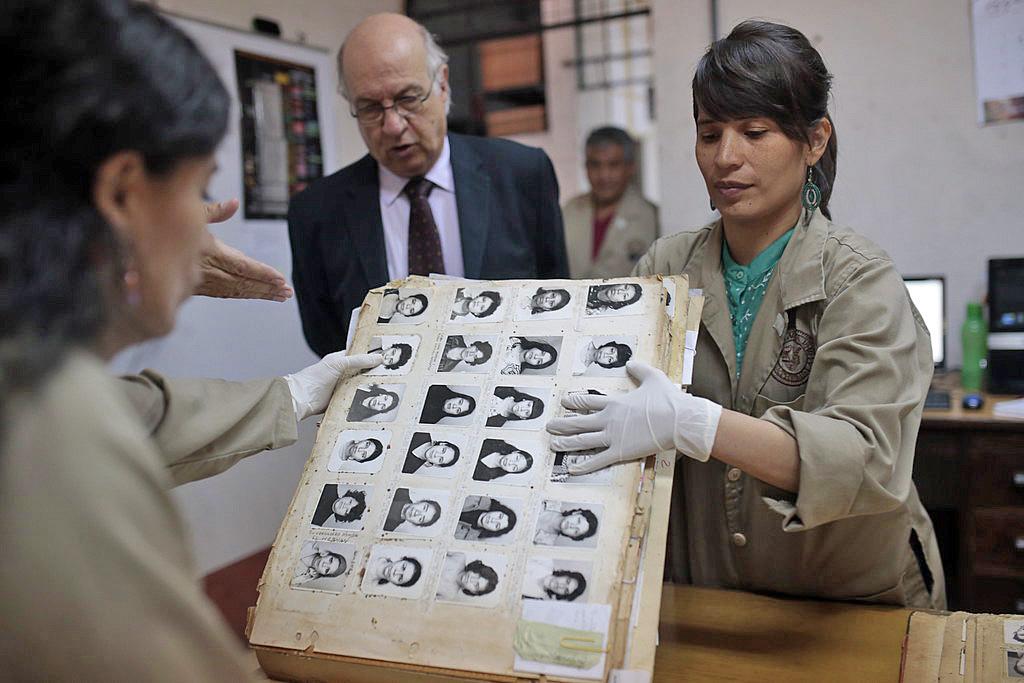

AHPN staff show a visitor a document from their holdings.

"Visita a Guatemala" by Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Washington, D.C., November 18, 2019 – The Historical Archive of the National Police of Guatemala (AHPN) is in trouble. This unparalleled collection of Guatemalan police records, renowned throughout the hemisphere and across the world, limps along in a drastically reduced state.

A staff that once numbered in the hundreds has dwindled to 35 people, operating on temporary contracts that need to be renewed every couple of months. Guatemala’s government pledged to continue funding the AHPN but refused to accept international assistance, so the Archive’s operating budget has been pared to a minimum. The investigations unit – which, in the past, constantly reviewed records for information to give to families of the disappeared, human rights investigators, scholars, and prosecutors – is gone. And according to two independent scholars who visited the Archive over the summer, outside researchers have not been permitted to conduct their work on the premises but are asked to submit record requests under Guatemala’s access to information law.

The news is not all bad. In some instances, the government has been forced to respond to sharply negative public reaction. Last May, Guatemala’s then-Minister of Interior, Enrique Degenhart, held a jarring press conference in which he announced his intention to reassert control over the Police Archive. Following public outcry and a crucial legal injunction filed by the Human Rights Prosecutor’s office, the government decided to extend the agreement granting the Ministry of Culture oversight of the AHPN for five more years (until 1 December 2024).

In April, the Ministry of Culture hired a civil servant named David Marroquín (formerly chief archivist at the National Registry of Persons, or RENAP) to head the AHPN. Since then, Marroquín has issued a thorough and professional internal report with recommendations about improving the preservation of AHPN records, standardizing archival procedures, and upgrading the physical space.

Notably missing from the report – and from the government’s vision for the Police Archive overall – is any reference to its profound contribution to historical memory about state violence and justice for human rights crimes in Guatemala.

Also deeply troubling is the government’s decision to smear, isolate, and criminalize two people who were central to the creation of the Historical Archive of the National Police and its flourishing: Gustavo Meoño, former Coordinator of the AHPN who was abruptly removed in August 2018, and Anna Carla Ericastilla, director for more than a decade of Guatemala’s national archives (Archivo General de Centro América, or AGCA) until her dismissal in July of this year. Ericastilla and Meoño are being accused by the government of “abuse of authority” for having entered into cooperative agreements with partner institutions such as the University of Texas, Austin, among other alleged misdeeds.

Meoño has left Guatemala and is now living outside the country. Ericastilla will give a declaration in her first hearing before the Public Ministry today, November 18, 2019, to address the criminal complaint filed against her.

The events transpiring within the Historical Archive of the National Police are the symptoms of something less dramatic than its outright closure. Rather, the AHPN appears to be in a state of suspended animation—its human rights and justice role eliminated, its former directors under criminal threat.

For these reasons, the International and National Advisory Councils of the AHPN – named by the Human Rights Prosecutor in 2007 and formally empowered by the Ministry of Culture three years later – decided to circulate a declaration of concern about the Police Archive’s current situation and the campaign against Anna Carla Ericastilla and Gustavo Meoño. A version of this declaration in English may be found below.