Washington, D.C., February 11, 2019 – U.S. intelligence analysts and Tehran-based diplomats struggled to come to grips with the tumult of the Iranian revolution, yet still managed at times to provide considerable detail for policymakers, according to a survey of formerly classified records posted today by the nongovernmental National Security Archive.

Public understanding of the intelligence community’s role in 1978-1979 when the revolution was at its peak centers around the presumption of a massive “failure” to grasp the crisis and particularly to predict the overthrow of long-time U.S. ally Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and the rise to power of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

A deeper dive into the available record, including a major, formerly Top Secret internal assessment, shows that while major failures certainly occurred, analysts and frontline diplomats filed a number of detailed reports on the political state of play, including the nature and importance of the Shiite religious opposition, that simply may not have penetrated the top levels of decision-making in Washington.

_________________________________________________

Intelligence Reporting on the Iranian Revolution:

A Mixed Record

By Malcolm Byrne

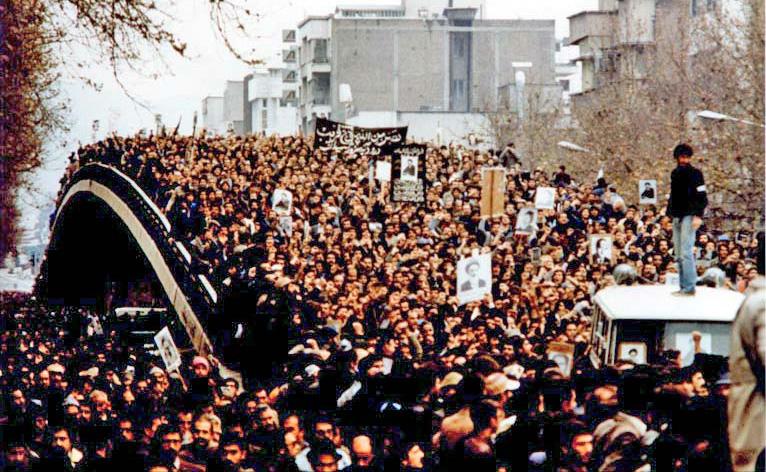

Forty years ago today, February 11, 1979, Iran’s Islamic revolution culminated in the ascension to power of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The overthrow of Iran’s monarchy and its replacement by a regime that would become deeply antagonistic to American interests was a powerful shock to official Washington and helped number the days of Jimmy Carter’s presidency.

It also shone a harsh light on the U.S. intelligence community which had the responsibility of anticipating precisely this kind of upheaval around the world, especially in a region as vital as the Persian Gulf, yet in key respects failed.

Today’s brief posting by the National Security Archive consists of some of the classic analytical reports and findings, as well as several that are far less known, prepared by various elements of the U.S. government on the subject of Iran as the revolution crested in early 1979. Their value today is as a reminder of the unpredictability of events in volatile regions and the finite ability of large and sophisticated intelligence apparatuses to foresee what lies ahead, even in the near term.

The Iranian revolution had implications that went far beyond U.S. foreign policy. The establishment of the Islamic Republic now arguably ranks among the most momentous political events of the late 20th century. Yet it took some time for this larger significance to be recognized. For months after the tumult of the Shah’s ignominious departure in mid-January 1979 and Khomeini’s arrival from exile two weeks later, U.S. officials tended to believe that either Washington could come to terms with the new regime or that it would soon collapse and business could return to “normal.”

Even so, the political knives were quick to come out and charges of a mammoth intelligence failure were leveled at the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and its fellow intelligence entities. Among the early accusations was that the Carter administration’s decision to cut back on so-called HUMINT intelligence capabilities (in the wake of CIA abuses revealed by the press in the mid-1970s) had crippled the country’s ability to see over the horizon and prepare for crises around the world.

Later, critics of unstinting U.S. support for the authoritarian Shah pointed to the fact that Washington had for some time caved to his demand that American intelligence maintain no contacts with Iranian opposition elements – based apparently on the Shah’s memories of the CIA’s role in fomenting coups such as the one in 1953 that had restored him to power.

As with many instantaneous assessments, especially in a politically charged context, these have turned out to be somewhat incomplete. Although there is considerable truth to the explanations above, the reasons for the failure to anticipate, much less prevent, the 1979 revolution were more nuanced and complicated, as the vast current literature on Iran, U.S. policymaking, and the intelligence profession itself attest. (See also Document 12 below)

For one thing, while the records in today’s posting make it clear Western intelligence was wildly off the mark in forecasting some of the big-ticket issues, such as the stability of the Shah’s regime, and were critically uninformed about details of the religious opposition, there was also reporting from the Embassy in Tehran and from the intelligence community that gave – to anyone in government who wanted to know – solid historical context for, and fairly fine-grained assessments of, events as they were unfolding.

Perhaps even more crucial, there are indications that a large part of the problem was that this reporting never made it into the hands of top policymakers, or was simply ignored. For example, former State Department Iran specialist Charles Naas has pointed out that one of the mundane but significant explanations for this is that much information was sent to Washington as Airgrams or in other low-level forms that would not normally have risen to the attention of senior officials.[1] It is also the case that other global priorities – U.S.-Soviet relations and SALT II, the Middle East peace process, the Horn of Africa, and others – loomed larger than Iran until the eleventh hour. An important reason for this was the persistently rosy view in Washington over a number of years that the Shah could handle things by himself.

Today’s posting ends with a major, declassified, 186-page study of how U.S. intelligence “failed” on Iran. It was written in Spring 1979 primarily by political scientist Robert Jervis while he was a consultant for the National Foreign Assessment Center at CIA and offers a variety of nuanced points of analysis as well as lessons for the future (see Document 12).

[Note: Later in 2019 the National Security Archive will publish a 2,500-document collection of declassified materials on the United States and Iran from 1979-2015. It will be part of the Digitial National Security Archive series through the academic publisher ProQuest.]

Read the Documents

Document 01

Freedom of Information Act request

The Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) is the State Department’s intelligence analysis branch. This report written two years before the Shah’s ignominious exile from his homeland – his second in 25 years – opens: “Iran is likely to remain stable under the Shah’s leadership over the next several years ... The prospects are good that Iran will have relatively clear sailing until at least the mid-1980s.” The subsequent analysis reflects the common assumption at the time that Iran’s leader, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was fully capable of handling any political unrest that might occur: “The Shah ... has become increasingly self-confident over the past decade...” This notion has since been widely refuted by former U.S. officials, especially those who dealt with the Shah in the turbulent 1950s. While that assessment is more subjective and harder to pin down, the authors’ flat assertion that the monarch is “in fine health” was simply wrong. Unbeknownst to the Americans (or most anyone else) the Shah had lymphatic cancer, which would eventually kill him in July 1980.

Document 02

This background report from the Embassy in Tehran to the State Department provides some useful historical background on dissent in Iran as context for new information about how the regime was handling current expressions of public disapproval. Some historians and former officials have noted that the Shah seemed to want to make a point of showing the incoming Carter administration that his government took human rights seriously. Promoting human rights was a high political priority for Carter and the Shah by most accounts saw this demonstration as a necessary but loathsome burden. He hated interference from outside, not least the sort of pressure for reform he had faced from previous Democratic presidents Kennedy and Johnson, which he considered patronizing in the extreme. He expected the same from Carter. Typical of assessments at the time, the authors of this telegram chose to see a rosy future in this regard. While dutifully hedging their predictions, they allowed themselves to conclude that “the door of liberalization seems to be ajar.”

Document 03

This fascinating analysis of the political and social force that would come to dominate the revolution is one indication that line officers in Iran were well aware of the Shiite phenomenon in the country at an earlier time than is sometimes assumed. Ayatollah Khomeini is specifically named as the “symbolic leader” of the revolution. The Embassy’s staff admits they have been “laboring” to get a better understanding of the “renascent Shi’ite religious movement” and they make plain that part of the problem is that Iranians within and outside of the government have consistently “peddled” the view that “Khomeini’s followers are for the most part crypto Communists or leftists of Marxist stripe.” The telegram goes on to give a brief survey of Shiism and Iranian monarchical mistreatment of the “Islamic establishment,” presumably in an attempt to educate non-specialists higher up in the Department. The telegram specifically advises that “it has become obvious that Islam is deeply imbedded in the lives of the vast majority of the Iranian people.”

Document 04

“The Carter Administration and the Arc of Crisis: Iran, Afghanistan and the Cold War in Southern Asia, 1977-1981,” briefing book for conference prepared by the National Security Archive

The Defense Intelligence Agency, whose primary audience consisted of the secretary of defense, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and military commanders, produced this unclassified primer on Shiism in Iran. The DIA had its own HUMINT sources overseas but this document clearly derives its information from open sources and indeed contains nothing that an interested citizen could not easily have found in a public library. But the topic indicates at least a basic recognition of the importance of one of the key dynamics at work in Iranian society. The extract posted here, all that appears to exist (and one of the few available DIA documents from the period), does not attempt to forecast the course of events in the country.

Document 05

A further indication of the extent of the religious component of public opposition comes through in this Embassy report. The telegram, by noted Iran specialist Charles Naas, describes some of the internal jockeying among senior clerics as unrest grows in the country, but also points to the supremacy of Ayatollah Khomeini who “retains an almost mystic respect” among the “mass of illiterate population.” The problem with religious demonstrations is bad enough that Naas reports the Shah is “depressed” to the point of ordering the military to break up future protests and authorizing the use of live ammunition. The source of the information in this airgram also raises two other issues that would prove to be critical in this period. One is the Shah’s health, which the source says is good although he acknowledges that medical tests have been arranged and that some of the Shah’s circle are concerned by his recent absence from public view. The other issue is corruption, long known to be a problem but subject to minimization for years by American policymakers.

Document 06

This draft of a National Intelligence Estimate that would have been prepared with input from the relevant intelligence agencies, provides substantial detail about the internal political situation in Iran. It paints a gloomy picture of the Shah’s chances and at least allows for the possibility that the Pahlavi “dynasty” may not survive the next several months without major concessions. The study also points out for the careful reader (on page 9) that Ayatollah Khomeini, “the most influential leader” of the Shiite clergy, has “for years” called for the ouster of the Shah and “the establishment of a theocracy.” It is unclear whether a final version of this NIE was prepared and circulated to policymakers.

Document 07

Freedom of Information Act request

As late as October 1978, there is still little sense in Washington or other Western capitals that things are heading in a dangerous direction in Iran. In a meeting with British counterparts earlier in the month, State Department Iran specialist Henry Precht gave a lugubrious forecast for the Shah and for Western interests but according to records of the session (click here) the British – and even Precht’s superiors – thought he was well off target. In this telegram from the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, an equally dire report directs the State Department’s attention to a visible change in attitudes across many sectors of public opinion. Pro-Shah and anti-Shah elements alike reportedly agree that his apparent lack of firm action is making the situation worse and he is in danger of losing control of events.

Document 08

Just a few days after the previous cable expressing a general sense of a worsening atmosphere in the capital, the Embassy in Tehran focuses this report on the specific question of a “military option.” The general sense seems to be that a military takeover is inevitable and many Embassy contacts – especially senior military officers – are actively supporting the idea. Many Iranians evidently believed later that the Carter administration eventually backed a military coup, which never took place. Noting that the Shah told Ambassador Sullivan personally that he was considering a military government, the telegram assesses that such a move could succeed but stops short of supporting it, concluding “the long-term costs would be heavy.”

Document 09

Freedom of Information Act request

This cable from Ambassador William Sullivan has been called one of the most important documents of the entire revolutionary period (Gary Sick, All Fall Down, p. 81). Sullivan was a long-standing proponent of supporting the Shah, which made the contents of this message, sent Eyes-Only to the secretary of state, all the more surprising to those who eventually read it, including President Carter. In it, Sullivan describes the dramatically Shah’s reduced standing in Iranian society; only the military seem to offer continued backing for him. Then in the course of a somewhat scrambled discussion, he lays out a possible scenario of events that, in sum, suggests that it might not be a bad thing if the Shah were to leave the throne. Despite its circuitousness – and the president’s exasperation at the perceived sudden change in Sullivan’s thinking – the cable is credited with having a significant influence on U.S. policy.

Document 10

“The Carter Administration and the Arc of Crisis: Iran, Afghanistan and the Cold War in Southern Asia, 1977-1981,” briefing book for conference prepared by the National Security Archive

This report’s main value historically is as a sign of the level of frustration President Carter felt at the inability of his advisers to come to a consensus on Iran. In late November 1978 the president commissioned veteran Washington policy adviser George Ball to come up with an independent assessment of events and a set of policy proposals. Ball predicted the Shah could not survive in his present role. He also argued against a military solution and for reaching out quietly to Khomeini. As for a new government, he thought the Shah should establish a Council of Notables, with members approved by the U.S., that would identify a way to transfer power to a responsible entity. The memo ultimately had virtually no impact. Carter told Ball, among other things, that he could not tell another head of state what to do. According to Iran scholar James Bill, who interviewed Ball, National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski was instrumental in quashing the ideas in the report.

Document 11

Freedom of Information Act request

While not an analysis like the other documents in this posting, this exasperated telegram from Ambassador Sullivan to Secretary of State Cyrus Vance reflects the intensity of emotions among U.S. officials at this fraught stage of the revolution. In extraordinarily blunt language, Sullivan accuses President Carter of making a “gross and perhaps irretrievable mistake” by failing to dispatch an intermediary to meet with Ayatollah Khomeini, as Sullivan notes was previously agreed. The issue of whether to contact the leader of the religious opposition was broached repeatedly by officials in the final lead-up to the uprising and focuses attention on one of the underlying problems with U.S. (and Western) approach to relations with Iran under the Shah.

Document 12

Freedom of Information Act request; also available on CREST

So disconcerting was the Iran debacle in early 1979 that Robert R. Bowie, then head of the National Foreign Assessment Center (NFAC) commissioned a report on how the intelligence community fell so far short. The principal author was political scientist Robert Jervis, who was at the time a visiting consultant to NFAC. The report goes into great detail and provides both nuance and enormous grist for specialists on the wider problem of intelligence failure. In the case of the Iranian revolution, the report examines the question of failure on at least three levels: from the gathering and handling of specific pieces of intelligence to broader problems of preconceptions about Iran under the Shah to the weaknesses in NFAC’s analytical system. Jervis later incorporated the report along with other internal documentation and an entire section on the later Iraq war into a book, Why Intelligence Fails: Lessons from the Iranian Revolution and the Iraq War (paperback, Cornell, 2011)

Note

[1] Charles Naas in “The Carter Administration and the Arc of Crisis: Iran, Afghanistan and the Cold War in Southern Asia, 1977-1981,” conference co-organized by the National Security Archive and the Cold War International History Project, Washington, D.C., July 25-26, 2005.