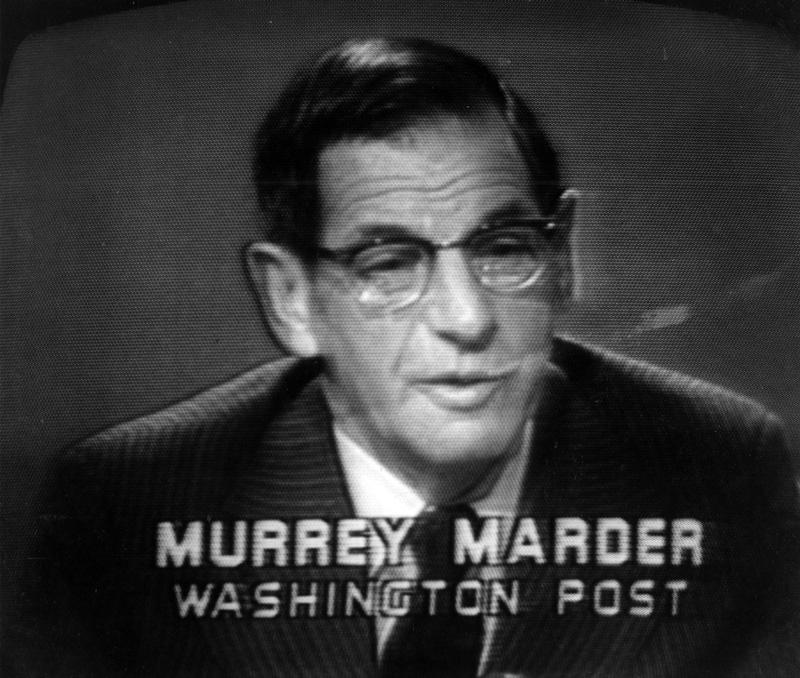

Washington D.C., July 20, 2017 – During a frank conversation with Washington Post reporter Murrey Marder in early 1967, Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey said that “he is no longer sure he was right” when he initially supported decisions to bomb North Vietnam in 1965. The bombing of North Vietnam had “poisoned the atmosphere” by alienating people who would otherwise be supportive of the Vietnam War and by substantiating North Vietnamese propaganda.

Later in the conversation, the record of which is published today for the first time by the National Security Archive, Humphrey “attacked” President Lyndon Johnson “for the first time in [Marder’s] private talks with him since he became Veep.” He criticized Johnson’s handling of the Manila summit with East Asian/Pacific leaders by “telling everyone that nothing would be accomplished.” After Johnson returned, he “failed to campaign” during the 1966 mid-term elections. “The press unloaded on him and thought up all the other times that Johnson had buffaloed them.” Humphrey warned that “Johnson could lose in ’68. If things go wrong … the Republicans could take it.”

Publicly, Humphrey was a dutiful and enthusiastic supporter of Johnson’s Vietnam policy and his internal dissent did not become known for years. Murrey Marder kept Humphrey’s confidences and those of other government officials. During the course of a long career with the Washington Post, as an aid to memory while writing stories, Marder prepared detailed records of his conversations with U.S. government officials and foreign leaders, including prime ministers, secretaries of state and defense, and national security advisers, ranging from Harold Macmillan, Dean Rusk, and Henry Kissinger to Robert McNamara and Roswell Gilpatric. The collection, which Marder donated to the National Security Archive after his death in 2013, includes his records of conversation and many by his Washington Post colleagues, including Chalmers Roberts, Philip Geyelin, David Broder, and Robert Eastabrook.

To highlight the interest and research value of these documents, the Archive is publishing a selection of them. Other records of Marder’s backgrounders published today include:

- A discussion with an unnamed secret source (“007”) on 2 March 1965, the day the “Rolling Thunder” bombing of North Vietnam began, which according to the source, was “a major step” that “is expected to go on until there is some change of heart by Hanoi and/or Peking.” According to the source, although Hanoi was aligned with Moscow, the Soviets did not see Southeast Asia as a “major concern,” thus, the odds that the bombing raids would trigger a nuclear war were low, “9 to 1” against.

- A conversation with an unidentified State Department source, soon after the revelations of CIA support for the National Student Association, about CIA-State Department relationships. Press stories about “covert support to Christian Democratic parties” could be “extremely explosive if they blow, but so far they haven't, although German and Italian press are starting to sniff at the edges of this.”

- A conversation about Vietnam in May 1967 with Assistant Secretary of State William Bundy, who acknowledged that where “we erred in the decision to escalate was that we did not foresee the extent of combat involvement … and possibly most people thought bombing would change Hanoi's mind faster.”

Today the Archive is pleased to announce that the Murrey Marder collection is open for use to interested researchers. It includes over 700 memoranda and notes of Marder’s off-the-record conversations and background briefings by senior U.S. government officials from the late 1950s into the early 1980s. Many of these documents are too fragile to be handled directly by researchers. To solve this problem, the Archive has scanned all of these memoranda so that visiting researchers can review images of the originals. They will be available for use on a computer at the Archive’s reading room.

Life and Times of Murrey Marder

Murrey Marder worked as a journalist at the Washington Post for 39 years (1946 – 1985). He was born in Philadelphia on 8 August 1919, where his father had a grocery business. Marder began his career in journalism after high school graduation in 1936, at age 17, when he started work as a “copy boy” at the Philadelphia Evening Ledger. After four years, he became a cub reporter at age 21.[1] On the eve of America’s entry into World War II, Marder enlisted in the U.S. Marines, and eventually became a combat correspondent in the South Pacific. He participated in four combat operations in the Solomon Islands and on the island of Guam. After two years, he transferred to Washington, D.C. to manage the Marine Corps news desk.[2]

After the war, Marder joined the city staff at the Washington Post in 1946, later moving to the national staff. He soon distinguished himself on what he called “the Red Beat,” the Alger Hiss case in 1949, and Senator Joseph McCarthy’s allegations of communist infiltration of government and various industries. In the autumn of 1953, McCarthy held closed-door hearings that resulted in the suspension without pay and loss of security clearances of 42 employees at the Army Signal Corps Laboratory at Fort. Monmouth, New Jersey because of alleged Commuist “espionage.” Marder spent a week at Ft. Monmouth and was able to prove that the charges had no merit.[3] After his articles on the matter appeared in the Post, the Secretary of the Army, Robert Stevens, admitted at a news conference that the charges were false, and that the Army had known this.[4]

Marder’s reporting won him a Fellowship at the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University from 1949 -1950. At Harvard, he concentrated on studying foreign affairs, including diplomatic, economic and Soviet and Chinese affairs.[5] These interests are reflected in his papers inventoried here, but no papers have been found in this donation on his coverage of the McCarthy era.

Even before the Nieman Fellowhip, Marder had begun covering foreign affairs in 1948 when he was assigned to the U.S. State Department. In 1957 he opened the paper’s first foreign bureau in London, serving there from 1957-1960. As the Post’s chief diplomatic correspondent, from the Eisenhower administration to the Carter administration, Marder traveled with secretaries of state, and sometimes presidents, to international conferences and summit meetings all over the world.[6]

Marder covered diplomatic developments relating to the escalation of the Vietnam War. He viewed his coverage of Vietnam as his greatest failure because he felt that if the press and Congress had been doing their jobs, America would never have gone to war. The allegations that North Vietnamese torpedo boats had carried out an unprovoked attack on two U.S. destroyers raised doubts in his mind. From his military service Marder knew that torpedo boats are not equipped to attack destroyers. Despite his efforts to uncover the truth about the incident, the Washington Post editorial page, along with other major newspapers, endorsed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution that granted President Lyndon Johnson authority to assist any Southeast Asian nation considered jeopardized by “communist aggression,” and served as a justification for escalating the war in Vietnam.[7]

When the fuller story of the Vietnam decision-making process in the Pentagon Papers became available to the Washington Post and the New York Times, publisher Katherine Graham included Marder in discussions with top editors about whether the Post should publish the papers. In her memoir, Graham quotes Marder as saying, “If the Post doesn’t publish, it will be in a much worse shape as an institution than if it does” because the paper’s “credibility would be destroyed journalistically for being gutless.”[8] When the Post began publishing the Pentagon Papers, Marder was assigned to write stories based on the documents.

Marder’s colleagues described him as “quiet, intelligent, dogged and meticulous.”[9] Above all, he was careful and fair. This earned him the trust of many American and foreign officials which is reflected in the off-the-record interviews they granted to him. During the Johnson administration in 1965, Marder popularized the term “credibility gap,” which was used to describe the gulf between the White House’s version of the Vietnam war, and the reality the reporters on the ground there reported.[10]

Ben Bradlee, the former executive editor of the Washington Post, paid Marder a back-handed compliment when he described his as “one of the world’s most thorough reporters.”[11] He apparently drove editors mad by writing and re-writing articles right up to deadline to make sure he got the story as accurate as possible. This is seen in his papers where there are multi-page copy sheets, with anywhere from one to 12 addenda (known in the trade as “take one, “take two,” etc.)

One of the most valuable parts of the collection for researchers is the series of background interviews that Marder and fellow “Posties” conducted with American and foreign officials. They called them “backgrounders.” The internal Washington Post memoranda and notes, and the journalists’ memos to each other found in the Correspondence series illustrate how reporters shared information gleaned from these interviews and other contacts. They can be read together with the memoranda of the background interviews.

From 1977 to 1978 Marder was a Whitney Shepardson Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations where he managed a project on American-Soviet perceptions in foreign policy with support from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.[12]

Marder retired from the Post in 1985. After his wife’s death in 1996, he donated his Washington Post stock, then worth about 1.3 million dollars, to the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University to set up the Watchdog Project.[13] Bill Kovach, 1989 Nieman Fellow, called Marder a “pathfinder,” and his friend, longtime Post reporter Morton Mintz, called him a “steady and wise watchdog.”[14] He died on March 11, 2013 at the age of 93.

SELECTIONS FROM THE MARDER DONATION

The following materials reflect the scope of the collection, covering issues across the Cold War landscape – from the Vietnam War to nuclear weapons to domestic wiretapping to U.S. foreign relations.

Document 1:Background Only Wednesday Dec. 2, 1959 [Interview of Harold Macmillan by 15 U.S. Journalists]

Interviewed after the recent Conservative election victory in Britain, a “self-satisfied” Prime Minister Macmillan reviewed domestic and international issues. On the horizon was an East-West summit involving the Western “Big Three” (Eisenhower, Macmillan, and de Gaulle) and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev to discuss the Berlin problem, among other issues, but more imminent was a Western summit to discuss preparations for the meeting with Khrushchev. Macmillan reviewed trade issues, NATO, British-German relations, French-German relations, and the Russians.

Some years before the United Kingdom began trying to join the European Common Market, Macmillan tried to advance British commercial interests through “self-protection”: the creation of a free trade area with the “Outer Seven” (Norway, Sweden, Denmark, etc.). Seeing West Germany as Britain’s major commercial rival, Macmillan was uneasy about the “militaristic tendencies latent in the Germans.”

Document 2: “Apr. 25, 1962. Talk with Dep Secy. Defense Roswell Gilpatrick [sic], with Roberts and Marder”

After briefly reviewing the nuclear testing situation and U.S. disarmament proposals with Marder and his colleague, Chalmers Roberts, Deputy Secretary of Defense Gilpatric turned to U.S. nuclear policy in NATO Europe. The Kennedy administration had been considering whether to provide France with assistance for its nuclear program, but would not do so because it was determined “to pull nuclears out of Europe, rather than put more in.” Under consideration, Gilpatric said, was the prospect of a deal with the Russians to pull nuclear weapons from “ground units” in Europe and by 1963-1964 to withdraw IRBMs (Intermediate Range Ballistic Missiles) from Italy and Turkey.

Days later, the Post would publish reports that President Kennedy was ordering cuts in the production of nuclear weapons, but that he had approved the deployment of Davy Crockett nuclear mortars for U.S. forces in NATO Europe, which would complicate any talks with Moscow over nuclear deployments in Europe.[15] The prospect of withdrawing nuclear weapons from Western Europe would come to naught and in the years that followed, Washington would deploy thousands of them in West Germany and elsewhere on the continent.

Document 3: “Secretary Rusk November 22, 1962 Deep Background”

A few weeks after the most dangerous phases of the Cuban Missile Crisis had passed, Secretary of State Dean Rusk met with unidentified Washington Post and possibly other reporters for a background briefing. The briefing focused on Cuba, including the status of the IL-28 bombers in the negotiations,[16] but also on the Sino-Soviet split, which Rusk saw as “real,” and the recent Sino-Indian conflict. On Cuba, Rusk discussed the public Kennedy-Khrushchev correspondence, which he observed was a “reflection of the urgency of the situation. Communications simply could not take place through private channels, at the rate events were moving.” [17] While he claimed that one of the letters, Khrushchev’s 26 October missive, would not be made public for “25 years,” events were moving more rapidly than he knew because it had been published in the Department of State Bulletin only a few days earlier.

Rusk kept the most important secret—one that never appeared in a Kennedy-Khrushchev letter—that President Kennedy’s agreement to remove U.S. Jupiter missiles from Turkey and Italy was part of the settlement. A reporter’s question referred to the Jupiters, but Rusk avoided answering that part of the question.

Document 4: “Background Lunch with McGeorge Bundy on 7th Floor, Mr. [Alfred] Friendly in chair July 13, 1964”

A private luncheon with national security adviser Bundy began with a discussion of Cuba, Laos, Cyprus, UN peacekeeping, and the 1964 election. Showing the impact of domestic politics on White House decisions, Bundy argued that it would be “insane” to have talks with Castro during the campaign. Much of the discussion was on the Multilateral Force (MLF), a proposal for a multilaterally-controlled NATO nuclear force, Marder saw Bundy’s MLF presentation as “dutifully arguing” the case for it but “hedging his bets on the outcome.” According to Bundy, the “fundamental issue” in the MLF was “wrapping in Germans to head off any independent German nuclears.”

Concerned that West Germany might feel impelled to develop a nuclear capability if its nuclear status was not upgraded somehow, U.S. policymakers saw the MLF as a way to give the Germans a nuclear role (“safety valve”) without their fingers on the nuclear trigger. While the U.S. would have a veto over the use of the MLF’s weapons, one of the reporters noted that State Department official Robert Bowie had argued that the MLF’s “logical conclusion” was the “withdrawal of the American veto,” a point from which Bundy “strongly dissented.” Yet as Marder noted, President Johnson and other officials had implied the same thing.[18]

Document 5: “Luncheon Today Background Only with Source OO7 (name blacked out) March 2, 1965”

From a source so secret that Marder blacked out the name, he learned about the initiation of the Rolling Thunder bombing campaign against North Vietnam: “Today's raid on N. Vietnam is a major step, ending the retaliation phase and entering the phase which is expected ·to go on until there is some change of heart by Hanoi and/or Peking.” President Johnson was determined to escalate “until Hanoi cracks in some form,” but no one could be sure “when or how that might come.” Also, according to the source, although Hanoi was aligned with Moscow, the Soviets did not see Southeast Asia as a “major concern,” thus, the odds that the bombing raids would trigger a nuclear war were low, “9 to 1” against.

Marder and Chalmers Roberts covered the bombings in several stories in early March, with Roberts making clear the policy change: “The President has embarked on a course of using military power to force the communist regime in Hanoi to do an about face.” That anyone in government had even considered a nuclear risk was secret, although Marder noted that it “never moved into a foreseeable state of high international tension as it is doing now.”[19]

Document 6: “Memo on conversation with Humphrey, Executive Office Building, January 4, 1967”

Here, the vice president offered a candid discussion of the Vietnam war, military strategy, and the political prospects for 1968. Convinced that the administration’s bombing policy was “locked in” by public opinion, “hawks” in the Senate, and the Air Force, Humphrey believed the “best thing now is perhaps quiet diplomacy, try to put together a package in secret that can be sold to the American people. He is waiting it out for the 1968 election. He thinks perhaps Johnson' s policy will be repudiated and the war can end that way.” In the meantime, he favored de-escalation in “tiny stages.”

Document 7: Feb. 21, 1967 “’CIA Complex’ Marder Lunch with State Official, Ass’t Secy Level Ruminations Guidance Only”

Ramparts magazine had just published a ground-breaking exposé of the CIA’s years of secret financial aid to the National Student Association and more covert funding links were becoming exposed. A few days into the scandal, a State Department official more or less candidly discussed the Department’s dealings with the Agency, jokingly referring to a “Church-State” area of the relationship as if suggesting that the separation was less than strict. The source commented on disputes over whether it was CIA or the State Department that motivated covert operations and the lack of critical scrutiny within the government over CIA activities. Another danger was that the CIA was tainting the “liberal, anti-Communist left,” which had received important funding overseas.

The source observed that German and Italian journalists were trying to learn about CIA funding for their Christian Democratic parties and further noted that the CIA had a strategy of getting “critical entrée into the top layers of national life.” At first glance, this may be taken to mean that supporting political parties was important for longer-run CIA access to decision-makers in a foreign society, but the source had a larger point to make: that CIA was trying to recruit the “cream of [U.S.] intellectuals,” apparently to give it more support in American society.

Document 8: “Interview with McNamara April 28, 1967 4:45-5:30 p.m.”

It is not clear who at the Post interviewed Robert McNamara and wrote it up, but the distribution list at the top of the first page may include the author’s name, whether Marder or Ben Bradlee or someone else. Whoever wrote it had given McNamara a document (not attached to the original) indicating some charges that had been made against him: the sub-headings on the memorandum may have corresponded to the topics, for example: Resignation, Distress about Effort to Stifle Dissent, His Influence on Decisions, Urging Senators to Speak Out Their Dissent on War, Bombing Haiphong, and Bombing Dikes.

Refusing to spill details of White House deliberations, McNamara made it evident that he was critical of recent decisions to bomb surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites in North Vietnam because of the high costs of such attacks, including the downing of pilots and aircraft. His doubts did not come to light in the Post for nearly a month, when the paper published an article on Johnson’s Vietnam advisers: McNamara had “challenged the bombings on what might be described a cost-effectiveness basis.” Moreover, according to the Post, “Despite accusations that McNamara is a cold, computerized man, he has deep feelings and agonizes over the loss of pilots.”[20] That dovetails with this account: when asked how he felt about U.S. casualties, McNamara “for a fleeting instant lost his composure.”

Document 9: “Ben Read (head of executive secretariat, who functions as a sort of mac bundy for the secy. of state) May 4, 1967”

Read is highlighted in the title, but this conversation included William Bundy, who was then serving as assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs. The discussion focused on the role of the “Tuesday lunch” in President Johnson’s decision-making, with characterizations of key figures, including McNamara and Rusk. National security adviser Walt Rostow had influence over Johnson, according to Bundy, in part because he “puts the President's programs in grand historic perspective, makes them sound like major developments in the sweep of history, as part of a consistent, logical, and intellectual pattern. All Presidents like this.”

The conversation revealed more doubts about Vietnam, with Bundy observing that where “we erred in the decision to escalate was that we did not foresee the extent of combat involvement … and possibly most people thought bombing would change Hanoi's mind faster.” Bundy further observed that “Who will ever know whether Johnson would have [escalated] if he had known how far he would have to go.” He was “sure” that “Kennedy would have gone down substantially the same road. Saigon was about to go under, had to do something.”

Bundy discussed the Polish-Italian peace initiative, code-named “Marigold” in Washington, which had developed during the last half of 1966.[21] He “insisted that only military action that may have crossed diplomatic line without realization that was happening was Dec. 1-2 bombing of Hanoi.” Bundy “implied they were surprised by it because it cut across bows of Warsaw probe operation.” As for the next bombing operation, the 13 December bombing of the Hanoi area, that was a “planned decision … despite Warsaw probing operation.”

Document 10: “Marshall GREEN, Office talk. August 28, 1969”

In this conversation, Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Marshall Green gave a defense of William P. Rogers, whom Nixon had appointed secretary of state, who had no background in foreign relations, to serve as a “front man” for White House decisions.[22] After praising Rogers for his skills as an interlocutor, Green acknowledged that he “does lack the background” and that “Nixon” is making foreign policy.” It was perfectly acceptable, however, for the State Department to operate as a “service organization” for the White House; “what’s wrong with that?”

Document 11: “Henry A. Kissinger - Jan. 23, 1970 - Off Record dinner with Washington Nieman Fellows.”

During this wide-ranging discussion, Kissinger reviewed the Vietnam War negotiations, China policy, Sino-Soviet tensions, and Nixon’s personal style, among other issues. On Vietnam, he stated that “negotiations will succeed to the extent that we can pose to Hanoi an alternative that is worse than negotiations.” Kissinger later explained that the “worse alternative” was for Hanoi to have to negotiate with Saigon, although he might have meant, in the back of his own mind, escalation and a massive bombing and mining campaign. During some of the conversation, Kissinger dissembled; for example, he claimed that “there are few super-secret things that are worth knowing,” as if keeping secrets was not a huge preoccupation of the Nixon administration.

When one of the reporters asked “Why is Nixon so remote from us?” Kissinger replied that “I never think of him as a remote president. The very factors that make him remote from you make him close to his staff.” Then later, Kissinger he confirmed that in fact Nixon was rather remote: “This president operates alone. He withdraws (in preparation) when he has to go public … He doesn't feel the need for a lot of people to talk to.”

Document 12: “Henry Kissinger – Dec. 19, 1972, phone call with Marder”

The day after the beginning of Operation Linebacker II, the “Christmas bombings” of North Vietnam, national security adviser Henry Kissinger called Marder to “blow his top” about a Washington Post article reporting that he had tried to make 126 changes in the peace agreement. Kissinger was also mad that a Post editorial had “impugned his motives and his ‘good will.’”[23] He closed the conversation by alluding to the White House ban on contacts with the Post: “You know I’m not supposed to talk with you.”

A more detailed version of this conversation can be found in the transcripts of Henry Kissinger’s telephone conversations. Kissinger had a staffer listening in while Marder appears to have done his from memory or on the basis of rough notes. The White House transcriber did not catch one of the names mention in the conversation, the famous Washington Post editor, Philip Geyelin, who had turned the editorial page against the war in Vietnam.

Document 13: “Marder Interview with Henry Kissinger Re Wiretapping, May 14, 1973”

In 1969, when New York Times reporter William Beecher discovered, through journalistic techniques, the secret bombing of Cambodia and published an article about it, he enraged Nixon, who was sure that someone, possibly on the White House staff or at the Pentagon, had leaked the story. Suspicion quickly fell on NSC staffer Morton Halperin, who had worked at the Pentagon during the previous administration and had known Kissinger for years. Kissinger’s military assistant, then-Colonel Alexander Haig, made a formal request to the FBI for wiretapping authority, but the wiretap targeted others, including Helmut Sonnenfeldt, on Kissinger’s staff, and General Robert Pursley, who was a military assistant to Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird.

In the spring of 1973, the wiretap secret went public and Kissinger was on the hook. As Marder’s record of conversation demonstrates, Kissinger was determined to avoid acknowledging responsibility for “initiating” the wiretaps and claimed that he had “discharged no one” because of them. That is strictly true, but during the summer of 1969 Kissinger did little to stop Halperin’s increasing marginalization on the NSC staff, which led his old friend and colleague to resign in frustration. Years later, long after Halperin had initiated a lawsuit over the wiretaps, Kissinger settled by apologizing: he accepted "moral responsibility" because he had "acquiesced in the tap."[24]

NOTES

[1]. Murrey Marder Obituary, The Telegraph, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/10085215/Murrey-Marder.html, accessed November 29, 2014.

[2]. Murrey Marder Profile, http://www.niemanwatchdog.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=about.viewadvisers&bioid=23, accessed on November 30, 2014.

[3]. Murrey Marder Obituary, The Boston Globe, http://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/2013/03/15/murrey-marder-longtime-post-reporter-who-covered-mccarthy-dies/UeXkf9I1XLZxDLLq15ga4K/story.html, accessed October 1, 2014.

[4]. Murrey Marder Obituary, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/20/us/murrey-marder-reporter-who-took-on-joe-mccarthy-dies-at-93.html?_1=0&pagewanted+print, accessed Nov. 30, 2014.

[5]. Murrey Marder Oral History Interview with Ted Gittinger, May 25, 1982. The transcript can be requested from the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library URL:

www.lbjlibrary.net/collections/oral-histories/oral-history-collection.html.

[6]. See Marder biographical notes, 1977, found in Series 23. He reported on all summit conferences since 1960 except presidential visits to China and Vladivostok in 1972 and 1974.

[7]. Ibid Telgraph obituary, note 1.

[8]. Graham, Katharine, Personal History. New York: Knopf, 1997, 449.

[9]. Halberstram, David, The Powers that Be. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2000, 194-199, 529, 572.

[10]. Ibid note 2.

[11]. Ibid The Boston Globe [tk: right name?] obituary, note 3.

[12]. Ibid note 6.

[13]. Ibid note 3. URL: www.niemanwatchdog.org.

[14]. http://niemanreports.org/articles/murrey-marder-pathfinder/. Accessed on 1 December 2014.

[15]. “President Planning to Order Cuts In Production of Atomic Weapons: Large Stockpile; Increase in Budget At Division Level,” Washington Post, 5 May 1962.

[16]. For the final phases of the Cuban crisis, see David G. Coleman, The Fourteenth Day: JFK and the Aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: W.W. Norton, 2014).

[17]. Rusk cited several letters: Khrushchev’s letters of 26 and 27 October; President Kennedy’s reply of 27; Khrushchev’s letter of 28 October; and Kennedy’s reply that same day.

[18]. Some days after this conversation, Marder wrote a lengthy piece about the MLF, “Politics Can Buffet Nuclear Fleet: Target Date for Multilateral Force Puts Maneuvering Between Europe And U.S. in Thick of Campaign,” Washington Post, 19 July 1964, which was informed by some of Bundy’s comments.

[19]. Chalmers Roberts, “Move by Other Side Awaited in LBJ’s Pressure on Hanoi,” Murrey Marder, “U.S. Appears Near Step-Up in Pressure on North Vietnam,” and Marder, “Façade of Calm Hides Pressure on Viet Reds,” Washington Post, 4, 11, and 13 March 1966.

[20]. “The Men Who Help LBJ Make Vietnam Policy,” Washington Post, 21 May 1967; no author attributed.

[21]. For a superb account of Marigold, see James G. Hershberg, Marigold: The lost Chance for Peace in Vietnam (Stanford University Press/Cold War International History Project Series, Palo Alto, 2012).

(Stanford University Press/Cold War International History Project Series, Palo Alto, 2012).

[22]. Raymond L. Garthoff, Détente and Confrontation: American-Soviet Relations from Nixon to Reagan, Revised Edition (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1994), 78.

[23]. What story Kissinger had in mind is unclear; an article by Marder in the Washington Post on 19 December 1972, “DMZ Status Stalls Talks, Say N. Viets,” did not mention 126 changes, neither did the editorial, ‘The Great Peace Charade,” that fed Kissinger’s ire.

[24]. William Beecher, “Raids in Cambodia by U.S. Unprotested,” New York Times, 9 May 1969; “Kissinger Issues Wiretap Apology,” New York Times, 13 November 1992.