Architect of the Memorial Society, Indefatigable Historian of State Terror, Courageous Soviet Dissident, Inspiration and Partner to the Archive

Washington, D.C., December 20, 2017 – The National Security Archive mourns the passing this week of our dear friend, colleague, and inspirational partner Arseny Borisovich Roginsky, a founder and leader of the Memorial Society in Moscow. Memorial’s Web site announced his death from cancer on December 18, at age 71.

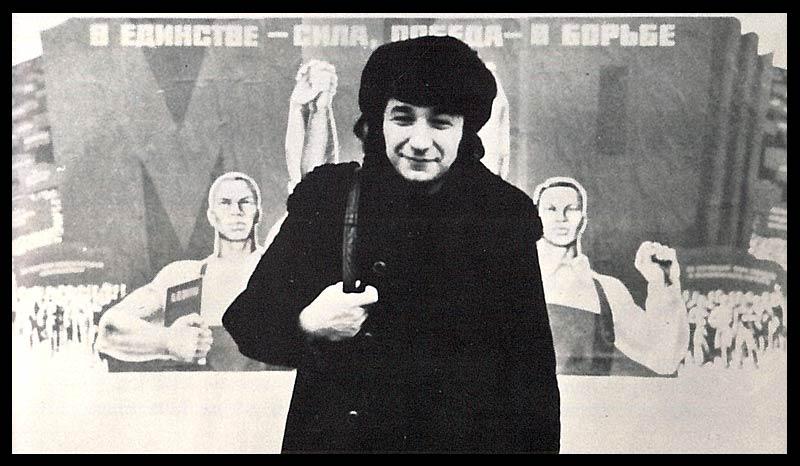

Arseny Roginsky was born in political exile in the small northern town of Velsk, Russia, where his family was sent after his father’s conviction during Stalinist purges. Boris Roginsky was soon arrested again and died in the camps in 1951. Thus, the greatest historian and guardian of public memory of repression in Russia was born into that history.

As a student of the famous cultural historian and literary philosopher, Yury Lotman, at Tartu University in Estonia, Arseny Roginsky researched the Decembrists and opposition movements of the XIX century in Russia, then worked as a teacher in a public school for the next 10 years. While he continued his research on the XIX century in the Leningrad state archives, he became interested in documents of the XX century and Stalin’s repressions. A dedicated archivist, Roginsky started collecting his own archive of repressions in the early 1970s and began publishing a samizdat journal “Pamyat” (Memory).

In 1981, he was arrested and charged with using fake documents to work in the archives, and sentenced to 4 years in the camps, where he served his full term. Upon his release, Roginsky passionately engaged with the spirit of perestroika, sharing with new Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev the idea – indeed the necessity – to fill in the “blank spots of history,” those that had been erased by the Communist Party. In 1988, he co-founded the Memorial Society, which took a leading role in the recovery of history, the commemoration of victims, and the defense of human rights during the final years of the Soviet Union and in the new Russian Federation. Roginsky remained Memorial’s true leader, and at the end of his life was chairman of the society.

When National Security Archive staff first came to the former Soviet Union in 1992 and 1993, Roginsky was already legendary for his documents focus and his investigative research. We first met Arseny Borisovich among piles of documents and photocopies he had collected, ranging from execution orders signed by Stalin to handwritten memoirs on sheets of toilet paper smuggled out of the gulag. We always saw him on the cutting edge of history and memory work, cooperating and consulting with journalists, scholars, victims’ families, human rights advocates, investigative committees of the Supreme Soviet and the Duma, the ombudsman’s office, heads of the state archival organizations, and everyone who could advance the search for evidence and truth.

By 1996, the Archive was bringing declassified U.S. documents and modest grant funding to support a series of projects led by Arseny Borisovich at Memorial. We are very proud to have played a small supporting role with landmark Memorial publications such as the multi-volume series of biographies and photographs of NKVD and KGB agents, drawn from an extraordinary Communist Party dataset discovered by Roginsky in the Party’s personnel files, vetting the secret police officials for each and every promotion.

We are likewise proud to have contributed to Memorial’s Dictionary of the Gulag, a volume giving the history, population, directors, charters, and governing orders of every camp in the gulag archipelago from 1923 to 1960. Painstakingly gathered over years of effort, this data has underwritten every modern account of the prison camps, and establishes a baseline of knowledge that can never be erased. It was an honor to receive from Arseny Borisovich personally the extraordinary Memorial publication of Boris Sveshnikov’s Camp Drawings, remarkable pen-and-ink (occasionally brush) works from inside the camps by art student Sveshnikov – falsely accused of anti-Soviet conspiracy – during his 8 years' imprisonment starting in 1946.

Working with Roginsky, the Archive also supported the creation of an index for the digital edition of the famous samizdat Chronicle of Current Events, and a series of test cases using the Russian access to information act to test openness in regional and local Russian archives. Memorial also co-sponsored the Archive’s 2011 conference at the Gorbachev Foundation in Moscow, focused on the years 1989-1991, and combining highest-level state documents from Soviet and U.S. files with presentations by scholars, veterans and activists on both Gorbachev’s and civil society’s role in the transformation of the Soviet Union in those years.

On all our joint projects, the original idea practically always came from Arseny Borisovich. He guided each of the projects thoughtfully and carefully, devoting much of his personal time and infectious energy to our joint work. He also found time to take part in our multi-year project on freedom of information and access to the archives in the former Soviet republics, attended numerous conferences with us in Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, and worked in the Georgian security archives with our Georgian colleagues. His commitment and reputation were a guarantee of success for these conferences because participants understood that if Roginsky was involved, the conversation would be honest, comprehensive and balanced. We and our partners treasure the memory of our work with Arseny Borisovich.

In September 2011, at the end of a two-year project with Memorial, we organized a public launch in Moscow of a new Web-portal titled “Carter and Soviet Dissidents” and featuring declassified U.S. and Soviet documents. In attendance were many leading Soviet dissidents including Lyudmila Alexeyeva and Sergey Kovalev. Arseny Borisovich was the brain behind the portal and the main speaker at the launch – the Web publication remains as a permanent Roginsky legacy.

In 2012, at Roginsky's invitation, we had the unique opportunity to attend what would become the last convention of Pilorama, which would be shut down by the authorities in 2013. This history, music and living witness festival was held annually starting in 2005 at the Museum Perm-36, one of the few surviving former gulag camps (which held prisoners as late as 1987), ultimately preserved by the efforts of the local Memorial chapter with Roginsky’s strong support. The name Pilorama referred to the logging operations previously run by the prisoners. We saw some 3,000 young people camped out in the fields next to the camp in chilly and rainy weather. They had come to listen to real former prisoners of Perm-36, leading human rights advocates, legendary bard singers and rock bands, and even judges of the Constitutional Court. Everyone participated in the debates about historical memory and the current struggle for human rights in Russia. We were fortunate to be part of an unforgettable tour of the camp barracks led by Arseny Borisovich himself.

When Memorial was named a “foreign agent” by the state in 2016, Roginsky continued his work in challenging conditions but was not willing to slow down the struggle for preserving Russian historical memory against the prevailing politics of glorification of the Soviet past. He believed that “we got stuck in the long period” when unfavorable conditions were unlikely to change soon, and that historians needed to learn perseverance and use all the opportunities still available to work with original sources and publish true information on the great terror.

It is hard to believe that on our next trip to Moscow, we will not be able to come to Arseny Borisovich for advice, drink his strong French press coffee in espresso cups in his office, and accompany him outside on his smoking breaks. We will deeply miss his very literary, ironic and funny commentary on recent developments in Russia.

For more than two decades, he was our source of inspiration and ideas about specific projects that took off thanks to his precise understanding both of what needed to be done and what could be done as Russian public space was shrinking. He was a dissident to the core, a great intellectual with a critical view of his country, who deeply cared about the society and its historical memory.

Yet his opposition was not obstructionist, he was always willing to work with authorities and other political forces on projects and issues that could produce substantive results, such as memorials to the victims of repression in every form. Those who walk up Tverskaya Street in downtown Moscow today can see one of Roginsky’s powerful legacies on almost every apartment building entrance: the small metallic plaques remembering the victims of state terror who were disappeared from that building, with a hole where the photograph would be, listing on each one a name with the person’s occupation, date of arrest, sentence, date of execution, and date of rehabilitation.

Arseny Roginsky will forever live in our memories.

- Svetlana Savranskaya and Tom Blanton