Washington D.C., November 19, 2019 – One hundred years after the birth of Anatoly Dobrynin, one of the most effective ambassadors of the 20th century, the former dean of the Washington diplomatic corps is being remembered in both his home country and the United States for his abilities, not least in helping to manage the ever-turbulent relationship between the two superpowers for almost a generation during a pivotal period of the Cold War.

Dobrynin was universally respected for his many skills but even more for his desire to serve as a straightforward, non-ideological mediator and negotiator between the two rival powers, the United States and the USSR. His role in confidential back-channel communications with senior American officials from Robert F. Kennedy during the Cuban missile crisis to Henry Kissinger in the era of détente helped build a basic level of confidence and trust on both sides that was crucial to resolving or averting numerous actual and potential crises.

While he developed an unusual personal connection with the United States, where he lived from 1962, the year of the Cuban episode, to 1986, mid-way through the Reagan administration, he not surprisingly considered himself an unabashed loyalist to the Soviet Union.

“I served my country to the best of my ability as citizen, patriot, and diplomat. I tried to serve what I saw as its practical and historic interests and not any abstract philosophical notion of communism. I accepted the Soviet system with its flaws and successes as a historic step in the long history of my country, in whose great destiny I still believe. If I had any grand purpose in life, it was the integration of my country into the family of nations as a respected and equal partner.”

As noted below, after his retirement he continued to contribute to international understanding through his memoir, which has become something of a manual of diplomatic craftsmanship, and especially through his cooperation with the global scholarly community including participating in a number of conferences and projects organized the National Security Archive over several years.

The following documents and excerpts from three of those conferences from the mid-1990s (see "New documents" below) show Dobrynin “in action” – both as an active diplomat engaging American officials in confidential interactions and after his retirement, providing his former U.S. counterparts and scholars what at the time was almost unprecedented direct perspective from the Soviet leadership whose inner workings and decision-making were still largely opaque so soon after the collapse of the USSR.

Documents

Document 01

At the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis, in late October 1962, Dobrynin negotiated the secret compromise on withdrawing U.S. “Jupiter” missiles from Turkey with Attorney General Robert Kennedy, which allowed Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev to save face in front of his own Presidium and remove the Soviets’ intermediate-range missiles from Cuba. Dobrynin remained involved, negotiating daily with members of the Kennedy administration until the crisis was fully resolved -- thanks to a large extent to his professionalism, persistence and the trust that developed between him and his American partners.

Document 02

In the late 1960s, having established himself as a knowledgeable, efficient -- and famously affable -- diplomat, Dobrynin developed a close relationship with National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, which resulted in a unique, secret communications link between the U.S. and Soviet leadership -- the “back channel.” During most of the Nixon administration, all important issues of the superpower relationship were discussed and often resolved within the framework of “The Channel.”

This conversation covers the entire spectrum of U.S.-Soviet relations, effectively establishing an informal agenda for President Nixon and General Secretary Brezhnev. A top priority of the new American administration would be resolution of the Vietnam conflict, on which Nixon sought Soviet help. Other focal points included an early meeting with the Soviet leadership, arms control and non-proliferation, the Middle East, and European security.

Compared to Kissinger’s version, Dobrynin’s notes of the conversation are much more detailed and precise, as was usually the case

Document 03

In this telephone conversation with Dobrynin during the final stages of the negotiations on the Vietnam war in Paris, and only days before the White House decision to renew heavy bombing of North Vietnam, President Nixon discusses his desire to remove the issue of North Vietnam as an “irritant” in U.S.-Soviet relations. The snippet offers a revealing glimpse of Dobrynin’s personal approach to dealing with U.S. presidents. While maintaining an almost cheerful informality with an evidently uncomfortable Nixon, the Soviet envoy shows his capacity for precise detail, even managing to correct the president on a small factual point.

Document 04

Dobrynin’s relationship with Kissinger quickly became a comfortable one and it evolved into a personal friendship, as is evident in their telephone conversations, which are full of jokes and mutual teasing. However, this closeness was also crucial to helping both men deal with international crises such as the October 1973 war in the Middle East. On a lighter note, the two officials broach a subject that comes up often during their conversations in the back channel. Dobrynin notes that Kissinger has been seen with an attractive young woman previously pictured in a Playboy calendar. Kissinger calls Dobrynin a "dirty old man" and expresses his "hope she isn't a nice girl."

Document 05

Ambassador Dobrynin and Henry Kissinger trade more banter as the ambassador offers to sing "Happy Birthday" to Kissinger a day before the latter travels to New York. Kissinger then asks for a favor: “Now Anatol do you mind not letting KGB guys run[] loose in the streets of Washington where I see them at night[?]” Asked if he too had been “running around the streets” the night before, Kissinger answers, “If you must know, I just brought a girl home.” They then turn to a discussion of logistics for Brezhnev’s upcoming U.S. visit and details of various arms control proposals.

Document 06

Dobrynin congratulates Kissinger on his nomination to the position of Secretary of State and passes on high praise from Leonid Brezhnev and Andrei Gromyko. When told that the Kremlin had made a decision in connection with the news, Kissinger speculates whether it was to appoint him a member of the Politburo. Dobrynin laughs and says: “Almost … You probably know all our secrets,” then adds: “Secondly, they would like you to get a permanent visa to go to Moscow and just to call you ‘Excellency’ when you come.” Kissinger later calls Dobrynin "not just a colleague, but a personal friend."

Document 07

After sharp remarks from President Nixon at a news conference on the Arab-Israeli crisis, Alexander Haig telephones Dobrynin to reassure him the president did not intend to ratchet up the crisis. Dobrynin launches into an emotional response describing the difficult position Nixon’s comments have created for the Politburo “domestically” (and by implication for Dobrynin himself who has to explain U.S. actions to his superiors). He says the Kremlin is particularly upset about the president’s comparison of the situation with the Cuban missile crisis (which the translator erroneously records as the “human crisis”), and resents the implication that as a result of U.S. actions the Soviets were made to look like "weaker partners … against [the] braver United States." But after a few moments, the Soviet envoy calms down and repeatedly thanks Haig and the president for their concern to “keep the personal relationship as strong as it was before.”

Document 08

In the mid-1970s, Dobrynin was also the main conduit between the U.S. and Soviet leadership on the Conference for European Security and Cooperation (CSCE), including the very sensitive Basket III provisions of the Helsinki Final Act. In this conversation, Dobrynin and Kissinger talk briefly about the Conference and the progress of SALT negotiations. Kissinger asks Dobrynin to "cooperate a little bit on Basket III," which encompassed human rights and individual freedom of movement. Dobrynin emphasizes the importance of the Conference to the Soviet Union, and the confidential nature of the exchanges on this subject, saying that "Gromyko … will keep this close to his heart. It is a project that he likes very much."

As usual, the conversation is sprinkled with humor. After Dobrynin assures Kissinger that he has been wrongly informed that Dobrynin is about to become foreign minister, Kissinger laments: “Well, we’ll have to take that wiretap off the Kremlin then.” To which Dobrynin responds: “ … [O]r you have to fire those who are making them … and get a better one.” The two go on to compare the difficulties of working for one man (the president) versus a Politburo of 15, including one unnamed member, as Kissinger cracks, “who thinks he is an expert.”

Document 09

Even though the back channel did not function under the Carter or Reagan administrations, Ambassador Dobrynin continued to provide a trustworthy direct link to the Soviet leadership. Dobrynin found himself in a difficult situation having to negotiate on arms control while responding to the Carter administration’s unwelcome pressure on human rights violations in the Soviet Union, as he would later to the Reagan administration’s arms buildup. In this conversation with former Ambassador to the USSR Averell Harriman, who had served as a conduit to Moscow for Democratic Presidents since World War II, Dobrynin is informed that President-elect Carter intends to move quickly to finalize and conclude an agreement on the limitation of strategic weapons with Leonid Brezhnev and sign a treaty at an early summit with the Soviet leader.

Document 10

Ambassador Dobrynin receives instructions from Moscow to meet with Secretary of State Cyrus Vance and deliver a rebuttal to recently inaugurated President Carter’s human rights initiatives and specifically his support for Soviet dissidents, which Moscow sees as an example of interference in Soviet internal affairs. Dutifully, Dobrynin subsequently tried to explain to Vance how the public human rights campaign was perceived in the Soviet Union and how he believed it could interfere with progress in arms control negotiations.

Document 11

In this conversation on the eve of Vance’s departure for Moscow to present a U.S. proposal for “deep cuts” of strategic forces to the Soviet leadership, Dobrynin warns the Secretary of State that this idea would be unacceptable to the Brezhnev Politburo on the grounds that it is deeply asymmetrical and represents an abandonment of an earlier agreement that Brezhnev was prepared to sign. His warning proves to be prescient, and Vance’s visit marks the beginning of a major downturn in U.S.-Soviet relations.

Document 12 - NEW

Freedom of Information Act request to State Department

In this State Department memorandum, Dobrynin provides the secretary of state with a "tour d'horizon" with particular attention to the Middle East. This document is typical in the sense of showing Dobrynin offering candid insights into Soviet leadership thinking and reactions. Here, he explains why the Soviets "reacted so strongly to the Sadat initiative -- because "they had just succeeded in obtaining Syrian agreement to go to a Geneva conference when Sadat announced his trip to Jerusalem."

Document 13 - NEW

TsKhSD, Fond 89, Opis 76, Delo 28, pp. 1-9

Here, the Soviet ambassador provides Foreign Minister Gromyko with some insights into the explanatory value of seeing the ties between American foreign and domestic policy. He reports that Carter's national security advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski, and certain domestic aides have persuaded Carter that he can halt his political decline by adopting a "more hard line course with regard to the Soviet Union. As a pretext one selected Africa (the events on the Horn of Africa, and then in the Zairian province of Shaba)."

Document 14

This extraordinary memo from KGB chief Yurii Andropov and Leonid Brezhnev represents a back channel of a different kind -- an end run around the Politburo to persuade the Soviet leader of the need to send troops to Afghanistan. The decrepit Brezhnev by this time had ceded virtually full control of foreign affairs to the troika of Andropov, Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko and Defense Minister Dmitrii Ustinov. After reading Andropov’s “alarming information” about “a possible political shift to the West” by Afghan leader Hafizullah Amin, Brezhnev consents and within days the entire Soviet leadership has signed off on the invasion.

Dobrynin gained access to the Russian Presidential Archive and was permitted to take notes of the document, which he then presented to an international conference in Norway in 1994. Without his personal involvement, this and many other critical pieces of historical information might never have entered the public domain.

Document 15

In this memorandum, Dobrynin, as head of the International Department of the Central Committee, advises Gorbachev on his next moves toward the United States. Dobrynin explains perceptively the dynamics of the presidential campaign in the U.S. and suggests that Gorbachev should try to meet with President-elect George H.W. Bush as early as possible, before he is inaugurated, in order to preserve continuity and momentum in U.S.-Soviet relations. The best time and location for such a meeting, Dobrynin advises, would be in New York, especially if Gorbachev is to deliver an address to the U.N. General Assembly. As predicted, the address provides a major stimulus for a new start in U.S.-Soviet relations.

Document 16

In this memorable intervention during a “critical oral history” session on U.S.-Soviet relations during the Carter-Brezhnev period, ex-Ambassador Dobrynin explains the secrecy and compartmentalization of Soviet decision making in foreign policy. Among other undesirable effects, it results in Soviet diplomats being forced to learn the terminology for Soviet weapons systems from the American negotiators.

Original posting

Washington, D.C., April 14, 2010 - Anatoly Fedorovich Dobrynin--the former Soviet Ambassador to the United States who served under five Soviet leaders and six U.S. Presidents, and was a long-time academic partner of the National Security Archive, died on April 6, 2010, in Moscow.

Mr. Dobrynin became Soviet envoy to Washington in the critical year 1962. Virtually from the start, he found himself in the thick of the most important developments of the Cold War, playing a key role at major turning points like the Cuban Missile Crisis, which flared later that year and became the first crucible of his long diplomatic career. During the decades that followed, Dobrynin became the interlocutor on U.S.-Soviet relations for presidents, secretaries of state, and national security advisers.

After Mikhail Gorbachev emerged as Soviet leader in 1985, Dobrynin gave his full support to the new reform program (perestroika). In recognition of his expertise, he was appointed head of the influential International Department of the Central Committee and became a valued adviser to Gorbachev, with actively involvement in developing new policies toward the United States, toward the socialist bloc, ending the war in Afghanistan, and drafting the foreign policy sections of the report to the landmark XIX Soviet Communist Party Conference in 1988.

Anatoly Dobrynin was an invaluable participant in several projects of the National Security Archive. Even before the end of the Cold War, he showed a genuine interest in helping to uncover and explain that extraordinary period of history to the world public, going well beyond the usual authorship of memoirs.

As an early participant in a ground-breaking series of “critical oral history” conferences (organized primarily by professors James G. Blight and janet M. Lang) on the Cuban Missile Crisis (starting in 1988), followed by a project (in the mid-1990s) on the collapse of détente during the Carter-Brezhnev period, he was unrivaled in his generosity and willingness to be questioned for hours by scholars and to engage in keen discussions with his former American adversaries, including Robert McNamara, Arthur Schlesinger, Cyrus Vance and Zbigniew Brzezinski.

His near-photographic memory for policy minutiae and his crackling wit gave a riveting sense of the atmospherics of his time and made it plain how he managed to gain the confidence and respect of so many during his tenure in Washington.

Substantively, his contributions to each of these multi-session academic conferences, full of deep insight and unforgettable anecdotes, substantially advanced our knowledge of the Cold War. His personal warmth and empathy toward Cold War partners and opponents alike will remain in the memories of those who were lucky enough to come to know him.

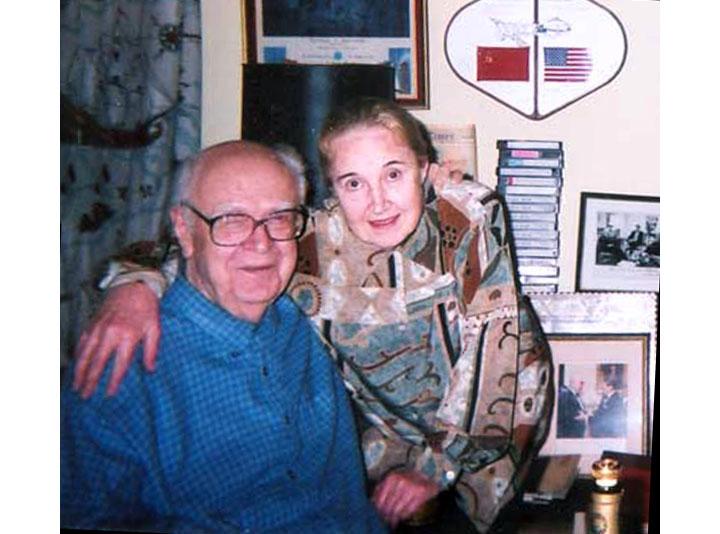

The National Security Archive mourns the passing of our friend and partner, Anatoly Fedorovich Dobrynin, and celebrates his life and achievements. We express our condolences and our heartfelt appreciation to his wife and closest partner of 68 years, Irina Nikolaevna.