Washington, D.C., August 13, 2018 – U.S. Cyber Command’s strategy for curtailing ISIL’s ability to exploit the internet may at least partially be paying off, according to an analysis of recently declassified documents posted today by the nongovernmental National Security Archive.

The new documents, obtained under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) by Motherboard and the Archive, center around Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY, a USCYBERCOM activity authorized in late 2016 to deny the Islamic State use of the internet.

Correlating new information in the records with the results of public academic research allows for at least a partial, preliminary judgment about the operation’s success. Notably, research from the George Washington University Program on Extremism shows a sizable downtick in ISIL’s use of social media that tracks with the timing of GLOWING SYMPHONY’s launch.

While substantially redacted, the records offer other research benefits. For instance, they make it possible to trace the evolution of the mission from broad concept to a complete plan of operations and authorization. One overarching conclusion from this is that cyber may not be revolutionizing operational planning as much as is often assumed.

At the same time, the execution and impact of counter-terror operations in cyberspace, as evidenced in these documents, speaks to the ways cyber is changing both how terrorist groups conduct global operations and how sophisticated responses are becoming more lethal by integrating cyber with precision-strike tactics.

Joint Task Force ARES and Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY:

Cyber Command’s Internet War Against ISIL

By Michael Martelle

In April 2017 USSTRATCOM released partially redacted versions of Task Order 16-0063 and Fragmentary Orders 01 and 02, dating from May through June 2016, which ordered the establishment of a task force to counter ISIL in cyberspace. The declassifications were in response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request by the National Security Archive’s Cyber Vault prompted by a July 15, 2016 Washington Post report by Ellen Nakashima and Missy Ryan. The references in this TASKORD informed follow-on FOIA requests, which produced a Mission Analysis Brief. These documents provide a small look into how the United States Military organizes capabilities for offensive cyber missions.

Our earlier analysis of the TASKORD in particular highlights the following insights:

- The mission guiding the formation of JTF-Ares aligns with the fourth strategic goal in the Department of Defense’s Cyber Strategy to “build and maintain viable cyber options and plan to use those options to control conflict escalation and to shape the conflict environment at all stages. […] If directed, DoD should be able to use cyber operations to disrupt an adversary’s command and control networks, military-related critical infrastructure, and weapons capabilities.”

- Cyberspace operators were tasked with coordinating not only with each other, but also with units acting in other domains (including locating targets for “lethal fires”) as well as intelligence agencies.

- Command and control of JTF-Ares was given to the commander of Cyber Command instead of Central Command or even Operation Inherent Resolve. This suggests that JTF-Ares has the capacity to operate globally against ISIL.

Further reporting by Nakashima in May 2017 shed light on the operation assigned to JTF-Ares, named Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY, which confirmed our analysis that JTF-Ares was operating globally both in and beyond the Iraq/Syria area of operations (AO). Nakashima’s report revealed that the global nature of Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY had presented political issues for policymakers in cases where ISIL content and capabilities resided or depended on infrastructure in a number of countries including US allies.

The definitional distinction between a task force and an operation is key to understanding the continuity of these documents.

- A Task Force is a component, or collection of units, within a force organized for a specific task or tasks. A Joint Task Force is a task force drawn from multiple military branches. While it is usually purpose-built, it does not in and of itself include authorization for action.

- An Operation is a series of actions organized around a unified purpose or mission.

The revelation of Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY led to a series of FOIA campaigns and the first success was released by Joseph Cox of Motherboard. These documents have been added to the Cyber Vault, and together with the previous releases on JTF-Ares paint a more complete picture of the US Military planning process as it relates to cyber operations.

Today’s posting will use these documents to guide readers through the Joint Planning Process from broad mission concept to the formation of the joint task force to an actionable operation plan and order.

The following section presents a Timeline of the documents that have recently been made public through FOIA. (The first two items on the list have been identified from footnotes in other records, and requests filed for their release.) Within the Timeline are descriptions of each document as well as excerpts of selected items. Clicking on the title of each record will access the entire document.

Timeline

2014-10-17

EXORD (Execute Order) issued for Operation Inherent Resolve

2015-03-29

2016-04-12

Mission Analysis Brief: Cyber Support to Counter ISIL

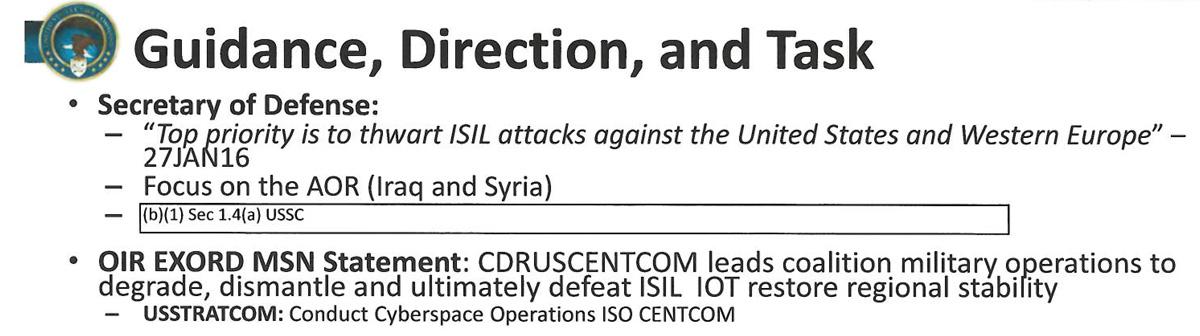

This USCYBERCOM briefing dated April 2016, more than a year after the order to provide cyber support to Operation Inherent Resolve, provides a very general concept of the mission to counter ISIL in cyberspace. The briefing makes early mention of Operation Inherent Resolve’s tasks and priorities before broadly outlining the role of USCYBERCOM within that mission:

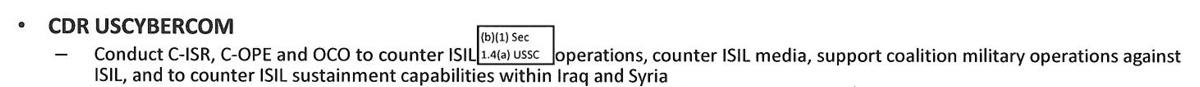

While this briefing emphasizes operations within Iraq and Syria, it is clear that planners are concerned with ISIL’s use of cyberspace to enable global terrorist networking and operations. Use of social media to incite lone-wolf attacks, online distribution of propaganda, and doxing (the publishing of an individual’s identifying information in order to harm or enable others to harm that individual) are all specifically mentioned.

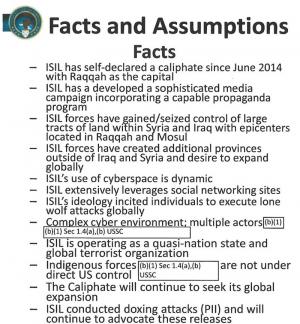

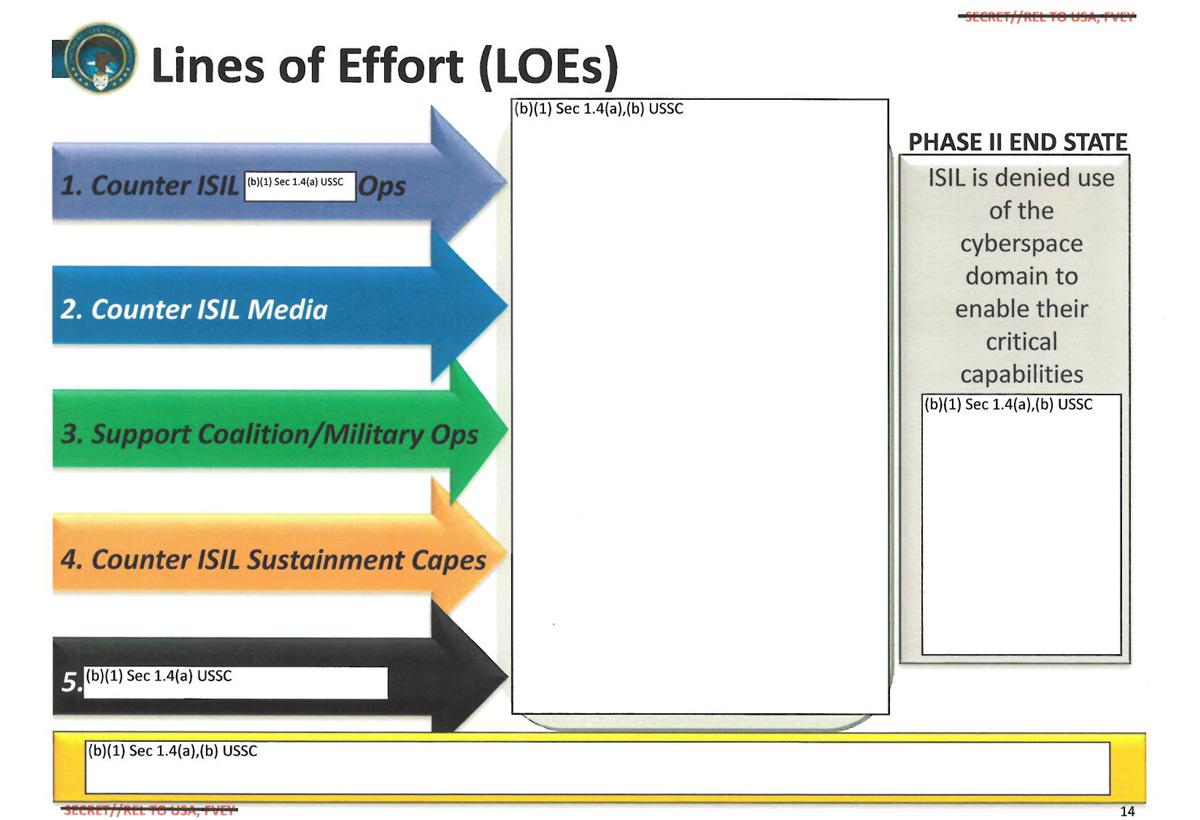

The briefing then delivers two standard elements of mission analysis: Commander’s Intent and Lines of Effort:

AOR – Area of Operations

IOT – In Order To

ISO – In Support Of

C-ISR – Cyber Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance

C-OPE – Cyber Operational Preparation of the Environment

OCO – Offensive Cyberspace Operations

The “next step” in the mission is then outlined:

2016-05-05

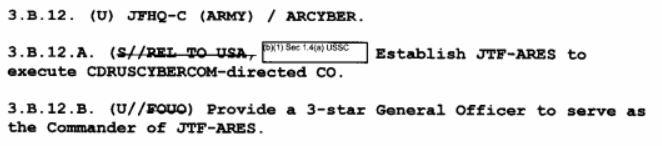

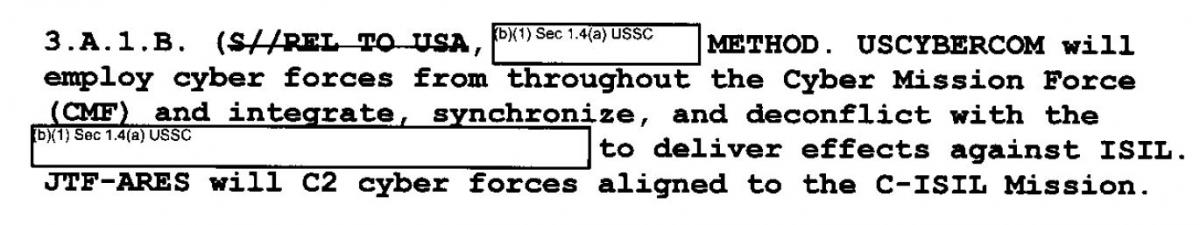

This document, amended by 2 Fragmentary Orders, orders the formation of JTF-Ares with the mission of developing and using malware and other cyber-tools to damage and destroy ISIL networks, computers, and mobile phones. They also give JTF-Ares instructions to coordinate and deconflict with friendly forces and intelligence bodies, but do not place limits on pursuing and attacking ISIL networks and hardware globally.

Command of JTF-Ares is given to an unspecified three-star general from Army Cyber Command. The only three star in Army Cyber is Army Cyber's commander, and reporting by The Washington Post's Nakashima confirms that at the time JTF-Ares was led by then-head of US Army Cyber (and current head of the NSA and USCYBERCOM) General Paul Nakasone.

Instructions are given to JTF-Ares to coordinate and deconflict with:

The broader counter-ISIL mission:

US Central Command and Special Operations Command:

As well as a name-redacted intelligence entity:

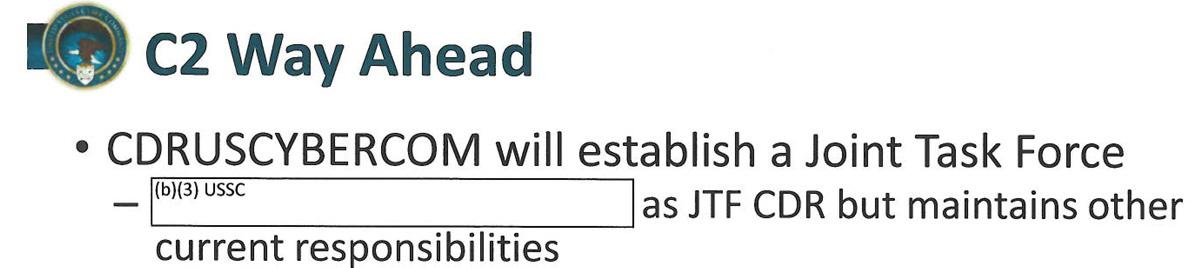

Command and control of JTF-Ares is given to the commander of USCYBERCOM instead of Central Command or even Operation Inherent Resolve.

2016-05-05

The unit established by this order and the next (FRAGORD 02), the subject of an article in the Washington Post, was assigned the mission of developing malware and other cyber-tools in order to escalate operations to damage and destroy ISIL networks, computers, and mobile phones.

2016-06-13

This order, along with FRAGORD 01, established a unit assigned to develop malware and other cyber-tools aimed at disabling ISIL electronic, computer, and communications equipment.

2016-09-12

Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY Concept of Operations

This Concept of Operations, or CONOP, follows a standard format and builds on themes developed in previous documents. At this stage in the process, planners have begun to specifically codify both the goals of the operation and the manner in which progress and success will be evaluated. Key elements introduced in the “execution” section of this document, though largely redacted, are Measures of Performance (MOP), Measures of Effectiveness (MOE), indicators, intended effects, and objectives.

An interesting aspect of the “execution” section is a sub-section on the coordination of “fires”.

While it appears as if cyber effects are being coordinated with artillery and airstrikes, this section is in fact an illustration of how the US Military presently conceptualizes offensive cyber effects. In Joint Publication 3-09 Joint Fire Support, effects in cyberspace are defined as a form of fire support. This section of the Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY CONOP illustrates how missions in cyberspace are coordinated in a manner analogous to artillery or airstrikes.

2016-09-16

Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY Overview (No Date, listed current as of September 16, 2016

This heavily redacted briefing provided an overview of Operation Glowing Symphony.

2016-10-07

In Progress Review – Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY

This briefing serves as a progress report for the planning of Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY, and was released with heavy redactions. Nonetheless, there are some key points of interest included at stage of the planning process which reveal how several issues were framed or modeled for the purpose of operational planning:

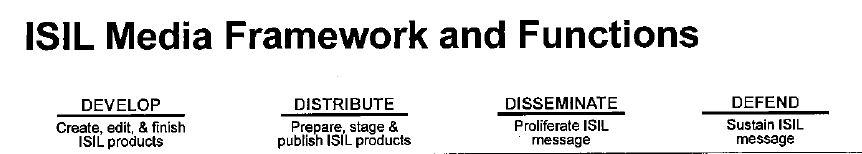

A four-part model of ISIL’s use of the media

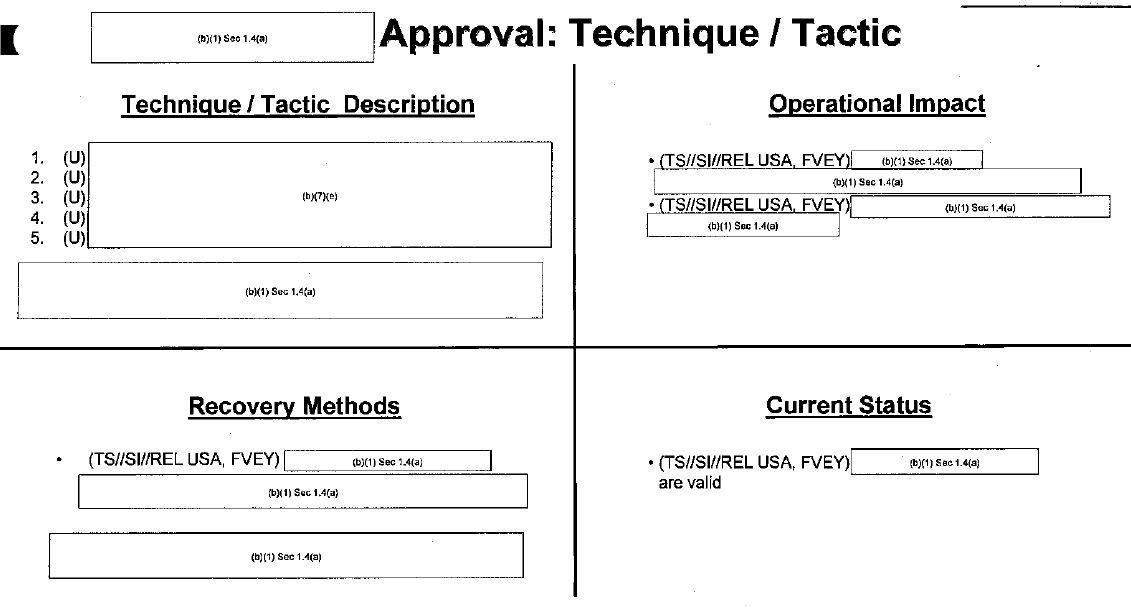

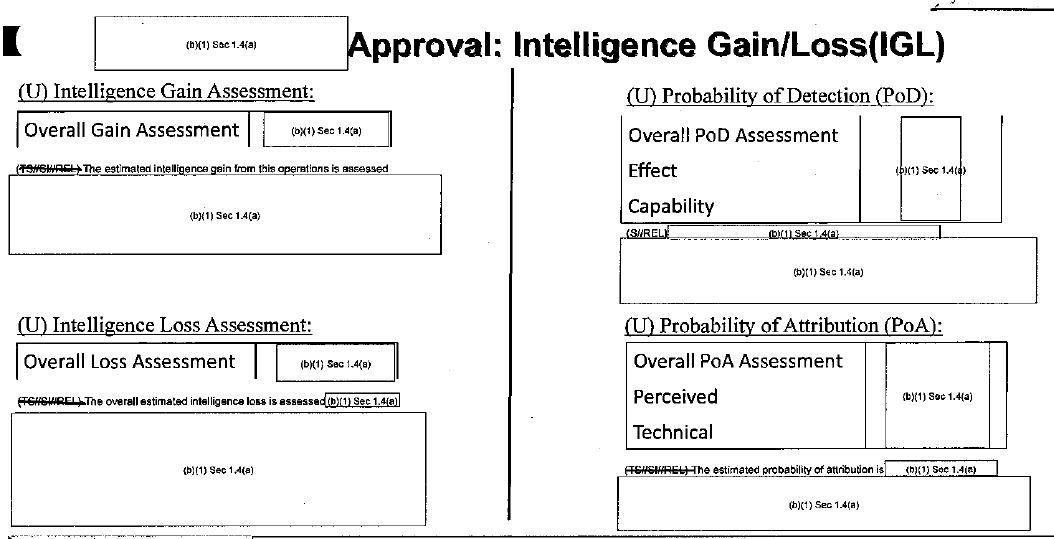

Considerations for a technique or tactic to be approved

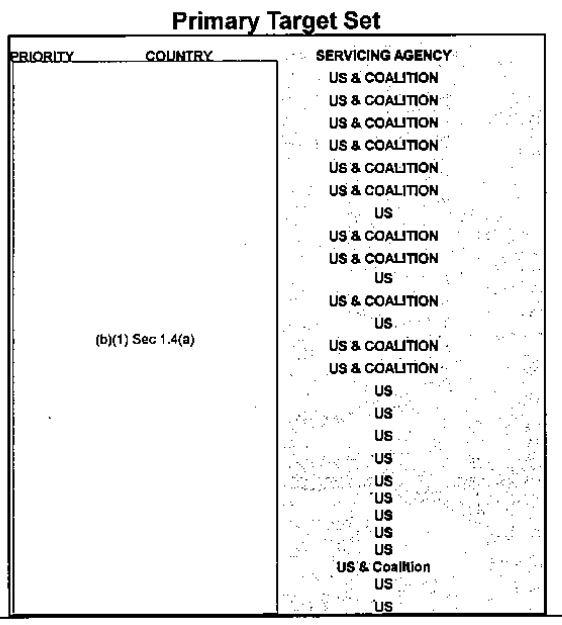

Finally, the briefing includes a redacted set of target priorities which reveals only the participation of coalition agencies in “servicing” targets.

2016-11-04

Agreed Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY Notification Plan

This document, redacted almost entirely, reveals only that Israel and The Netherlands played some unknown role in Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY which warranted the listing of their respective POCs (points of contact) at the bottom of each page.

2016-11-07

C-2 Mission Checklist – Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY

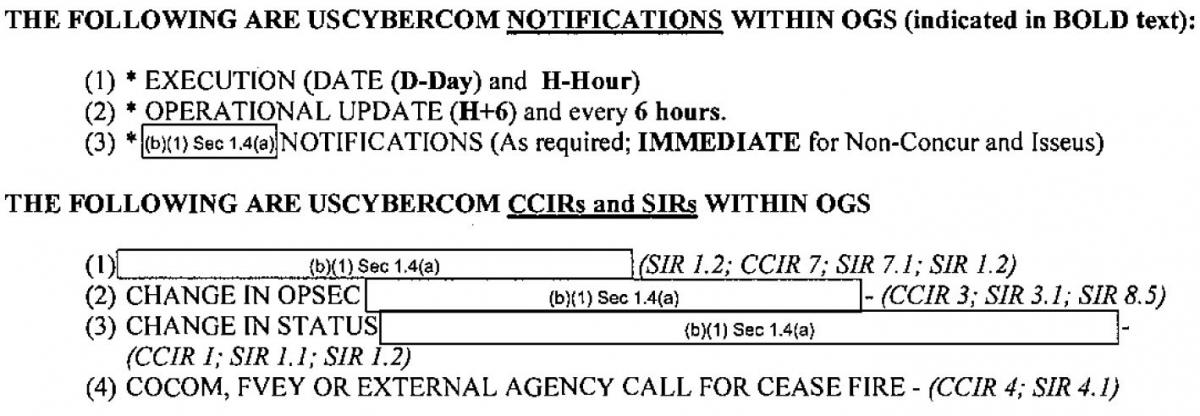

This checklist outlines the operation’s schedule for notifications and updates.

Standard updates to USCYBERCOM are required every six hours except in cases of internal disagreement, changes in mission parameters, or calls from other elements of the military to cease operations.

C2 – Command and Control

CCIR – Commander’s Critical Information Requirement

OPSEC – Operational Security

SIR – Specific Information Requirement

AUTHORIZATION OF OPERATION GLOWING SYMPHONY

2016-11-08

FRAGORD 06 to USSTRATCOM OPORD 8000-17: Authorization to Conduct Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY

This document, a Fragmentary Order amending the Operation Order containing all elements of USSTRATCOM’s planned activities for 2017, authorizes Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY. The Operation’s start, or “d-day”, is not given.

2016-11-09

USCYBERCOM OPORD 16-0188 OPERATION GLOWING SYMPHONY (OGS)

This document is largely a copy of the September 12 CONOP formalized as an actionable order. Some differences in details include, but are not limited to, the removal of a point on deconfliction (3.C.9.A in the CONOP) and greater detail in task assignments pertaining to manning, coordination, and deconfliction (3.D).

2016-11-10

JTF-ARES Briefing: Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY

This briefing condenses the information contained in OPORD 16-0188 into a presentable form.

2016-12-10

USCYBERCOM GENADMIN 16-0210 [redacted] OPERATION GLOWING SYMPHONY

This General Administrative Message (GENADMIN) notifies elements of the Department of Defense and the Intelligence Community of the existence of Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY, but provides very little information. The majority of the document’s body contains points of contact.

2017-07-01

USCYBERCOM GENADMIN 17-0093 EXTENSION OF OPERATION GLOWING SYMPHONY

This General Administrative Message indicates that Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY was ongoing as of July 2017.

Evaluating Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY

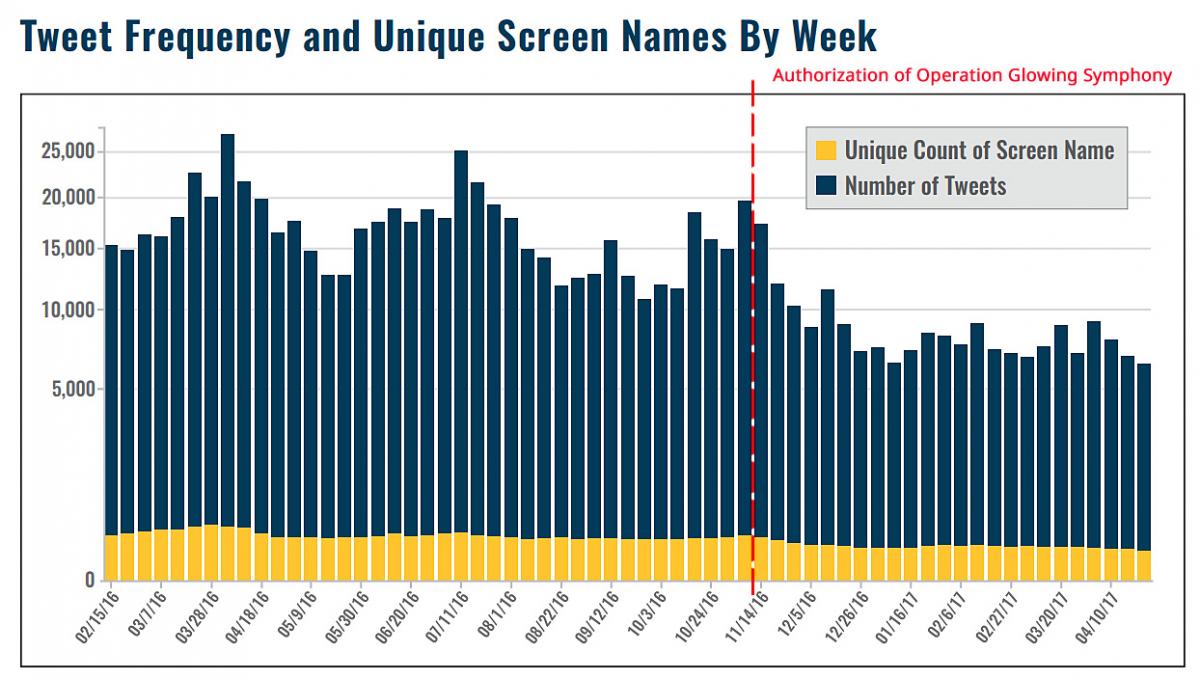

While there is very little data publicly available by which to judge Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY’s overall success or failure, a study of ISIL use of Twitter provides an intriguing correlation. Audrey Alexander, a researcher at the George Washington University Program on Extremism, tracks terrorist use of digital communications technologies. In 2017 Alexander published Digital Decay, an analysis of trends in English-language extremist activity on Twitter.

Her research showed a downward trend in activity from February 2016 through April 2017 that featured a boom-bust cycle up until November 2016 – when Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY was authorized. At this point activity dropped markedly and did not cycle back up.

Public understanding of the effectiveness of US cyber operations is hindered by secrecy, however the public nature of social media allows researchers like Alexander to trace trends in ISIL activities online and gives us an idea of the efficacy of cyber warfare.

More difficult to observe is the impact of cyber operations focusing in on Iraq and Syria, however isolated episodes have given a glimpse into the possibilities of cyber combined with kinetic counter-terror operations. Conflicting reports suggest ISIL hacker Junaid Hussein’s position was pinpointed when he either clicked on a malicious hyperlink or had his messages compromised before he was killed by a US drone as he left an internet café. More recently, US General Stephen Townsend described to military.com how cyber capabilities were used to interfere with communications from an ISIL headquarters in Iraq, forcing ISIL leadership to move to and reveal their backup command posts before kinetic strikes were ordered.

The planning process for Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY should look familiar to anyone acquainted with the military planning process, suggesting that cyber may not be revolutionizing the way the US military plans to fight wars as much as people may think. The execution and impact of counter-terror operations in cyberspace, however, speaks to the ways cyber is changing both how terrorist groups conduct global operations and how developed, sophisticated military forces are increasing lethality by integrating cyber with precision-strike tactics.