Fire Expert Refuted Government Claim That

Washington, DC, January 28, 2022 – National Security Archive continues the "After Ayotzinapa" project by publishing today the José Torero Cullen interview.

“After Ayotzinapa” is the result of a two-year collaboration between the National Security Archive and Reveal News from the Center for Investigative Reporting. Reported and co-produced by National Security Archive senior analyst Kate Doyle and Reveal senior reporter Anayansi Diaz-Cortes, the three-part serial reveals the story of what happened in the months and years following the forced disappearance of 43 college students in the state of Guerrero, Mexico on September 26, 2014. Part One: The Missing 43, aired on January 15. It describes the actual attack on the students. Part Two: Cover-Up, aired on January 22. It details the botched initial investigation and exposure of government obstruction. Part Three: All Souls, airing on January 29, addresses the efforts being made by a new government to overcome the cover-up and truly advance the cause of truth and justice for the missing 43 students. There are three ways to listen: on your podcast app of choice: Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher; on Reveal’s website, and on radio stations around the United States.

José Torero Cullen is a fire safety engineer and head of the Department of Civil, Environmental and Geomatic Engineering at University College London. He has contributed analysis to many high-profile cases of massive fire damage, including the collapse of the World Trade Center buildings, the 2005 Windsor Tower fire in Madrid, and London’s Grenfell Tower fire in 2017. Torero is interviewed in Episode 2 of the podcast After Ayotzinapa about his experience working with the group of international experts (GIEI) on the case of the 43 disappeared students.

Like most of the world, José first heard about the Ayotzinapa case through media reports. Once the Mexican government announced its findings as the “historical truth” (la verdad histórica) about what happened to the students, José’s expertise made him uniquely situated to evaluate a central aspect of the government’s story: the fire in the Cocula waste dump that allegedly incinerated the corpses of all 43 young men in a single night.

At the GIEI’s request, José flew to Mexico in July 2015 from where he was then teaching, at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia. José’s core finding - that a fire of the magnitude proposed by the government investigation could not have happened - ignited a scandal in the Mexican media. News organizations questioned his brief visit to the dump itself, and tried to discredit his conclusions without examining the analysis that led to them.

Anayansi Diaz-Cortes and I interviewed José Torero for the podcast on May 18, 2021. Below are extended excerpts from our conversation, in which José tells us about his experience working in the Cocula garbage dump and explains the science behind what he found there.

–Kate Doyle

The interview

José arrived in Mexico City from Australia, where right away he was confronted by “a level of stress and tension among all the people involved” that he had never faced before.

I was brought immediately to see some evidence by the lawyers, to meet the Argentinian forensic team who had photographs and information of all the work that they had been doing for a long period of time. And the next morning, we go directly to La Procuraduría General de la República (PGR–Mexico’s justice department) and we get put in a helicopter. It's such an unusual context for somebody like me who basically works on technical matters. We arrive in Guerrero, we jump into armored cars, people are carrying weapons, and you're being driven into this dump.

I'm an academic. My regular day is: I go to work, I interact with students, I teach classes, I do my research. I do the occasional investigation that forces me to go to the field. But taking a car to a senior government office, going to the roof, catching a helicopter, flying in a helicopter and then landing in a soccer field surrounded by military cars and people with automatic weapons, and being literally escorted into a car... I mean, that's more James Bond film than the type of environment in which someone like me is used to working.

We asked José: Can you describe the dump and what you found there that contributed to your conclusions?

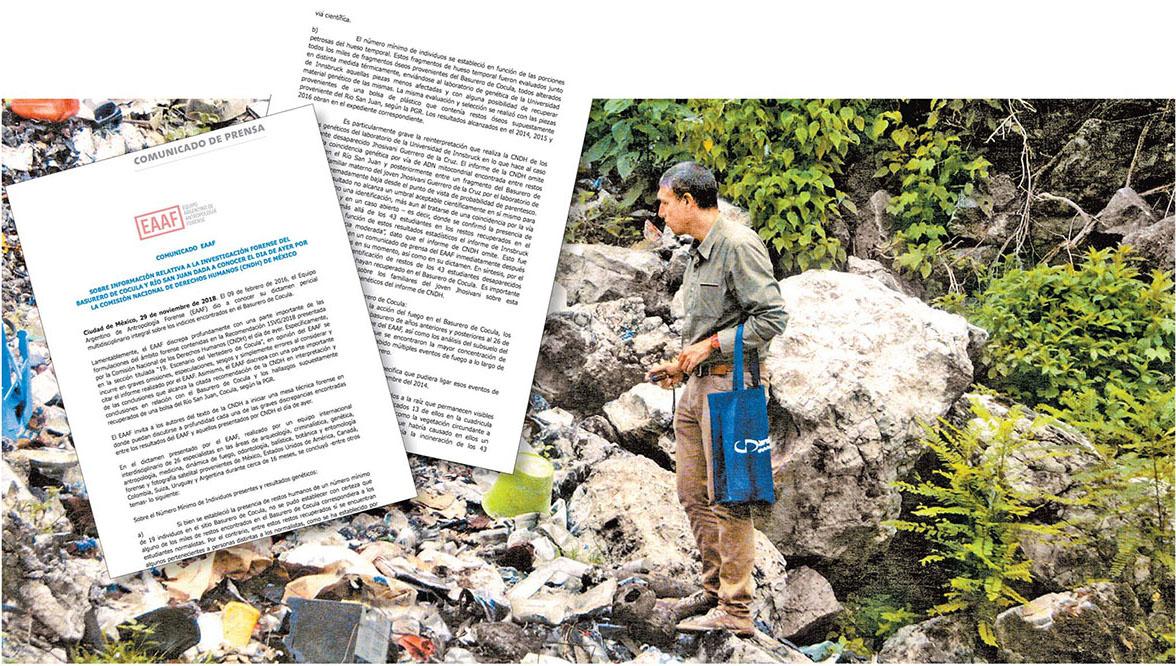

You have to descend maybe 150, 200 yards down into this hole, and the path that you're descending is incredibly steep, but also it’s not a path of soil, it is a path of garbage. So you have enormous amounts of garbage, plastic bottles, bags, you name it - insects all over the place, your legs are being eaten alive - and you have to walk through this garbage until you get to the bottom. [...] The whole bottom part of the dump had already been cleared, it had already been studied, a number of people had already collected a massive amount of evidence. [But] that's not really what I went to see.

If you're thinking about incinerating a very large number of bodies, what you're going to be needing is a very large fire. Now, a very large fire radiates an enormous amount of heat. And that enormous amount of heat, for example, when in proximity of plastic bottles will melt those plastic bottles and shrivel them and most likely actually ignite them. So you would have had significant evidence of fire-spread on the slope. So the slope would have been filled with burnt material. [...] What I did was a mapping of radiation. And I basically showed that as you moved away from the place where the fire was meant to be, you would have expected ignition of this garbage. You would have expected charring of the trees. You would have expected melting. So in principle, that slope would have had massive amounts of damage.

Now, instead, if you correlate the images that were taken days after the apparent incineration of these bodies, you will see that the same bottles - I managed to identify the same bottles that were in images taken months before - were still there! And they were completely undamaged. They were completely unaltered, and it was exactly the same pieces of garbage that could be identified. So the slope was, one, not altered, and two, had not been affected by radiation. So the unavoidable conclusion is that there could have not been a big fire in that dump.

After one hour, I came out. And immediately the media started making an enormous deal about the fact that I walked in, spent an hour in the dump, and then I went and refuted the historical truth.

We asked José to discuss the historical truth and the evidence needed to support it.

The historical truth had a basic premise, and the basic premise was that the 43 students were incinerated in the dump. They were killed - and the circumstances [of their deaths] go beyond my technical competency - but effectively you had 43 corpses that had to be incinerated. OK? Not only did they have to be incinerated, the only piece of evidence that existed where they could have found any traces of DNA was a calcinated bone that they identified as one of the students. […] All the other bones were so burned that they had no traces of DNA, no organic matter at all. It was just purely a bone. So that was key. To be able to incinerate a body to that level of destruction, you need an enormous amount of fire. You not only need a very large fire in size - because it has to be much bigger than the body - but you have to have a sufficient amount of fuel that basically evaporates all the water in the body, which is a lot, burns all the organic matter in the body, to the point that there's absolutely nothing left. So you have to have the temperatures incredibly high for a very long period of time.

So we did a whole survey of crematoria to try to establish what was the level of energy that you need to cremate a body to that level. We looked into historical pyres, and we looked into a whole array of information, and we came to the conclusion that to be able to incinerate a body like that - and particularly to be able to incinerate 43 bodies - you know, you needed a fire that was basically enormous. It would have to be hundreds of feet in length and many feet in width and it would have required about 700-800 kilograms of wood per body. So you were talking about tons of timber that had to be put in there to be able to create that fire. And the fire would have been so large in nature that you would have seen it miles away and it would have completely incinerated all the garbage on the slope. So basically the historical truth existed on the premise that 43 bodies were incinerated to a level that there was no organic matter left in that dump.

After José left Mexico, he conducted a series of tests using pig cadavers to prove his analysis of the fire at the Cocula dump.

Pigs are the animal that closest resemble humans when it comes to its reaction to a fire. So many times when people are trying to study skin burns or anything due to fires, they will use pigskin as a surrogate for human skin. And so we decided to seek approval to be able to do these tests with these animals. What the tests demonstrated - which was the first time anybody had done a study with multiple bodies - was that the greater the number of bodies you put in there, the more difficult it was to burn them and therefore the more fuel you need. The studies showed that you needed between seven or 800 kilograms of fuel to be able to fully incinerate one body. If you're going to be burning multiple bodies next to each other, you're going to need more than that amount. We went from one to two, three, four, you know, started increasing the number of animals, and you can see very rapidly that it becomes more and more and more difficult.

José’s conclusions were included in the first report of the group of experts (GIEI) and made public in September 2015. The findings of the GIEI in general - and José’s work in particular - produced a huge backlash.

[My work] was meant to be information for the [GIEI] so that they could understand and get an objective and impartial explanation of the evidence. I did a detailed analysis of the PGR’s reports and showed all the mistakes they had made. Clearly, the people who actually did their analysis had no understanding of fire. [...] My report is just an appendix [to the GIEI’s], with a single and very simple conclusion that says: stop looking in the dump and start looking elsewhere. It was 100 percent technical. But of course it became a scandal, because it was the one piece of evidence that challenged directly the historical truth. And therefore, for those who still believed in a historical truth, it needed to be debunked. [...] Now, everything else that was constructed around it was just simply the equivalent of not reading the report at all. Nobody actually read the report. The media never bothered trying to educate themselves about the report. [...] All they said was, José Torero is wrong, you know, he is just this Peruvian who spent one hour in the dump and he has no idea.

Finally, we asked José to describe his motivation for agreeing to participate in the Ayotzinapa case.

As any human being, I have my political opinions, but as a scientist, I have none. So when I walked into that case, I was not going against the Mexican government, I was not on the side of the Human Rights Commission [GIEI]. Literally my job was purely to reveal what was the scientific basis behind a proper interpretation of what had happened in that dump. And if the conclusion had been that a fire of that nature could have happened in that place and it could have incinerated the people, that's exactly what I would have said. But the conclusion said completely the opposite.