Washington, D.C., October 3, 2022 - Sixty years ago, on October 1, 1962, four Soviet Foxtrot-class diesel submarines, each of which carried one nuclear-armed torpedo, left their base in the Kola Bay, part of the massive Soviet deployment to Cuba that precipitated the Cuban Missile Crisis. An incident occurred on one of the submarines, B-59, when its captain, Valentin Savitsky, came close to using his nuclear torpedo. Although the Americans weren’t even aware of it at the time, it happened on the most dangerous day of the crisis, October 27. The episode has since become a focus of public debate about the dangers of nuclear weapons and has inspired many sensationalist accounts.

Today, the Archive marks the 60th anniversary of the underwater Cuban Missile Crisis by publishing for the first time in English the only public recollection of Vasily Arkhipov, the submarine brigade’s chief of staff, who was on board B-59 at the critical moment and helped Captain Savitsky avoid making the potentially catastrophic decision to launch a nuclear attack. Arkhipov shared his memories of the incident during a presentation at a conference to commemorate the 35th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis held in Moscow on October 14, 1997.

In addition to Savitsky’s recollections, today’s posting also features a core collection of previously published records on the underwater Cuban Missile Crisis based on 20 years of research by the National Security Archive.

The Arkhipov presentation implicitly confirms reports that, on the night of October 27, B-59 experienced an extraordinary situation in which the captain could have used a nuclear torpedo against U.S. anti-submarine warfare forces. At the time of the presentation, Arkhipov was the only eyewitness to the events on the conning tower and Savitsky's immediate reactions. His presentation was revealing even as he tried to avoid addressing the key issue—possible use of a nuclear weapon and his own role in resolving the situation.

The 1997 conference was attended by the commanders of the three other submarines of the 69th Brigade—Ryurik Ketov, Nikolay Shumkov and Aleksey Dubivko. Savitsky, the commander of B-59, had already passed away. Arkhipov’s presentation opens with a response to the 1995 publication by journalist Alexander Mozgovoy in Komsomolskaya Pravda about the near-use of a nuclear-tipped torpedo by the captain of B-59. Mozgovoy’s account was based on his interviews with Vadim Orlov, head of the radio intercept unit on B-59. Before Mozgovoy’s publication, the information about the incident had been kept secret. Arkhipov’s presentation was intended to provide the official public story, which, on the one hand, confirmed the details of the incident, but, on the other, never mentioned the word “nuclear” except in reference to Mozgovoy’s headline.

According to Arkhipov’s report, when the submarine surfaced on the night of October 27 to charge its batteries, the commander, Savitsky, who went up to the conning tower with Arkhipov, was shocked and blinded by the unexpected actions of U.S. antisubmarine warfare ships and planes (described by Arkhipov as “overflights by planes just 20-30 meters above the submarine’s conning tower, use of powerful searchlights, fire from automatic cannons (over 300 shells), dropping depth charges, cutting in front of the submarine by destroyers at a dangerously [small] distance, targeting guns at the submarine, yelling from loudspeakers to stop engines.") Arkhipov offers us a chilling counterfactual—the commander could have ordered an emergency dive and, thinking that he was under attack, could have used nuclear weapons against the attacker.

The accounts of Orlov and Ketov—and later Anatoly Leonenko and Viktor Mikhailov, who were commander of torpedo unit #3 on B-59 and head of the combat navigation group, respectively—(none of whom witnessed the exchange on the conning tower) confirm that Savitsky did, in fact, order the dive and call for the launch of the sub’s nuclear torpedo. Additional recollections of the incident were later published by surviving submariners in a volume edited by Admiral V.V. Naumov, Карибский кризис. Противостояние. Сборник воспоминаний участников событий 1962 года.

In an interview with Svetlana Savranskaya on July 12, 2012, Ketov said that Savitsky did indeed think that they were under attack and that the war with the United States had already started. Caught off guard by the aggressive U.S. actions, Savitsky panicked, calling for an “urgent dive” and the preparation of torpedo #1 (with the nuclear warhead), but he was unable to quickly descend the narrow stairway of the conning tower, which was temporarily blocked by the signaling officer and his equipment. Arkhipov, who was still on the tower and saw that the Americans were actually signaling, not attacking, called the commander back and calmed him down. Savitsky’s command was never transmitted to the officer in charge of the torpedo, and the Soviet submarine signaled back to the Americans to cease all provocative actions. The situation was defused, and the next day, the B-59, with fully charged batteries, was able to submerge without warning and evade its pursuers.

The submarine commanders tried to suppress the story of the incident on B-59 for almost 40 years. The 40th anniversary conference in Havana, organized by the National Security Archive in October 2002, made the B-59 story a focus of public debate, leading to further revelations, most importantly by Orlov (who attended the 2002 event) and Ketov. The Archive thanks the Submarine Veterans Club of St. Petersburg and its council chairman, Igor Kurdin, for their cooperation over the years. Further details of this story will emerge when Russian documents relating to Operation Kama, the submarine deployment, are declassified.

The Documents

Document 1

Kirov Naval Academy (National Naval Academy, Baku) website, downloaded in 2014

This presentation is the only known public statement by Vasily Arkhipov about the events on submarine B-59 during the Cuban Missile Crisis. It is clear that he is very unhappy about journalist Alexander Mozgovoy’s revelation (based on Vadim Orlov’s account) of the near-use of the nuclear torpedo, which he sees as part of the plot to “denigrate and defame prominent Soviet military and naval leaders” and “destroy the Soviet Armed Forces.” Arkhipov describes the events of October 27, when his submarine had to surface because of exhausted batteries while being pursued by U.S. anti-submarine forces. In his account, the captain, Savitsky, was “blinded” and shocked by the bright lights and sounds of explosions and “could not even understand what was happening” as he came up on the conning tower. Arkhipov gives his audience a hypothetical: “the commander could have instinctively, without contemplation ordered an ‘emergency dive’; then after submerging, the question whether the plane was shooting at the submarine or around it would not have come up in anybody’s head. That is war.” And in war, the commander certainly was authorized to use his weapons.

Arkhipov does not mention his own role in the critical situation, saying only that in a couple of minutes “it became clear” that the plane fired past and alongside the boat and was therefore not under attack.

Document 2

Donation by Captain Ryurik Ketov to Svetlana Savranskaya, July 2012

This is a draft report prepared for the debriefing on Operation “Kama” in Moscow in early January 1963. The submarine commanders drafted the report in December 1962 as they were preparing to brief top political and military leadership in Moscow. It is safe to assume that Arkhipov probably drafted the text because he was the main presenter in Moscow. The report mentions preparations for the mission, its reduced size, and weather conditions for crossing the Atlantic Ocean. It emphasizes the overwhelming dominance and aggressive actions of U.S. anti-submarine forces (“a hundred times stronger than ours in their combat capabilities”) against B-36, B-59 and B-130, which had to surface for repairs and to charge their batteries. The report mentions that B-36 was attacked by a torpedo, but that it missed the boat because it was submerging very fast. The report is completely silent about any incidents on B-59, which implies that at the time of the drafting of the report, the commanders intended to keep the information secret.

Previously published documents

National Archives, RG 330, Sensitive Records on Cuba, box 1, Cuba 381 (20-25 October 1962)

This notice provides submarine surgacing and identification procedures in the general vicinity of Cuba.

Donation to Svetlana Savranskaya

This report concerns participation of submarines 'B-4,' 'B-36,' 'B-59,' 'B-130' of the 69th submarine brigade of the Northern Fleet in the Operation 'Anadyr' during the period of October-December, 1962.

Digital image by Svetlana Savranskaya

Digital image by Svetlana Savranskaya

Excerpt of diary entry for Anatoly Petrovich Andreyev, October 1962.

Alexander Mozgovoi, The Cuban Samba of the Quartet of Foxtrots: Soviet Submarines in the Caribbean Crisis of 1962 (Moscow, Military Parade, 2002). Translated by Svetlana Savranskaya, National Security Archive.

Orlov's account includes the controversial depiction of an order by Captain Valentin Savitsky to assemble the nuclear torpedo.

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

This cable reports seven SOSUS contacts with conventional Soviet submarines, although noting the difficulty of using SOSUS to track submarines C-18 and C-19.

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

Reports various visual sightings and various technical intelligence contacts of Soviet submarines through radar, SOSUS, MAD, as well as Julie and Jezebel sonobuoys.

National Archives, Record Group 24, Records of Bureau of Naval Personnel (hereinafter cited as RG 24), Deck Logs 1962, box 74

The deck log book for U.S.S. Beale shows tracking and signaling operations, with use of practice depth charges (PDCs), and eventual surfacing of submarine C-19 on the evening of 27 October (local time). The Beale was part of the Randolph ASW Task Group 83.2.

RG 24, Deck Logs 1962, box 178

The deck log book for the U.S.S. Cony, which was also part of TG 83.2, shows its role in tracking, signaling, and surfacing submarine C-19 (B-59).

RG 24, Deck Logs 1962, box 57

Deck log book for U.S.S. Bache, which tracked C-19 (identified as PROSNABLAVST) on 28 October.

RG 24

Deck log book for U.S.S. Barry, which tracked C-19 (PROSNABLAVST) on 29 October.

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

This cable describes C-19 as "raising and lowering masts and snorkel indicating hydraulic difficulties and/or repairs."

I. Soviet Plans to Deploy Submarines

1

Volkogonov Collection, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Reel 17, Container 26. Translated by Gary Goldberg for the Cold War International History Project and the National Security Archive.

This report describes arrangements to send a squadron of submarines to Cuba, including a brigade of torpedo submarines and a division of missile submarines, with two submarine tenders.

2

Volkogonov Collection, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Reel 17, Container 26. Translated by Gary Goldberg for the Cold War International History Project and the National Security Archive.

This report on the progress of Operation Anadyr, 25 September 1962, indicates plans to equip the submarine brigade with one nuclear torpedo on each submarine, and to send a nuclear attack submarine to protect the transport ship Aleksandrovsk.

II. Cables, reports, deck logs, and after-action reports on U.S. ASW operations

01

Philip Zelikow and Ernest R. May, editors. The Presidential Recordings John F. Kennedy, The Great Crises, Vol. III (New York, W.W. Norton, 2001), pp. 190-194; John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, MA.

President Kennedy and his advisers discussed the Soviet submarine problem and the Navy's procedures for signaling the submarines with practice depth charges during this meeting.

02

Washington Navy Yard, Naval Historical Center, Operational Archives Branch, Cuba History Files, Boxes 68-71, file: 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1 (hereinafter cited as CHF, with file name)

This cable reports a "probable" submarine sighting (probably C-18) and requests patrol flights to find the submarine.

03

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

This message assigns the effort to track C-18 the "highest priority", with a patrol squadron VP 45 assigned the task on a "continuing basis."

04

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

Notes that ASW squadron "Woodpecker Nine" made a visual sighting of a Soviet Foxtrot submarine, probably C-18.

05

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

This cable reports a visual sighting of C-18 (Soviet submarine B-130).

06

Washington Navy Yard, Naval Historical Center, Operational Archives, Flag Plot Cuba Missile Crisis 31-2, file: Misc. Information

A chronology of major events recounts the blockade and ASW efforts as well as the preparation of forces for an invasion of Cuba.

07

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

This cable confirms that submarine C-18, identified with hull number 945, dove after a sighting by ASW aircraft.

08

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

Reports a sighting by “Woodpecker Five” of a submarine cataloged as C-19 (Soviet submarine B-59). Notes that patrol aircraft maintained "mad contact," that is, contact through magnetic anomaly detection (MAD).[12]

09

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

This cable shows visual sightings and SOSUS (sound surveillance system)[13] contacts with Soviet submarines--including C-18, C-19 (B-59), and C-20--since 22 October.

10

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

Summarizes "current ASW activity" in the vicinity of Guantanamo Bay (GITMO).

11

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

This cable reports seven SOSUS contacts with conventional Soviet submarines and noted the difficulty of using SOSUS to track C-18 and C-19 (B-59).

12

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

Reports various visual sightings and various technical intelligence contacts of Soviet submarines through radar, SOSUS, MAD, as well as Julie and Jezebel sonobuoys.[14]

13

National Archives, Record Group 24, Records of Bureau of Naval Personnel (hereinafter cited as RG 24), Deck Logs 1962, box 74

The U.S.S. Beale deck log book shows tracking and signaling operations with the use of practice depth charges (PDCs) and the eventual surfacing of submarine C-19 (B-59) on the evening of 27 October (local time). The Beale was part of the Randolph ASW task group 83.2.

15

RG 24, Deck Logs 1962, box 57

This is the deck log book for U.S.S. Bache, which tracked C-19 (identified as PROSNABLAVST) on 28 October.

16

Alexander Mozgovoi, The Cuban Samba of the Quartet of Foxtrots: Soviet Submarines in the Caribbean Crisis of 1962 (Moscow, Military Parade, 2002). Translated by Svetlana Savranskaya, National Security Archive.

Vadim Orlov's account includes the controversial depiction of an order by Captain Valentin Savitsky to assemble the nuclear torpedo.

17

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

This cable reports that SOSUS system "total remaining above normal", including 6 contacts of Soviet conventional submarines: C-18, C-19 (B-59), C-20, and C-23.

18

RG 24

This is the deck log book for the U.S.S. Barry, which tracked C-19 (PROSNABLAVST) on 29 October.

19

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

Cable describes C-19 (B-59) as "raising and lowering masts and snorkel indicating hydraulic difficulties and/or repairs."

20

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

Reports that the U.S.S. Barry lost contact with C-19 (B-59) after it "went deep."

21

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

The cable reports surfacing of Foxtrot submarine C-18 (B-130), side number 945, late in the evening of 29 October at 2310Z (Greenwich meridian time).

22

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

Reports that C-18 "remaining on the surface."

23

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

This cable reports that C-18 [B-130] submerged early in the morning at 3000622Z, but that destroyers and aircraft were holding sonar (sound navigation and ranging)[15] and MAD contacts.

31

CHF, 21.SS/ASW

Reports on surfacing of C-26 [B-36] at 11054Z. The U.S.S. Cecil monitors the submarine, whose crew was "taking turns airing topside." The term "xmas" found in paragraph 4 stands for "unknown non-American submarine."

24

CHF, 21.SS/ASW

U.S.S. Speed cable on MAD and sonar contacts with Soviet submarine C-26 (B-36), although "have not attempted special surfacing signals viewed as part of lifted quarantine."

25

CHF, 21.SS/ASW

This cable reports B-36 [C-26]'s "strong attempt [to] break contact ... in radical course changes and speeds to 15 [knots] and false echo cans."

26

CHF, 21.SS/ASW

The cable reports that contact was evaluated as "submarine" in light of 30 MAD contacts by patrol aircraft. "Maintaining continuous sonar contact" of C-26 [B-36].

27

CHF, CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-1

This reports the surfacing of C-18 [B-130] after 14 hours of continuous contact by destroyers and patrol aircraft. "Sub was evasive using decoys, depth changes, backing down" but "sonar contact [was] never lost." After surfacing, the submarine stated its number as 945 and stated that it needed no assistance.

28

RG 24, Deck Logs 1962, Box 91.

This is the deck log book for U.S.S. Blandy, which played a critical role in the surfacing of C-18 (B-130).

29

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-2

This cable reports on radar and visual sighting of submarine cataloged as C-21 (possibly Soviet submarine B-4).(16)

30

CHF, 21.SS/ASW

This cable recountsefforts to hold contact with submarine C-26 [B-36] whose "evasive tactics" were increasing. "Submarine launched false target cans at least three occasions."

32

On the Edge of the Nuclear Precipice (Moscow: Gregory Page, 1998). Translated by Svetlana Savranskaya

This is a translation provided by Svetlana Savranskaya of Dubivko’s “In the Depths of the Sargasso Sea.”

33

CHF, 21.SS/ASW

Reports high detection visibility although a decrease in SOSUS contacts.

34

CHF, 21.SS/ASW

This reviews previously reported and new submarine contacts through Jezebel, LOFAR (low frequency analysis and recording), and other detection systems.

35

CHF, 21.SS/ASW

This cable reports that the Cecil is keeping watch of C-26 [B-36], whose crew "worked on fittings under superstructure deck." C-26 submerged later in the day (see document 36).

36

RG 24, 1962 Deck Logs, box 467

This is the deck log book for U.S.S. Keppler, which monitored C-18 in early November.

37

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)-2

Cable provides status report on contacts with C-21: "our attitude has changed from confidence to frustration to doubt as the nature of the contacts varied. My present evaluation [is] that the original contact was a positive sub sighting."

38

CHF, 21.SS/ASW

This cable reports on the status of C-18, C-19 (B-59), C-21, and C-26, among other contacts.

39

CHF, 21.SS/ASW

This cable reports on unsuccessful efforts to track C-21.

40

CHF, 21.SS/ASW 2

This special reports confirms sightings of Soviet submarines, but notes that contact C-21B is "tentative" because of a "lack of confirming evidence."

41

CHF, 21.SS/ASW 2

Cable reports status of C-18, C-19 (B-59), C-21, and C-26

42

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)

This cable recounts continuing efforts to track C-21, as well as the possible detection of a nuclear submarine through LOFAR and ECM (electronic countermeasures).

43

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)

Reports on the continued monitoring of C-18 (B-130), which appears to be experiencing "mechanical difficulty in separating fuel from water for diesel engines."

44

CHF, 21.SS/ASW

This cable reports the rendezvous by C-18 (B-130) with an unidentified surface ship, probably the Russian tugboat, Pamir.

45

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts (Closed)

Reports on C-18's unsuccessful attempts to submerge.

46

CHF, 21 (A) SS/ASW Contacts

This cable reports that if the Soviet tugboat Pamir is escorting C-18, and both "are homeward bound", the surveillance operation will soon end. As it turned out, the Pamir towed C-18 (B-130) back to port near Murmansk, a three-week voyage.

47

U.S. Navy Freedom of Information Act Release

This report describes aerial patrol efforts to track C-19 (B-59). During one of the helicopter operations on 27 October, after PDC "surfacing signals exploded," sonar picked up noise caused by hatches slamming shut "leaving no doubt that we had a submarine contact."

48

U.S. Navy Freedom of Information Act Release

This report shows surveillance efforts against Soviet submarine C-26, which surfaced because its "undersea capability ... had been evidently exhausted through continued restriction of its movement by air and surface units since the evening of 29 October 1962."

49

Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Atomic Energy, "History of the Custody and Deployment of Nuclear Weapons (U), July 1945 - September 1977," February 1978, Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release

This table shows the deployment of non-nuclear components of nuclear depth charges at Guantanamo Bay.

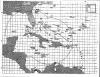

III. Charts

The following charts showing ship deployments and movements on each day of the Cuban missile crisis were the work of "Flag Plot" and "ASW plot," special components of the office of the Chief of Naval Operations. With these charts, formerly classified "Top Secret", one can track the massive buildup of blockade and invasion forces during the days after 22 October as well as the systematic effort to locate Soviet submarines and other Soviet ships. As the intensity of the crisis grew, the demands of senior officials for more timely information led Flag Plot to produce these charts four times daily; as the crisis ebbed, however, charts were produced only once a day. As the details of submarine sightings accumulated, by the end of October CNO staffers began to produce a daily "ASW Plot" chart that included brief summaries of encounters with Soviet submarines.

Source for charts: Washington Navy Yard, U.S. Naval Historical Center, Operational Archives, "Flag Plot Cuban Missile Crisis" files: "Op-Sum Oct 62" and "Op-Sum Nov 62"