Washington, D.C., December 8, 2016 - A CIA-sponsored panel of well-respected scientists concluded that a mysterious flash detected by a U.S. Vela satellite over the South Atlantic on the night of 22 September 1979 was likely a nuclear test, according to a contemporaneous report published today for the first time by the National Security Archive and the Nuclear Proliferation International History Project.

Within days, a larger White House scientific panel would assert that the nuclear test thesis was unlikely, but in 1980 additional evidence emerged that led a senior U.S. intelligence official to disparage the White House study as a “whitewash” influenced by “political considerations.”

The debate over the “September 22 Event” or the “South Atlantic flash” continues to this day, including whether Israel may have staged a test with South African assistance. The newest information, included in today’s posting, comes from recently declassified documents in the files of Ambassador Gerard C. Smith at the National Archives. The Smith files shed light on both the Vela controversy and the U.S. government’s efforts to grapple with it.

New Evidence on 22 September 1979 Vela Event

William Burr and Avner Cohen, eds.

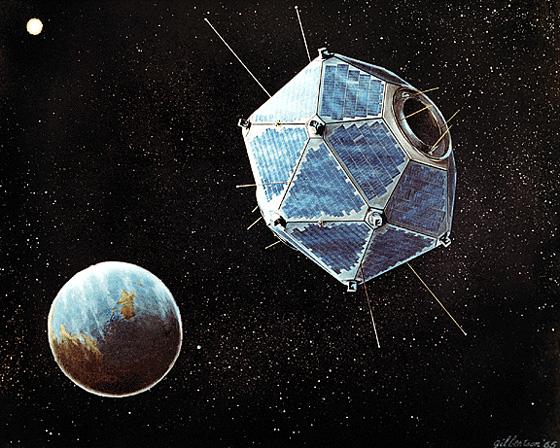

On the night of 22 September 1979, a U.S. Vela satellite, designed and used for spotting nuclear tests, detected a flash that the U.S. Intelligence Community located somewhere in the South Atlantic area. According to the October 1979 findings of a CIA-sponsored panel of well-respected scientists, published today by the National Security Archive and the Nuclear Proliferation International History Project for the first time, the Vela “signals were consistent with detection of a nuclear explosion in the atmosphere.” A scientists' panel convened by the White House would find the nuclear test thesis unlikely, but additional evidence emerged later in 1980 that raised questions about that panel’s findings. Citing hydroacoustic data characteristic of an oceanic nuclear event, Jack Varona, a senior official at the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) argued that the White House panel’s report was a “whitewash, due to political considerations.”

The debate over the “September 22 Event” or the “South Atlantic flash” continues to this day. Whether the Vela satellite captured a low-yield nuclear test, most likely staged by Israel possibly with South African assistance, or whether the data reflected some sort of technical malfunction or a reflection of natural non-nuclear phenomena has been at the center of the controversy. The debate remains open, somewhat inconclusive, although new information and analysis has emerged supporting the view that the Vela data originated in a test. These authors side with this view.

Some of the new evidence is cited below in this essay. The latest information, the key parts of this posting, comes from recently declassified documents in the files of Ambassador Gerard C. Smith (1914-1994) at the National Archives, which shed light on both the Vela controversy and the U.S. government’s efforts to grapple with it. Besides the memorandum on the CIA panel, and Varona’s statement, Smith’s papers also include the following noteworthy items:

- In 1977, Washington was concerned about the possibility of Israeli-South African nuclear weapons cooperation, but Prime Minister Menachem Begin denied any such cooperation existed, while evading questions about other forms of nuclear cooperation. President Jimmy Carter decided that “we shouldn’t push [the issue] any more for now.”

- In a letter that Richard Garwin wrote on 19 October, several weeks after the Vela flash, he maintained that “on the basis of the information which we obtained and the analysis we were able to do, I would bet 2 to 1 in favor of the hypothesis” that the incident was a nuclear explosion. He later changed his mind.

- State Department telegrams from November 1979 reviewed efforts by New Zealand scientists who had reportedly detected small amounts of fall-out in rain water; the initial analysis was found to be a “false alarm” and an official with the Air Force Technical Applications Center (AFTAC) secretly confirmed that the data was “flimsy.”

- The State Department produced a series of memoranda from September and October 1979 on diplomatic strategy in the event that reports of the Vela flash leaked (which they did) and how to approach the South African government

- State Department telegrams from February 1980 dismissed information from MIT professor Jack Ruina, gained from an Israeli visiting fellow at MIT, concerning a possible Israeli connection to the 22 September event.

- A State Department memorandum recounted Varona’s findings that hydroacoustic data of sounds carried through water, captured on 22 September 1979, reveal signals “which were unique to nuclear shots in a maritime environment.” The U.S. Naval Research Laboratory had analyzed the data and determined that the source of the sound was the Prince Edward Islands, controlled by South Africa, in the vicinity of the sub-Antarctic Indian Ocean.

As U.S. representative to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and ambassador-at-large as well as U.S. special presidential representative for non-proliferation matters, Gerard C. Smith played a central role in the development of the Carter administration’s policy to halt the spread of nuclear weapons. His papers are a cornucopia of declassified records on a range of issues, from the Pakistani nuclear program and India’s Tarapur reactor to nuclear sales to Argentina and the development of safeguards policy. The Smith file enables us to revisit the Vela event afresh.

A few documents in this posting are from the Jimmy Carter Library; they add some context and texture to the materials in the Smith file. However, two major files in the Carter Library on the 22 September event remain classified, although they have been requested for declassification review. Their release should provide a fuller picture of the Carter White House’s reaction to the Vela affair, including the role of National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski.

The Vela Flash: Story of a Mystery

Initial thinking about the 22 September event leaned heavily toward a nuclear test interpretation. IBM’s Richard Garwin, along with many government scientists and intelligence analysts, originally shared that view. However, while on the White House panel Garwin shifted his thinking; he supported the panel’s conclusion that a nuclear test was unlikely.

From the very start the Vela issue was a tricky one, technically and politically. On the technical side, when scientists considered the Vela signals, they had to address certain peculiarities and anomalies: corroborative radioactive fallout could not be detected; the double flash signal had certain atypical characteristics; questions emerged about the reliability of the instrumentation on the ten-year-old Vela 6911 satellite, which was already more than two years beyond its “design lifetime." Air sampling missions in the Southern Hemisphere conducted by the Air Force Technical Applications Center (AFTAC) had been unproductive and records of seismic activity failed to provide positive information. The prospect that fission products had been detected in rain water in New Zealand proved to be a false alarm.

Furthermore, even if the Vela signal proved to indicate a nuclear test, no smoking gun was available that could attribute it to Israel or South Africa or any other state. Hence, what President Jimmy Carter wrote in his diary on that day of September 22, 1979 -- which became publicly known in his 2010 diary book -- reflected well the complexity of the situation: “There was indication of a nuclear explosion in the region of South Africa—either South Africa, Israel using a ship at sea, or nothing.”[1]

On the political side, the Carter administration had much at stake on the issue of the Vela flash, which eventually leaked to the media in late October 1979. Had it been confirmed that it was a nuclear test, and that South Africa and/or Israel were prime suspects, significant diplomatic complications would ensue. That was particularly so in the case of Israel, not least because the very existence of its nuclear program was a political taboo in Washington, something never to be acknowledged. Admission that Israel and South Africa had tested a bomb could unravel President Carter’s most important international legacy – the peace treaty he just had negotiated between Egypt and Israel, signed only six months earlier at the White House. And to impose sanctions against Israel for violating U.S. nonproliferation legislation and the Limited Test Ban Treaty would have been a political catastrophe. The aversion to even identifying the test as a nuclear event was so intense that Leonard Weiss, a scientist and nonproliferation expert on the staff of Senator John Glenn (D-OH), recalls that at a briefing a senior State Department official told him “that if I continued to say that the Vela event was a nuclear test, my reputation would be destroyed.”[2]

The diplomatic problems that would be raised by certainty about a nuclear test would fade away if distinguished, non-governmental scientists concluded that the Vela signals had a likely non-nuclear explanation. Richard Garwin, who had already suggested (in a letter to ACDA Deputy Director Spurgeon Keeny) that experts investigate non-nuclear “real phenomena,” and Frank Press, the director of the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy, were already thinking along the same lines (quite possibly influenced by some senior members of the Carter administration). In any case, in late October Press appointed a blue-ribbon panel of eight distinguished scientists to make a technical evaluation of “whether or not a nuclear explosion occurred in the South Atlantic on September 22, 1979.” Already aware that the Vela satellites were deteriorating and producing false signals, Press limited the scope of the new White House panel to purely technical aspects, i.e., to investigate whether the signal had “natural” causes and to evaluate the possibility that it was a “false alarm.” Press chose Jack Ruina, a friend of his who was a well-respected professor of electrical engineering at MIT and a former director of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) at the Pentagon, to lead the panel.

The Ruina panel started its work on 1 November 1979, held two classified plenary sessions, and by January 1980 had reached tentative conclusions. The panel “was unable to determine whether the light signal recorded by the satellite was generated by a nuclear explosion or some other phenomenon.” After reviewing alternative natural phenomena which might have caused the flash, the panel suggested the signal was the result of “the possible reflection of sunlight from a small meteoroid or a piece of space debris passing near the satellite” [See Document 30]. In the spring it completed and submitted its classified report, in which it concluded that the Vela signal “was probably not from a nuclear event,” a deduction that panel member Wolfgang Panofsky later referred to as a “scotch verdict,” that is, that a nuclear event was not proven. The Ruina panel believed that it was “more likely that the signal was one of those so-called “zoo events,” i.e., unexplained events, possibly a consequence of the impact of a small meteoroid on the satellite.” Richard Garwin, an important member of the panel, signed off on those conclusions even though as noted he had been an early proponent of the nuclear test interpretation. To this day we do not know exactly why, how, or when Garwin changed his judgement about the Vela event.

The Ruina panel’s tentative conclusions notwithstanding, Jimmy Carter wrote in his diary on 27 February 1980 that “We have a growing belief among our scientists that the Israelis did indeed conduct a nuclear test explosion in the ocean near the southern end of South Africa.”[3] Not surprisingly, the Ruina panel’s conclusions, which angered many within the intelligence community, did not dampen further analysis and investigation by intelligence officials and government scientists. Indeed, intelligence community insiders as well as scientists at Los Alamos and Lawrence Livermore National Labs and the Naval Research Laboratory rejected the “zoo event” conclusion and sought new evidence that the event had been a nuclear detonation. A December 1979 interagency intelligence study issued entitled “The 22 September 1979 Event,” previously released to the National Security Archive in different excised [Version A and Version B] began with the assumption that the 22 September event was a nuclear explosion, even though “we cannot determine with certainty” its nature and origin Years later, the former director of the CIA, Admiral Stansfield Turner, told one of these authors (AC) during the 1990s that he never took the Ruina panel seriously and had always supported the prevailing view among the Agency’s analysts that the double flash was a nuclear test, most likely conducted by Israel. He did not go into detail.

Whether Vela 6911 captured a low-yield nuclear test, or whether the data reflected some unexplained “zoo” event in space has been one of the mysteries of the nuclear age. In the absence of new empirical evidence or new technical findings, the debate over the Vela mystery appeared stalled. This was the state of affairs when our colleague Jeffrey Richelson put together in May 2006 the first Electronic Briefing Book on the subject of the Vela 6911 mystery in an effort to illuminate the scientific state of the controversy by introducing all the available declassified government reports. The tone of that EBB, as well as his account of the state of the controversy in his Spying on the Bomb: American Nuclear Intelligence from Nazi Germany to Iran and North Korea was meticulously neutral and respectful to both sides of the controversy. Richelson did not try to resolve the mystery, but rather to present it accurately.

In the last few years, however, the debate over the South Atlantic flash has shifted. A body of new evidence has challenged the conclusions of the Ruina panel. The most prominent Advocate of the new outlook is Leonard Weiss, who served for many years as the chief of staff on the Governmental Affairs Committee chaired by Senator Glenn, and has presented his interpretation in a number of new publications. An important part of his findings draws on technical analysis by a scientist at Los Alamos national laboratory suggesting that the Vela satellite sensors worked correctly.[4] In addition, there is now also more knowledge (although still largely fragmentary and circumstantial) about the scope and depth of Israeli-South African nuclear cooperation before and during the 1970s. Moreover, there is also a better understanding of the state of the Israeli nuclear program after the 1973 Yom Kippur War and why Israel may have found it worth taking the risk of staging a secret test.[5] All these points lead Weiss to make the case that it was Israel, possibly with some logistic assistance from South Africa, that conducted the test.

Identifying Culprits

Against these developments, this Electronic Briefing Book brings to the debate newly declassified archival material from the files of Gerard C. Smith. Documents in Smith’s files highlight that initially the consensus view was that the event was likely a nuclear test, which induced officials at the State Department and the White House to ponder the diplomatic and security implications, especially for U.S. nuclear nonproliferation policy and for U.S. policy towards Africa. From the very beginning, apartheid South Africa was a major suspect because it was the only state in the South Atlantic area that was on the threshold of having a nuclear weapons capability. Ever since August 1977, when the Soviet Union had detected what appeared to be a nuclear test site in the Kalahari Desert, information that U.S. intelligence soon confirmed, the Carter administration had been trying to roll back South African suspect nuclear activities and persuade Pretoria to sign the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. These developments are richly documented in a recently published volume in the State Department’s Foreign Relations of the United States series.

Not surprisingly, the South African government privately and publicly denied any knowledge of a nuclear test and ridiculed reports that it was responsible for the 22 September event. South Africa remained a widely discussed “culprit,” but the possibility of an Israeli test or even a joint Israeli-South African effort also had significant cachet. Israel was known to have an ongoing nuclear weapons program but had not been known to stage any tests. The reason why South Africa was initially the most widely discussed culprit, while Israel was less mentioned, had much to do with both the taboo-like sensitivity of the Israel nuclear program and the fact that so little was known about it, even among top U.S. diplomats. However, within the U.S. nuclear intelligence community it was well understood, even at that time, that the level of South African nuclear expertise was simply insufficient to produce the kind of low-yield event that was apparently detected by the Vela. At the same time, it appears that only few within the U.S. intelligence community understood the technological status of the Israeli nuclear program after the 1973 war, and the kind of technical hurdles it faced. Apparently, the Vanunu revelations of 1986 were an eye-opener for U.S. intelligence experts, but how much they knew before 1986 remains classified.[6]

The recently published FRUS volume sheds some light on the Israel-South Africa nuclear connection. Two years earlier, at the time of the flap over the Kalahari test, State Department and White House officials, among others, became concerned about the possibility of Israeli-South African nuclear cooperation. U.S. intelligence was aware of ongoing technical and scientific exchanges, even as early as in the 1960s when South Africa had supplied Israel with “a small quantity of natural uranium.” The cooperation had been highly secret: apartheid South Africa was a pariah state globally and Israel, given its problematic position in the Middle East, wanted to avoid further opprobrium. The Israelis had categorically denied any such cooperation and it was unclear to U.S. intelligence whether the two states had actually cooperated in nuclear weapons research and development. The FRUS documents show that Washington sought to learn more from the Israelis but was rebuffed. Since then more information about the history of Israeli-South Africa nuclear cooperation has surfaced, although hard evidence on weapons cooperation is scarce.[7]

As noted earlier, the intelligence community explored various possibilities, most prominently a test by Israel, or an Israeli-South African joint venture, and even secret tests by India, Pakistan, and the Soviet Union. The previously cited interagency intelligence report from December 1979 and released in different versions over the years [Version A and Version B] considered such possibilities, but its conclusions implied a South African test, although leaks to the media suggested that the CIA was looking very closely at Israel.[8] Other major reports remain classified, such as the February 1980 report by the Nuclear Intelligence Panel to Director of Central Intelligence Stansfield Turner. The substance of the DIA’s June 1980 report is also classified, as is a report by the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) from the same month. These reports are all under declassification review, including several that are before the Interagency Security Classification Appeals Panel (ISCAP).

Documents in the Smith files indicate how the Israeli-South African connection resurfaced in the wake of controversy over the Vela incident. Telegrams from the U.S. Embassy in Israel discuss a CBS Evening News report on 21 February 1980, based on an exclusive report by Tel Aviv based CBS correspondent Dan Raviv, saying that CBS had learned that the Vela event was indeed an Israeli test. The report cited an Israeli book manuscript titled None Will Survive Us: The Story of the Israeli Atom Bomb by journalists Eli Teicher and Ami Dor-On (their book was never published as it was banned by Israeli censors).[9] Subsequently journalist Raviv told one of us (AC) that in addition to the book he had another high-level and reliable Israeli political source, Eliyahu Speiser, an Israeli politician who served as a member of the Knesset for the Labor Party between 1977 and 1988 (died in 2009), who confirmed the story about an Israeli nuclear test. Raviv had reported his story from Rome to evade Israeli press censorship and subsequently lost his press credentials for his censorship offense on direct order from the Israeli Minister of Defense, Ezer Weizman.

State Department telegrams in Smith’s file also confirm that in February 1980 MIT Professor Jack Ruina received personal information from an Israeli source that seemed to support the view that the Vela event was indeed an Israeli test. The telegrams do not provide any detail as to the identity of that Israeli or the content of his information but in Seymour Hersh’s The Samson Option’s there is a reference to this episode. According to Hersh’s account, an Israeli missile expert was a visiting fellow at that period at MIT’s Defense and Arms Control Studies (DACS) Program (which Ruina had founded and directed). Unnamed by Hersh, but based on MIT publications, that missile expert was Dr. Anselm Yaron, a senior missile engineer, who had been the head of the Israeli Jericho missile program during the 1970s (see previous footnote). According to those publications, Yaron joined Ruina’s research team on a project, funded by a grant from ACDA, involving an assessment of a major nuclear/missile proliferation concern: specifically, the extent to which civilian technology for missile propulsion and guidance could be adapted for military applications. According to Hersh’s account, Yaron enjoyed talking openly about his defense experience and told Ruina about his work on Israel’s missile program and also about his knowledge of Israel’s nuclear capability.[10]

Hersh did not say how explicit and exact Yaron was about what he told Ruina, but he implied that Yaron had suggested to Ruina that the September 22 flash was a joint Israeli-South African operation. Also, according to Hersh, Ruina forwarded Yaron’s information in a report to Spurgeon Keeny at ACDA. Nevertheless, Keeny was dismissive of the story, as was Frank Press’s executive secretary, John Marcum (See Document 36B). Some of Hersh’s basic tale was confirmed to us (AC) by an individual who got to know Yaron during his time at MIT. Our interlocutor specifically recalls Ruina giving a talk at MIT on the unclassified version of his panel's report indicating that test was unlikely and that during the discussion Yaron commented on the conclusions: “don't be too sure."

At the close of the 1980s, Gerard C. Smith commented that “I have never been able to get rid of the thought that [the 22nd September event] was some sort of joint operation between Israel and South Africa.”[11] The new documents from this file do not settle anything in that respect, but they underline the importance of getting more information declassified; for example, the hydroacoustic data cited in Document 37 indicates the importance of the Naval Research Laboratory report. Nevertheless, the Smith file sheds light on significant aspects of the 22 September event, by adding to our knowledge about Carter administration policy toward the incident, including diplomatic considerations and initiatives, consultations with allies, the role of scientists, and the controversy over the Ruina report. It is also worth noting that sixteen documents in the Smith file remain classified. Pending declassification requests for these documents, for relevant files at the Jimmy Carter Library, and other significant records may expand knowledge about the Vela incident.

Editors’ note: Except for Documents 1A and B, 33, and 41, all documents that follow are from the files of Gerard C. Smith at the National Archives. Unless otherwise indicated, all are from box 8, Mexico. That file includes documents on the 22 September event, while a specific file on the 22 September event in the same carton includes unrelated material. At some point, perhaps when they were in the State Department’s custody, the papers became seriously disorganized.

*Thanks to Jeffrey Lewis, Marvin Miller, Jeffrey Richelson, and Leonard Weiss for their helpful comments and to Kai Bird for providing copies of documents from the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library.

I. Israel and South Africa

Document 1A-B: Israeli Denials

Document A: Telegram from the Department of State to Secretary of State Vance and Multiple Diplomatic Posts Repeating Tel Aviv Embassy Telegram 6330, 24 August 1977, Document 304, U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1977-1980: Volume XVI Southern Africa

Document B: State Department telegram 213320 to U.S. Embassy Tel Aviv, “Possible Israeli-Israel South African Connection,” 7 September 1977, Secret

Source: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library, National Security Adviser Files, NLC-16-108-2-13-9

Documents in the Foreign Relations volume on Southern Africa provide fascinating evidence on the controversy over the Israeli-South African nuclear connection.[12] While they indicate that U.S. intelligence had evidence of some nuclear cooperation, if no hard data on nuclear weapons cooperation, the White House and the State Department were concerned enough to seek assurances from the Israelis that they were not collaborating with South Africa in developing nuclear weapons. Moreover, Washington sought “full and complete information from the Government of Israel on the nature of any Israeli/South African cooperation in the nuclear field.” When U.S. ambassador to Israel Samuel Lewis made the request to Foreign Ministry Director General Ephraim Evron, the latter would only affirm that his government “has no contact nor has it ever cooperated” with South Africa in developing nuclear weapons or explosives. This is the first – and probably the only instance – in which an Israeli diplomat categorically affirmed, in the name of the Prime Minister, Menachem Begin, that Israel had not engaged in collaboration with South Africa on any aspects of weapons design, what is often referred to as weaponization. At the same time, the Israeli official evaded, effectively refusing, the U.S. request for “full and complete information … on the nature of any Israeli/South African cooperation in the nuclear field.” Since then South African sources have confirmed that Israel and South Africa were engaged in the exchange of nuclear materials – Israel received natural uranium (yellow cake) from South Africa and provided South Africa with a small amount of tritium.

In early September 1977, with more intelligence information at hand about Israeli-South African nuclear cooperation, the State Department was especially concerned about “loopholes” in the assurances made by Begin and Evron, such as the possibility of indirect cooperation, technology transfers, or cooperation in the testing of a device. Therefore, the Department directed the Embassy in Tel Aviv to “seek further clarification” on those matters not only to see if anything could be learned but also to induce Begin to strengthen his “assurances so as to close off all avenues of potential cooperation.”

Document 2: Memorandum from National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski to the Secretary of State, “Possible Israeli-South African Nuclear Connection,” 13 September 1977, Secret, with handwriting by Gerard C. Smith and his deputy Philip J. Farley (PJF)

Source: Smith records, box 20, South Africa II

The implication from this note from national security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski to Secretary of State Cyrus Vance is that a telegram from Ambassador Lewis (which is still classified) may have indicated that further efforts to elicit more information from the Israelis about their nuclear relations with South Africa had been unsuccessful. When President Carter read the ambassador’s telegram, he instructed Brzezinski to give up on the effort to obtain information about “past [nuclear] cooperation” between Israel and South Africa. Further, “we shouldn’t push [the issue] any more for now.”

Document 3: Memorandum from Gerard C. Smith to Brzezinski, “Possible Israeli-South African Nuclear Connection,” 17 September 1977, Secret

Source: Smith records, box 20, South Africa II

When Gerard Smith read the Brzezinski memorandum (Document 2), he flagged a serious problem in Carter’s decision to drop the issue of past nuclear relations between Israel and South Africa for the time being. By giving up pushing for information on the past record or on “the intentions” of the Israeli government, “should awkward past connections or future relations develop, we would find it difficult to explain why we had accepted so reserved a response. In that event, enemies of the US, Israel or South Africa could even charge us with indirect complicity.”

Document 4: Assistant Secretary of State for Politico-Military Affairs Leslie H. Gelb to Distribution List [Ambassador Gerard C. Smith et al.], “The ‘Dirty Dozen’ -- Broadening Our Approach to Non-Proliferation,” 17 March 1978, Secret

Source: Smith records, box 5. Nonproliferation Strategies

This document by Leslie Gelb on the “dirty dozen” potential proliferators is interesting partly because of what it does not say about the Israeli case. As the report was written at the secret level (not even “secret/sensitive”) it is possible that the authors could not use or did not have access to the most sensitive intelligence; they confined themselves to generalities, such as Israel’s capability to produce plutonium. They acknowledged that they lacked a “basis on which to conclude whether Israel now has nuclear weapons,” a claim which was in a sharp contrast to a 1974 intelligence community estimate that “Israel already has produced and stockpiled a small number of fission weapons." Indeed, the political bargain that President Richard Nixon made secretly with Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir – by which American leadership accepts Israel’s nuclear status as long as Israel is committed to an ambiguous and low key posture – may have been unknown to anybody in the State Department. Apparently, Henry Kissinger had briefed President Carter on it, at the request of the Israelis, but what Carter thought about the Nixon-Meir bargain is unknown.[13]

Whatever the state of the Nixon-Meir bargain was in 1978, Gelb took it for granted that the Israeli nuclear program was impervious to the rules of the nuclear nonproliferation regime. Even though he believed, or may have wished, that Israel’s dependence on U.S. aid gave Washington “extensive non-proliferation leverage,” he pointed to a number of considerations that made that leverage nugatory: “strong domestic US interests supporting Israel unequivocally,” “the clandestine character of the Israeli nuclear program,” and the “high US priority in finding a peace settlement in the area is overriding and inhibits effective pursuit of non-proliferation objectives.”

The Gelb report was better versed on the South African nuclear program: “we believe that South Africa could produce a nuclear explosive fairly quickly.” South Africa had “clear competence” in nuclear science and technology and its uranium enrichment plant at Valindaba “may be capable of producing highly enriched uranium -- the probable material for any South African device.” Moreover, South Africa was believed to have a nuclear test site in the Kalahari Desert.

Gelb reviewed the state of U.S. efforts to encourage South Africa to accept nuclear nonproliferation norms, including adherence to the NPT and safeguards at the Valindaba plant. The state of knowledge reflected by this document may explain why a year later, when the Vela event occurred, most people in the State Department and ACDA thought first about South Africa, and only second about Israel.

II. Vela Initial Response

Document 5: Allen W. Locke to Mr. Moose et. al., “South Africa,” 22 September 1979, Secret

Allen W. Locke, one of Gerard Smith’s principal aides, went to work at the State Department on a Saturday, hours after U.S. officials learned about the Vela incident. There he wrote a paper on the various options available on how the U.S. should respond to what may have been a “South African nuclear test,” for discussions to be held the next day, first at the Department and then at the White House. The degree of “certainty” of the data would determine the response: whether it could be determined that a nuclear test had occurred or not, whether it could be ascertained who staged the test, and whether it could be determined that South Africa had responsibility. If it was the latter, “Two lines of U.S. foreign policy intersect … our African policy and our global nonproliferation policy. The tendency of both is to require a strongly negative official reaction to South Africa's action.” By strongly denouncing the test and pressing for South Africa to abandon its nuclear explosives program, Washington could “eliminate every opportunity for accusations that we condone what South Africa has done.” Israel is not mentioned by name as a possible culprit.

Document 6: Memorandum for the Record by Richard M. Moose, “Current Nuke Event Actions,” 25 September 1979 [misdated 1969], Secret

Within days, Washington told close allies about the Vela secret. Apparently, the British had learned about it first because State Department officials told John Robinson, the deputy chief of mission, that they were about to tell the French and the West Germans, with the “green light” given by Gerald Oplinger (on Brzezinski’s staff). Secretary of State Vance (“CRV”) would broach the secret at a scheduled dinner of the secret Quadripartite Group [United States, United Kingdom, France, and West Germany], although Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs David Newsom (“DDN”) would tell the French officials even before then. Before the Australians were told about the Vela data, U.S. officials would ask them if their seismic monitoring stations had been turned on at the time of the incident.

Document 7: Memorandum for the Record by Allen W. Locke, “Requesting Australian Assistance in Verifying Possible South African Nuclear Test,” 25 September 1979, Secret

Later that day, the White House decided that the Australian government should be informed at the most "senior level" about the Vela findings. Otherwise, “U.S. Air Force activities conducted from Australian territory would be described on the basis of a cover story.”

Document 8: “Things to Do for the Second Contingency,” 27 September 1979, with attachments on “Actions to be Taken Should We Conclude a Test Has Occurred and the Issue Has Not Yet Become Public Knowledge,” and “Actions to be Taken Should Knowledge of Nuclear Test Become Public Domain,” Secret

The Vela story did not leak to the press until October 25, 1979, but officials at Gerard Smith’s office considered what kind of preparations and by whom should be made for that eventuality (“the second contingency”). If the administration concluded that a nuclear test, possibly by South Africa, had indeed occurred but the story had not leaked, it would have to decide what steps to take, e.g., whether to issue a public statement, introduce a United Nations resolution, consult with other nuclear suppliers, and possibly an approach the South African Government.

Document 9: Paper prepared by Lewis R. Macfarlane, Deputy Director, Office of Southern African Affairs, “Next Steps—Possible Scenarios,” 10 October 1979, Secret

With the possibility of a leak ever present, the justification for sitting on the information about the Vela incident would look less convincing because Washington could be charged with a cover-up. Still waiting for the findings of a (first) independent panel of expert scientists which had begun work on October 9 (see below), Southern African Affairs Deputy Director Lewis Macfarlane developed options for the two likely contingencies: 1) that Washington had no additional knowledge, or 2) that it could confirm that the test was South African. In the former case, the Carter administration could 1) intensify its ongoing nuclear negotiations with South Africa, but act as if nothing had happened; 2) lodge a demarche with South Africa to test Pretoria’s reactions, and 3) make a low-key public announcement and tell the South Africans at the same time. If Washington believed that the evidence pointed to a South African role, it could either make a high-level approach to Pretoria or make a public announcement. Implicit already in this document, however, is the desire that if the Vela event were due to a technical malfunction – “even, say in the 15-30 percent range” – that would still make a big difference.

Document 10: Memorandum for the Files by Ross E. Cowey, director of Strategic Affairs, Office of Intelligence and Research, 10 October 1979, Secret

Under the auspices of the CIA, three well known scientists who had long-standing associations with the U.S. government as officials and consultants reviewed the Vela data.[14] They were former director of Los Alamos National Laboratory Harold M. Agnew, Richard L. Garwin (H-bomb designer, IBM’s Watson Laboratory), and the FCC’s Chief Scientist, Stephen Lukasik (former director of DARPA and Chief Scientist, RAND Corporation). This document is a synopsis of their conclusions, not the full report. They concluded that the Vela “signals were consistent with detection of a nuclear explosion in the atmosphere,” while acknowledging that “the Vela sensor outputs were less ‘self-consistent` than usual” (a reference to the fact that the two bhangmeters on the Vela satellite did not “yield equivalent or ‘parallel’ readings for the maximum intensity of the second flash.”)[15] They also supported the collection of more data, e.g., from radioactive debris, air sampling, and ships sailing in the area. Moreover, the possibility of air and naval activity in the area should be investigated. They also noted that it was unusual to stage a test at night and that the measured yield, 1.5 to 2 kilotons, was probably lower than the yield anticipated by the designers.

Document 11: Spurgeon Keeny, Deputy Director, Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, to Ambassador Henry Owen, “Transmittal of Letter from Richard Garwin,” 19 October 1979, sending Letter from Richard Garwin to Harold M. Agnew and Stephen J. Lukasik, 18 October 1979, Secret

On 19 October, Spurgeon Keeny forwarded a letter from Richard Garwin to Ambassador-at-Large Henry D. Owen, who worked on economic summit affairs for the Carter administration but had had a long involvement in nuclear policy issues. Looking back at the report that he had done with Agnew and Lukasik on 10 October, more than a week later Garwin wrote to his two colleagues on the panel, as well as to Keeny, suggesting that the Vela event was worth continued exploration. He maintained that “on the basis of the information which we obtained and the analysis we were able to do, I would bet 2 to 1 in favor of the hypothesis” that the Vela incident was a nuclear explosion. Those were good odds and he continued to support efforts to collect more information. Garwin, however, also had an additional suggestion: “to take somewhat longer, with a perhaps larger group of technical experts, to focus in particular on the possibility that a combination of real phenomena [natural, other than nuclear] could have produced the data presented to us.” In other words, he suggested revisiting “the primary data, day by day, and not particularly at the time in question, to determine the rate of individual events which could mimic the components of the data which we saw.” To try out that approach, he recommended a one- or two-day meeting by “skeptical critical experts,” for which he suggested Richard Muller (University of California, Berkeley), Wolfgang Panofsky (Stanford University), Luis Alvarez (University of California, Berkeley) and Burt Richter (Stanford University).

Garwin did not say what exactly stimulated him to revisit afresh the findings of the CIA panel or what led him to propose a new review by expert scientists. Garwin’s suggestion may have been the germ of the idea for the special White House panel which Carter’s science adviser, Frank Press, commissioned under the direction of MIT scientist Jack Ruina. Document 31 in this collection suggests that Gerard Smith and Henry Owen made the proposal for a White House panel. More needs to be learned on this point.

Document 12: Memorandum for the Record by William G. Bowdler, Director, Office of Intelligence and Research, “Nuclear Event in the South Atlantic,” 22 October 1979, Secret INR director

In this memo, INR Director Bowdler recounted his telephone conversation with British Embassy deputy mission chief John Robinson who had told him that acoustic evidence collected at Rarontonga (Cook Islands) “had provided negative results” on the Vela incident. Robinson said his government was worried about the implications, unspecified in this memo, of a leak for ongoing talks on Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) in London.

Document 13: Gerard C. Smith to David Newsom, “South Atlantic Problem,” with discussion paper attached, 23 October 1979, Secret[16]

For a White House meeting that day, Smith recommended a number of actions once it had been concluded that all “reasonable efforts to collect and analyze additional intelligence” had been made. From his perspective, the intelligence community had “high confidence” that a “low yield atmospheric nuclear explosion” had occurred on 22 September. Believing that a damaging leak was likely, Smith wanted to get ahead of it through consultations with Congress, allies, and South Africa. Consultations with Moscow at a later stage should be considered. He also recommended a new “contingency statement” for public use in the event that a leak occurred.

Smith saw risks in public disclosure, e.g. the adverse impact on African states could create pressures for “strong action against South Africa” in the form of broader sanctions. Moreover, with respect to the negotiations over Rhodesia/Zimbabwe as well as Namibia, disclosure “would sharpen the lines already drawn.”

Like others in the State Department, Smith saw South Africa as “the most likely responsible party by virtue of its geographic location, its advanced nuclear status which includes a nuclear enrichment capability, and evidence that it has actively explored development of a nuclear explosives capability.” South Africa, for Smith, was the only “threshold state” with those characteristics, but he acknowledged the “possibility that Israel could have detonated a device in this remote geographic area.”

With the focus on South Africa, Smith recommended a demarche to Prime Minister Piet Botha, possibly in league with France and the United Kingdom, because, “without question,” he would know whether a test had occurred. Smith saw risks that a confrontation with South Africa could rupture ongoing negotiations over its nuclear program, but “failure to take action in response to the September 22 event could make more difficult efforts to deter proliferation elsewhere, e.g. Pakistan and India."

Document 14: “Nuclear Explosion Panel: Charter,” n.d., circa 1 November 1979

Smith’s file includes an undated document that may have been the official charter, or a draft of it, for the White House panel. The text mandated exploring whether a “natural phenomenon” triggered the Vela signal or whether it was a “false alarm” produced by technical failure. The directive was open-ended enough to call for a review of all data that could verify the Vela signal and to identify “any additional sources of data that could be helpful in this regard.”[17]

III. Leaks

Document 15: Gerard C. Smith to the Secretary, “Congressional Briefing on South Atlantic Incident,” 26 October 1979, Confidential

By 26 October 1979, the news of the Vela incident had leaked to the press and begun to reach the front pages, with stories appearing in the New York Times and the Washington Post. The State Department made a brief announcement about the possibility of a “low yield nuclear explosion” which was currently under investigation, and sent out guidance to embassies. That same day, Smith briefed the House Foreign Affairs Committee, whose members were miffed that they had not been told earlier, as the intelligence committees had been; that, Smith told them, was a White House decision. In response to speculation whether Israel or South Africa had staged the test, Smith noted that “we had no evidence that South Africa was responsible” and “we had an equal amount of evidence that Israel was responsible, i.e., none.”

Document 16: Evening Reading Item for the President, “South African Statement on Reported Nuclear Event,” 27 October 1979, Confidential

A day after the leak, the State Department made a brief announcement, almost identical to the one Smith had recommended, that the possibility of a “low yield nuclear explosion” is currently under investigation, and sent out guidance to embassies. U.S. press coverage had associated the incident with South Africa, which led to a public denial from Foreign Minister Pik Botha that his government had any knowledge of a test. The following day, in what was probably a diversionary move, the South African Embassy relayed a statement to the State Department that the South African Navy was instructed to begin an investigation of the possibility that the alleged nuclear event monitored by the U.S. may have been caused by an accident aboard a Soviet (or other) nuclear submarine on station" in the South Atlantic. The item for the President noted that an “an accident aboard a submarine was one of the first possibilities that occurred to the intelligence community after the signal was received; it was concluded that the signal observed was not consistent with a reactor accident aboard a nuclear vessel.” Moreover, U.S. intelligence knew of no nuclear submarine that had been in the area.

Document 17: U.S. Embassy Pretoria telegram 09920 to State Department, “Suspected Nuclear Event: Still No Meeting with Prime Minister,” 31 October 1979, Secret

Acting on instructions from the State Department, U.S. Ambassador William Edmundson tried to see South African Prime Minister P.W. “Piet” Botha, to discuss the press stories and to ask him to reaffirm his predecessor’s statement to President Carter in October 1977 that his government had not developed or intended to develop a nuclear explosive device “for any purpose.” While vainly trying to arrange the meeting, Edmundson saw Foreign Ministry Secretary Bernardus “Brand” Fourie who told him about a report by South Africa’s Atomic Energy Board which stated that “daily samples of radioactivity have never been lower.” Fourie commented that “your people should know that there has been no explosion, that the whole idea is nonsense,” an observation to which Edmundson took exception.

This encounter was of a piece with Edmundson’s recent meeting with Foreign Minister Botha, who alternately ridiculed the report and blamed “it on some other country or cause.”

Document 18: U.S. Embassy Pretoria telegram 10020 to State Department, “Suspected Nuclear Event: Renewed Guidance Needed,” 5 November 1979, Confidential

Noting that the media coverage of the Vela event was fuller than the information provided to him by Washington, Edmundson wrote that he would not be able to tell the South African prime minister anything that he did not already know. Moreover, he implied that his instructions did not help him answer a question that he had already been asked informally by South African officials. Why did the USG not approach the South African government “in confidence,” immediately after the 22 September event? As Edmundson noted, that answer was fairly obvious – South Africa was a “prime suspect” – but the more diplomatic answer was that the information was from a sensitive system and Washington had to verify it first. What was more important was to try to get an “authoritative denial of nuclear explosive activity” from the prime minister and Edmundson suggested that the U.S begin with a written approach. The suggestion was apparently moot because the meeting never occurred.

IV. Briefing the Soviets

Document 19: U.S. Embassy Moscow telegram 24665 to State Department, “Reported Nuclear Explosion Off South Africa,” 26 October 1979, Confidential

In light of the 1977 consultations with Moscow about the Kalahari test site and “our common interest in heading off proliferation,” Ambassador Thomas Watson sent a tightly controlled “Nodis Cherokee” message meant for Secretary Vance and his close associates only. Recommending discussions with the Soviets about the Vela incident, Watson proposed that Washington provide as much information as possible to encourage Soviet reciprocity.

Document 20: U.S. Embassy Moscow telegram 24869 to State Department, “Suspected Nuclear Event,” 30 October 1979, Confidential

Having received authorization to brief the Soviets, the Moscow Embassy’s science counselor met with Ivan G. Morozov, deputy chairman of the State Committee for the Utilization of Atomic Energy. Believing that the Vela signal was “correct” and that “South Africa was the likely culprit,” he emphasized the importance of taking “very energetic measures not to let the situation develop further.” If it was established that “other countries in addition to South Africa” were involved “(presumably an indirect reference to press reports about possible Israeli involvement), this could very seriously undermine the non-proliferation treaty.” Morozov’s further observations were polemical, e.g., he was skeptical whether Washington really wanted to know what had happened or whether it had tried hard enough to use technical intelligence to find out.

Document 21: U.S. Embassy Moscow telegram 24941 to State Department, “Suspected Nuclear Event,” 31 October 1979, Confidential

A briefing for officials at the Foreign Ministry’s International Organizations department produced more straightforward discussion with no questioning whether the U.S. had tried hard enough to identify the Vela event. According to the Embassy’s commentary, “while making no promises, they projected a desire to be helpful if they can in determining what happened on September 22.”

Document 22: Dick Combs S/MS [Special Adviser to the Secretary] to Allen Locke, William G. Bowdler, and Leslie H. Brown, “Attached cable to Amb. Watson,” 31 October 1979, Confidential

In a follow-up message sent a few days later, Watson noted that he was surprised that Washington had not briefed Moscow “long before [the story] leaked to the press.” Vance instructed the Department to reply by noting that this does not represent a policy change, and that Washington had delayed because the “initial information was highly inconclusive” and that U.S. “allies were concerned that precipitate action might complicate other important issues” such as the ongoing talks over Rhodesia/Zimbabwe.

Document 23: U.S. Embassy New Delhi telegram 21883 to State Department, “Briefing Soviets Suspected Nuclear Event,” 30 November 1979, Secret

When visiting New Delhi for the IAEA’s General Conference, Gerard Smith found an opportunity to discuss the Vela incident with Ivan Morozov during a discussion of the controversy over whether South Africa should have credentials to participate. Morozov suggested that Washington had precipitated the controversy by announcing the Vela incident, a suggestion that Smith disputed. After Smith asked whether Moscow had any information that could shed light on the nature of the incident, Morozov said that “his bureau” (the State Committee on Nuclear Energy) did not, but, as Smith’s aide, Allen W. Locke, observed in the message, “he did not say that his government did not.” For further exchanges, such as at a forthcoming bilateral meeting on 5 December, Smith proposed talking points on what the United States did and did not know. The record of any discussions on 5 December 1979 has not yet surfaced.

V. False Alarm from New Zealand

Document 24: U.S. Embassy Wellington telegram 06051 to State Department, “Possible Evidence of Southern Hemisphere Nuclear Test,” 13 November 1979, Secret

In a “Nodis Cherokee” message, the U.S. Embassy in New Zealand reported that scientists at the Institute of Nuclear Sciences had discovered short-lived radionuclides in rainwater collected during the period between 1 August and 28 October. The source of the radioactive substances was unknown but it was very rare for such samples to appear in rainwater at that location, although the scientists had not ruled out the possibility of leakage from a recent French underground nuclear test. The scientists were trying to refine the time period during which the samples were collected and were looking into the possibility of sharing the rainwater with the U.S. government.

Document 25: U.S. Embassy Wellington telegram 06140 to State Department, “SITREP IV: Possible Evidence of Southern Hemisphere Nuclear Test,” 15 November 1979, Secret

A new report from the Embassy in Wellington described reservations about the rainwater samples (see previous document). According to the director of the Institute for Nuclear Scientists, Bernard J. O’Brien, further testing cast “considerable doubt” on the earlier results: they may have been “erroneous.” More tests would be made and the Institute was willing to share the rainwater with the United States.

Document 26: U.S. Embassy Wellington telegram 06157 to State Department, “SITREP V: Possible Evidence of Southern Hemisphere Nuclear Test,” 16 November 1979, Secret

While waiting to hear more from the Institute of Nuclear Sciences, the Embassy in Wellington sent a “Nodis Cherokee” message about another effort to identify “testable” sources of radioactive contamination: the thyroid glands of cows and sheep. Richard Batt, the chair of the Biochemistry/Biophysics Department at Massey University had been sending samples regularly to a professor at the University of Tennessee as part of a routine radiation monitoring program. Recent samples, including from Australia, taken during the relevant period showed “zero abnormal radioactivity.” Batt was “slightly contemptuous” of the Institute for Nuclear Sciences and believed that the University of Tennessee’s “track record of detecting nuclear explosion is excellent.”

Document 27: “Nite Note,” prepared at the Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs, 19 November 1979, Secret

A briefing paper prepared either for Secretary Vance or President Carter summarized the message from New Zealand concerning the “considerable doubts” about the rainwater. In addition, the University of Tennessee would receive its regular shipment of thyroid glands from sheep slaughtered in New Zealand – collected after the 22 September event. The university had also received a “similar shipment from Australia” but it revealed “no abnormal radioactivity.” Not documented in the Smith papers (or perhaps still classified) was that the next shipment taken in November showed the Australian sheep had ingested a fission product, iodine-131.

Also, according to the “Nite Note,” the panel organized by Frank Press – under the direction of Jack Ruina – to review the data would be “concluding its work in a few weeks.”

Document 28: U.S. Embassy Wellington telegram 06226 to State Department, “SITREP VI: Possible Evidence of Southern Hemisphere Nuclear Test,” 20 November 1979, Secret

A message from the U.S. Embassy in New Zealand provided an update with information from “other mission elements:” the “sum of available information appears to indicate that the initial report from the NZ Institute of Nuclear Sciences (INS) was a false alarm.” Supporting that conclusion was a visit to Zealand by Colonel Robert S. McBryde, chief of the Diagnostics Division of the Air Force Technical Applications Center (AFTAC), which was responsible for collecting data on nuclear activities around the world. McBryde’s technical report supported the conclusion about a “false alarm.” He raised questions about the technical procedures followed and noted the “low content” of Cesium 141 [CE] and the contamination of the original lanthanum [LA] sample. According to the report: “procedures, contamination in LA sample, and implied age of CE suggests to AFTAC rep that evidence of fresh fission products in INS sample is flimsy.”

Document 29: U.S. Embassy Wellington telegram 06276 to State Department, “SITREP VIII: Possible Evidence of Southern Hemisphere Nuclear Test,” 23 November 1979, Limited Official Use

The New Zealand rainwater affair came to an end through a public statement by INS director O’Brien that “new measurements … on the original rain water sample, and also on a larger 150-liter rain water sample do not confirm our earlier results.” “The original samples were contaminated with other radionuclides.”

VI. The Ruina Report and Its Implications

Document 30: Allen W. Locke to Thomas Pickering et al., “Secretary's Views on South African Nuclear Situation,” with report attached, 9 January 1980, Secret

In light of the completion of the Ruina panel report on the Vela incident, Arnold Raphel, Vance’s special assistant, had told Smith’s deputy Allen Locke that the secretary agreed with Smith that the report’s conclusions should be made public. Moreover, the report should be shared with allies to the extent possible. Implicitly, the report’s conclusion that a nuclear test was unlikely influenced Vance’s support for the resumption of nuclear negotiations with Pretoria. Vance, however, supported “some kind of UN sanctions if there is no progress with South Africa on the nuclear issue.”

Document 31: State Department telegram 009602 to U.S. Consulate Cape Town, “US Conclusions on South Atlantic Event and US-SAG Nuclear Dialogue,” 12 January 1980, Secret

Consistent with what Smith had recommended, Vance sent the U.S. Embassy in South Africa a double-barreled message containing: 1) the Ruina panel’s agnostic conclusions about the 22 September event, and 2) instructions to resume nuclear talks with South Africa. The panel’s basic conclusion was that it “was unable to determine whether the light signal recorded by the satellite was generated by a nuclear explosion or some other phenomenon.” Tacitly, Garwin had backed away from his “two-to-one” odds. After reviewing alternative natural phenomena which might have caused the flash, the panel ruled out all but one: “the possible reflection of sunlight from a small meteoroid or a piece of space debris passing near the satellite.” The full report was not completed until May 1980, but its basic finding was along the same lines: “the September 22 signal was probably not from a nuclear explosion.”

That the panelists saw no compelling evidence for a nuclear test took South Africa off the hook. Therefore, Vance informed the U.S. Embassy that “we have decided to make another attempt to reach a nuclear settlement with South Africa.” Washington had not ruled out sanctions against South Africa but any decision would depend on “Our judgment of the SAG's willingness to move promptly toward a satisfactory nuclear settlement.” That would depend on Pretoria’s accession to the Non-Proliferation Treaty, the negotiation of full-scope safeguards on its nuclear facilities, including the enrichment plant at Valindaba. Moreover, South Africa would have to accept a reduced level of enrichment of fuel for the Safari nuclear reactor to 20 percent.

Document 32: Frank Press to Henry Owen and Gerard Smith, “South Atlantic Event,” 17 January 1980, Secret

The same day that an article by Thomas O’Toole appeared in The Washington Post about the internal debate in the Carter administration about the Vela incident, Frank Press wrote to Owen and Smith – acknowledging that the Ruina panel he created was a response to their request – that he supported the search for more data on the Vela incident.[18] Recognizing that the White House panel could not confirm that a nuclear detonation had occurred, Press conceded that “we cannot exclude the possibility that this continuing data gathering and analysis may turn up some corroborative evidence in the future if a nuclear explosion had actually taken place.” As he noted, the panel urged the search for more data; Press strongly recommended that in discussions with other governments we “leave open the possibility for finding such corroborating evidence in the future.” It is worth noting that the provisional judgement of the Ruina panel notwithstanding, a few weeks later President Carter wrote in his diary that “We have a growing belief among our scientists that the Israelis did indeed conduct a nuclear test explosion in the ocean near the southern end of South Africa.”[19]

Document 33: Jerry Oplinger to Henry Owen, “South Atlantic Event,” 23 January 1980, Secret, excised copy

Source: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library, NLC 28-32-4-16-5

That the Intelligence Community objected to the first cut of the Ruina panel report is evident in this memo from Gerald Oplinger, a nonproliferation specialist on Brzezinski’s staff, to Ambassador-at-Large Henry D. Owen. According to Oplinger, the IC was dissatisfied with the treatment of key issues such as the Vela signals and an ionospheric disturbance, occurring at the time of the 22 September event, which scientists using the radio telescope at Arecibo Ionospheric Observatory (Puerto Rico) had detected. Oplinger noted that key officials, including John Deutch (under secretary of Energy and subsequently CIA director), Daniel Murphy (deputy under secretary of defense for policy), and John Marcum (on Press’s staff) recognized that the IC objections meant the necessity for a “fresh airing” of controversial issues to avoid continued internal dissent and a report that looked like a “whitewash for political reasons.” Yet Oplinger was critical of their thinking because he believed that they took a “c.y.a.” approach, with their “bottom line that there is no conclusive case for a nuclear source.”

Apparently, Murphy was going to make a presentation of the issues and Marcum believed that only a few people needed to hear it. Oplinger objected to that; he wanted Smith to be present along with Owen, Deutch, Press, and CIA officials. Whatever Oplinger may have thought about the Vela event, he wanted all the interested officials to hear the presentation before decisions would be made about Congressional consultations and press releases. What happened next remains unclear, but it was not until May 1980 that the Ruina panel completed its report.

Document 34: State Department telegram 29416 to U.S. Consulate Cape Town, “Guidance on Suspected Nuclear Event,” 2 February 1980, Secret

On 30 January 1980, the Washington Post ran a follow-up article, also by O’Toole, on the South Atlantic event, “New Light Cast on Sky-Flash Mystery,” which discussed a CIA report on a secret South African naval exercise at the time of the Vela incident. According to the State Department, O’Toole had garbled Defense Attaché Office (DAO) reports on two events: 1) a harbor defense exercise in Simonstown, and 2) a “report of an alert of air-sea search and rescue teams at Saldanha Bay.” Other than the reports on those events, the intelligence community reportedly had no information about other South African naval activities around 22 September.

The Department advised Embassy officers to inform South African officials that the O’Toole article reflected a “selective and highly distorted interpretation of data” on the Vela incident and that it did not “reflect executive branch positions” and drew in part upon unauthorized disclosures.

Document 35: U.S. Consulate Cape Town telegram 0239 to State Department, “Guidance on Suspected Nuclear Event,” 4 February 1980, Confidential

Against the background of deteriorating relations with South Africa, Ambassador William B. Edmondson wrote an exasperated reply to the Department’s guidance on the Washington Post article. It was “simply not good enough to be of any help to explain why the USG cannot prevent [the] recurrence of unauthorized disclosure[s]” that lead to a “highly distorted interpretation.” The leaks “run the risk of creating the impression that the USG (or elements thereof) is deliberately carrying out a propaganda campaign” against the South African Government.” Noting that the prime minister and the foreign minister “angrily resent the accusations and insinuations” about the South African connection to the Vela incident, Edmondson believed that it would “do more harm than good” to tell them the Washington Post article did not reflect official thinking. Edmondson cautioned the Department to “keep in mind the likely mood and attitude in these matters as it affects our efforts to reach a nuclear agreement with the SAG as well as our overall relations, including greater SAG suspicion and surveillance of mission reporting activities.”

Document 36: U.S. Embassy London telegram 02824 to State Department, “South Atlantic Event,” 7 February 1980, Confidential

Confirming the close information-sharing relationship with the British, but also illustrating the difficulties caused by information controls for inter-governmental communications, the U.S. Embassy in London asked the Department to follow up on two recent queries from Whitehall: 1) the relationship of an ionospheric ripple to the 22 September event, and 2) intelligence information on South African naval activities cited in the Department telegram on 2 February (above), which was also routed to London. On the latter point, the 2 February telegram was relevant, but because it was under “Nodis” controls it could not be shared with the British; the Embassy asked for a report that could be shared.

The point about the ionospheric ripple was a reference to a “traveling ionospheric disturbance,” occurring at the time of the 22 September event, which scientists using the radio telescope at Arecibo Ionospheric Observatory (Puerto Rico) had detected. The Embassy had public information on the ionospheric ripple, but sought more guidance from the State Department.

VII. Israeli Connections?

Documents 37A-B: The CBS Story on the Israeli-South African Nuclear Connection

Document A: Department of State Telegram 046986 to Multiple Embassies, “CBS Story on Israeli Nuclear Weapons,” 22 February 1980, Limited Official Use

Document B: U.S. Embassy Tel Aviv telegram 03811, “Israeli Reaction to CBS Story on Israeli Nuclear Test,” 26 February 1980, Confidential

On the evening of 21 February, “CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite” ran a major story on Israeli-South African nuclear cooperation based on the work of CBS radio stringer Dan Raviv. According to the story, Israel had produced “dozens” of atomic bombs and “several hydrogen bombs.” Raviv’s sources were two Israeli writers, Eli Teicher and Ami Dor-On, who had an unpublished manuscript, None Will Survive Us: The Story of the Israeli Atom Bomb, which Israeli censors would bar from publication. The authors and another high-level Israeli source (Eliyahu Speiser, an Israeli politician who served as a member of the Knesset for the Alignment between 1977 and 1988), told Raviv that the Vela event was an Israeli test “with the assistance and cooperation of South Africa.”[20]

Raviv filed the story in Rome to circumvent Israeli press censorship regulations, a move that Israeli authorities saw as a “crass and clear violation” of the rules. The Government Press Office (under instructions from Minister of Defense, Ezer Weizman), quickly revoked his press credentials. According to the Embassy report, the reaction of most Israelis had been “so what else is new,” but the CBS Bureau was “the most upset.” Apparently Raviv had not coordinated the report with the acting bureau chief, who asked CBS headquarters to “kill it.” For unspecified reasons the bureau chief saw the report as a “non-story.” Walter Cronkite covered it nevertheless, although Robert Pierpoint backtracked from the story a few days later.

Not surprisingly, the Embassy was skeptical of Raviv’s account: “while not in possession of all the scientific evidence, we believe it would be the height of folly for Israel to indulge in any form of nuclear weapons testing, in particular in conjunction with South Africa; and we believe all responsible Israeli officials share this appreciation.”

Document 38A-B: Jack Ruina’s Source

Document A: Department of State Telegram 050226 to U.S. Embassy Vienna, “September 22 Event,” 25 February 1980, Confidential

Document B: Department of State Telegram 0502090 to U.S. Embassy Vienna, “September 22 Event,” 27 February 1980, Confidential

Another thread involving a possible Israeli connection had far more limited circulation. While Gerard Smith was in Vienna on IAEA business, Allen Locke kept him in the loop on developments, including information that MIT Professor Jack Ruina had acquired from “personal contacts” relating to the “theory of Israeli involvement” in the 22 September event. Ruina considered that information “significant, but inappropriate for discussion on telephone.” Ruina had already given an account to his MIT colleague, George Rathjens, who had worked on Smith’s staff. In the follow-up telegram, Locke reported that Ruina had met with John Marcum, Frank Press’s executive secretary and that the unspecified information “appears to be quite speculative.”

As noted earlier, Ruina’s source was Israeli missile engineer Anselm Yaron, who was then a visiting fellow at MIT. There, with Ruina and other MIT personnel, Yaron had discussed Israeli defense programs, including Israel’s nuclear weapons capability. In the course of those discussions, Yaron said or implied that the Vela incident was an Israeli-South African test.[21]

VIII. Lingering Debates and Mysteries

Document 39: Robert A. Martin INR/PMA [Political-Military Affairs], to AF/S [Office of Southern African Affairs] Paul Hare, “Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) Analysis of Data Relevant to 22 September 1979 Possible Nuclear Event,” 17 June 1980, Secret

On 26 June 1990, the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) made what amounted to a rebuttal of the Ruina panel’s finding when it published its own interpretation of the 22 September event, The South Atlantic Mystery Flash: Nuclear or Not?. The contents of the DIA report remains classified (although under appeal at the Interagency Security Classification Appeals Panel), but some of the information it highlighted appeared in an INR memorandum of a discussion with Jack Varona, who was then the agency’s assistant vice director for scientific and technical intelligence. Speaking with Robert A. Martin, the director of INR’s politico-military bureau, Varona argued that the Ruina panel was a “white wash, due to political considerations” and that it had used “flimsy evidence” to arrive at a “non-nuclear” explanation. Varona argued that the “weight of the evidence pointed towards a nuclear event.” In particular, he believed that hydroacoustic data, which had only recently been analyzed by the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) and was not fully available to the Ruina panel, involved “signals ‘which were unique to nuclear shots in a maritime environment.’” The source of the signals was the area of “shallow waters between Prince Edward and Marion Islands, south of South Africa.” Varona also explained why the attempts to collect radioactive debris had come to naught: “radioactive waste would not necessarily have been detected from a low-yield, near-surface nuclear explosion in a maritime environment south of the African continent.”

Document 40: Matthew Nimetz through Warren Christopher to the Secretary, “South African Nuclear Problem,” 8 September 1980, with memorandum from Warren Christopher attached: “South African Nuclear Problem,” 27 September 1980

Source: Smith Files, box 20, South Africa 1980

Lingering ambiguities of the 22 September event are exemplified by this action memo from September 1980, prepared by Allen Locke for Under Secretary for Security Assistance, Science, and Technology Matthew Nimitz, which includes a useful overview of the South African nuclear program (see “Annex”). The memo proposed three options or modalities for nuclear negotiations with South Africa, with the central issues being whether and how to go through the French. It also touched upon the Vela event, noting the “conflicting conclusions of the Press [Ruina] Panel and the DIA, which have received public attention” as underlining an American “dilemma”: how far Washington could go in trying to negotiate with South Africa without increasing African suspicions that it was trying to cover up South Africa’s nuclear development “with a treaty.” In the report’s annex, the author argued that it was “prudent to assume that South Africa has the uranium and design experience required to manufacture nuclear explosives on short notice.” Locke then noted that it was “widely assumed” that a South African nuclear test was the explanation for the 22 September “event,” notwithstanding the lack of “direct evidence to support this, nor even agreement on whether the ‘event’ was a nuclear explosion.”

Document 41: Intelligence Coordination to Zbigniew Brzezinski, “Evening Report,” 1 December 1980, Secret

Source: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library, NLC 10-33-4-4-6

The DIA’s Jack Varona had argued that a nuclear test might not have produced radioactive fallout, but the testing of thyroid glands in Australian sheep mentioned in Document 27 suggested an alternative possibility. According to this memo from Brzezinski’s intelligence staff, the thyroid glands of sheep slaughtered near Melbourne during October 1979 showed “abnormally high levels” of Iodine 131, a “short-lived isotope that occurs as the result of a nuclear event.” The sheep had grazed in an area where it had rained during 26-27 September 1979. DIA would be investigating whether the Iodine 131 could have been ingested as a result of nearby industrial or pharmaceutical activities. Why it took so long for the test results to reach DIA was not explained.

Notes

[1]. Jimmy Carter, White House Diary (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010) p. 357.

[2]. Leonard Weiss e-mail to Avner Cohen, 19 September 2016.

[3]. Jimmy Carter, White House Diary, p. 405.

[4]. See Leonard Weiss’s “Israel’s 1979 Nuclear Test and the U.S. Cover-up,” Middle East Policy,” Vol. 18 No.4 (2011); “The 1979 South Atlantic Flash: The Case for an Israeli Nuclear Test,” in H. Sokolski, ed., Moving Beyond Pretense: Nuclear Power and Nonproliferation (Harrisburg, PA: Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College Press, 2014), 345-371; and “Flash from the Past: Why an Apparent Israeli Nuclear Test in 1979 Matters Today,” The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, (8 September 2015). “Flash from the Past: Why an Apparent Israeli Nuclear Test in 1979 Matters Today.” See also Timothy McDonnell, “International Conference: The Historical Dimensions of South Africa's Nuclear Weapons Program,”4 January 2013, Nuclear Proliferation International History Project.

[5]. Avner Cohen, The Worst-Kept Secret: Israel’s Bargain with the Bomb (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010), 81-84.

[6]. The Vanunu revelations refer to information on the Israeli nuclear program published in the London Sunday Times on 5 October 1986 based on the testimony of Mordechai Vanunu, a former Israeli nuclear technician at the Negev Nuclear Research (Dimona). From the Vanunu revelations it became apparent that Israel was a more advanced nuclear weapons state than had been estimated. Qualitatively, it appeared that Israel had mastered the means and know how to manufacture advanced nuclear weapons, i.e., boosted weapons and possibly full two- stage (thermonuclear) weapons. Quantitatively, the size of the Israeli nuclear arsenal, based on the production of plutonium, was estimated at about 100-200 weapons, much larger than had been projected. Vanunu was subsequently captured by the Mossad, brought back to Israel, and sentenced to 18 years in jail. Vanunu was released from prison in 2004, but remains this day is subject to a broad array of restrictions on his speech and movement. Full text of the Vanunu disclosure. For a detailed analysis of the Vanunu disclosure see, Frank Barnaby, The Invisible Bomb (London: I. B. Taurus, 1989). See also Avner Cohen, The Worst-Kept Secret: Israel’s Bargain with the Bomb (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010), 131-35.

[7]. For details, see Sasha Polakow-Suransky, The Unspoken Alliance: Israel’s Secret Relationship with Apartheid South Africa (New York: Pantheon Books, 2010).

[8]. “Israel Reported Behind A-Blast Off S. Africa,” The Washington Post, 22 February 1980.

[9]. Richelson, Spying on the Bomb, 313.

[10]. Seymour Hersh, The Samson Option: Israel’s Nuclear Arsenal and American Foreign Policy (New York: Random House, 1991), 281-282. Anselm Yaron (1918-2003) was one of the pioneers of Israeli rocketry, starting in the 1950s as a rocket engineer in RAFAEL (Weapons Development Authority). In the 1970s he directed the Israeli program to develop satellite launchers. On the prominent role of Yaron in Israel’s defense R&D systems, see the autobiography of Brigadier-General Uzi Eilam, Eilam's Arc: How Israel Became a Military Technology Powerhouse (Sussex: Sussex Academic Press, 2011). (Eilam was the chief of the Israeli Defense Force’s R&D branch and later, during 1976-1985, the director-general of the Israeli Atomic Energy Commission.) Yaron arrived at MIT around 1980, shortly before he retired. The ACDA-funded project on which he was one of the team members produced a study, submitted in June 1981, “Assessing the comparability of dual-use technologies for ballistic missile development.” The other authors of that study were Ruina, Mark Balaschak, and Gerald M. Steinberg.

[11]. Rod Nordland, “The Bombs in the Basement,” Newsweek, 11 July 1988, 42.

[12]. For the items in the FRUS volume, on Israeli-South African nuclear cooperation, see Documents 291, 292, 300, 303, and 304 at pages 901-904. 920-921, and 923-926. Other telegrams on this topic remain classified and have been requested from the State Department.

[13]. Avner Cohen, The Worst-Kept Secret (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010), 32.

[14]. The substance of the report corroborates Jeffrey Richelson’s account in Spying on the Bomb, 296-297.

[15]. Richelson, Spying on the Bomb, 298.