Washington, D.C., July 12, 2011 - What were the 11 words the government didn’t want you to see?

The aspect of the June 13 release of the full Pentagon Papers that has received the most attention is perhaps the U.S. Government’s attempt to keep under wraps 11 words on one page that had in fact been in the public domain since the government edition of the Papers was published by the House Armed Services Committee (HASC) in 1972. At the eleventh hour the censors, after intervention by National Archives and Presidential Library staff, abandoned that idea and left the words in the text, thus avoiding drawing attention to them. Still, speculation has been rife about what the “11 Words” were.

Classification authorities were quite right—from the standpoint of protecting secrecy—to leave the text as it stands. This makes it impossible to know what bit of the Pentagon Papers was at issue, and with the 11 Words embedded in more than 7,000 pages of text, identifying them precisely poses a huge challenge. Because the 11 Words were originally declassified long ago, there is nothing to highlight them, and the mass of the text makes it difficult just to review the material. Only speculation is feasible.

In keeping with the numerical motif, the National Security Archive here offers 11 possibilities for the identity of the 11 Words. There were two criteria for selection: that the information seemed somehow significant, and that it not figure among any of the newly declassified passages.

1. CONSIDERING A COUP AGAINST NGO DINH DIEM IN AUGUST 1963 (IV. B. 5, p. iv): The analyst explains two broad views in USG, that (1) there was no realistic alternative to Diem or (2) that war against NLF could not possibly be won with Diem in power. Text continues, “The first view was primarily supported by the military and the CIA both in Washington and in Saigon.” [In this possibility, the knowledge being protected would be agreement between CIA and the military on defending Diem’s rule. Presumably the deletion would preserve the general public impression that more sophisticated CIA views about Vietnam always differed from military ones. The problem with this approach is both that the early identity of views is apparent in a multitude of other evidence, and also that there is different evidence showing the CIA helping the Kennedy administration identify potential South Vietnamese leaders other than Diem.]

2. SIMPLE ID of a CIA DOCUMENT (IV. C. 1, p. 23): Relates to the Temporary Duty (TDY) Group sent to South Vietnam to study conditions in the post-Diem period. Apparently two (of three) cables sent were attributed to it mistakenly but were actually from CIA’s chief of station in Saigon. “The ‘Initial Report of CAS Group Findings in SVN,’ dated 10 February 1964 began by acknowledging that the group activities had been temporarily disrupted by the Khanh coup.” [This excision would represent an attempt by the CIA censors to protect the identity of a particular document, supposedly shielding it from FOIA requests. The problem with that strategy is that the several cables referred to, which contain the substance of the study group report, have been declassified for many years. “CAS” in this text stands for “Controlled American Source,” a euphemism used in Vietnam for the CIA.]

3. COVERT ATTACKS ON NORTH VIETNAM (IV. C. 1, p. 83): Discussing what the U.S. might do under various conditions as of mid-June 1964, the analyst writes: “The proposed ‘Elements of a Policy That Does Not Include a Congressional Resolution’ consisted largely of an elaboration of covert measures that were already either approved or nearing approval. This included RECCE-STRIKE and T-28 operations all over Laos and small-scale RECCE STRIKE Operations in North Vietnam after appropriate provocation.” [This is an interesting candidate for the 11 Words for two reasons. First, it reminds the public that Washington was set on air strikes against North Vietnam earlier than usually remembered—a fact that has become obscure over time. Second, and most important from the standpoint of war powers, it shows that the administration believed it had the authority to initiate bombing operations without any congressional action at all. These 11 Words, if this was the actual candidate language, would be of primary interest to the White House. In the sentence quoted, “Recce” is a shortened form for “reconnaissance,” and T-28 is a type of propeller-driven fighter-bomber.]

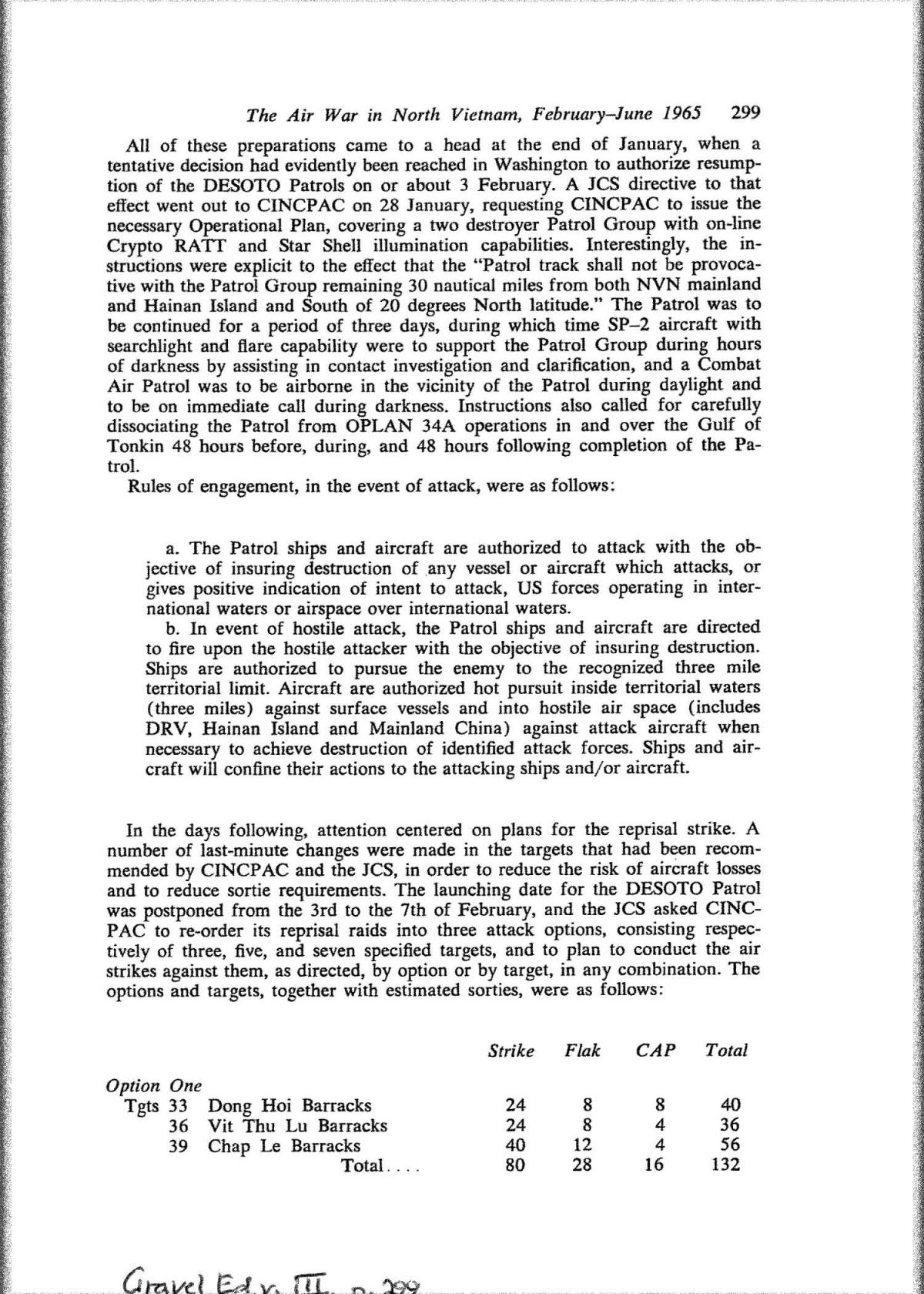

4. NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY (NSA) EQUIPMENT REVEALED (IV.C.3, p. 17): Analysts describe the instructions issued for an electronic monitoring mission called a DE SOTO Patrol to be sent into the Tonkin Gulf in early February 1965. They note that The Joint Chiefs of Staff instructed U.S. Pacific commanders to structure their operations plan “covering a two destroyer Patrol Group with on-line Crypto RATT and Star Shell illumination capabilities.” [This possibility would be consonant with NSA predilections for deleting anything that concerns its activities, even though the agency itself has declassified the fact of the presence of NSA detachments on DE SOTO Patrol destroyers. The likely rationale would be that “on-line Crypto RATT” identifies a particular communications device, a secure-line radio teleprinter. The device would have been in the suite of the NSA van placed on one of the destroyers. The problem with this redaction is that when the National Security Agency in 2008 declassified a mass of materials pertinent to the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, one of those items identified all equipment in the NSA vans, including the actual designation of this device.]

5. ACTION AGAINST CAMBODIA (IV. C. 6 (b), p. 38): Describing proposals by U.S. Pacific theater commander Admiral U.S. Grant Sharp in early 1967, the Pentagon Papers analyst quotes text from Sharp’s cable identifying one major problem as the North Vietnamese sanctuaries in Cambodia and discussing potential countermeasures. In the course of his dispatch Admiral Sharp notes “it is understood that a Joint State, Defense and CIA committee is considering this problem.” [The eventual U.S. solution—which dragged Cambodia into the war without actually solving the sanctuary problem, was to invade Cambodia in the spring of 1970. This deletion would have the effect of disguising how early in the war the U.S. was considering such measures.]

6. BOMBING NORTH VIETNAM (IV. C. 7 (a), p. 53): The Pentagon Papers analysts paused in their narrative at intervals to assess the effects of bombing North Vietnam. In their discussion of the aerial campaign’s status at the end of 1965, the analysts noted “Of 91 known locks and dams in NVN, only 8 targeted as significant to inland waterways, flood control, or irrigation.” [There has been a lively debate in the United States as to whether U.S. forces sought to encourage flooding in North Vietnam. This is usually timed as having occurred in 1972 and formulated as “bombing the dikes.” The U.S. Government position has been—despite some evidence to the contrary—that no measures of this kind were ever taken and that damage to dikes, if any, must have been inadvertent. The issue is complicated in that U.S. air commanders would have regarded bombing of dams and locks associated with North Vietnamese waterborne supply movements as legitimate military targets. On the other side is the fact that destruction of dikes and levees is listed as a general option in the 1967 bombing volume as well. However, this text indicates intent related to a specific number of targets, and that North Vietnamese water control mechanisms were targeted from very early in the air campaign known as Rolling Thunder.]

7. CIA ON BOMBING NORTH VIETNAM, MARCH 1966 REPORT (IV. C. 7 (a), p. 83): “The March CIA report, with its obvious bid to turn ROLLING THUNDER into a punitive bombing campaign and its nearly obvious promise of real payoff . . .” [The CIA is not supposed to involve itself in policy. This possibility for the 11 words would disguise a fairly explicit statement by a Pentagon Papers analyst that the agency was doing precisely that. The problem with this redaction is that in quite a few passages the Pentagon Papers treat the CIA as another Washington agency whose views needed to be taken into account.]

8. DEFECTOR PROVIDES INTELLIGENCE, MARCH 1968 (IV. C. 7 (b), p. 154): In his discussion of the evolution of Rolling Thunder during the period after the Tet Offensive of early 1968, the Pentagon Papers analyst indicates that the CIA input of a report on Soviet and Chinese aid to North Vietnam of March 2 “was based on the report of a high-level defector and concluded with a disturbing estimate of how the Soviets would react to the closing of Haiphong harbor.” [This is one of those classic deletion options supposed to protect CIA “sources and methods.” However, it is difficult to see what would be protected by deleting this information in 2011, considering that the material had been in the open for the entire period since 1971, and that the identities of all North Vietnamese, Chinese, and Soviet defectors were inevitably known to the security services of those countries. In addition, nothing in the Pentagon Papers divulges the actual identity of the intelligence source.]

9. FIRST APPROVAL OF U.S. AIR STRIKES (IV. C. 9 (a), p. 63): During the Saigon political crisis of January 1965, in which General Nguyen Khanh made the latest in the series of coups, countercoups, and self-coups that bedeviled South Vietnam during the 1963-1965 period, the Pentagon Papers analyst notes that, “In the midst of the crisis General Westmoreland obtained his first authority to use U.S. forces for combat within South Vietnam. Arguing that the VC might go for a spectacular victory during the disorders, he asked for and obtained authority to use U.S. jet aircraft in a strike role.” [This major change in U.S. rules of engagement and combat authorities in Vietnam took place virtually without notice. Previously it had widely (though incorrectly) been understood that U.S. forces were not engaged in direct combat in South Vietnam. Moreover, with respect to aircraft, the general impression has been that the use of American jets against North Vietnam in so-called “tit for tat” strikes represented the moment when the rules changed. In addition, Westmoreland’s permission to engage was subject merely to the agreement of the U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam, without reference to Washington. In the context of today’s debates over war powers, especially in Libya, this public domain language, long open, might have seemed more sensitive. This is another deletion that, if made, would have favored the White House.]

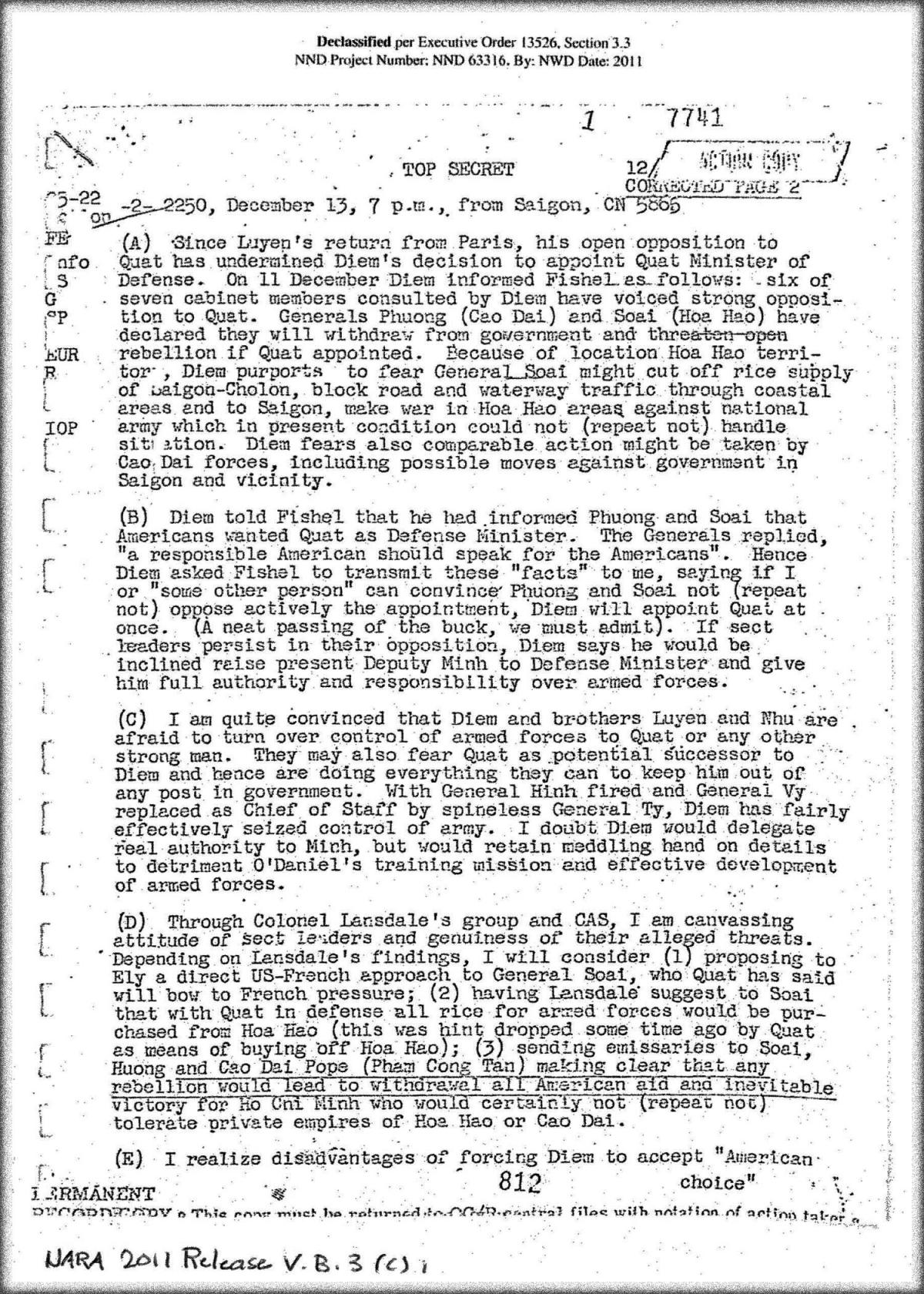

10. CIA ROLE IN DIEM’S 1955 SAIGON PUTSCH (V. B. 3, p. 812): In the appended volumes of collected documents which it includes, the Pentagon Papers contain a December 13, 1954 cable from U.S. chargé d’affaires Randal Kidder to the State Department in which he reports that “Through Colonel Lansdale’s group and the CAS, I am canvassing attitude of sect leaders and genuineness of their alleged threats.” The CIA’s role in Diem’s 1955 political maneuvers, in which the agency covertly funded Diem and drove a wedge between South Vietnam’s political-religious sects that enabled the Saigon leader to defeat them, is among the most important and least explored aspects of the United States role in Vietnam. At the height of a Saigon political crisis in the spring of 1955, the investment sunk into the Diem option led the CIA to obstruct the policy of the U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam. In the light of troubles with Diem later on, the CIA role at this early stage is no doubt even more embarrassing. [The CIA continues today to resist the declassification of agency histories of these activities. They were probably surprised to find in this long-declassified document a confirmation that that activity was in progress. This episode is controversial because some evidence indicates that CIA director Allen W. Dulles colluded with his brother, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, to subvert the policy of President Dwight Eisenhower’s designated personal representative, General J. Lawton Collins.]

11. NSA INTERCEPTION OF SOVIET LEADERS’ TELEPHONE CONVERSATIONS (VI.C.3 (1), p. 61-62): This possibility for the intended deletion is as intriguing as it is misconceived. In February 1967, in the course of a Johnson administration peace feeler known as SUNFLOWER, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson made certain representations in President Johnson’s behalf to Soviet leader Alexei Kosygin. Kosygin promptly reported the approach to his colleague Leonid Brezhnev by encrypted telephone: “at 9:30 a.m. today according to a telephone intercept Kosygin called Brezhnev and said [there was] a great possibility of achieving the aim.” [This redaction would presumably be intended to shield an NSA intercept program from the Russians. The idea that any such aim could be accomplished is unrealistic for a number of reasons. First, syndicated columnist Jack Anderson wrote about this NSA program as early as 1971. Second, this statement occurs in the middle of a passage that similarly reveals the NSA knew—undoubtedly also from interception—which ciphers Kosygin was using in written communications (the “President’s Cipher”), and could identify by their length in specific numbers of code groups the resultant cables into and from the Soviet embassy in Hanoi. In other words, there was much more to protect in this passage than the telephone intercepts. Third, the diplomatic volumes were not part of the 1972 declassification. When a version of the diplomatic volumes was declassified, in 1978, this passage was permitted onto the public record in its entirety. In fact, the whole set of revelations was published in 1983, when historian George C. Herring edited a version of these volumes, The Secret Diplomacy of the Vietnam War: The Negotiating Volumes of the Pentagon Papers (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1983, p. 468-9). Fourth, the same language was again released in 2003 when the U.S. government fully declassified the diplomatic volumes.

As noted at the outset it is impossible for anyone other than the censors to know what the 11 Words in fact are. The above suggestions should be considered as no more than possibilities. Of these selections, those regarding the Diem coup, the covert attacks on North Vietnam (in two possibilities), the considerations of Cambodia, and the first approval of U.S. airstrikes, are relevant to debates about legal authorities to make war. Aside from their historical importance, there seems little reason for the imposition of secrecy. The case that concerns CIA assessments of bombing North Vietnam, and that of the Agency’s role in Diem’s 1955 powerplay are about the CIA’s image and role. The selection that concerns bombing of North Vietnam’s dams and levees would represent the censors’ intervention in an historical controversy.

The most straightforward application of secrecy doctrines is represented in several of the possibilities, specifically the identification of a particular CIA document, the mention of a defector as a source for another CIA report, the mention of a National Security Agency (NSA) secure communications system, and that of the NSA telephone intercepts of Soviet leaders. In each of these cases the claim to secrecy has been mooted by the passage of time, the declassification of other records that do not form parts of the Pentagon Papers, or the fact that American adversaries already knew of the relevant information.

I offer two selections as my best guesses for the 11 Words. First is the possibility the CIA is continuing to try and disguise its 1955 involvement with Diem. This is inconvenient in that it reveals the Agency laying the groundwork for a course that would later diverge from official policy, calling its responsiveness to authority into question. My second possibility concerns the NSA equipment, mainly because that organization has a tendency toward reflexive secrecy, and likely paid little attention to having previously released the same information.

One aspect of this 11 Words business is that whoever sought to suppress the information must have had some expectation that preserving secrecy was actually possible. This would seem to rule out any material that appears in the Gravel edition of the Pentagon Papers. As it turns out, nine of eleven of these items—including the NSA equipment—do indeed figure in the Gravel edition. There are two exceptions. One is the mention of NSA radio telephone intercepts, but this has been public since 1978 and was published in 1983. The only exclusion that did not form part of Gravel and did not appear elsewhere is the item concerning CIA machinations with Ngo Dinh Diem in Saigon in 1954-1955. I therefore conclude that the Saigon CIA material is the best candidate for the 11 Words. It appears in Book 10 of the HASC edition of the Papers at page 812.

What these suggestions show above all is the arbitrary and even silly operation of the secrecy system. In case after case the censors would have been protecting information the disclosure of which threatens no damage to the national security of the United States—the actual criterion for classification. Any damage would have occurred in 1972 when these materials were published. It did not. Furthermore, Agency image and interests do not equate to the national security of the United States. Excisions that attempt to minimize the attention that might be drawn to aspects of the history of the Vietnam war that now seem embarrassing, controvert self-image, or seem inconvenient in the light of current political debates should not be taken for national security secrets that merit protection.