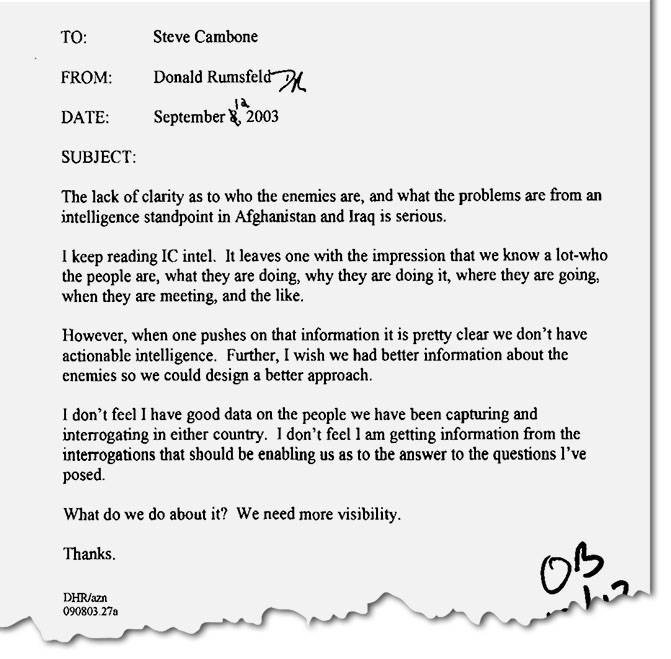

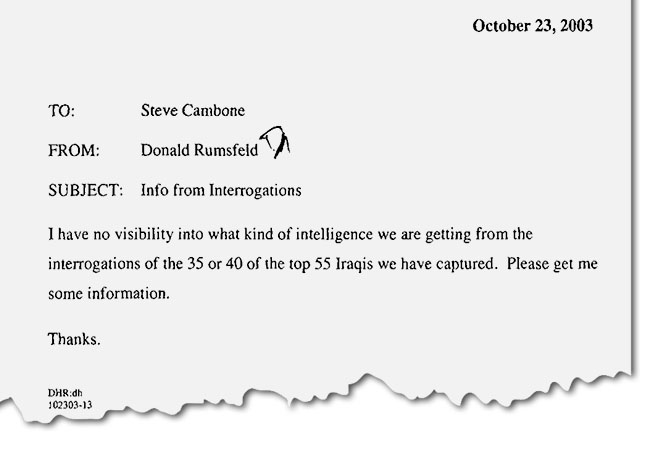

Washington, D.C., February 1, 2021 – On September 9, 2003, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld wrote to Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence Steve Cambone expressing concern about information from interrogations at military sites in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Secretary wrote, “The lack of clarity as to who the enemies are, and what the problems are from an intelligence standpoint in Afghanistan and Iraq is serious.” Six weeks later, on October 23, 2003, Rumsfeld followed up: “I have no visibility into what kind of intelligence we are getting from the interrogations of the 35 or 40 of the top 55 Iraqis we have captured. Please get me some information.”

These memos – and tens of thousands of others known as “snowflakes” – have been declassified thanks to a 2017 Freedom of Information Act lawsuit filed by the National Security Archive with pro bono representation from the law firm of Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom. The first 20,975 pages have recently been published in the latest Digital National Security Archive (DNSA) subscription set in conjunction with the scholarly publisher ProQuest, under the title Donald Rumsfeld’s Snowflakes, Part 1: The Pentagon and U.S. Foreign Policy, 2001-2003. The collection reveals a dynamic portrait of the daily workings of the Pentagon and secretary of defense throughout the security-driven first term of the George W. Bush presidency.

Today the Archive is posting 35 of the most notable items from the new collection. A follow-on DNSA publication covering the rest of Rumsfeld's tenure as secretary will appear through ProQuest later in 2021.

One such snowflake was written on March 3, 2003. At 8:16 AM, Rumsfeld wrote to Senior Military Assistant LTG Bantz J. Craddock and Department of Defense General Counsel William Haynes with the subject “KSM''. He wanted to know, “Do we know where the information to find Khalid Sheikh Mohammed came from? Was it from GTMO detainees?” There is no response from either Craddock or Haynes in the DOD release to the Archive, though Rumsfeld’s question is likely a push back to the false claims made by CIA Director George Tenet that the Agency’s resort to torture of Abu Zubaydah led to the capture of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed.

The Senate Select Committee on Intelligence torture report would later reveal that key intelligence on KSM as the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks came from the FBI’s non-coercive, rapport-building interrogation of Abu Zubaydah.[1] This success was prior to the CIA’s contract psychologists, James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen, taking over the interrogation at the CIA “Detention Site Green” in Thailand, which was created to house Zubaydah in 2002. Their approach to Zubaydah would include 83 water board sessions yet fail to produce any valuable intelligence. CIA clandestine services chief Jose Rodriguez (and perhaps Gina Haspel, who would later become DCI, though CIA redactions of documents continue to obscure her role) ordered the destruction of the torture videotapes, commenting that “the heat from destoying [sic] is nothing compared to what it would be if the tapes ever got into public domain.”

Later on March 3, under the subject “Contingencies”, Rumsfeld wrote to Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Doug Feith, stating, “We need to plan what we will do if Saddam Hussein is captured. We need to plan what we will do if we catch an imposter.” There is no record of Feith’s answer in the DOD release to the Archive.

Throughout Rumsfeld’s tenure, his snowflakes circulated daily through the highest levels of the Pentagon. With scant limitations on their subject matter, the all-encompassing documents are sometimes an hourly paper trail inside the Office of the Secretary of Defense during six years of tremendous consequence for U.S. foreign policy. The declassified documents also provide an account that at times contradicts DOD public statements. For example, The Washington Post published a selection of the memos in the six part series “The Afghanistan Papers'' in September 2019 revealing that officials misled the American public about the war in Afghanistan.

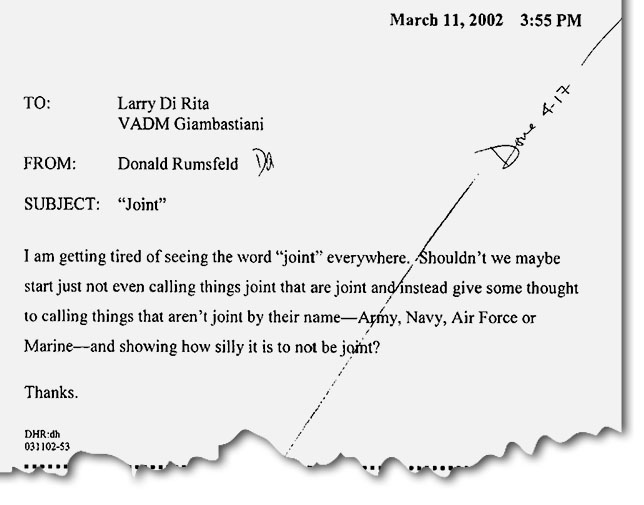

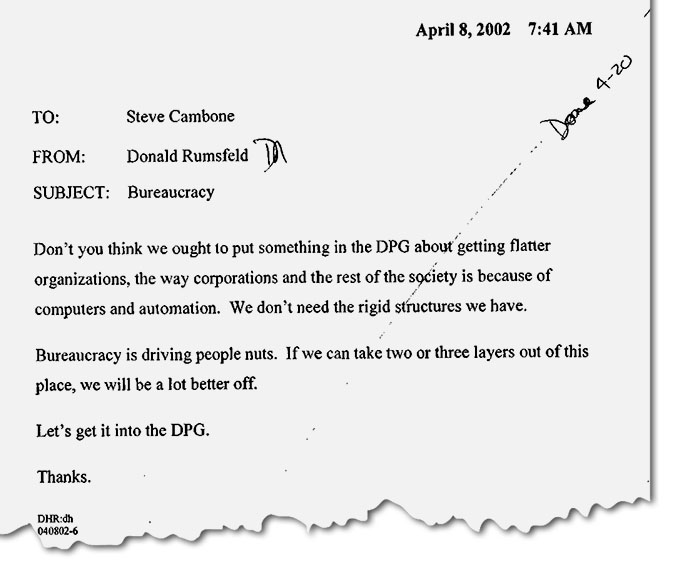

The entire corpus of snowflakes also details many aspects of the day-to-day operations of the Pentagon, the modernization of the U.S. armed forces, and Rumsfeld’s personal agenda against bureaucracy. “Bureaucracy is driving people nuts,” he wrote in an April 8, 2002, memo at 7:41AM. “If we can take two or three layers out of this place, we will be a lot better off.” In a separate April 8 letter, the secretary suggested cutting all major Pentagon programs by at least 20 percent. (The DOD budget increased by 37.54 percent between FY2001 and FY2006.) On March 11, 2002, Rumsfeld wrote to colleagues, “I am getting tired of seeing the word ‘joint’ everywhere.”

Other topics in the collection include:

- the military budgeting process and efforts to rein in defense spending;

- military planning, procurement, and expenditures;

- nuclear issues – weapons, proliferation, safety;

- decision making on military wages, benefits, tours of duty, and veterans issues;

- military intelligence;

- Defense Department relations with the CIA and Homeland Security;

- Rumsfeld’s relations with the State Department and National Security Council;

- U.S. relations with NATO;

- U.S. military relations with Russia, former Soviet republics, and other countries;

- Rumsfeld’s interactions with the news media, Congress, and the public;

- Guantanamo detainees, interrogation, and torture;

- concerns about the International Criminal Court and U.S. liability for war crimes;

- the hunt for Osama bin Laden and other terrorists;

- the Joint Strike Fighter program; and

- the emergency landing of a U.S. EP-3 at Hainan Island in 2001

Donald Rumsfeld’s Snowflakes, Part 1: The Pentagon and U.S. Foreign Policy, 2001-2003 will be a critical research tool for historians and will be available through many college and research libraries. Part II, which covers the last three years of Rumsfeld’s tenure as secretary of defense from 2004 to 2006, will be published in 2021. Learn more about accessing the Digital National Security Archive through your library online and how to request a free trial here.

Notes

[1] United States., & Feinstein, D. (2014). The Senate Intelligence Committee report on torture: Committee study of the Central Intelligence Agency's Detention and Interrogation Program (*see page 46).