Washington, D.C., November 14, 2017 – The National Security Archive mourns the passing of our most senior fellow, Dr. Jeffrey T. Richelson, prolific Freedom of Information Act requester and critically-praised author of extraordinary reference works on intelligence, nuclear weapons, China, terrorism, military uses of space, and espionage.

Dr. Richelson passed away on Saturday, November 11, 2017, at his home in Los Angeles after a months-long battle against cancer, according to his brother, Charles. He was 67.

Jeff Richelson ranks among the founders of the National Security Archive vision – that systematic Freedom of Information Act requests could force the government to open files that otherwise would remain secret indefinitely, and once open, these files could enrich scholarship and journalism and the public debate on issues like nuclear weapons and spying that very much needed public attention and skepticism.

As a member of the early 1980s informal SI-TK-Byeman group in Washington D.C., Jeff contributed documents and variable declassifications to the dynamic that led first Raymond Bonner of The New York Times, and then, most importantly, Scott Armstrong (of the Washington Post) to create the National Security Archive in 1985 as an institutional memory and permanent pressure group for open government.

As a Senior Fellow of the Archive since the 1990s, Jeff was the founding director of the Cyber Vault project, supported by the Hewlett Foundation, to publish the primary sources of cyber security policy, many of them previously classified and only opened as the result of his FOIA requests. The Cyber Vault remains a permanent tribute to the Richelson legacy.

Dr. Richelson authored an extraordinary series of essential reference books published by trade and academic presses. His volume on The U.S. Intelligence Community (Westview Press) entered its 7th edition in 2016, with encomiums ranging from Bob Woodward (“the authoritative bible on the modern American intelligence establishment”) to Professor Loch Johnson (“no one has ferreted out the details of this subject better than Dr. Richelson”).

The Richelson volume Spying on the Bomb (Norton 2006) gained particular attention with its analysis of the failures (and successes) of U.S. and international attempts to assess Saddam Hussein’s nuclear programs. Vitally, with a long view back to the Nazi nuclear program and forward to that in North Korea, the book cautioned both experts and public about the limits of knowledge along with the necessity of constant monitoring and skepticism about what we know and why we think we know it.

Dr. Richelson also wrote remarkable histories of the U.S. plans for responding to WMD attacks (Defusing Armageddon, 2009), the CIA’s science and technology directorate that created the U-2 and the Corona satellite (Wizards of Langley, 2001), the KGB (Sword and Shield, 1986), U.S. reconnaissance and early warning systems, and the long view of espionage (A Century of Spies, 1995), among 13 or so other volumes.

Frequent and patient FOIA requester, Dr. Richelson never counseled confrontation with the bureaucracy and never engaged in litigation, sometimes to a fault. His technique was that of obsessive mining of the public record, especially the defense and intelligence contractor trade press, arcane military bibliographies, and the Congressional hearing record, leading to targeted FOIA and declassification requests, accompanied by academic (not “gotcha”) interviews and participation in industry conferences. The net result was the liberation of tens of thousands of classified records that without his efforts would still be hidden in the vaults today. An additional result was that he would rarely if ever get credit for open government achievements that would have been impossible without him.

Much to his delight and also dismay, the signal moment when Jeff Richelson enjoyed Andy Warhol’s predicted 15 minutes of fame occurred in August 2013 when his research intersected with the international obsession with UFOs and Hollywood’s favorite secret space, Area 51. Jeff’s FOIA request forced declassification of the CIA’s internal history of Area 51, describing how senior officials chose the actual desert space in Nevada and then used it to test stolen Soviet MiGs as well as top-secret U.S. stealth aircraft. The NBC Today Show put Jeff’s visage into the breakfast rooms of millions of Americans as The George Washington University domain, which at the time hosted the Archive’s web site, experienced one of its biggest user spikes ever.

Dr. Richelson was also the researcher who forced the government to acknowledge the Acoustic Kitty project, in which the CIA surgically wired cats as surveillance tools, aimed at Soviet diplomats in Lafayette Square in Washington D.C., only to have a taxi splat the first test cat. A medical success, Richelson concluded, but an operational disaster.

Jeff also obtained through FOIA the first public acknowledgement (declassified in 2005) – later confirmed in spades by the Snowden leaks – that the National Security Agency was systematically intercepting the 4th Amendment-protected communications of Americans as it scooped up foreigners’ phone calls and Internet messages after 2001.

A competitive tennis player, passionate softball first baseman, and profound New York Yankees fan – Jeff also contributed significantly to the Archive’s embrace of telecommuting and distance learning, as he beamed in from Los Angeles to oversee the management of his extensive, pristinely organized files, and to direct, comment, and critique not only the development of the Cyber Vault but every Archive publication on nuclear weapons or the intelligence agencies, and more.

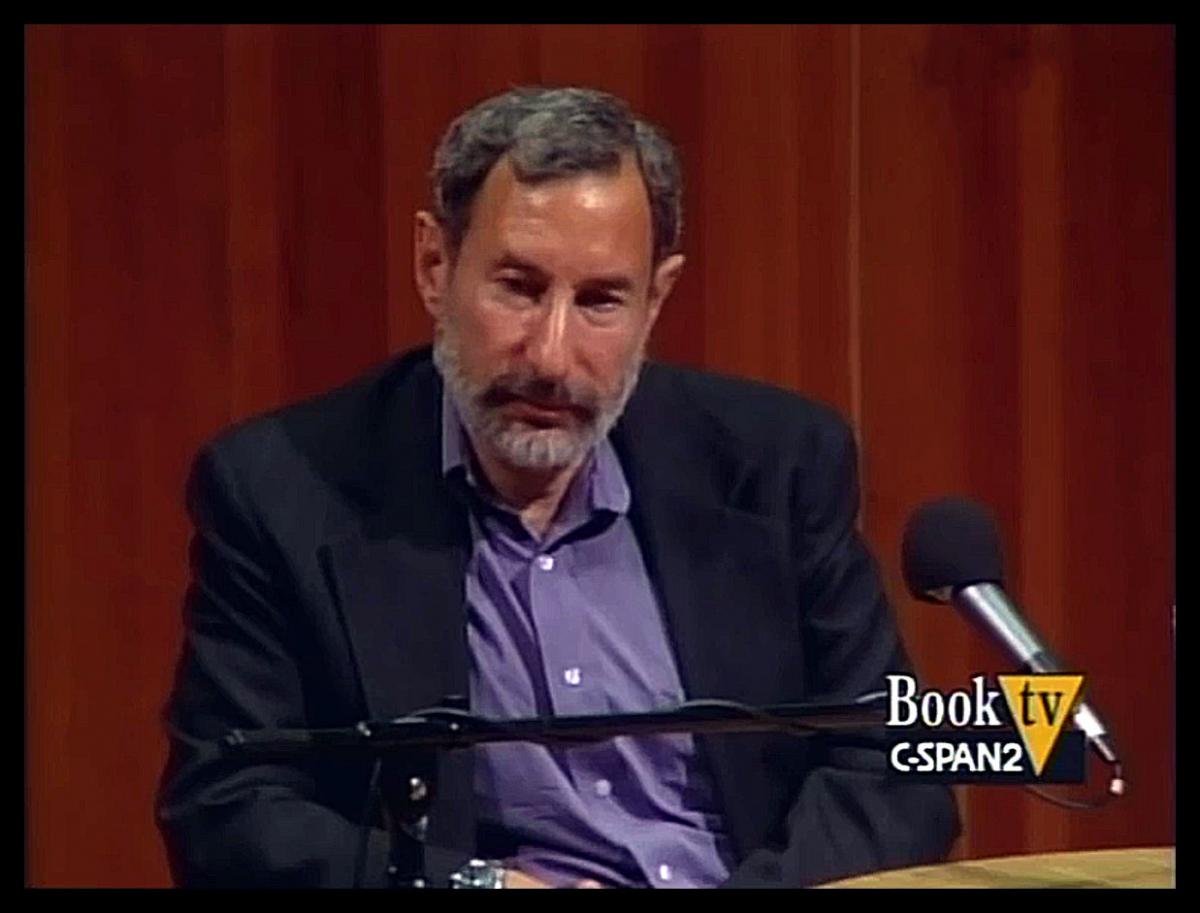

Jeffrey Talbot Richelson grew up in the Bronx, earned his B.A. at City University of New York and his Ph.D. at the University of Rochester. He later taught at the University of Texas at Austin, the American University, and Catholic University in Washington D.C. before joining the Archive full-time. He appeared on a variety of TV and radio programs, as well as on C-SPAN, and was regularly quoted in print media around the world.

Jeff never sought the spotlight but his work lives on, not just in his marvelously useful books but in the cornucopia of sources he made possible for generations of students and experts to come.