Washington, D.C., December 17, 2018 – During the dark days of the Cold War, spying on the enemy often took place in broad daylight. Some of the best opportunities for Western intelligence to get a picture – literally – of Soviet capabilities were presented by the USSR itself at public military parades, where the normally secretive Soviets proudly showed off to the world their arsenal of advanced hardware.

High-resolution photography from overflights, satellites, and even handheld cameras enabled the West to take accurate measurements and gather important details of various components. Additionally, identification of the participating military units contributed to order of battle intelligence. The presence of officials on the reviewing stand, their interactions, and speeches shed light on the nation’s political and military leadership, data coveted by Kremlinologists in the West.

Todays’ posting by the National Security Archive, based at The George Washington University, features documents from the Central Intelligence Agency, Defense Intelligence Agency, and U.S. Army. It includes records concerning coverage of a variety of military parades and intelligence reports based on the imagery obtained at those events. Many of the latter include copies of photos taken at the time.

James E. David, curator of national security space programs at the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum, compiled and introduced this Electronic Briefing Book.

Communist Parades as an Intelligence Target

By James E. David

Technical intelligence is information on the design, dimensions, configuration, and performance of weapons systems. It is critical in establishing their exact capabilities and in determining the forces and weapons to build to counter them. Various sources contribute to technical intelligence. These include high-resolution overhead and ground photography, the interception and analysis of telemetry from aircraft, missiles, rockets, and spacecraft; the overt or covert acquisition and analysis of weapons systems; the acoustic, seismic, and radiological sensors of the Atomic Energy Detection System; the overt or covert acquisition of technical documents and scientific publications; and human sources.[1]

A common definition of photographic resolution is the distance two objects need to be apart to be distinguished as separate from each other.[2] The U.S. intelligence agencies did not specifically define high-resolution, but instead determined the resolutions necessary to provide different levels of technical intelligence. In the 1960s, they concluded that a resolution of around three feet was adequate to establish the existence and identity of targets such as major weapons systems. A resolution of about one foot provided critical additional information on a wide range of military targets, including missiles, naval vessels, aircraft, and certain ground force equipment.[3]

Various photoreconnaissance aircraft were capable of collecting high-resolution imagery of the USSR, but there were few overflights due to their extremely provocative nature, formidable air defenses, and the massive area to be covered. The U-2, whose B camera achieved a maximum resolution of two feet, photographed 15% of the nation during 24 successful overflights beginning in 1956.[4] However, they ended permanently when the Soviets shot down Gary Powers’ plane in 1960.

High-resolution photoreconnaissance satellites became operational several years later. GAMBIT-1, launched 38 times from 1963-1967, eventually achieved a best resolution of two feet. The follow-on GAMBIT-3 flew 54 missions from 1966-1984. Its maximum resolution remains classified, except for the fact that it was initially greater than two feet and apparently improved to better than one foot. HEXAGON, which flew 19 missions from 1971-1984, had a best resolution of two feet.[5] The resolution obtained by KENNEN, the first digital return system initially launched in 1976, remains classified.

Although the high-resolution imagery from the U-2 and satellites satisfied many technical intelligence requirements, it rarely captured certain critical targets. These included intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and shorter-range surface-to-surface ballistic missiles. Even before their deployment in silos beginning in the mid-1960s, these vehicles were stored in buildings at their launch complexes. Submarines carried their ballistic missiles (SLBMs) in tubes and their cruise missiles in protective housings. Silos housed anti-ballistic missiles (ABMs). The U-2 and, later, satellites, frequently photographed aircraft on runways and aprons. However, they could not capture the underside, engine inlets, and certain other important features. Similarly, these overhead platforms were limited in some respects in photographing armor, artillery, mobile radars, and other ground force equipment.

U.S. and allied intelligence personnel and service attachés used handheld cameras to photograph a wide range of targets during their trips in the USSR. Intelligence agencies also acquired imagery taken by tourists and business visitors. However, with the severe travel restrictions imposed on Westerners and the massive security around military installations these efforts did not capture many weapons.

In contrast, parade photography frequently did. The resolutions achieved in this imagery are unknown, but the best must have been about several inches. Annual parades included the May Day parade held on 1 May as part of the celebration of International Workers’ Day and the October Revolution Parade held on 7 November as part of the commemoration of the Bolshevik takeover in 1917. Although the largest parades took place in Moscow, other Soviet cities held them as well. Moscow also occasionally hosted an air show in July that emphasized military aircraft.

It is worth pointing out that although the Soviets were notoriously skittish about opening themselves up to surveillance of any kind and, as noted, sharply restricted travel and even photography by Westerners, those concerns apparently did not outweigh a collective sense of pride and a determination to show off their military prowess to the world. At most they occasionally used canisters when displaying missiles for the first time, such as the GALOSH in the November 1965 parade. However, in later years they would display the missiles themselves in the open.

DOCUMENTS

Document 01

CREST (CIA Records Search Tool) database

This report, submitted by an unknown CIA official, described this event’s civilian and military participants and the ships and installations in the harbor area of this important Far East Soviet city. Undoubtedly, similar reports were submitted by State Department officials and service attachés soon after each parade. However, most remain classified.

Document 02

CREST database

Based on observations and photography of aircraft at the May Day parade and its rehearsals, this CIA memo estimated the technical specifications of the new jet heavy bomber and new jet medium bomber. The United States and NATO soon designated the former BISON and the latter BADGER. Both were seen in flight and photographed for the first time at these events. Development of bombers was a top priority intelligence objective because they greatly increased the nuclear threat to the United States and its allies. Based on several factors, the memo stated that the heavy bomber was probably a prototype, while the medium bomber was already in series production.

Document 03

CREST database

This evidently was an outline of a briefing given to the National Security Council. The presence of up to ten BISONs flying together in rehearsals for the upcoming May Day parade and estimates of Soviet production capacity led the Air Force to increase dramatically the numbers that it believed would be deployed in coming years. It had previously estimated that the aircraft would not be in operational units until the end of 1956 and that only 50 would be in service by mid-1957. The Air Force now estimated that the Soviets would produce 55 by the end of 1955 and 247 by the end of 1957. These numbers initiated the "bomber gap" controversy within the U.S. intelligence community and the public at large that continued until U-2 overflights in 1956 and 1957 conclusively proved the number of long-range bombers was much smaller.[6]

Document 04

CREST

Along with the new bombers, the May Day parade in Moscow also displayed several new or modified artillery pieces, including a 200mm gun-howitzer.

Document 05

CREST

This entry discussed the key speech at the November parade in the Soviet capital. The military hardware in the parade was of "modest proportions" and did not include any new aircraft or ground force equipment.

Document 06

CREST

This parade displayed little military hardware, but Defense Minister Georgy Zhukov's speech was notable in several respects, including its lack of belligerency.

Document 07

CREST

This CIA memo listed the aircraft that participated and the presence of refueling probes on at least four BISONs. BISONs, BEARs, and BADGERs were bombers, the FLASHLIGHT A a reconnaissance aircraft, and the FARMER and FRESCO variants of the MiG fighter.

Document 08

CREST

Based on imagery, this joint Army-CIA-Navy report analyzed in detail the five missiles displayed for the first time. They included the SA-1B surface-to-air missile, a short-range ballistic missile with an estimated range of 15 nautical miles (nm), the SS-1 ballistic missile with an estimated range of 75-100 nm, a short-range ballistic missile with an estimated range of 35 nm, and the SS-3 ballistic missile with an estimated range of 350 nm. The United States and NATO eventually designated the SA-1 GUILD, the SS-1 SCUD, and the SS-3 SHYSTER.

Document 09

CREST

This CIA memo described the observations made at long distances by the U.S. air attaché at the first rehearsal for the annual Moscow parade.

Document 10

CREST

This entry summarized the May Day celebrations for 1958 throughout the Sino-Soviet Bloc. In Moscow, the military portion of the parade was brief and did not contain any new equipment.

Document 11

CREST

This was a CIA memo from the Guided Missiles Branch in the Directorate of Intelligence to the Requirements Branch in the same directorate. Although U.S. and British military attachés would be covering the upcoming May Day parade in Moscow, the Guided Missiles Branch requested coverage of the parades in other major Soviet cities to observe and photograph any missiles. With the redactions, it is cannot be determined what personnel would do this.

Document 12

CREST

This entry described the November parade in Moscow, in which the emphasis was on peaceful coexistence with the West and disarmament. Only ground force equipment was displayed, and the sole new weapon was a multiple rocket launcher.

Document 13

CREST

With the exception of two new artillery rockets, all the missiles displayed this year had been seen for the first time at the 1957 November parade. Analysts believed the SS-3 SHYSTER was deployed in the western USSR and possibly in East Germany.

Document 14

Record Group (RG) 319, Entry NM-3 47-Q3, Box 13; National Archives, College Park, Maryland (NARA)

This memo from the head of the Scientific and Technical Branch to the head of the Collection Division under the Army's Assistant Chief of Staff (Intelligence) stated that the close-up photography acquired during the May Day parade was an improvement over previous parade photography and was very useful. However, analysts needed additional high-resolution imagery of several weapons, including the SWATTER anti-tank missile and the BRDM armored vehicle that carried them. Additionally, if possible they needed samples from the nose cones of missiles and observations or photography up the aft end of missiles.

Document 15

CREST

The CIA's National Photographic Interpretation Center, which also included personnel from the military services, National Security Agency, and the Defense Intelligence Agency, prepared this report on the new surface-to-air missile displayed. The missile did not match any of the known surface-to-air missiles during this period and might have been an experimental vehicle.

Document 16

RG 319, Entry NM-3 47-R3, Box 20; NARA

In this memo to the Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, the head of the Collection Division expressed strong opposition to a proposal to bring undeveloped film of the Moscow parades to the Air Force’s Foreign Technology Division for processing and analysis. Immediately following these events, the U.S. attachés normally processed not only their film but also that taken by the British, Canadian, and French attachés. The U.S. attachés prepared preliminary reports, and couriers brought the materials to the United States within a few days for further exploitation. Interestingly, the memo describes night photography of a new track-mounted missile that attachés presumably acquired with some type of infrared film.

Document 17

CREST

From the photographs, this was the surface-to-air missile that the United States and NATO soon designated SA-4/GANEF.

Document 18

CREST

The SKEAN, also designated SS-5, was a nuclear-tipped intermediate-range ballistic missile spotted in Moscow in 1964.

Document 19

CREST

The GOA surface-to-air missile, observed in the Soviet capital in 1964, also had the U.S. and NATO designation of SA-3.

Document 20

CREST

Soviet anti-ballistic missiles (ABMs) were a top priority of U.S. intelligence. U.S. and allied personnel apparently saw several GALOSH ABMs for the first time at the November 1964 parade. Although housed in canisters, the aft end of the booster was visible and the photography enabled analysts to make some measurements.

Document 21

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

Reflecting White House interest in intelligence on Soviet missiles, this entry briefly described the three new missiles at the recent 9 May parade. (The parade, celebrating the 20th anniversary of the Nazi surrender, replaced the May Day parade this year.) The Soviets reported that one missile was a small solid-propellant ICBM capable of launch from silos and a second a launch vehicle. Analysts concluded that the third truck-mounted tactical missile was likely a new version of the SCUD.

Document 22

CREST

This Defense Intelligence Agency report described and measured the three new missiles seen in the recent parade in Moscow, as well as the T-62 tank and an anti-tank missile seen for the first time. It also contained a list of all the military equipment displayed.

Document 23

CREST

By the date of the publication of this report, the United States and NATO had designated the new small ICBM SS-13/SAVAGE. Analysts concluded the new larger vehicle, initially reported by the Soviets to be a launch vehicle, was in fact an ICBM and it carried the designation SS-X-10/ SCRAG. They determined the new truck-mounted tactical missile, designated SS-14/SCAMP, was not a new version of the SCUD but a completely new intermediate-range missile.

Document 24

CREST

The Soviets reported that this missile, designated SS-15/SCROOGE and observed for the first time in the November 1965 Moscow parade, was a mobile, solid propellant ICBM.

Document 25

CREST

Displayed for the first time in November 1965, the short-range and unguided FROG 7 varied in several respects from earlier versions. It was also on a new transporter-erector-launcher.

Document 26

CREST

A new transporter-erector-launcher carried a SCUD B, a medium-range ballistic missile at the November Moscow parade.

Document 27

CREST

The fire-control radar observed in 1965 and 1966 provided data to a fire-control system to direct the guns so that they hit the target aircraft.

Document 28

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

This entry discussed a remark made by a Soviet officer to a U.S. attaché in Moscow that the upcoming summer air show would be “very interesting.” U.S. officials were not surprised since 1967 was the 50th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution. They thought the Soviets might display new fighters, transports, and a vertical take-off-and-landing aircraft.

Document 29

Interagency Security Classification Appeals Panel

This CIA report described the aircraft at the Moscow air show on 8 and 9 July. New ones included several conventional fighters, a vertical take-off-and-landing fighter, a short take-off-and-landing fighter, and a transport. Analysts concluded that only a twinjet all-weather interceptor was currently in production. The Soviets also displayed BLINDER supersonic-dash medium bombers with a new air-to-surface missile.

Document 30

CREST

This memo, addressed to the heads of various CIA intelligence production offices, emphasized that the upcoming November parades in the Sino-Soviet Bloc would probably be of major intelligence importance since they would be celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution. It requested the submittal of requirements for coverage of the Moscow parade and noted that there may be requirements issued for coverage of other activities related to the celebrations. The actual requirements promulgated remain classified.

Document 31

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

The weapons displayed at the parade the day before included a probable SS-9 ICBM, an unknown missile (which the Soviet commentator said was submarine-launched but which analysts concluded was too large for a submarine), an unknown medium- or intermediate-range missile, a probable SS-12 short-range missile and a truck-mounted antitank missile.

Document 32

CREST

Before the creation of the House and Senate intelligence committees in the late 1970s, the CIA regularly briefed the CIA Subcommittees of the House and Senate Armed Services Committees and the House and Senate Appropriations Committees. The CIA Subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee requested a presentation on the recent parade at its 9 November 1967 meeting.

Document 33

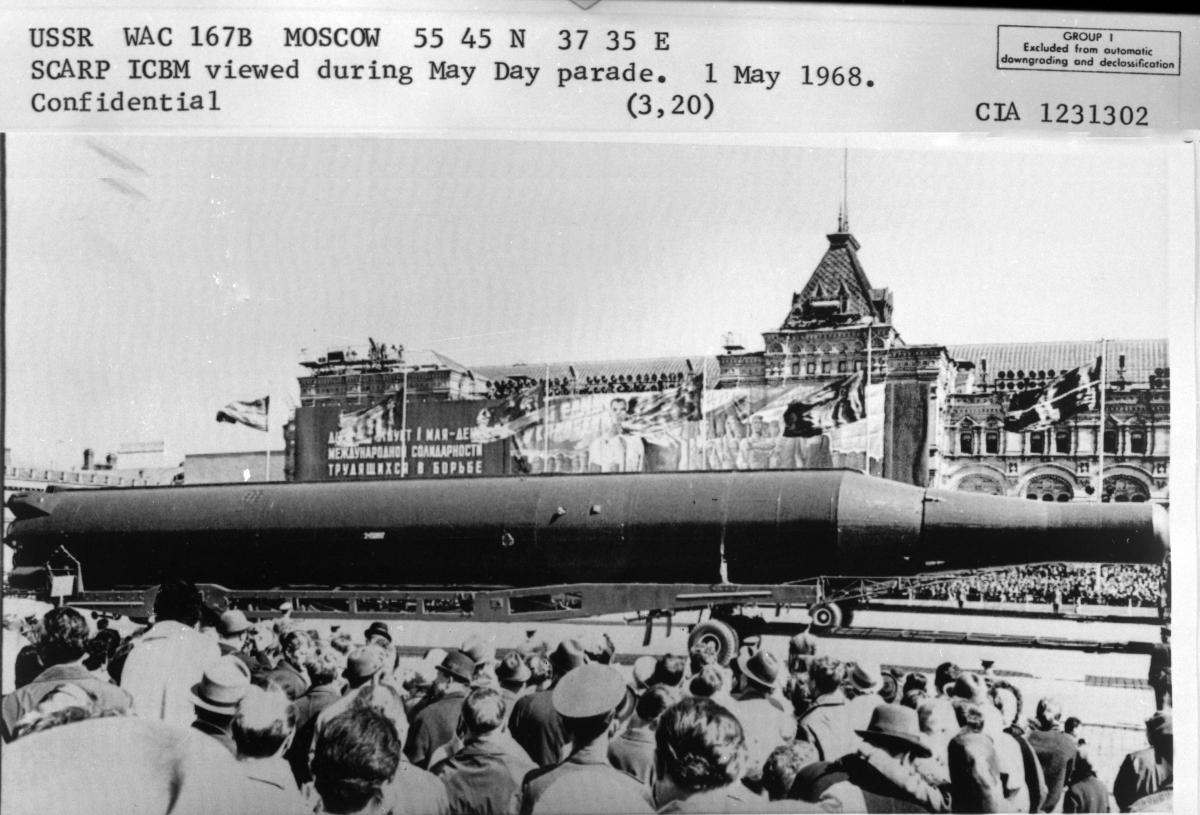

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

This short entry described May Day 1968 in Moscow as "uninspiring" and noted that the parade did not display any new weapons.

Document 34

CREST

The November 1967 Moscow parade displayed a new version of the GUIDELINE surface-to-air missile, more commonly known as the SA-2.

Notes

[1] Robert M. Clark, “Scientific and Technical Intelligence Analysis”, Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Spring 1975), CREST (CIA Records Search Tool) database. Dino Brugioni, Eyes in the Sky; Eisenhower, the CIA, and Cold War Aerial Intelligence (Naval Institute Press: Annapolis, 2010), pp. 50-64.

[2] Robert A. McDonald, Ph.D. and Patrick Widlake, “Looking Closer and Looking Broader: Gambit and Hexagon – The Peak of Film-Return Space Reconnaissance After Corona,” National Reconnaissance – Journal of the Discipline and Practice, January 2012, p. 2.

[3] Requirements for Satellite Photography for about the Next Five Years, COMOR-D-13/23, 4 November 1964, CREST (CIA Records Search Tool) database.

[4] Memorandum for Brigadier General Andrew J. Goodpaster, 19 August 1960, CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room.

[5] “Looking Closer and Looking Broader,” pp. 2-9.

[6] See, e.g., William E. Burrows, Deep Black – Space Espionage and National Security (New York: Random House, 1986), pp. 68, 81; L. Parker Temple III, Shades of Gray – National Security and the Evolution of Space Reconnaissance (Reston: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2005), p. 70; Donald P. Steury, Ed., Intentions and Capabilities: Estimates on Soviet Strategic Forces, 1950-1983 (Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency, 1996), pp. 5-6.