartel. [Deleted] team already in place here in Bogota, which is already working on supporting operations in Cali.

We see the wisdom in Gomez Padilla’s advice to wait a few weeks and have thus authorized the majority of the JSOC elements in country to go home over the holidays. As requested, we will forward in coming days a revised mission statement along with a fleshed out version of the concept. As for Vargas, we’ve long suspected him of being too close to Cali, and Gomez’ fears are ours. All the more reason to proceed cautiously in this matter.

DOCUMENT 5 [NARCOTICS ANNEX DOCUMENT 40]

FOIA

This cable provides “the [U.S. Embassy] Bogota Country Team’s (CT’s) musings on the status of trafficking organizations in the post-Cali world,” finding “a more diffuse and decentralized drug business” consisting of “small, loose confederations” meant to minimize risk.

The foreign counterdrug strategies employed by the U.S. government over the past seven years have been highly successful at what they were designed to do; principally, to target and arrest the leadership of major drug trafficking organizations in the Andean ridge region. We have dismantled the Medellin and Cali cartels as they were once known. Where once drug mafias viewed themselves as invincible, their leadership is either dead or in prison. This was never the ultimate goal, however; the objective always has been to attack all elements of the drug trafficking enterprise to have any real impact, destroying the complete organization and reducing the flow of drugs to the U.S.

…

With the downfall of the Cali mafia, the Andean ridge’s new generation of leading traffickers, as predicted, is operating a more diffuse and decentralized drug business. The Cali mafias’ [sic] vertically compartmented, tightly controlled, immense organization has been replaced by small, loose confederations characterized by shifting alliances among specialized groups, as producers, suppliers, transporters, and distributors, through less fixed business arrangements, all seek to minimize each individual’s risk while continuing to traffic. As a result of the breakup of the Cali mafia monolith; the norm is now smaller, lower profile, and fairly-insulated organizations. One telling sign of the change in operating style is that Colombian traffickers now tend to stay away from the legions of bodyguards, which were a must-have accessory during the Cali kingpin days. These traffickers want to avoid the risk of too many people too close who might leak information, submit to bribery, or be arrested. Nor are overt political and social ties as actively sought as in the past, again to maintain a low profile and avoid the security risks that come with notoriety.

It is important to realize that the new, looser arrangement does not represent disarray in the trafficking world. Indeed, the loss of centralized control exerted during the reign of the Cali mafia has not diminished the flow of cocaine to the U.S. The multitude of then-dependent traffickers did not miss a beat when their Cali bosses were jailed. Moreover, the lack of control allows for ever more players to join in the game, further diffusing the business and even potentially increasing cocaine flows.

…

IDENTIFYING TARGETS ON THE NEW FIELD

As a result of these changes in trafficker operating style, identifying the most important new targets has not been as simple a matter as in the past; indeed, the joint Colombian-U.S. effort to identify the top priority of narcotrafficker groups, and to target them for investigation, prosecution, and dismantlement, was an exercise that preoccupied Washington and Colombian counterdrug agencies in 1996.

As the focus shifted to identifying the most important traffickers, operational emphasis shifted away from purely raid and capture-focused operations so characteristic of the days in 1994 and 1995 when the Army and Police search units in Cali mounted hundreds of raids against kingpin targets. Those fast paced high profile operations have been replaced by the slower, often painstaking detail work of gathering individual pieces of intelligence and putting together a picture of traffickers, their associates, and modus operandi. In a December meeting Colombian prosecutor general Valdivieso predicted that it would be difficult to prosecute the second generation for drug trafficking since no drug charges are currently pending against them in the U.S. or Colombia; he said that the Fiscalia would at least try to prosecute them on illicit enrichment and money laundering charges.

REVISITING THE PRIORITIES

Obviously, there is no dearth of trafficking targets in Colombia; in September 1996, among the linear targets in the region, 12 were connected to Colombia. This does not include the myriad of targets of opportunity, nor all the targets that the Colombians themselves want to pursue, which may or may not be the most important in terms of U.S. counterdrug interests. A continual effort must be made to stay focused on a defined and relatively small group of traffickers in order to have any success in disrupting and dismantling key groups and supporting important U.S. domestic law enforcement cases. It is also vital as well to try to keep the Colombians, with whom the Embassy—DEA and ROAL [CIA]—works, focused.

To have the greatest impact on the flow of narcotics from the region, the Andean ridge Country Teams are redoubling efforts against transportation organizations… [M]embers of the Bogota CT have designated the Bernal Madrigal, alias “Juvenal,” transportation organization as a linear target. The Colombia CT is focusing additional targeting and intelligence collection efforts against organizations using aircraft to transport HCL and cocaine base south of the Andes mountains. Given there are no railroads, the rivers run east and west, and the lack of available roads, we view the airplane as the one indispensable (and therefore vulnerable) link in the narcotics transportation chain.

By focusing on aerial transportation trends in southern Colombia, we will identify major cocaine HCL production facilities and the organizations responsible; our experience thus far indicates that cocaine production organizations in Colombia have located most large HCL labs in the vicinity of the most widely-used clandestine airstrips. Our focus is on the organizations, transportation and HCL production, which will identify the most important trafficking organizations trying to ship cocaine north.

Also in early 1997, consideration was given to updating the entire Bogota Country Team targeted organizations list, as successful counternarcotics operations had whittled down the original list considerably. As a result the Bogota CT’s new target list consists of only seven organizations, four of which include designated linear targets. The above mentioned “Juvenal” transportation organization, and the Northern Valley trafficking group directed by the Henao Montoya brothers currently are receiving the highest priority by the Country Team. In addition, remnants of the Rodriguez Orejuela organization (a linear target) remains [sic] a Bogota Country Team target. Non-linear targets include Northern Valley trafficker Jose Nelson Urrego, Vicente Rivera Gonzalez, and the “Don Celso” organization. The seventh member of the list, noted trafficker Justo Pastor Perafan, was captured by Venezuelan authorities on April 18, 1997.

…

THE ROLE OF COLOMBIA’S INSURGENTS IN THE DRUG TRADE

Further complicating efforts against trafficking organizations in Colombia is the presence of large rural-based guerrilla groups, the FARC in particular, many of whose fronts are exploiting drug-related activities to fill their coffers and are diversifying their roles in the narcotics trade. Available information indicates involvement by FARC units in almost all aspects of the drug trade in the sources zone of Colombia, with their primary activity centered on supporting trafficker operations and providing security. While assertions by the Colombian Armed Forces that the guerrillas have become a “third cartel” are exaggerated, the FARC in recent years has more aggressively protected its drug-related interests by attacking counternarcotics operations and by organizing protests against government coca eradication efforts.

DOCUMENT 6 [PLAN COLOMBIA ANNEX DOCUMENT 1]

FOIA

This report from the CIA’s Office of Asian Pacific and Latin American Analysis assesses the impact for U.S. interests of increasing guerrilla attacks on petroleum industry infrastructure, finding overall that they “deprive Bogota of important tax and foreign exchange revenues, expose US investors to increased risks, reduce demand for US capital equipment exports, and damage fragile ecosystems.”

The report also points to the important role of non-state actors in the conflict, revealing, for example, that “at least one multinational company” working in the oil sector was “actively providing intelligence on guerrilla activities directly to the [Colombian] Army.” The report said that some multinational firms paid the Colombian military for protection, “a practice many firms want to phase out to avoid being linked to human rights abuses committed by some military groups.”

Despite the high costs for security and the repair of damaged infrastructure, most firms appear committed to riding out spikes in guerrilla violence, but few are taking steps to discover or develop new fields. Multinational companies spend eight to ten times as much on security in Colombia as they do elsewhere in the region, and exploration is at its lowest level since 1978, [deleted.]

Bogota is attempting to reassure investors by beefing up military protection for the sector and by allowing them to keep a greater share of new oil discoveries. While such measures may help somewhat, it seems unlikely that the Colombian security services will be able to significantly improve the overall security situation in the foreseeable future—a prerequisite for the country to meet its immense oil-producing potential.

…

[T]he presence of foreign firms has come to represent an important source of revenue for the ELN and one they would probably be reluctant to lose. These firms are a particularly attractive extortion target because they have considerable fixed investments at stake and the resources to meet guerrilla extortion demands, according to a defense attaché source. The companies deny paying such extortion fees, locally known as vacuna, but acknowledge that their subcontractors and workers may do so without their knowledge or approval, [deleted.]

…

Not surprisingly, multinational firms spend eight to ten times as much on security in Colombia as they do elsewhere in the region. Most of these firms keep large security staffs and, in some cases, pay the armed forces directly for protection—a practice many firms want to phase out to avoid being linked to human rights abuses committed by some military groups—[deleted] Several firms are currently negotiating with Bogota to establish terms for a joint security fund to be administered by Ecopetrol.

…

Despite the increasing security problems, the vast majority of oil companies seem intent on maintaining their existing operations. Oil sector investments in Colombia generally entail multibillion dollar setup costs but relatively low operating expenses. This gives existing producers a significant incentive to remain rather than divest, which would require selling fixed assets at a steep discount or a complete loss if plant and equipment were abandoned entirely, [deleted.] Multinationals at Cuisana, Cupiagua, and elsewhere, however, are responding to the deteriorating security situation by extracting oil at a much faster pace than would be optimal in order to maximize their long-term output [deleted.]

…

Bogota Struggling to Improve Security

Goaded by calls from multinational investors and concerns over the growing assault on the country’s primary export, Bogota is beefing up its already substantial commitment of military resources to protect oil production and transport infrastructure. Most notable, it is adding a new military unit to the effort—the 18th Brigade and its 2,000-3,000 troops—bringing to five the number of Army brigades that are heavily involved in energy sector production. The new brigade is headquartered in Arauca Department, where Cano Limon fields are located and the guerrillas are well entrenched. Bogota granted the brigade tactical control of aviation assets presumably to enable it to better patrol the pipeline and respond to guerrilla attacks.

The military’s problems confronting the guerrillas in oil regions, however, transcend manpower issues. Units use the bulk of their time and troops guarding refineries and pumping stations rather than actively seeking out guerrillas and preempting attacks on the pipeline [deleted.] Moreover, the vast expanse of territory over which oil activities take place leaves open the possibility that guerrillas will always be able to strike at points that are unguarded or lightly defended. The Cano Limon system alone has 135 wells and 485 miles of pipeline in a remote region. Moreover, the Colombian government alleges the guerrillas have informants in the oil Workers Union—Union Sindical Obrera (USO)—who provide information about oil sector security to them to facilitate attacks against the pipeline.

At least one multinational company is actively providing intelligence on guerrilla activities directly to the Army. The firm operates an airborne surveillance system along the pipeline to expose guerrilla encampments and intercept guerrilla communications, information it regularly shares with local military units, according to the defense attaché. [Redacted text] the military successfully exploited this information and inflicted an estimated 100 casualties during an operation against the guerrillas in Arauca in mid-1997.

Nonetheless, this type of close cooperation between foreign oil firms and the armed forces has a potential downside. The guerrillas could respond with revenge attacks against the companies or firms’ reputations could be damaged if they are linked to human rights abuses committed by security services using company-supplied information.

Outlook

…

[T[he recent actions taken by the military and multinational firms to improve security may impede the rebels’ ability to mount sustained attacks against oil sector infrastructure but will not prevent attacks altogether or significantly reduce the threat to oil sector employees. Indeed, in view of the expansive and difficult nature of the terrain, the longstanding shortcomings of the military, and the tenacity of the guerrillas it seems unlikely that Colombian security forces will be able to significantly improve the overall security situation in oil exploration and production areas in the foreseeable future. As a result, we are likely to see more private initiatives by domestic and foreign energy-related companies to combat guerrilla activities, including the deployment of high-technology security devices, the formation of vigilante groups, and the hiring of paramilitary groups.

…

Further escalation in guerrilla violence in the form of sustained attacks on pipelines or targeting of crucial elements of the oil infrastructure such as pumping stations, refineries, or export terminals would significantly increase the likelihood that some multinationals—including the country’s largest oil investor British Petroleum—would seriously consider exit strategies. In the face of such a threat, Bogota’s heavy reliance on oil sector revenues would leave it little choice but to further increase protection for the sector at the expense of decreasing security elsewhere.

DOCUMENT 7 [PLAN COLOMBIA ANNEX DOCUMENT 11]

FOIA appeal

This cable summarizes a visit by U.S. Embassy Political Officers to southern Putumayo, who find a thriving coca-based economy just weeks before the installment of the Colombian Army’s First Counter-Narcotics Battalion in Tres Esquinas. Embassy interlocutors mostly agreed that “the military and police were “complacent” about the AUC’s presence in the region” and that “’turning a blind eye’ would only corrupt the public forces, given the AUC’s own narco-financing.”

The entire culture of Colombia’s southern Putumayo Department – its economy, its security, its future – is intimately associated with the fate of its chief source of income, coca. Past governmental efforts to deal with the problem have failed miserably and only delayed paying the piper. With narco, guerrilla and paramilitary violence beyond the abilities of the (heavily bunkered) local forces of order, needed alternative development efforts will inevitably be hindered by the lack of security. This will contribute to the social protests, and perhaps violence, that likely will follow in the wake of planned aerial eradication efforts in the department in the coming months…

…

“Putumayo is coca”

To a one, interlocutors volunteered that Putumayo’s economy is coca-driven. Putumayo’s health is directly related to the health of the coca trade, they said… [Deleted] of the Army’s 24th Brigade, forward deployed to Santa Ana, echoed civilian officials in estimating that seventy percent of all money flowing through Putumayo comes directly from narcotics.

Poloffs were told that there is virtually no unemployment in urban Puerto Asis. A bustling town center of 25,000 “urbanites” (plus another 25,000 rural) makes Puerto Asis the department’s largest population and trading center. “It’s true; we have no beggars,” noted [deleted] of the DIRAN anti narcotics police detachment. “Everybody here does something.” Nor does Putumayo suffer from the same problem of internally displaced persons many other departments are experiencing; instead, Putumayo’s population is increasing. Many of its new residents have been attracted by promises of “easy money” in the coca boom. Many work on one of the many large plantation style coca farms in Putumayo which seem to be the norm rather than small plots planted by individual farmers… [The Samper Administration’s] three-year ban was designed to provide the locals time to transition out of coca, before the hammer of the state came down.

But it hasn’t worked that way. Instead, the state invested little in alternatives for Putumayo – and Putumayo used the three years to plant coca. Limited aerial fumigation began only in November 1999 in northern Putumayo, with NAS-contracted spray planes spraying as far as ten miles south of the Caqueta River separating Caqueta and Putumayo. With this month’s graduation from training of the army’s First Counter-Narcotics Battalion, more extensive spraying is expected to begin in early 2000 – although the national government is still quite concerned about the likelihood of social protest and an upswing in violence if Putumayo spraying begins in earnest.

Puerto Asis: A Snap-Shot of Life on the Front Lines

…

Both the DAS (FBI-equivalent) and the SIJIN investigative police have abandoned Puerto Asis in the past two years due to security concerns. The town’s mayor, Nestor Hernandez Iglesia, was placed under house arrest in October for fraudulent contracts and kickbacks…

Since November of 1998, 18 of the town’s 80 police have been killed. The DIRAN cops abandoned their unsecure base on the edge of town in favor of a downtown location after eight of their brethren were killed in a FARC bombing. Even more police have been assassinated since then, however, by the security forces’ biggest nightmare – the Urban Militia members of the FARC. Two DIRAN policemen were separately shot to death within eyesight of the new police station in broad daylight. A departmental policeman was killed just as a local elementary school disgorged its hundreds of students…

The security of Puerto Asis is “guaranteed” by 35 DIRAN anti-narcotics police (only two of whom are officers), plus 45 regular CNP. As of this summer, the town is also home to a company (100 men) of the Army’s 24th Brigade. The town has suffered four urban FARC attacks in 1999, although the FARC has thus far refrained from an outright “takeover” of the town – something the town’s defenders concede the FARC could do whenever they decide it is in their interest…

The Army company patrols town only as far as the river banks (3 km from downtown). While the Army and police sometimes mount random daytime roadblocks on the outskirts of town, neither will mount such roadblocks at night. Neither the cops nor the army venture across the river, where an estimated 500 FARC militia controlled the tin-roofed shacks and slums that dot the far side and are home to the bulk of the “urban” population. The police matter-of-factly concede that the FARC controls the river. Having bought several dozen outboard motorboats for local water taxi services, the FARC can “reclaim” the boats at will for use in conducting its own military or trafficking operations. On the other hand, the Navy is based in the far west of the department (Puerto Leguizamo) and has visited Puerto Asis -- the largest port on the Putumayo River-- just once this year…

Road travel outside of the town is dangerous. The guerrillas regularly mount roadblocks, even in the daytime, both north and south of the town. As a result, the security forces avoid inter-town travel by road. Neither the police nor the Army have any dedicated air assets in the department (much less in town), although the Ecopetrol state oil company provides the Army at Santa Ana (a 10 minute ride from Puerto Asis) 20 hours of MI-17 helicopter use per month. The nearest dedicated air support is one flight hour away at Tres Esqunias.

The Paramilitaries Have Arrived

Meanwhile, the AUC paramilitaries have come to Putumayo. Several locals, [deleted] told Poloffs that the AUC paramilitaries now control the urban areas of both Puerto Asis and La Hormiga, conducting daytime roving patrols in known vehicles. [One line deleted] stated that the FARC’s repression has prompted authentic popular rejection of the FARC and clear support for the paramilitaries. [Several lines deleted] complained to Poloffs that, in such an environment, the civilian populace do not report to the security forces on the paras’ activities.

Virtually all interlocutors dated the paras’ arrival in the department to early 1998. In phase one, the paras’ began a graffiti campaign announcing their arrival and sponsored a number of horrific massacres of unarmed individuals, allegedly campesino coca-growers, narcos or FARC supporters. All interlocutors noted, for example, that Puerto Asis has been "relatively quiet” after violence spiked in May-June this year. In this second phase, the paras let up on the violence, increased urban confidence, and began quietly schmoozing the department’s economic and political leaders and asking for money and support. In this manner, said one contact, the paras built up a local war chest while also building political legitimacy. The paras also entered a bidding war against the FARC; they offered their services to the narcos, undercutting the FARC on prices while promising increased public security.

[Several lines deleted] that the local AUC leadership is currently composed of individuals imported from Antioquia and elsewhere in northern Colombia. The rank and file, he said, are composed by more and more locals, as the AUC has tapped into legitimate anti-FARC resentments. He stated that the AUC's local chapter is now on its fourth commander in less than two years, with at least one of the previous commanders having been executed by his AUC superiors for killing the wrong people - people associated with the AUC’s narco-backers. (The FARC also reportedly executed one of their own deputy front commanders earlier this year for similar offenses.) Other interlocutors confirmed this, adding that the AUC’s command and control has improved greatly in recent months.

[Deleted] and other civilians all echoed the same theme: that the military and police were “complacent” about the AUC’s presence in the region. Many recognized that this was “understandable” given the FARC’s overwhelming pressure on the security forces. But they nonetheless worried that this “turning a blind eye” would only corrupt the public forces, given the AUC’s own narco-financing. Others volunteered that the civilians do not report paramilitary activities to the security forces because “no one sees the police and army as impartial.”

Some civilians said the “complacency” of the security forces often crosses into active complicity with paramilitaries. [Several lines deleted.]

DOCUMENT 8 [DOCUMENT 25]

The Rumsfeld Archive

In this “snowflake” memorandum, U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld proposes the creation of a military working group to set forth options for more aggressive U.S. interventions in Colombia in the event they were asked to do so by the Colombian government.[1]

I wonder if it might make some sense for SOUTHCOM and SOCOM to be tasked with establishing a joint working group to think through what we might do in Colombia if we are asked. It seems to me we would have to decide what victory would be, and then think through a plan to achieve what we decide to characterize as victory.

The group might be in contact with folks at CIA, DEA, Treasury and State, and also probably coordinate with Wayne Downing at NSC.

There is a lot of history in defeating insurgencies—in the Philippines from 1898-1902, in Nicaragua with the Marines in the 1920s, during the Greek civil war in the 1940s, in Malaysia in the 1950s and even in some pacification efforts in South Vietnam that worked during the 1960s and 1970s.

Certainly, if we end up doing something, it would fit into the nation-building category, which the administration has not favored. On the other hand, it could use the principles of entrepreneurial nation-building that Secretary O’Neill and others are beginning to develop.

The working group might want to talk to DARPA to see what programs are being developed for surveillance, intelligence, etc. that might be useful. They might also want to talk to Cebrowski on network-centric warfare as applied to jungles, urban areas and insurgencies.

I suspect this should be a very small cell that would report back to us in 90 days.

My view is that Colombia is a hard case, but, nonetheless, I think we ought to be seeing what, if anything, might be done.

Please let me know what you think.

DOCUMENT 9 [PLAN COLOMIA DOCUMENT 46]

FOIA

U.S. Southern Command’s Joint Intelligence Center compares the Colombian Army’s current Plan Patriota to Plan Lazo, the Colombian Army’s first major counterinsurgency campaign against FARC that ran from 1962-1966.

Then and Now:

- In 1959 and again in 1962, U.S. officials conducted survey of COLMIL counter-insurgency capabilities.

- Key findings included:

- Lack of central planning and coordination affecting counter-insurgency efforts at all levels

- Resource fragmentation requires logistical reform

- Insufficient communications, transportation, and equipment to prosecute coordinated and sustained operations

- Inadequate fusion and dissemination of intelligence at COLAR and national level hamper counterinsurgency effort

- Civic action and psychological operations must be continuous rather than sporadic

- Broad social, political, and economic problems exist and solutions appear remote

- Continued development of special counter-guerrilla teams from helicopters with emphasis on Lanceros will substantially reduce guerrillas within a year

COLMIL Campaign Plans Compared:

Plan Lazo, 1962-1966: five phased plan whose state primary objective was to eliminate the “independent republics” and destroy guerrilla-bandit groups.

- 1962, total estimated strength of guerrilla-bandit groups was approximately 8,500

- 1964, total estimated strength of guerrilla-bandit groups was approximately 2,000

- According to 1965 AMEMB [U.S. Embassy] cable, COLAR determined more aggressive action was necessary in one “communist” zone located in southern Tolima where a communist named “Tirofijo” Manunel Marulanda (a.k.a. Tirofijo) had been active in this zone and continues to sit atop the FARC

- 1966, violence levels significantly reduced by Plan Lazo stalls as elite interest wanes; U.S. became increasingly focused on conflict in Vietnam.

…

Plan Lazo Lessons Learned

[Two lines deleted]

- Civil affairs, civil defense, and counterinsurgency operations combined to deny widespread development of clandestine civilian infrastructure.

- [Two sub-points deleted]

- Attacking leadership of guerrilla-bandit gangs splintered organizational cohesion, resulting in a 20 percent increasing in enemy KIAs

- [Two sub-points deleted]

- Intelligence was a vital force multiplier, allowing security forces to deal with both mainline guerrilla units and their underground support structures

- [Two sub-points deleted]

- Counterinsurgency is a political strategy with a derivative military component; other components are political, economic, social

- [Two sub-points deleted]

DOCUMENT 10 [PLAN COLOMBIA ANNEX DOCUMENT 47]

FOIA

FOIA

In February 2004, DynCorp continued to support the Colombian Army’s Plan Patriota operations and supported a pair of high-profile HVT missions against FARC leadership. In the first case, DynCorp supported Operation Dignidad, a joint operation of the Colombia Army and Police aimed at seizing control of the town of Miraflores from the FARC.[2] DynCorp "aerial assets and personnel" were also "critical" to an HVT mission resulting in the capture of the FARC leader known as "Sonia" (“Omaira Rojas Cabrera”).

COLAR Program

Overall Rating: Excellent

Management: Excellent

The Contractor provided aerial, administrative, and maintenance support during February to FOB Tolemaida, FOL Tumaco and FOL Larandia. Additionally during February the Contractor provided aerial support to COLMIL's "Plan Patriota" missions to San Jose and Larandia. Contractor also provided aerial support to a temporary FOL in Neiva (for Medevac and mission support for the 9th Brigade). This last mission to Neiva was clearly beyond contractual requirements in that the Contractor's Operation Manager clearly used his experience and knowledge of the lack of pre-planning on the part of the Colombian Military to correctly foresee that complications would arise with this simple one day mission. This simple medevac mission grew into a much larger project and without the Contractor's Operations Manager foreseeing this possibility and correctly sending forward both operations and maintenance personnel along with the aircraft and flight crews this mission would not have ended successfully. Clearly the Contractor's Management Team sustained support well in excess of contractual requirements.

The Contractor's noted mission flexibility was again highlighted this month. The Contractor was able to sustain aerial support by providing a QRF (Quick Reaction Force) that included slick aircraft, gun ships, and a Command and Control aircraft directly in support of ERADICATION spray efforts in the departments of Narino and Caqueta while continuing to provide aircraft for troop movements and re-supply efforts in direct support of the Counter Drug Brigade.

The Contractor continued to provide outstanding logistical and planning support with movements of FARP's from one location to another rapidly. With the culmination of a HVT target near Mitu, all equipment, including FARP [Forward Arming and Refueling Point] equipment and maintenance equipment was quickly reassembled in Larandia for the next HVT target. Clearly the Contractor's logistical section is providing outstanding support.

The Contractor continued to support CD Brigade missions in Tumaco and Larandia as Contractor was tasked with providing aerial assets and personnel for Operation Dignity near San Jose, Miraflores, and Mitu. Contractor's efforts paid off in the mission's successful culmination.

The Contractor also provided outstanding support to the Colombian Army during a second HVT mission in the same month. Their efforts in providing aerial assets and personnel were critical in the successful termination of this mission in capturing "Sonja".

Manpower Utilization: Excellent

During February the Contractor moved personnel and aerial assets to Larandia from Tolemaida and Tumaco in direct support of 2 separate HVT missions, in addition to supporting a high visibility mission to Neiva. All this was conducted while supporting requirements [of] the FOB in Tolemaida, and the FOLs located in Tumaco, Larandia, and San Jose. This support was well beyond contract requirements.

…

Operations: Excellent

Operations Planning: Excellent

The Contractor's vast experience in the coordination of Air Assault operations was used successfully in the planning and implementation of operations San Jose, Calamar, Miraflores, and Mitu in direct support of COLMIL's "Plan Patriota." Their planning and coordination efforts included the movement of aircraft, personnel and equipment from several locations to accommodate the mission out of San Jose and Larandia. These efforts led to several successful and safe missions.

Training and mentorship has [sic] aided in producing quality officers in COLAR. One such example is [deleted] who was instrumental in the successful completion of the HVT mission in Larandia against “Sonya”. His actions in planning and using forethought in mission planning, successfully avoided major problems during this mission, and is further evidence of progress towards nationalization.

DOCUMENT 11 [PARAMILITARY ANNEX DOCUMENT 02]

FOIA

The U.S. Embassy finds that anti-guerrilla “vigilante bands” in the Magdalena Medio are also “used to drive peasants off the land.” With the support and cooperation of the Army, especially the 14th Brigade in Cimitarra, “heavily armed” ranchers were driving out insurgents while also “seizing the opportunity thus afforded to aggrandize their economical and political power in the area.”

The large Mid-Magdalena (Magdalena Medio) area in Central Colombia, which has had a lengthy history of violence, is currently experiencing a reign of terror. Local ranchers have organized vigilante bands which have been responsible for several hundred deaths over the last year and driven thousands from their homes. Ostensibly the vigilantes aim to eliminate guerrillas and sympathizers of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), which have long infested the region. There are indications, however, that the vigilante groups have also been used to drive peasants off the land, permitting the major ranchers to consolidate and expand their landholdings. Army units are actively cooperating with the vigilantes, and the FARC seems to be on the defensive. Alarmed by the situation, the GOC [Government of Colombia] has appointed a high commissioner for the area and proposed creation of a Mid-Magdalena Regional Autonomous Corporation with a funding of U.S. Dols 50 million, but its plans to address the root cause of the violence, the inequitable distribution of land, so are insufficient. Nationally, the Mid-Magdalena violence is having serious political repercussions for President Betancur and his administration, while locally the violence has badly disrupted the region’s political and economic life. So long as the Mid-Magdalena and similar areas lie beyond the effective control of the GOC, and the grievances of the campesinos are not adequately addressed, guerrilla insurgency and rural violence in Colombia will continue.

…

The reign of terror has proceeded largely unimpeded because the security forces in the region deliberately have not interfered with the vigilante bands. These forces consist of (1) the Colombian Army’s XIV Brigade, established in April 1983 and headquartered in Cimitarra, which is comprised of three infantry battalions, an engineer battalion and a service battalion (with a total of 3,000-4,000 men), and (2) a police company of police carabineros (about 100 persons). The Colombian Navy also has small patrol boats on the Magdalena River. According to an Army source, even 20 battalions could not patrol the area adequately.

…

Meantime, as reported by the Embassy’s defense attache in June 1983, the Colombian Army’s XIV Brigade has had some success against the FARC in recent months. The ranchers and the Army are actively cooperating with each other against the guerrillas, and the Army no longer is penalizing the campesinos for having cooperated with the FARC. The remoteness, size and the Army’s lack of mobility have seriously hampered the Army’s operations, however. That the FARC in the region is being pressed between the Army and the vigilante groups is evidenced by public calls in the latter part of August from FARC and Communist Party spokesmen for a cease-fire in the Mid-Magdalena. However, the Embassy has information that the FARC guerrilla simply moved to more outlying areas when the Army moved in, and that the FARC continues to conduct operations in the Mid-Magdalena.

COMMENT: While the exact situation at present in the Mid-Magdalena is confused and in flux, what does seem clear is that the local ranchers, heavily armed since the end of last year, have been waging an all-out bloody war against the FARC and anyone thought to be sympathetic to it, that the Colombian Armed Forces are cooperating with the ranchers against the FARC, and that the resulting violence has caused thousands of campesinos, ground between the FARC and its enemies, to flee the area.

What is less clear is exactly what is happening to the campesinos… According to information recently obtained by the defense attache, some Army units operating in the Mid-Magdalena may have (illegally) accepted payments from vigilante groups… It seems likely that the ranchers, via their vigilantes, are not only seeking to eliminate their old enemies, the Communist guerrillas and their allies, with the full and active support of the Army, but are seizing the opportunity thus afforded to aggrandize their economical and political power in the area. The defense attache has reported that the Army is fearful that the vigilantes may turn on the Army if and when their common enemy—the FARC—is defeated. Thus the present Mid-Magdalena turmoil appears to be in part the latest chapter in an old history of class warfare between landholders and peasants in the area.

DOCUMENT 12 [PARAMILITARY ANNEX DOCUMENT 04]

FOIA

A CIA report finds that much of the recent violence against “suspected leftists and communists” in Medellín and Urabá was the result of Colombian Army intelligence B-2 detachments from the 4th and 10th brigades working in coordination with narcotraffickers and paramilitary groups. The reporting officer said it was “unlikely” such coordination took place “without the knowledge of the Fourth Brigade commander.” In a separate section, the report indicates that the Honduras and La Negra killings were the result of coordination between the B-2 intelligence unit of the 10th Brigade and “an unidentified private right-wing paramilitary group.”

A wave of assassinations against suspected leftists and communists in Medellin throughout 1987 were the result of a joint effort between the intelligence chief (B-2) of the Colombian Army Fourth Brigade in Medellin, Ltc. Plinio ((Correa)), and unidentified members of the Medellin narcotics trafficking cartel. ([Deleted] Comment: The deaths include the killing of several Patriotic Union (UP) members. It is unlikely that any cooperation between the B-2 and Medellin Cartel in carrying out assassinations of suspected leftists and communists could have taken place without the knowledge of the Fourth Brigade commander.) …

…

The individuals who executed 20 banana plantation workers on 4 March 1988 obtained the names of their intended targets from the Colombian Army’s Tenth Brigade intelligence unit (B-2). The B-2 obtained the names in January 1988 during the interrogation of a Popular Liberation Army (EPL) member, alias “Augusto.” “Augusto” and two other EPL members, all belonging to an EPL unit led by alias “Rambo” were captured by the Colombian Army at the town of El Totumo near the eastern shore of the Gulf of Uraba. During his interrogation by the B-2, “Augusto” provided the names of various EPL members and sympathizers, many of whom belonged to the banana workers union “Sintagro” in Uraba. The information from “Augusto” was provided to members of an unidentified private right-wing paramilitary group. ([Deleted] Comment: The victims of the 4 March killings were EPL and ‘Popular Front’ sympathizers and members of Sintagro, all of whose names appeared on the B-2’s interrogation reports. Prior to the killings, they were accurately identified by their attackers from a list which the attackers possessed.)

([Deleted] Comment: While it is possible that some of the individuals who conducted the killings are active members of the Tenth Brigade’s B-2, it is more likely that the intelligence information was shared with a private paramilitary group in order to provide a cutout to avoid blame on the Colombian military. Although the Colombian military prefers to blame the killings on rivalry between the EPL and the [FARC], the killers’ modus operandi showed a lack of knowledge of guerrilla ideology, disproving FARC involvement.)

DOCUMENT 13 [PEPES ANNEX DOCUMENT 10]

Mark Bowden

Just a few months after the killing of Escobar, DEA officials traveled to Bogotá to meet with DEA and CNP officials from the Medellín Task Force to get a clearer understanding of “the Medellin Cartel’s past, present and future.” The report reviews the narcotrafficking landscape in Colombia after the fall of Escobar, focusing on individuals and organizations well positioned to take advantage of the power vacuum. These include members of “El Grupo”—Gustavo Tapias (“Techo”), Juan Arango, and Guillermo Angel Restrepo—and Antonio Bermudez (“El Arquitecto”), who went on to become a key intermediary in Mexico for Norte del Valle Cartel leader Luis Hernando Gómez Bustamante (“Rasguño”).

… The purpose of these meetings was threefold: 1) to discuss the current state of the Medellin Cartel; 2) to examine the near-term and long-term potential for future operations by the Medellin Cartel trafficking groups; and 3) to consider the CNP commitment to continue operations against the Medellin Cartel…

…

A Historical View of the Medellin Cartel

…

… By the late 1980s, Pablo ESCOBAR was waging war with the GOC [Colombian government] , the AUTODEFENSAS, (a Medellin based self defense force) and the Cali Cartel. To wage this war, ESCOBAR collected a “war tax” from traffickers who operated from Medellin. The “war tax” was a percentage of the value of the cocaine each trafficker shipped. As ESCOBAR became more preoccupied with the violence, the Medellin Cartel began to lose its share of U.S. cocaine markets to the Cali Cartel.

…

The clandestine cocaine labs which supplied ESCOBAR and the OCHOAs have not stopped their business solely because ESCOBAR is dead—just as business did not cease when Gustavo GAVIRIA and Jose Gonzalo RODRIGUEZ-Gacha were killed. The remaining Medellin Cartel traffickers will continue their respective trades whether operating labs, transporting cocaine or laundering money. The questions which remain are who will they support with their services and which groups will emerge as Medellin’s major trafficking organizations.

…

Current Organizations:

Several major traffickers, with ties to Medellin, currently are in operation… The major Medellin traffickers who have continued to operate and who pose a significant threat to in the future are:

Jorge Luis OCHOA and his brothers…are incarcerated in Itagui Prison… Intelligence indicates the OCHOAs still have a hand in cocaine shipments…

Leonidas VARGAS-Vargas, according to LTC [Norberto] Pelaez, is virtually free to run his business even though he has been in prison since January 1993. VARGAS-Vargas, was a cocaine conversion laboratory operator who worked for Jose Gonzalo RODRIGUEZ-Gacha. Leonidas VARGAS learned the cocaine business well during the years he workd with RODRIGUEZ-Gacha. VARGAS-Vargas was intimately involved in the production and transportation of cocaine HCl. Following RODRIGUEZ-Gacha’s death in December 1989, VARGAS-Vargas rose in power within the Medellin Cartel. VARGAS-Vargas was a major owner and supplier of 23 tons of cocaine seized in Monteria, CB between February and April 1991. Pablo Escobar described Leonidad VARGAS-Vargas as one of his most trusted lieutenants. Today, VARGAS-Vargas is known to control cocaine shipments and to own two air cargo companies which are used to ship cocaine.

Luis Enrique RAMIREZ-Murillo… During the hunt for Pablo ESCOBAR, RAMIREZ provided information against ESCOBAR to the Fiscalia. On February 17, 1994, Mickey RAMIREZ met with S/As [Special Agents] Pena and Murphy and S/C [Barry] Abbott to discuss RAMIREZ cooperation with DEA. RAMIREZ was asked if the ESCOBAR organization was dead. RAMIREZ replied “no” and said that Jose Fernando POSADA-Fiero and Oscar ALZATE-Urquijo AKA ARETE would take control of the remnants of Pablo ESCOBAR’s organization…

Four significant Medellin traffickers who are known as “EL GRUPO” continue to operate in Medellin, CB. “EL GRUPO” consists of Gustavo TAPIAS AKA TECHO; Guillermo BLANDON AKA William; Juan ARANGO; and Guillermo ANGEL-RESTREPO. The members of “EL GRUPO” split with ESCOBAR and joined forces with the Cali Cartel after ESCOBAR murdered the MONCADA and GALEANO brothers. During the hunt for Pablo ESCOBAR, “EL GRUPO” provided information to the CNP and DEA. However, “El GRUPO” has not retired from the cocaine trade as is evidenced by the September 1993 CNP raids against the Jose Guillermo GALLON organization. The GALLON organization took its orders from Guillermo BLANDON. Subsequent to the GALLON raids BLANDON was murdered in November 1993. Now that ESCOBAR is dead, the members of EL GRUPO are free to expand their businesses.

The MONCADA and GALEANO Families…

Antonio BERMUDEZ-Uribe [sic] AKA El Arquitecto was first identified as a major Colombian trafficker who coordinated the transportation of cocaine from Colombia to the United States via Mexico and the movement of drug proceeds from the United States to Colombia. In July 1992, BERMUDEZ and his Mexico City based lieutenants negotiated with a DEA C/I [Cooperating Individual] to coordinate the shipment of forty tons of cocaine from Colombia through Mexico to the United States. At that time, BERMUDEZ was coordinating the shipment of this and other cocaine shipments for Pablo ESCOBAR and the OCHOA brothers through ESCOBAR’s lieutenant, Jose CORREA, AKA OREJAS. When OREJAS was killed, BERMUDEZ returned to Medellin and assumed CORREA’s position. Although the investigation of BERMUDEZ’ organization in Mexico has resulted in large cocaine seizures and the arrests of key organization members, BERMUDEZ immediately reorganized and continues to transport cocaine through Mexico using an alternate Mexican organization. Intelligence indicates that BERMUDEZ may be establishing a cocaine conversion laboratory. Intelligence has also linked BERMUDEZ to financial assets in the United States, Mexico, Colombia and Ecuador. DEA Bogota CO reporting indicates that BERMUDEZ has become one of the most important Medellin Cartel that BERMUDEZ has become one of the most important Medellin Cartel traffickers in the aftermath of Pablo ESCOBAR’s death.

…

The Present State of the CNP Medellin Task Force:

In response to ESCOBAR’s escape in July 1992, the GOC created the Medellin Task Force to capture ESCOBAR and dismantle the Medellin Cartel. The Task Force focused on Pablo ESCOBAR his immediate organization. Since ESCOBAR’s death, the primary focus of the task force has centered on the remaining members of the Medellin cartel as well as the up and comers who have begun to operate in Medellin.

LTC Pelaez believes the Medellin Cartel must be watched; although the Cartel may be in a state of turmoil at the present time, they will soon begin to reorganize and within a shoert time could be very powerful… The GOC and the CNP recognize the need for continued vigilance toward Medellin and demonstrate their commitment to pursuing the Medellin Cartel through their continued support of the Medellin Task Force. The Medellin Task Force has an assigned strength of 311 officers, 250 uniformed officers and 61 intelligence agents. Additionally, the Medellin Task Force has considerable technical intelligence gathering capability permanently assigned.

Conclusions:

The Medellin Cartel will reorganize and rebuild; opportunities exist for the growth of both large and small Medellin trafficking organizations. While things may have slowed temporarily, it is only a matter of time until it is once again business as usual. With ESCOBAR gone and his organization in chaos, there are many other Medellin based traffickers who are looking for new contacts and business deals. The opportunities for traffickers in Medellin might be compared to the business/investment opportunities in Russia after the fall of communism and the break-up of the Soviet Union.

…

Presently, a few Medellin trafficking organizations are capable of sending multi-ton quantities of cocaine to the United States and are not out of business as was thought or hoped for by some optimists. The number of Medellin organizations capable of sending multi-ton cocaine shipments is expected to increase.

The Medellin situation requires continued observation and strong enforcement operations to keep the growth in check. If DEA and the GOC turn their backs on Medellin, in a short time, the problem will once again be out of control.

DOCUMENT 14 [CHIQUITA ANNEX DOCUMENT 01]

FOIA

This fascinating document from Chiquita’s security office in Colombia captures its view of the conflict in Urabá and describes the nature of the company’s relationship with each of the armed actors. Of special interest is Chiquita’s description of its links to Esperanza, Paz y Libertad, a group of demobilized guerrillas from the Ejército Popular de Liberación (EPL) insurgent group. The former guerrillas and their new “armed wing,” the Comandos Populares, were now widely seen as “on the side of the government” and something more akin to a right-wing paramilitary group. The report also highlights the links between the conflict and Chiquita’s labor issues, as union representatives sympathetic to Esperanza had signed a labor agreement desirable to the company, breaking with union members seen as sympathetic to the Coordinadora Guerrillera Simón Bolívar (CGSB), the objective of which was “to destabilize the Zone at any cost; to gain complete political and territorial control.”

El siguiente es un informe preparado por P.I. en el cual se hace un recuento general sobre la situación de orden publico en Uraba; los grupos guerrilleros que tienen incidencia en la Zona, la posición de COMPANIA FRUTERA DE SEVILLA con respecto a cada uno de los grupos y las posibilidades para los próximos meses de 1992.

…

- EJERCITO DE LIBERACION POPULAR EPL

…

ESPERANZA PAZ Y LIBERTAD empezó a ser víctima de las acciones bélicas y de exterminio generadas por sus antiguos compañeros, que los obligo a crear un brazo armado autodenominado los COMANDOS POPULARES CP. Y se genero una purga de parte y parte.

Teniendo en cuenta que el CP que entre comillas esta de parte del Gobierno, logro algún concepto bueno del Ejército, que en ocasiones les permite su “libre” movilización por la Zona. Esto no ha sido bien visto por los otros grupos insurgentes que junto con los CARABALLISTA hacen parte integral de la COORDINADORA GUERRILLLERA SIMON BOLIVAR; y han manifestado que lo que antes ellos veían como una disputa entre un group Paramilitar el CP apoyado por el Ejército y un miembro de la CGSB.

Esto obligo a que ESPERANZA PAZ Y LIBERTAD modificara su planes de ofensiva y las ayudas se canalizaran a través de AUGURA como agremiación que reúne a los Bananeros de Uraba; específicamente haciendo consignaciones en una cuenta corriente de un banco de Apartado.

La modalidad de operar de el CP es la misma que como cuando ellos hacían parte de el grupo Guerrillero; esto es mediante amenazas, intimidaciones, chantajes, etc. Mas sin embargo la queja de alguna Bananeros hecha a AUGURA, como en nuestro caso logro que la presión bajara y cambiaran los términos. No obstante pedidos de poca monta para mercados, drogas, botas, munición, etc.

…

COMENTARIOS GENERALES

…

El paro que se genero por los acuerdos con el INSTITUTO DE SEGUROS SOCIALES en las Fincas del Grupo Banazuñiga que comercializa la fruta con C.I. BANADEX; y la posterior solidarización de el resto de Grupos o Fincas que exportan la fruta con la misma comercializadora; genero un acuerdo político.

…

A ultimo momento el acuerdo fue firmado por el [deleted] como único representante de BANADEX y los representantes del sindicato simpatizantes de ESPERANZA PAZ Y LIBERTAD; por el contrario el Sr. [deleted] quien es firme aliado de las FARC influyo para que los demás miembros que simpatizan con la COORDINADORA GUERRILLERA SIMON BOLIVAR se abstuvieran también de firmarlos.

…

El sindicato en este momento esta fuertemente dividido entre las personas que firmaron el acuerdo, y las que lo rechazaron.

…

La no firma del acuerdo, y la intransigente posición de la CGSB hacen preveer [sic] que la orden impartida por el Comando Central de esa agrupación Guerrillera, es la de desestabilizar la Zona a costa de cualquier precio; para lograr el completo control político y territorial.

DOCUMENT 15 [PARAMILITARY ANNEX DOCUMENT 39]

FOIA appeal

This is the second in a series of reports about the U.S. Embassy Political Officer’s (“Poloff”) information-gathering visit to “the baseball-playing, cattle-raising and cotton-growing town of Monteria” in Córdoba Department, calling it “perhaps the most solidly pro-paramilitary burg in all of Colombia.”

Summary: During a recent Poloff trip to the openly pro-paramilitary town of Monteria (Cordoba Department), Colombian ranchers, businessmen, academics and other explained to Poloff how the local “Self-Defense Forces of Cordoba and Uraba”…were originally established during the 1980s, with the assistance of the Army and Police, as a reaction to years of unchecked guerrilla depredations… Poloff also learned something of the paramilitaries’ international ties – including allegations of having received material assistance from U.S. and other foreign multinationals, and training by foreign mercenaries… A number of interlocutors advocated that “The Cordoba Model” be adopted by Colombia nationwide…

…

Cordoba, Yesterday….

[Deleted] that the Colombian Army helped establish the local paramilitary structure (what became the ACCU) in the late 1980s and early 1990s, supplying training, weapons and ammunition, as well as logistical and intelligence support. But the real change, [deleted] argued, came in the early 1990s, when the Army augmented the local military presence from a battalion to a brigade (the 11th Brigade), after the killing of Colonel Diaz, the battalion’s commander. The local private sector, he recounted, bought land, tools, vehicles, and gas, and paid the salaries for counter-guerrilla Police and Army units to be deployed. The Police, the Army’s First Mobile Brigade, and the paramilitaries then pushed south across the department, in a very coordinated fashion. After the Army moved through, the Police and paramilitaries established permanent outposts.

…

The 1990-92 war against the EPL came “at a very high social cost”, [deleted] “with lots of deaths and human rights violations on all sides…” On its own initiative, the Cordoba Ranchers Association (“FEGACOR”), through the Foundation for Peace in Cordoba (“FUNPAZCOR”), freely provided 10,000 hectares of farm and cattle-grazing lands to the “resinserted’ EPL. Where are they now?, asked Poloff. Some are now in the Police and some are in the Army; others have joined the paramilitaries. Still others are farmers, cattlemen or have gone into private in various parts of the department. Most recently, another 225 EPL “dissidents” surrendered – not to the government, but directly to [deleted] – in early 1998.

…

The Paras’ International Ties

The paramilitaries have allegedly received material, training and ideological support from a variety of foreign sources, including Americans. [Deleted] noted that, while much attention has been focused on training provided in the late 1980s/early 1990s by [three lines deleted], there have been several “more important” rounds of foreign training since then. Two other Israeli teams have trained the paramilitaries in the past few years, he said, as had a team led by a retired French Army general…

…

Pablo Escobar and the Narco Wars

Poloff was a fly on the wall for a surreal encounter over scrambled eggs and fried plantains, with [two lines deleted] the three reminisced about past battles, swapping “war stories” (literally), and, from their various perspectives, attempting to educate Poloff about the history of the local conflicts and the role of narcotics in those conflicts.

The guerrilla war in Cordoba facilitated the arrival of narco-traffickers to the region. As the guerrilla violence increased in the late 1980s and early ‘90s, local farmers and ranchers abandoned the area in droves, selling cheap to rich narcos who were all too happy to legitimize themselves, in the Colombian tradition, by becoming large landowners. The Ochoa family bought extensive land-holdings and other investments in the area, as did rancher and narco Fidel Castano (the older brother, now generally presumed dead, of ACCU’s Carlos Castano).

…

… Fidel Castano, after having, beaten the EPL, had 2,000 paramilitaries working for him in the Cordoba and Uraba regions. Saying “enough is enough,” he turned his sights against Pablo Escobar, his former narco-associate, and became the military leader of “The Pepes”, “Those Persecuted by Pablo Escobar”. (Younger brother Carlos – now head of the ACCU – served as “Pepes” chief of intelligence.) “Everyone worked with the Pepes,” the three told Poloff, “the Auto-defensas, the Police, the Army, the DEA, two mercenaries recruited via ‘Soldier of Forture’ magazine, everyone.” Fidel Castano turned Escobar’s rules against him, declaring a moratorium on assistance to Escobar. “Anyone who pays taxes to Escobar, I kill.” He then proceeded to do so. With the assistance of the Police, Fidel wiped out all the Escobar-related narcos in Monteria and Cordoba.

Acknowledgement