Washington D.C., February 22, 2019 – The movie VICE, nominated for eight Academy Awards including the best picture Oscar, shows on screen several documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. Those documents relate to then-Vice President Dick Cheney’s meetings with oil company lobbyists discussing potential drilling in Iraq. But at least a dozen other declassified records deserve screen time before Sunday’s Oscars show, according to the National Security Archive’s publication today of primary sources from Cheney’s checkered career.

The documents show how Cheney built a rap sheet for drunk driving and arranged draft deferments in the 1960s, pitched in on President Gerald R. Ford’s unsuccessful veto of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) in 1974, helped undermine investigations of CIA scandals in 1975, excused President Ronald Reagan’s Iran-contra misdeeds in 1987, mistakenly distrusted Gorbachev and slowed the end of the Cold War in 1989, promoted the global hegemon role for the U.S. in 1992, hid his work with oil companies in 2001 to set energy policy, endorsed torture and warrantless surveillance in the 2000s, played a leading role in trashing Iraq and the Middle East from the Iraq invasion in 2003 to the present, mysteriously went whole days at the White House without his Vice President’s office generating any saved e-mail, and presented a danger to civilians whether they were armed or not by shooting his hunting partner in 2006.

Common themes emerge from the documents, including Cheney’s long-standing commitment to defending and expanding presidential power, especially on national security matters, a predilection for the “dark side” in CIA operations from the scandals of the 1970s to the War on Terror, and his disastrously wrong foreign policy judgment. Cheney explained his intellectual history to reporters in 2005 by saying, “Watergate and a lot of the things around Watergate and Vietnam both during the ’70s served, I think, to erode the authority I think the president needs to be effective,” and went on to cite the Iran-Contra congressional committee minority report published below.[1]

The documents posted today provide fascinating context for some of Cheney’s most famous moments. After 9/11, on September 16, 2001, Cheney told NBC’s Tim Russert, “We also have to work, though, sort of the dark side, if you will. We've got to spend time in the shadows in the intelligence world. A lot of what needs to be done here will have to be done quietly, without any discussion, using sources and methods that are available to our intelligence agencies, if we're going to be successful.” Just before the invasion of Iraq, on March 16, 2003, Cheney told Russert that when the United States goes in, “we will, in fact, be greeted as liberators.” The vice president was adamant: “to suggest that we need several hundred thousand troops there after military operations cease, after the conflict ends, I don’t think is accurate. I think that’s an overstatement.” Cheney’s message proved to be far from correct. According to a December 2014 Congressional Research Report entitled, “The Cost of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Other Global War on Terror Operations Since 9/11,” the United States spent an estimated $815 billion on the Iraq War, including military operations, base support, weapons maintenance, training Iraq security forces, reconstruction, foreign aid, embassy costs, and veterans’ health care, while more than 4,410 Americans were killed in action and 31,957 wounded in action during the fighting in Iraq.[2]

Read the documents

Document 01

A lengthy Washington Post profile of then-Secretary of Defense Cheney after the first Gulf War included his explanation that he did not serve in Vietnam because, “I had other priorities in the ’60s than military service.”[3] The military draft classification history of Cheney, published by Politifact, details those other priorities, showing that beginning in March 1963, Cheney received five deferments. The first four were for “activity in study” (Cheney attended the University of Wyoming after flunking out of Yale in June 1962), and the fifth, issued in January 1966, was for “registrant with child … or deferred by reason of extreme hardship to dependents.” As Timothy Noah of Slate pointed out, “Dedicated students of obstetrics will observe that Elizabeth Cheney’s birth date [July 28, 1966] falls precisely nine months and two days after the Selective Service publicly revoked its policy of not drafting childless husbands …. Who says government policy can’t affect human behavior?”[4]

Document 02B

Dick Cheney’s drunk driving arrests have been a matter of public record since at least 2001, when he described to The New Yorker magazine “a couple of scrapes with the law” in his youth and the Smoking Gun web site published the actual Wyoming police and court records. Subsequently, in a 2015 interview with Playboy Magazine, Cheney recalled that, “I was headed down a bad road after I had been kicked out of Yale. I had been arrested twice for DUI when I was a 22-year-old.”[5] Although refusing to discuss the details of the DUIs, he said, “I didn’t hit anything. There were no accidents involved. I was drinking and driving, and there was no question I was guilty.” According to Bob Woodward’s account in The Commanders, Cheney disclosed the arrests to the Senate Armed Services Committee in 1989 after his nomination for secretary of defense in a closed confirmation hearing. According to Woodward, Cheney told the committee that he wanted to disclose the arrests, but committee members stated there was no need to release the information and subsequently voted 20-0 to confirm him.[6] Ironically, the SecDef nomination was only available for Cheney because the George H.W. Bush administration’s first choice, Texas Senator John Tower, lost his Senate confirmation vote 53-47 in large part due to allegations of excessive drinking. The docket from Cheyenne’s municipal court shows that Cheney was arrested the first time for “operating motor vehicle while intoxicated and disturbances” in November 1962. As punishment, Cheney’s license was suspended for thirty days and he forfeited his $150 bail bond. The second time Cheney was arrested for drunk driving was in July 1963. Although there appears to be no remaining docket of the arrest, a Rock Springs Police Department police arrest card, which includes the code for DWI, “11-44,” shows that Cheney was arrested and fined $100 for his second driving-while-intoxicated conviction.

Document 03

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Published in National Security Archive Briefing Book No. 142, “Veto Battle 30 Years Ago Set Freedom of Information Norms: Scalia, Rumsfeld, Cheney Opposed Open Government Bill”

In the wake of Watergate and Richard Nixon’s resignation in August 1974, President Gerald R. Ford attempted to set a new open government tone in the White House, for example inviting reporters in to see him toast his own English muffins for breakfast. Ford’s new chief of staff, former Illinois congressman Donald Rumsfeld (a leading character in VICE as Cheney’s mentor), had been one of the original sponsors of the 1966 Freedom of Information Act, and Ford – who himself had voted for FOIA then – initially wanted to approve the new strengthening amendments to the law passed by Congress in 1974. But heightened concerns about leaks (driven by Rumsfeld and his deputy, Cheney) and arguments that the new amendments intruded on presidential powers (promoted by Justice Department lawyer Antonin Scalia) persuaded Ford to veto the bill. This example of handwritten notes of the first White House senior staff meeting presided over by Rumsfeld and Cheney show that a sizable portion of the meeting focused on Rumsfeld’s concern about leaks – exactly at the moment in September 1974 when Ford was thinking about the FOIA bill. Other contemporary documents quote Scalia’s admonitions to the director of the CIA and other high-ranking officials that they “should move quickly to make their view [supporting the veto] known directly to the president.” Cheney, Rumsfeld, and Scalia were successful in convincing Ford to veto the legislation. But they were not successful in blocking the law. The House overrode Ford’s veto 371-31 and the Senate 65-27.

Document 04

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, Richard Cheney Files, Intelligence Series, Box 7, Folder, "Rockefeller Commission Report: Final (1)." Published in John Prados and Arturo Jimenez-Bacardi, National Security Archive Briefing Book #543

Files at the Ford Presidential Library show Cheney’s hands-on role in protecting the CIA from outside investigations in the wake of multiple revelations of prior intelligence abuses uncovered by Congress and the media, and downplaying “dark side” activities as merely “improper” rather than illegal. Having succeeded Rumsfeld as White House chief of staff, Cheney used his power to alter the supposedly independent 1975 Rockefeller Commission investigation report on the CIA’s domestic activities. Cheney’s handwritten edits to key portions of the report eliminated a provision that would have allowed CIA employees to report improper activity to the agency’s Inspector General, and removed the entire treatment of "Alleged Plans to Assassinate Certain Foreign Leaders,” replacing it with a brief text asserting that the commission had not had the time to cover the subject. Where the original, presidentially-appointed Rockefeller Commission text concluded that several CIA activities, including domestic spying, were unlawful, Cheney’s edits watered down those judgments to describe the actions as merely “improper.” The Rockefeller Commission had flatly described as wrong the government’s actions of keeping files on, and creating lists of, political dissenters. Cheney's revisions, however, gave the impression that “many” of these records had somehow been inadvertently created by the application of certain inappropriate “standards.”

Document 05

After his tour in the Nixon White House, Dick Cheney won election to Congress from Wyoming, in a campaign memorably reported in VICE featuring his wife, Lynne Cheney, doing the honors, denouncing bra-burning on the campaign trail while Cheney recovered from the first of his heart attacks. (Amy Adams has a Best Supporting Actress Oscar nomination for her troubles.) Cheney quickly rose in the Republican leadership, who in 1987 assigned him a coveted spot on the joint House and Senate investigation of the Iran-Contra affair that had cost President Reagan the greatest one-month decline in approval ratings in Gallup Poll history. While serving on the committee, Cheney praised serial prevaricator Oliver North (eventually convicted of three felonies, now serving as president of the National Rifle Association) as “the most effective and impressive witness certainly this committee has heard.”[7] At the conclusion of the hearings, Cheney, five other House Republicans, and two Senate Republicans issued a minority report (largely authored by committee staffer Michael J. Malbin, a political science professor) disputing the majority conclusions. Warren Rudman, the Republican vice chairman of the Senate side of the investigation, called Cheney’s Minority Report “pathetic” and paraphrased an Adlai Stevenson quip, stating, “this particular report is one in which the editors separated the wheat from the chaff and, unfortunately, it printed the chaff.”[8] The Minority Report described the bipartisan Majority Report as “hysterical” and insisted that although “President Reagan and his staff made mistakes in the Iran-Contra affair,” they were merely “mistakes in judgment, and nothing more. There was no constitutional crisis, no systematic disrespect for the 'rule of law,' no grand conspiracy, and no administration-wide dishonesty or cover-up.” Cheney’s view of unbridled executive power is clearly evident in the Minority Report. Even as the report acknowledged that Reagan violated the 1984 Bolan amendments by raising third-party funds for the Contras, it reached the conclusion that the President was allowed to break this law because, “we are firmly convinced that the Constitution protects such diplomacy by the president or by any of his designated agents —whether on the NSC staff, State Department or anywhere else.”

Document 06

George H.W. Bush Presidential Library; National Security Council Files; Kanter, Arnold Files; Subject File; Summit (Malta) – November 1989 [5]; OA/ID Number: CF00770-022

President George H.W. Bush appointed Dick Cheney as secretary of defense after Bush’s first choice, John Tower, lost his Senate confirmation vote due to allegations of alcoholism and other improprieties. The Bush team in many ways represented the coming of the “hawks” after the Reagan “doves” who had negotiated elimination of intermediate-range nuclear missiles in 1987. Bush resented Gorbachev’s international popularity (and Reagan’s) and defined his strategic mission as “Getting Ahead of Gorbachev” (in the words of one key memo in spring 1989), rather than understanding the Soviet leader’s unilateral offers as an arms race in reverse.[9] One of Cheney’s greatest legacies in public office is his leading role in the failure to capitalize on Gorbachev’s disarmament proposals, which were very much in the interests of U.S. national security. Russia today possesses thousands of tactical nuclear weapons that Gorbachev was willing to reduce, but Cheney stood in the way. Even among the Bush hawks, Cheney stood out as “the most skeptical,” according to national security adviser Brent Scowcroft, “holding the view that the changes [in Moscow] were primarily cosmetic and we should essentially do nothing.”[10]

As secretary of defense, Cheney served as a negative check against all of Bush’s attempts to come up with arms control initiatives that would match what Gorbachev was offering, until it was almost too late, in September 1991, after the hardline coup against Gorbachev had failed, when Bush unilaterally removed tactical nuclear weapons from U.S. ships (along with several other de-escalations) and Gorbachev reciprocated. The Soviet leader had offered exactly this move two years earlier, at the Malta summit, but Cheney’s recalcitrance and misjudgment of Gorbachev prevented any progress. This document is one of hundreds of examples in the record of Cheney’s obstructionism: a November 1989 memorandum from National Security Council staffers Arnold Kanter and Robert Blackwill (part of a series in the Kanter files of ideas for arms control initiatives) that comments “Reading between the lines of today’s meeting, it appears as though Cheney and [Colin] Powell may resist all efforts to advance any concrete ideas or initiatives [for arms reductions] at Malta. They are innately suspicious of any such approach … Cheney is said to believe that our effort to assess possible initiatives is a ‘bad idea.’”

Document 07

Department of Defense Mandatory Declassification Review request. Published in William Burr, “’Prevent the Reemergence of a New Rival’: The Making of the Cheney Regional Defense Strategy 1991-1992,” National Security Archive Briefing Book 245

From February to May 1992, Secretary of Defense Cheney, who portrayed himself as a “[s]elf-described and proud of it hawk… who never met a weapons system he didn’t vote for,”[11] oversaw the completion of the first post-Cold War Defense Planning Guidance. According to the detailed account by James Mann in a chapter titled “Death of an Empire, Birth of a Vision” in his book Rise of The Vulcans,[12] the lead author was Zalmay Khalilzad (now President Trump’s envoy to Afghanistan, but then an assistant to defense undersecretary for policy Paul Wolfowitz).

On March 8, 1992, a leaked draft of the document made front-page headlines in The New York Times, “U.S. Strategy Plan Calls for Ensuring No Rivals Develop.” Wolfowitz and his drafters, led by I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, recast the document so that it would pass public scrutiny while meeting Cheney's requirements for a strategy of military supremacy. In a March 31, 1992, cover memo of a draft, Libby wrote to Cheney that the latest draft had softened the phrases about acting “unilaterally” and “alone” to such phrasings as “with only limited additional help.” Foreshadowing 2003 Iraq War’s “Coalition of the Willing,” Libby justified the changes to Cheney by stating, “we believe these formulations are more defensible” because the U.S. would always “have at least political support from some limited number of countries.” Below his signature approving a May draft of the document, Wolfowitz wrote, “Scooter and his folks have done a remarkable job. We have never had a Defense Guidance this ambitious before.”

Although the Department of Defense’s release of these documents has been fragmentary, the National Security Archive has catalogued and analyzed every available draft of the guidance, including its official unclassified version. Expert Freedom of Information Act requesters will note that many sections have been blacked out, citing the pre-decisional Exemption Five. The 2016 FOIA Improvement Act Amendments have now forbidden such redactions for documents older than twenty-five years.

Document 08

Sierra Club and Judicial Watch FOIA lawsuit

Despite oil industry denials to Congress and Cheney’s claims of executive privilege–which led to a lawsuit that ultimately reached the Supreme Court–White House visitor logs revealed that Cheney’s Energy Policy Task Force met with approximately 300 groups and individuals from February to April 2001. The vast majority of these meetings were with representatives of the fossil fuels industry. Among the recommendations produced by the Task Force in May 2001 was the recommendation to “support initiatives by Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Algeria, Qatar, the UAE, and other suppliers to open up areas of their energy sectors to foreign investment.” Although not mentioned in the official report, Energy Policy Task Force documents won by a Sierra Club and Judicial Watch FOIA lawsuit–and featured in VICE–included a map of Iraqi oilfields, pipelines, refineries, and terminals and charts of Iraqi oil and gas projects.

Document 09

The public has yet to see the full record of President George W. Bush’s and Vice President Dick Cheney’s meeting with the 9/11 Commission. The two agreed to meet with the Commission only if there was no recording or formal transcription of the session, and if the commissioners met the two together, not individually. The Commission Report cites the testimony of every other key actor as an “interview,” but uniquely calls the Bush and Cheney discussion the “President Bush and Vice President Cheney meeting.” Commission Chairmen Thomas Kean and Lee Hamilton have written that the Bush-Cheney refusal to be interviewed separately and insistence that no formal recording or transcription be made was “tied to their view of presidential privilege.”[13] To this day, neither the Commission nor the administration’s notes of the meeting are available to the public. The 9/11 Commission documents are held by the U.S. National Archives, which states, “Because the Commission was part of the legislative branch its records are not subject to the Freedom of Information Act.”

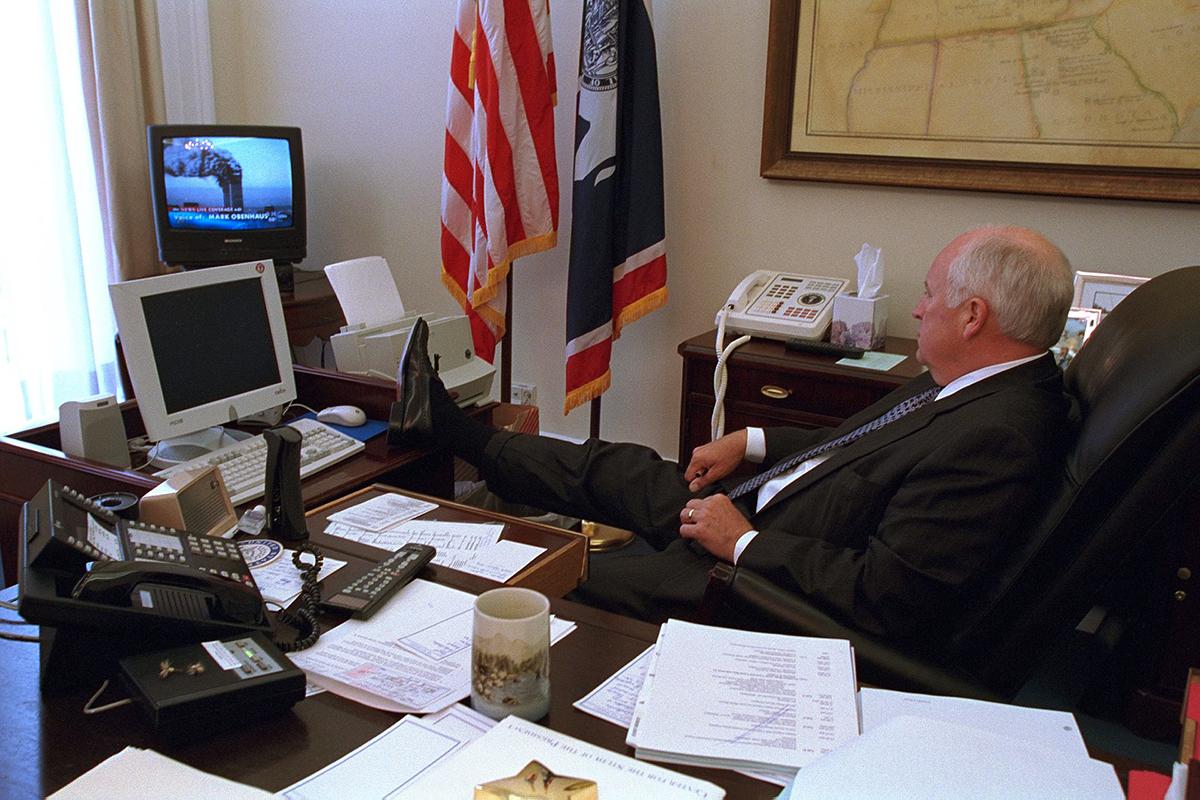

According to the 9/11 Commission, after watching the second plane strike the World Trade Center, Cheney entered an underground tunnel leading to the White House shelter at 9:37 A.M. There, Cheney took charge. One of the issues that would come up about his role at the time had to do with the authorization to shoot down United Flight 93 and other potentially hijacked aircraft. The Commission’s report found “conflicting evidence” as to who issued the orders. Cheney has stated that the President authorized rules of engagement of the combat air patrol over Washington during a phone call with the vice president at just after 10:00 A.M. The president told the Commission at its sole meeting with him–Dick Cheney listening at his side–that he recalled such a conversation and that “it reminded him of when he had been an interceptor pilot.” Whatever the substance of the conversation, Scooter Libby recalls that in a call with the Defense Department minutes later, Cheney authorized military aircraft to engage Flight 93 “in about the time it takes a batter to decide to swing.” After Cheney’s authorization, White House Deputy Chief of Staff Joshua Bolten approached Cheney and suggested that the vice president “get in touch with the President and confirm the engage order.”

Document 10

CIA Freedom of Information Act release, 2014/09/11 C06238939

The CIA’s embrace of torture after 9/11 as standard treatment for suspected terrorists is well documented, not least in the massive Senate Intelligence Committee report declassified in 2014 that details all the ways the CIA lied to themselves and their superiors about torture’s effectiveness.[14] Less well documented is then-Vice President Dick Cheney’s leading role in justifying and supporting the torture program. This CIA memo from 2003 was one of the exhibits published by a group of former CIA officers under the rubric “CIA Saved Lives” but, as Georgetown Law professor David Cole commented, the CIA officers intended these records to be “exculpatory” in the sense that they show CIA did not act on its own, since the White House and Justice Department approved, but in fact they are arguably “inculpatory” since they show so many other senior officials involved.[15] This White House meeting is one of a sequence, as President George W. Bush or his spokespeople or other government officials asserted that the U.S. was treating detainees “humanely,” and CIA Director George Tenet, who knew better, sought White House assurances his people were not being left out on a limb. What is striking about this July 29, 2003, meeting is the role Cheney plays. After Tenet and his counsel Scott Muller open the meeting and Attorney General John Ashcroft asserts his total support for the program, it is Cheney who asks how the media could have gotten the impression that “stress and duress” techniques are prohibited. When the number of waterboarding sessions administered to 9/11 planner Khalid Sheik Mohammed is mentioned (119), it is Cheney who remarks that KSM was a “tough customer.” When Tenet asks to make sure CIA is carrying out administration policy, “not merely acting lawfully,” it is Cheney who reassures him.

Document 11

Then-Vice President Cheney’s chief of staff, Scooter Libby (a lead author of the 1992 Defense Policy Guidance) was caught up in a special counsel investigation in 2005 over the issue of who leaked the covert identity of CIA operative Valerie Plame. The details of the story are far too convoluted to spell out here, involving Plame’s husband, Joe Wilson, and faked intelligence justifying the invasion of Iraq, but the second-to-last paragraph of this letter to Libby’s lawyers from the special counsel contained the bombshell: “In an abundance of caution, we advise you that we have learned that not all email of the Office of Vice President and the Executive Office of President for certain time periods in 2003 was preserved through the normal archiving process of the White House computer system.” By April 2007, the public interest group Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW) had found a whistleblower alleging as many as five million emails had gone missing. By September 2007, both the National Security Archive and CREW had sued the White House to compel recovery of emails; and in 2009 the Obama administration not only settled the lawsuits but recovered as many as 22 million emails that had been missing from earlier archiving efforts.[16] Entire days in 2003 (exactly the period of the invasion of Iraq) had featured zero e-mails from the Office of the Vice President in the inventory of the White House e-mail system. When Presidential Records Act restrictions on George W. Bush documents elapse in 2021, the missing emails will no doubt rank at the top of the list for Freedom of Information Act requests.[17]

Document 12B

On February 11, 2006, Dick Cheney accidentally shot his hunting partner, Harry Whittington, in the face, on a ranch in Texas. Within days, given the media interest, the local sheriff released an incident report, and the Smoking Gun web site published the document. Although the movie VICE depicts Cheney shooting Whittington from the back of an automobile, Whittington stated in a recent interview that the incident happened when the hunting party was on foot, following dogs which flushed the quail. After a bird flew into the air, Cheney, according to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Hunting Accident and Incident Report, “swung on a bird and fired striking Whittington in the face, neck and chest at approximately 30 yards.” Cheney shot Whittington with a 28-gauge Perazzi Brescia shotgun loaded with birdshot. The incident occurred on Saturday, February 11, but the Kenedy County Sheriff’s Department Incident Report states that neither Cheney nor the other witnesses were interviewed until the next day, February 12. The owner of the ranch, prominent Republican activist and former Ambassador to Great Britain Anne Armstrong, told the Corpus Christi Caller-Times that Cheney had been involved in a hunting accident at 11:00 AM on February 12, 2006. The White House did not announce the incident until the afternoon of February 12. The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department released a Hunting Accident and Incident Report on February 13. The Kenedy County Sheriff’s Department released its Incident Report on February 16. The statements and affidavits of the hunting party have not been released to the public.

NOTES

[1] Richard W. Stevenson and Adam Liptak, “Cheney Defends Eavesdropping Without Warrants,” The New York Times, December 21, 2005.

[2] Amy Belasco, “The Cost of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Other Global War on Terror Operations Since 9/11,” Congressional Research Service, December 9, 2014. Posted at Federation of American Scientists.

[3] Phil McCombs, “The Unsettling Calm of Dick Cheney,” The Washington Post, April 3, 1991.

[4] Timothy Noah, “Elizabeth Cheney, Deferment Baby,” Slate, March 18, 2004.

[5] See James Rosen, “The April 2015 Playboy Interview with Dick Cheney,” March 1, 2015.

[6] Bob Woodward, The Commanders (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991), p. 70.

[7] See Sean Wilentz, “Mr. Cheney’s Minority Report,” The New York Times, July 9, 2007. North’s convictions were later vacated on a technicality.

[8] See George Lardner, “GOP Minority Denounces Panel Findings as ‘Hysterical,’” Washington Post, November 19, 1987.

[9] For extensive detail on the Bush administration’s characteristic insecurity vis-a-vis Gorbachev in 1989, see Thomas Blanton, “U.S. Policy and the Revolutions of 1989,” in Svetlana Savranskaya, Thomas Blanton, and Vladislav Zubok, ‘Masterpieces of History’: The Peaceful End of the Cold War in Europe 1989 (Budapest/New York: CEU Press, 2010.

[10] See George Bush and Brent Scowcroft, A World Transformed (New York: Knopf, 1998), p. 44.

[11] Address to the American Enterprise Institute Forum, February 21, 1991.

[12] See James Mann, Rise of the Vulcans: The History of Bush’s War Cabinet (New York: Viking Penguin, 2004) pp. 198-215.

[13] See Thomas H. Kean and Lee H. Hamilton with Benjamin Rhodes, Without Precedent: The Inside Story of the 9/11 Commission, (New York: Knopf, 2006), p. 207.

[14] See National Security Archive Briefing Book No. 497, “Torture Report Finally Released.”

[15] See David Cole, “’New Torture Files’: Declassified Memos Detail Roles of Bush White House and DOJ Officials Who Conspired to Approve Torture,” Just Security, March 2, 2015.

[16] See “National Security Archive and White House Reach Agreement for Restoration of Missing Bush White House E-mails,” December 14, 2009; for the back story, see “White House Admits No Back-Up Tapes for E-mail Before October 2003.”

[17] See Nina Burleigh, “The George W. Bush White House ‘Lost’ 22 Million Emails,” Newsweek, September 12, 2016.