Washington, D.C., February 28, 2023 - In February 1998, 25 years ago this month, the United States suffered a series of cyber intrusions known as SOLAR SUNRISE that then-Deputy Secretary of Defense John Hamre called “the most organized and systematic [cyber] attack the Pentagon has seen to date.” Coming rapidly on the heels of ELIGIBLE RECEIVER 1997 (ER97)[1], a multi-agency, no-notice exercise that raised more questions than answers about how the government would handle an assault on U.S. cyber infrastructure, SOLAR SUNRISE was no drill. Like the hypothetical scenario presented by ER97 less than a year prior, the SOLAR SUNRISE attacks included the breaching of Department of Defense (DOD) networks by presumed international actors with possible geopolitical motivations and the involvement of civilian and private sector entities and infrastructure. Both episodes also raised a persistent question: Who's in charge here?

The documents highlighted here today to mark the 25th anniversary of SOLAR SUNRISE shed light on the intertwined mechanisms of diplomacy and investigation and suggest the need for a multi-agency response to emerging cyber threats. The records also stress the importance of civilian and private sector collaboration with cyber investigations and reveal the profound impact on U.S. cybersecurity preparedness of “two young hackers from California” who were operating “under the direction of a teenage hacker from Israel.” [Document 1, p.7]

The First Dawn

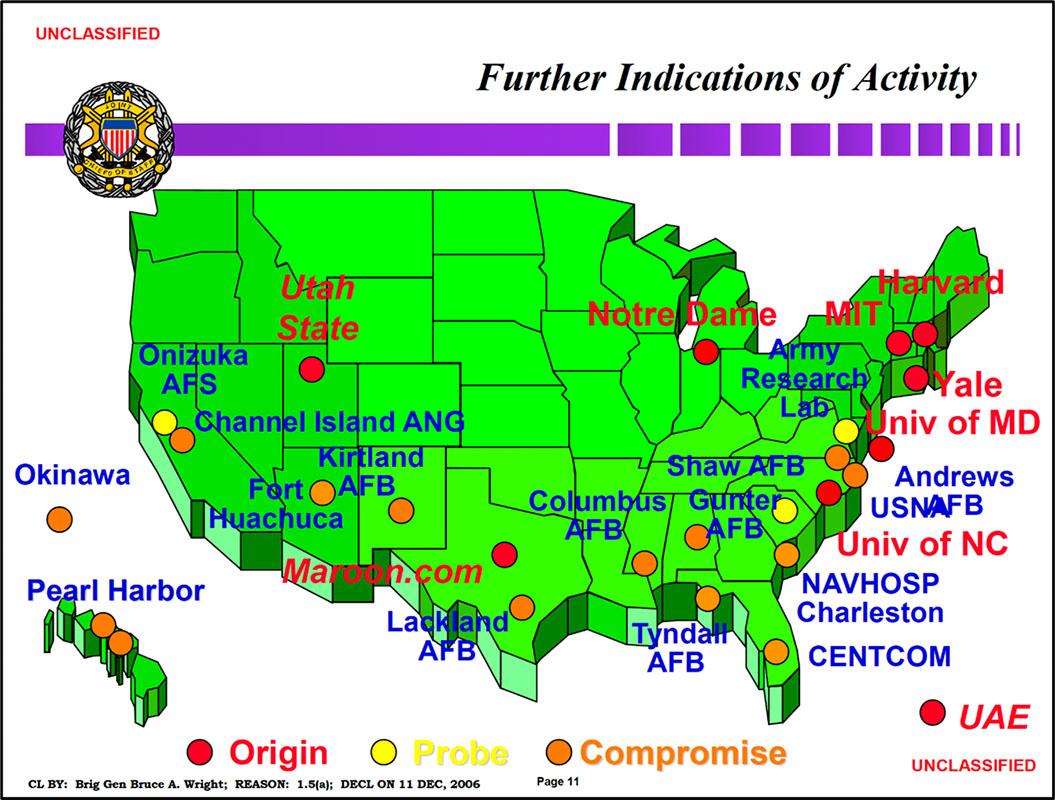

The series of government systems intrusions took place over a period of three weeks, from February 1-26, 1998, and focused on unclassified DOD systems. A February 25, 1998, FBI memo titled, “Solar Sunrise; CITA Matters,” describes the origin of the attacks, noting that, “The intruder appears to have targeted domain name servers and obtained root status via exploitation of the ‘statd’ vulnerability in the Solaris 2.4 operating system.” [Document 2, p.1] The memo further explains that, since February 1, “at least 11 DOD systems are known to have been compromised,” with intrusions or attempted intrusions detected at “Andrews Air Force Base (AFB), Columbus AFB, Kirkland AFB, Maxwell AFB (Gunter Annex), Kelly AFB, Lackland AFB, Shaw AFB, MacDill AFB, Naval Station Pearl Harbor, and an Okinawa Marine Corps Base.” [pp. 1-2] A slide from a 1999 presentation to the Joint Chiefs of Staff [Document 3] further illustrates the widespread distribution of the intrusions, which touched not only military systems but also those at universities like Harvard and Notre Dame and the private sector, including the internet service provider Maroon.com:

Document 4, p.11

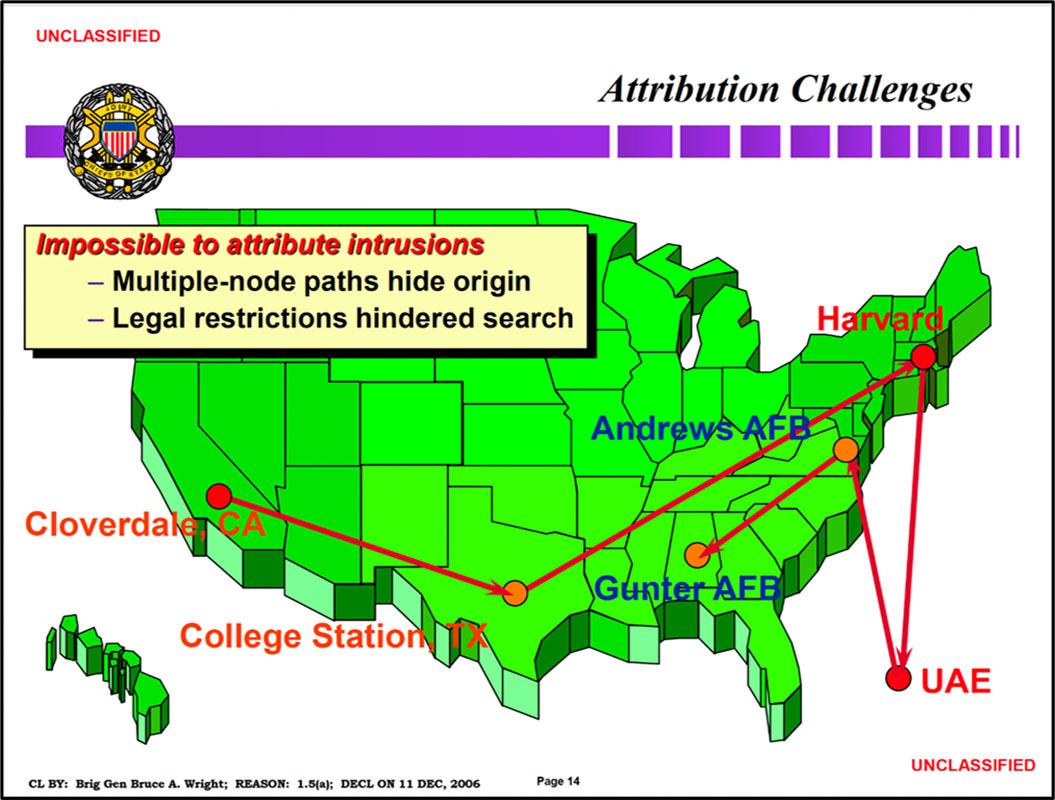

The presentation also highlights the challenges of attribution, as the multiple nodes the intruders traversed during the attack hid their origin and hamstrung parts of the investigation through legal restrictions:

Document 4, p.14

Although investigators from various agencies, including the FBI, the Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA) and the DOD, were unable to immediately identify the intruders or their country of origin, the use of a node in the United Arab Emirates, Emirnet, set off alarm bells that would echo to the highest levels of the Pentagon.

The Geopolitical Context

The first intrusions were detected just as the U.S. deployed roughly 2,000 Marines to Iraq to support and enforce weapons inspections that were part of the sanctions regime established after Iraq’s defeat in the First Gulf War (1991). After years of relative cooperation, in 1997 the Iraqi government refused to give inspectors access to certain areas, leading the UN Security Council to call for Iraq’s compliance through resolutions. Tensions escalated after the expulsion of American inspectors in October 1997 and Baghdad’s subsequent declaration in January 1998 that three specific sites would be off-limits. By February 6, 1998, a U.S. military intervention seemed imminent, with the deployment of some 2,000 Marines to the Persian Gulf, reinforced by a third U.S. aircraft carrier sent to the region.[2]

As the U.S. prepared to deploy the troops, the first intrusions into unclassified DOD systems were detected. In attempting to trace the path of the hackers, investigators discovered the use of Emirnet, an ISP in the United Arab Emirates and one of the only internet gateways into Iraq. This information, combined with the timing of the intrusions and the systematic targeting of DOD systems, prompted the question: Was the United States the victim of a cyber attack from Iraq?

An internal FBI memo from the National Security Division (NSD) and the Computer Investigations and Infrastructure Threat Assessment Center (CITAC) to all field offices affirmed these concerns, noting how “the scale and timing of these intrusions, which continue to occur as the United States prepares for major military operations, have raised major concerns for the Department of Defense.” [Document 4, p.1]

While the systems in question were unclassified, the critical information produced, stored, and transmitted on them was central to the DOD’s ability to continue operations in Iraq. In his June 1998 testimony to the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, then-CIA director George Tenet affirmed that, “while no classified systems were penetrated and no classified records were accessed, logistics, administration, and accounting systems were accessed. These systems are the central core of data necessary to manage our military forces and deploy them to the field.” [Document 1, p.7]

Similarly, a guidance document issued by U.S. Pacific Command (USPACOM) suggested that the intrusions had reduced the overall level of confidence in the integrity of the military and government systems built to prevent and detect them. While asserting that a “strong information systems security posture is vital to fully support day-to-day and contingency operations within the Pacific theater,” the directive warned that the system’s “current statd is suspect” and recommended the installation of “security patches.” [Document 5, p.3]. Furthermore, “users on the Solaris 2.4 operating system” were to review date/time stamps “to ensure the install dates are consistent with sys[tem] admin[istrator] activity.” The document further cautioned that “activity from .mil and .gov should also be reviewed. Do not assume trusted relationships exist.” Individuals were advised to “increase opsec [operational security] awareness of what is put on the NIPRNET.” [p.5]

A Collaborative Effort

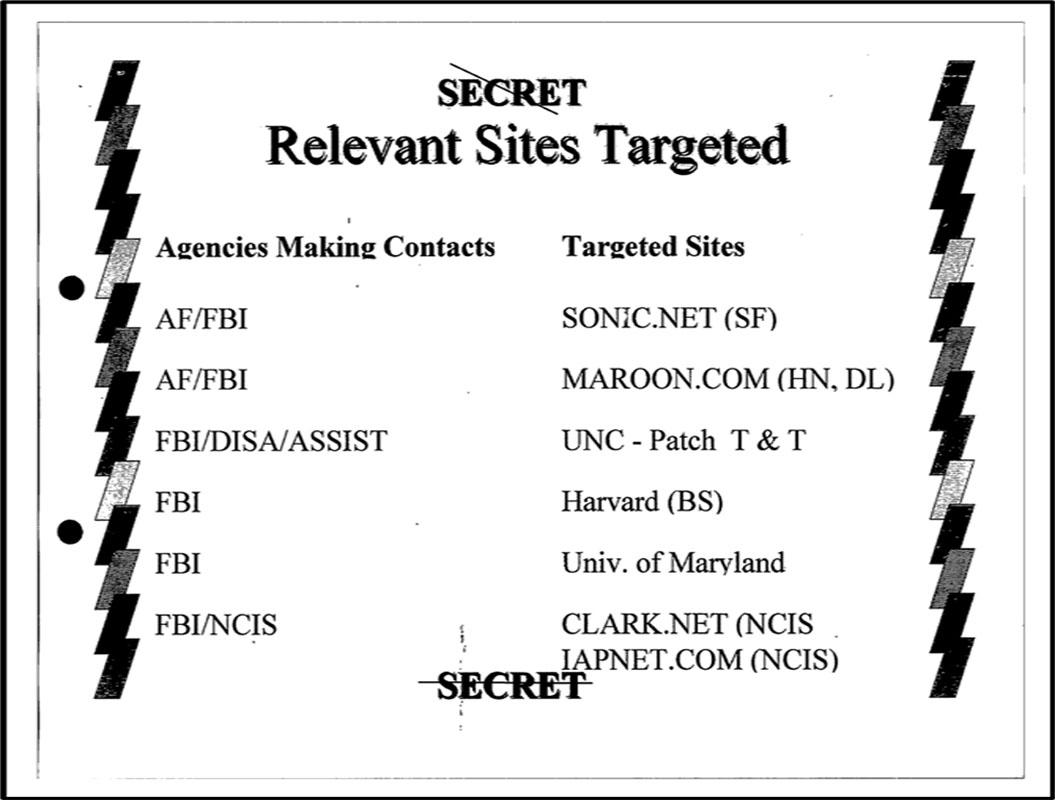

The documents reveal numerous questions and general uncertainty about the intrusions and the attackers’ likely next steps but also demonstrate the value of interagency collaboration and cooperation with civilians and the private sector. An undated FBI memo reminded its recipients, likely from different agencies and offices, about the burden of evidence required to get a court order (likely for a trap and trace), namely that the government must cite “specific and articulable facts showing that there are reasonable grounds to believe that the contents of a wire or electronic communication, or the records or other info sought, are relevant and material to an ongoing criminal investigation.” [Document 6, p.2] The document then reviewed the “relevant sites targeted” and aligned them with the agency or agencies involved with that site’s investigation:

Document 6, p.3

Other documents indicate that there was some level of cooperation between the agencies and various private entities, including universities and civilians. A February 24 FBI memo with the synopsis, “Results of interview with *redacted* of Computer Services Group, Harvard University” [Document 7], noted that, “System records from Harvard University were surrendered to SA [Special Agent] *redacted* WFO [Washington Field Office], on February 13, 1998, at approximately 3:00 pm…Boston [Field Office] is still obtaining consent from all system users for a full backup of Harvard’s computers.” [p.1-2]

Similarly, Document 8, a Statement of Complainant taken by the Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI) at Randolph AFB, reveals the willingness of some civilians with access to impacted or implicated systems to contribute to the investigation. In the statement, the complainant said that after learning that “an individual based on my machine…had illegally accessed military machines on the Internet” they had met with a field investigator from the Air Force. The statement noted that “the field agent would not take any information from me at the time and did not want any passwords or information” but rather “instructed me (if I was willing to cooperate and only then) to turn off the trimming of my log files in my crontab and not to change any configurations of the machine aside from that.” [p.3] The individual then requested from the field agent “general times that the hacking activity was noted as occurring,” which the agent supplied. Armed with this information, the individual issued the supplied commands to turn off trimming. Upon being contacted by another field investigator, the complainant affirmed that any assistive actions they had taken were “totally under my consent and [the field agent] made it perfectly clear to me that I didn't have to back up the hard drives or cooperate with them at all.” [p.4] On the cover sheet attached to the complainant's statement, the sender remarked, “Here's that statement - I'm still reading it. Looks like lots of good info. Our guys are on site trying to get through the [complainant-provided] system logs right now.” [p.1]

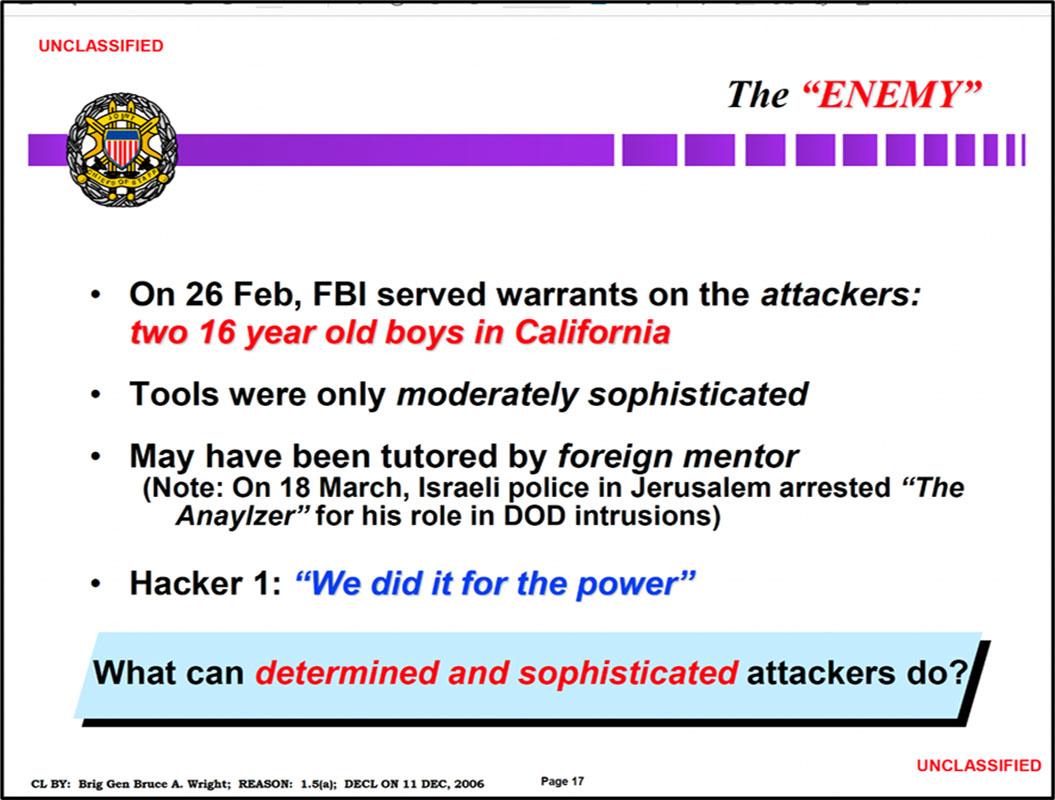

After three weeks of fevered investigation, investigators identified the perpetrators: two teenagers from Cloverdale, California, under the guidance of an older Israeli teenager, Ehud “The Analyzer” Tenebaum:

Document 4, p.17

Although the case came to an arguably positive conclusion, a troubling question remained: If kids can do this, what might determined and sophisticated hackers be able to do?

Meeting the Demands of a New Century

The lessons learned from both the ELIGIBLE RECEIVER 1997 exercise and the SOLAR SUNRISE attack spurred significant action from the U.S. government. In May 1998, the Clinton Administration released Presidential Policy Directive 63 [Document 9], which highlighted the “mutually reinforcing and dependent” relationship between the military and the economy:

Because of our military strength, future enemies, whether nations, groups or individuals, may seek to harm us in non-traditional ways including attacks within the United States. Because our economy is increasingly reliant upon interdependent and cyber-supported infrastructures, non-traditional attacks on our infrastructure and information systems may be capable of significantly harming both our military power and our economy. [p.2]

To better facilitate investigations and response to threats to critical infrastructure, PPD 63 formally authorized “the FBI to expand its current organization[3] to a full-scale National Infrastructure Protection Center (NIPC),” which shall serve “as a national critical infrastructure threat assessment, warning, vulnerability, and law enforcement investigation and response entity.” [p.12] The NIPC was tasked with providing “a national focal point for gathering information on threats to the infrastructures” and was to “provide the principal means of facilitating and coordinating the Federal Government's response to an incident, mitigating attacks, investigating threats and monitoring reconstitution efforts.” [p.13]

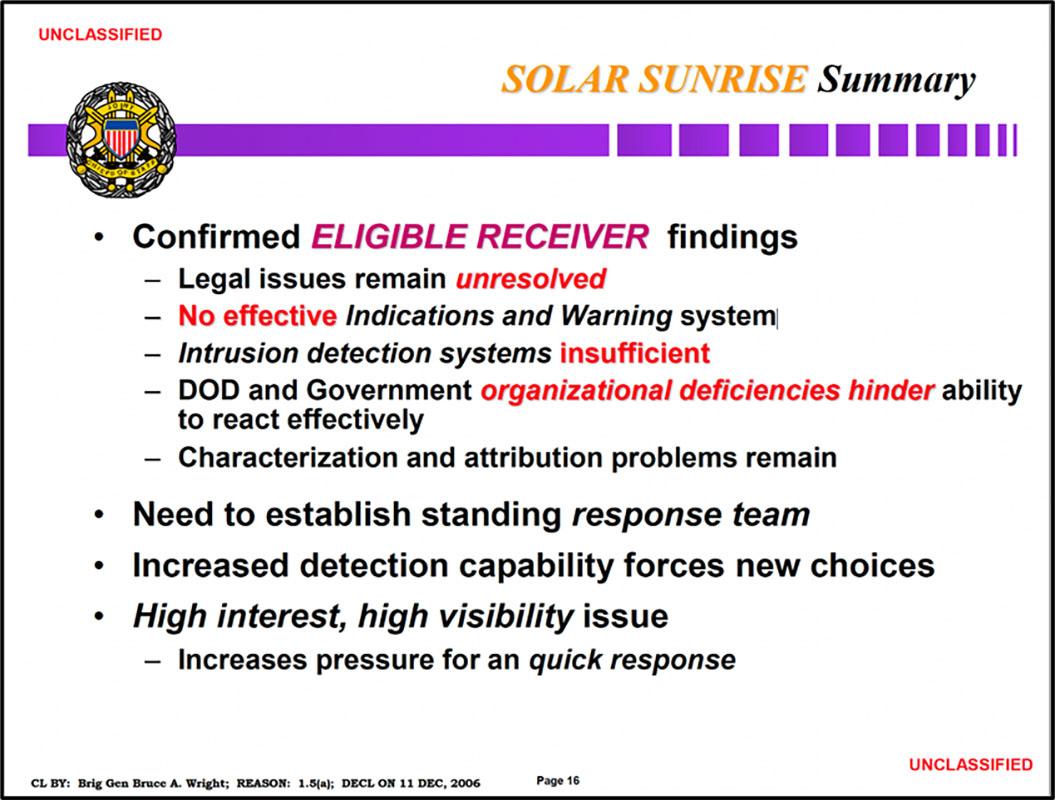

Perhaps SOLAR SUNRISE’s most valuable contribution was that it confirmed the findings of ELIGIBLE RECEIVER 1997:

Document 4, p.16

The NIPC, first helmed by Director Michael A. Vatis, was the first interagency fusion center created with the charge of closing or at least minimizing these gaps. In a conversation with the author, Vatis revealed that while PPD 63 provided a “presidential imprimatur” for the NIPC’s formal establishment, “the NIPC was stood up by DOJ/FBI in February [1998] – right as SOLAR SUNRISE was happening.” According to Vatis, although still in its infancy during the February attacks, the NIPC “proved the value of having a single entity be able to coordinate the investigation and interagency actions, which resulted in a fast conclusion to the investigation.”[4] In his October 1999 testimony to the Subcommittee on Technology, Terrorism, and Government Information of the Senate Judiciary Committee (“Examining the Protection Efforts Being Made Against Foreign-based Threats to United States Critical Computer Infrastructure”) [Document 10], Vatis outlined the NIPC’s integrative approach, fusing not only personnel from disparate but dependent agencies, but also mining expertise from the private sector:

The NIPC's mission clearly requires the involvement and expertise of many agencies other than the FBI. This is why the NIPC, though housed at the FBI, is an interagency center that brings together personnel from all the relevant agencies. In addition to our 79 FBI employees, the NIPC currently has 28 representatives from: DOD (including the military services and component agencies), the CIA, DOE, NASA, the State Department as well as federal law enforcement, including the U.S. Secret Service, the U.S. Postal Service and, until recently, the Oregon State Police. The NIPC is in the process of seeking additional representatives from State and local law enforcement.

But clearly we cannot rely on government personnel alone. Much of the technical expertise needed for our mission resides in the private sector. Accordingly, we rely on contractors to provide technical and other assistance. We are also in the process of arranging for private sector representatives to serve in the Center full time. In particular, the Attorney General and the Information Technology Association of America (ITAA) announced in April that the ITAA would detail personnel to the NIPC as part of a “Cybercitizens Partnership” between the government and the information technology (IT) industry. Information technology industry representatives serving in the NIPC would enhance our technical expertise and our understanding of the information and communications infrastructure. [pp.31-32]

Over two decades after his testimony, Vatis observes, “It’s striking to me that this lesson seems to have to be relearned continually—that there is no single agency that can handle all aspects of detection, warning, investigation, and response, but there does need to be an operational mechanism that is empowered to coordinate the activities of all the relevant agencies, international partners, state and local governments, and private sector entities.”[5] The U.S. has proposed and implemented a number of highly ambitious (but absolutely essential) programs to enhance information sharing and knowledge fusion in the past two decades, raising the question: Since the dawn of SOLAR SUNRISE, we’re 25 years older, but are we 25 years wiser?

The Documents

Document 1

This is the full transcript of the second in the series of 1998 hearings on cybersecurity before the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs. It focuses primarily on information security in the Department of Defense.

Document 2

Cyber Conflict Studies Association (CCSA) FOIA

This memo from the FBI’s Albuquerque Field Office to the National Security Division/Criminal Investigative Division and to the Las Cruces and Roswell Resident Agencies describes the progress of the SOLAR SUNRISE investigation and is intended to “set leads at Las Cruces [Resident Agency] and Roswell [Resident Agency].” It notes that the intruder(s) appear “to have targeted domain name servers and obtained root status via exploitation of the ‘statd’ vulnerability in the Solaris 2.4 operating system.”

Document 3

Jason Healey and Karl Grindal

This 1999 presentation to the Joint Chiefs of Staff describes events and findings of both ELIGIBLE RECEIVER 97 and SOLAR SUNRISE, noting that the SOLAR SUNRISE intrusions “Confirmed ELIGIBLE RECEIVER findings,” namely that “Legal issues remain unresolved,” that there is “No effective Indications and Warning system,” that the government’s “Intrusion detection systems” are “insufficient,” that “DOD and Government organizational deficiencies hinder ability to react effectively,” and that “Characterization and attribution problems remain.”

Document 4

CCSA FOIA

This memo from the FBI’s National Security Division provides guidance for press inquiries regarding SOLAR SUNRISE, noting that although “the investigation has been classified at the secret level…a fairly detailed report appeared in a technical publication,” leading the FBI to speculate that “there will be continued interest in this manner by the national press.”

Document 5

CCSA FOIA

This information security guidance document issued by U.S. Pacific Command (USPACOM) advises personnel advises the personnel of a potential vulnerability in the Solaris 2.4 operating system and requires them to “ensure the most current patches for your operating system are installed.” The memo also “request[s] network control centers take an active role in reviewing local intrusion detection system traffic to ensure quickest reaction possible to suspicious or malicious network activity.”

Document 6

CCSA FOIA

This undated FBI document lists the various sites targeted in the SOLAR SUNRISE investigation, as well as the range of agencies involved. The memo reminds investigators of the legal requirements to obtain a court order, namely, “articulable facts showing that there are reasonable grounds to believe that the contents of a wire or electronic communication... are relevant and material to an ongoing criminal investigation.”

Document 7

CCSA FOIA

This memo from the Boston Field Office to FBI headquarters reports that “system records from Harvard University were surrendered” to the FBI, but that the field office is “still obtaining consent from all system users for a full backup of Harvard’s computers.”

Document 8

CCSA FOIA

This statement from an unknown complainant, taken by the Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI), details one civilian’s enthusiastic cooperation with the SOLAR SUNRISE investigation. After the individual learns that their computer was involved in intrusions of military systems, they execute commands to preserve evidence and then surrender those logs and a system backup to investigators.

Document 9

Federation of American Scientists (www.fas.org)

The introduction to this directive notes that the U.S. military and economy are “increasingly reliant upon certain critical infrastructures and upon cyber-based information systems.” The remainder of the 18-page directive specifies the President’s intent “to assure the continuity and validity of critical infrastructures” in the face of physical or cyber threats. The directive also articulates a national goal, delineates a public-private partnership to reduce vulnerability, states guidelines, specifies structure and organization, discusses protection of Federal government critical infrastructures, orders a NSC subgroup to produce a schedule for the completion of a variety of tasks, and directs that an annual implementation report be produced. The directive also formally establishes the National Infrastructure Protection Center (NIPC) within the FBI, although the NIPC had been stood up in February 1998 during the SOLAR SUNRISE cyber intrusion investigation.

Document 10

U.S. Government Printing Office

The transcript from this hearing before the Subcommittee on Technology, Terrorism, and Government Information includes testimony from Michael A. Vatis, then director of the National Infrastructure Protection Center, and John S. Tritak, then director of the Office of Critical Infrastructure Assurance. Their testimonies detail lessons learned from exercise ELIGIBLE RECEIVER 1997 and the SOLAR SUNRISE cyber intrusion investigation, the variety of cyber threats on the horizon for critical infrastructure, and the efforts each office was making to prevent, detect, respond to and investigate cyber incidents.

Notes

[1] Analyses of ER-97 documents, Part I and Part II, can be found through the Cyber Vault Project.

[2] Tim Maurer, “SOLAR SUNRISE: Cyber Attack from Iraq?” A Fierce Domain: Conflict in Cyberspace, 1986-2012, pp. 121-123.

[3] The FBI’s “current organization” at the time was the Computer Investigations and Infrastructure Threat Assessment Center or CITAC, which was frequently referenced in the aforementioned documents.

[4] Michael A. Vatis, email message to the author, February 27, 2023.

[5] Ibid.