Washington, D.C., August 19, 2021 – The U.S. government under four presidents misled the American people for nearly two decades about progress in Afghanistan, while hiding the inconvenient facts about ongoing failures inside confidential channels, according to declassified documents published today by the National Security Archive.

The documents include highest-level “snowflake” memos written by then Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld during the George W. Bush administration, critical cables written by U.S. ambassadors back to Washington under both Bush and Barack Obama, the deeply flawed Pentagon strategy document behind Obama’s “surge” in 2009, and multiple “lessons learned” findings by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) – lessons that were never learned.

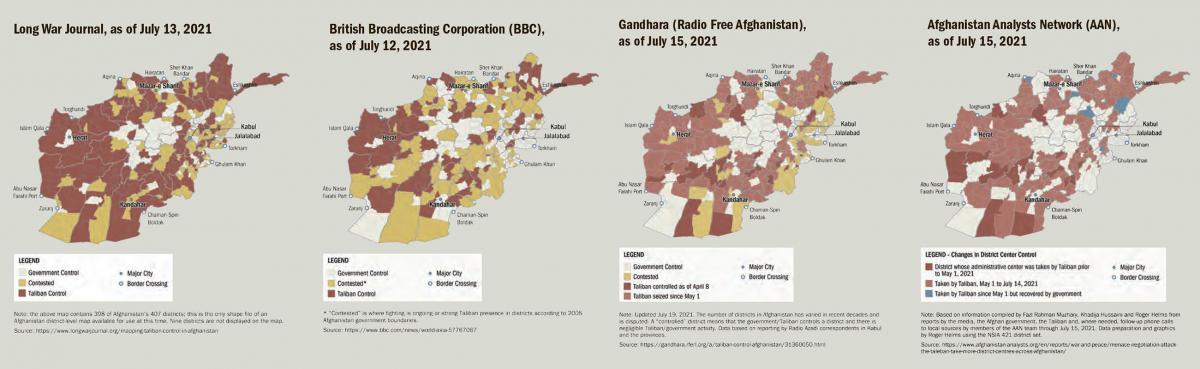

Estimates of Taliban controlled districts in Afghanistan as of mid-July 2021 ranged as high as more than half, according to the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, Quarterly Report, July 31, 2021, p. 55. The number had increased from 73 in April to 221 in July, a harbinger of the August takeover in Kabul.

The recent SIGAR report to Congress, from July 31, 2021, just as multiple provincial centers were falling to the Taliban, quotes repeated assurances from top U.S. generals (David Petraeus in 2011, John Campbell in 2015, John Nicholson in 2017, and Pentagon press secretary John Kirby in 2021) about the “increasingly capable” Afghan security forces. The SIGAR ends that section with the warning: “More than $88 billion has been appropriated to support Afghanistan’s security sector. The question of whether that money was well spent will ultimately be answered by the outcome of the fighting on the ground, perhaps the purest M&E [monitoring and evaluation] exercise.” Results are now in with the total collapse of the Afghan government and a looming humanitarian crisis.

The documents detail ongoing problems that bedeviled the American war in Afghanistan from the beginning: lack of “visibility into who the bad guys are;” Pakistan’s double game of taking U.S. aid while providing a sanctuary to the Taliban; “mission creep” as a counterterror effort against al-Qaeda morphed into a nation-building war against the Taliban; Washington’s attention deficit disorder as the Bush administration pivoted to invading and occupying Iraq; endemic corruption driven in large part by American billions and secret intelligence payments to warlords; fake statistics and gassy metrics not only by the military but also the State Department, US AID, and their many contractors; the mismatch between Afghan realities and American designs for a new centralized government and modernized army; and more.

Read the Documents

Document 1

Digital National Security Archive, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit

This is the foundational document for the first phase of U.S. strategy in Afghanistan, approved by the National Security Council on October 16, 2001 (just five weeks after the 9/11 attacks). This copy carries Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld’s personal handwritten edits, with an October 30 cover note to his top policy aide Douglas Feith about crafting a new updated version, emphasizing that "The U.S. should not commit to any post-Taliban military involvement since the U.S. will be heavily engaged in the anti-terrorism effort worldwide." The follow-on peacekeeping force in Afghanistan “could be UN-based or an ad hoc collection of volunteer states … but not the U.S.” Rumsfeld adds the word “military” as in “not the U.S. military.” The strategy emphasizes the destruction of al-Qaeda and the Taliban, and is careful not to commit the U.S. to extensive rebuilding activities in post-Taliban Afghanistan. "The USG [U.S. Government] should not agonize over post-Taliban arrangements to the point that it delays success over Al Qaida and the Taliban.” Operationally, the U.S. will "use any and all Afghan tribes and factions to eliminate Al-Qaida and Taliban personnel," while inserting "CIA teams and special forces in country operational detachments (A teams) by any means, both in the North and the South." Diplomacy is important "bilaterally, particularly with Pakistan, but also with Iran and Russia," however "engaging UN diplomacy… beyond intent and general outline could interfere with U.S. military operations and inhibit coalition freedom of action." U.S. bombing began in Afghanistan on October 7, 2001, the special forces teams arrived October 19, and in the second week of November, in a stunning cascade of Taliban surrenders, all major cities except Kandahar fell to the U.S.-backed Northern Alliance. Taliban leaders took refuge mostly in Pakistan but also around Kandahar, Taliban soldiers melted into the population, and the sequence provided almost a mirror image of the rapid August 2021 implosion of the Afghan government and security forces.

Document 2

Digital National Security Archive, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit

Exhilarated by swift victory over the Taliban in late 2001, the Bush administration quickly switched its attention to Iraq, but by March 2002 Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld was worried again about Afghanistan, writing a snowflake to top aides about setting up a weekly meeting because the situation was “drifting.” Later the same day, Rumsfeld would do a long interview with MSNBC, never mentioning his worries about drift, but rather arguing there was no point in negotiating with Taliban remnants – “the only thing you can do is to bomb them and try to kill them. And that’s what we did, and it worked. They’re gone. And the Afghan people are a lot better off.”

Document 3

Digital National Security Archive, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit

On April 17, 2002, President George W. Bush announced new objectives for Afghanistan in a speech at the Virginia Military Institute, including a stable government, a new army, and a new education system for boys and girls. In effect, Bush’s speech revoked the previous Rumsfeld insistence about not committing “to any post-Taliban military involvement.” That same day when the stated U.S. goals moved to nation building, Rumsfeld’s concerns about no clear exit strategy from Afghanistan crystallized in a short snowflake addressed to his top policy aide Douglas Feith and copied to his deputy Paul Wolfowitz and to the chair and vice-chair of the Joint Chiefs. “I know I’m a bit impatient,” he writes, but “We are never going to get the U.S. military out of Afghanistan unless we take care to see that there is something going on that will provide the stability that will be necessary for us to leave.” “Help!”

Document 4

Digital National Security Archive, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit

This Rumsfeld memo to his policy aide, Douglas Feith, on June 25, 2002 captures how naïve top American officials were about Pakistani motivations, and how throwing money at any problem came to be the core U.S. modus operandi around Afghanistan. Rumsfeld asks, “If we are going to get the Paks to really fight the war on terror where it is, which is in their country, don’t you think we ought to get a chunk of money, so that we can ease Musharraf’s transition from where he is to where we need him.” Rumsfeld does not see how Pakistan and its intelligence service were playing both sides in Afghanistan, and the net for Pakistani leader Musharraf was some $10 billion in U.S. aid over the following six years.

Document 5

Obtained through FOIA by the National Security Archive

This 14-page email written between August 11 and August 15, 2002, by a Green Beret member of a commando team hunting “high-value” targets circulated at the highest levels of the Pentagon, not least because of its humor and its candor about actual conditions in Afghanistan, and the author’s previous position as a deputy assistant secretary of defense before his Reserve unit mobilized. Roger Pardo-Maurer opened with his “Greetings from scenic Kandahar” which he went on to describe as “Formerly known as ‘Home of the Taliban.’ Now known as ‘Miserable Rat-Fuck Shithole.” “Kandahar is like sitting in a sauna and having a bag of cement shaken over your head.” To those who call it dry heat, Pardo-Maurer, a member of Yale’s class of 1984, rejoins, “you don’t stay dry for long when you are the Lobster Thermidor inside a carapace of about 50 lbs. of Kevlar and ceramic plate armor, with a sweltering chamber pot on your head.” “If there is a landscape less welcoming to humans anywhere on earth, apart from the Sahara, the Poles, and the cauldrons of Kilauea [Hawaii], I cannot imagine it, and I certainly don’t intend to go there.”

Alluding to the continuing role of Pakistan as a Taliban sanctuary, Pardo-Maurer warned, “The shooting match is still very much on. Along the border provinces, you can’t kick a stone over without Bad Guys swarming out like ants and snakes and scorpions.” He recommends staying with a Special Forces strategy “fighting along the Afghans, rather than against them” – “the number one military mistake we could make here is to ‘go conventional’ in this war.” As for “the number one political mistake,” that would be “to actually believe that this place is a country, and that there is such a thing as an Afghan. It is not, and there is not.” “Afghanistan is the place where the world saw fit to stash all the tribes it could not handle elsewhere.” Rumsfeld specifically asked for a copy of the Pardo-Maurer document in a snowflake on September 13, 2002, included here as the cover memo.

Document 6

Digital National Security Archive, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit

In the ongoing debates inside the U.S. government about nation-building in Afghanistan, Rumsfeld insisted that more troops were not the answer, and blamed agencies like State and U.S. AID for the lack of progress. They in turn blamed Rumsfeld for not cooperating with their reconstruction plans and not providing security. He wrote President Bush on August 20, 2002, arguing, “the critical problem in Afghanistan is not really a security problem. Rather, the problem that needs to be addressed is the slow progress that is being made on the civil side.” More troops would backfire, “we could run the risk of ending up being as hated as the Soviets were,” and “without successful reconstruction, no amount of added security forces would be enough.” Yet, because of the “perception that does exist” about security problems, Rumsfeld has assigned a brigadier general (and future U.S. ambassador), Karl Eikenberry, to serve as security coordinator on the staff of the Embassy.

Document 7

Digital National Security Archive, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit

By the fall of 2002, the White House focus centered on the buildup to invading Iraq, to the point that President Bush didn’t even know who his latest commander was in Kabul. This Rumsfeld snowflake, likely to a secretary whose name is redacted on privacy grounds (b6), recounts seeing Bush in the Oval Office on October 21, 2002, asking if he wanted to meet with General Franks (head of Central Command) and General McNeill, and noticing that Bush was quite puzzled. “He said, ‘Who is General McNeill?’ I said he is the general in charge of Afghanistan. He said, ‘Well, I don’t need to meet with him.”

Document 8

Digital National Security Archive, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit

This September 2003 memo from the Secretary of Defense to his top intelligence aide, Steve Cambone, laments that nearly two years into the Afghan war, they still don’t know the enemy. “I have no visibility into who the bad guys are in Afghanistan or Iraq. I read all the intel from the community and it sounds as thought [sic] we know a great deal, but in fact, when you push at it, you find out we haven’t got anything that is actionable.”

Document 9

Digital National Security Archive, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit

Three years into the U.S. nation building project, the Combined Forces Command Afghanistan sent Washington one of its regular “Security Updates” with a two-page list of “ANP Horror Stories” on pages 41 and 42. Police training at that point was in the hands of the State Department (or more precisely, its contractors), which took over from an early failed attempt led by the Germans. So the Secretary of Defense makes sure to alert the Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice, about this “serious problem,” claiming that the two pages “were written in as graceful and non-inflammatory a way as is humanly possible.” Illiterate, underequipped, and unprepared, the police force seemingly had gained little from years of training by State Department contractors, perhaps mainly because police pay was so low that they extorted the very people they were supposed to protect. Later in 2005, the U.S. military would take over police training, and still fail to produce a professional force, not least because the whole idea was foreign to rural Afghans, who settled disputes primarily through village elders.

Document 10

Freedom of Information Act request to the State Department

Ronald Neumann arrived in Kabul as the U.S. ambassador in July 2005, with a long history of connection there as the son of a former U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan. He quickly sized up corruption as “a major threat to the country’s future” describing it as a “long tradition [that] grows like Topsy.” Neumann’s cable ascribes the endemic corruption to multiple factors, “privation” in the form of low official salaries, “insecurity” in the form of 35 years of war, “more foreign ‘loot’” especially the billions coming in from the U.S., “exposure to the outside world” of people better off materially, and “universality” in the sense that everyone was doing it. Neumann also acknowledges the reality that the U.S. was working with “some unsavory political figures” out of necessity. Redacted when the cable was declassified in 2011 are the specific names Neumann reported, and the specific actions he was recommending, but the full version released in 2014 revealed that at the top of his list was an untouchable – Afghan President Hamid Karzai’s half-brother, whom the CIA had paid for years, along with a number of provincial governors, most on U.S. covert payrolls as well. The cable also flags the second front in the Bush Afghan war – narcotics – reporting “opium could strangle the legitimate Afghanistan state in its cradle;” yet, rural Afghans relied on poppy production as their only lucrative crop.

Document 11

Freedom of Information Act request to the State Department

In this cable framed as a personal letter to the Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice, U.S. Ambassador Ronald Neumann leads off with an ominous quote from a Taliban leader: "You have all the clocks but we have all the time." Neumann’s plea is for more resources in order to achieve “victory.” He says the U.S. is failing to fund and support fully the activities needed to bolster the Afghan economy, infrastructure, and reconstruction, and that failure is harming the American mission. "We have dared so greatly, and spent so much in blood and money that to try to skimp on what is needed for victory seems to me too risky." The Ambassador notes, "the supplemental decision recommendation to minimize economic assistance and leave out infrastructure plays into the Taliban strategy, not to ours." He warns that Taliban leaders are issuing statements that the U.S. would grow increasingly weary, while they gained momentum.

Document 12

Freedom of Information Act request to the State Department

U.S. Ambassador Ronald Neumann writes Washington again in February 2006 with some prescient warnings. He reports that violence in Afghanistan is on the rise but claims “violence does not indicate a failing policy; on the contrary we need to persevere in what we are doing.” Large unit force-on-force engagements devastated the Taliban in previous years, but “the Taliban now seems to understand the propaganda value of the [suicide] bomb and will use it to maximum advantage.” Ambassador Neumann defends the importance of “our work with the GOA [Government of Afghanistan] to extend and deepen its reach nationwide.” “The Taliban need not be intellectual giants to understand that their long-term strategy depends on keeping the government weak in the provinces.” Neumann says the insurgency is getting stronger largely due to the “four years that the Taliban has had to reorganize and think about their approach in a sanctuary [tribal areas in Pakistan] beyond the reach of either [Kabul or Islamabad].” If this sanctuary is “left unaddressed, it will also lead to the re-emergence of the same strategic threat to the United States that prompted our OEF [Operation Enduring Freedom] intervention over 4 years ago.”

Document 13

Digital National Security Archive, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit

During May 2006, U.S. Central Command asked the eminent retired four-star general, Barry McCaffrey, to visit Afghanistan and Pakistan and make an assessment of the war (as he had done several times in Iraq). Gen. McCaffrey had served as the drug czar under President Clinton, commanded the “left hook” in the first Gulf War that destroyed so much of the Iraqi army, and won multiple medals for valor and for wounds during the Vietnam war, so his views had significant credibility. Here Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld recommends McCaffrey to the chairman of the Joint Chiefs. The McCaffrey document is couched as a report to his department chairs at the U.S. Military Academy (West Point) where he was an adjunct professor. The cover “snowflake” from Rumsfeld catches only a couple of points from McCaffrey: the lack of small arms for Afghan forces, and the recommendation for almost doubling the size of the Afghan army.

The full document presents a fascinating on-the-one-hand and on-the-other-hand story, praising U.S. and allied troops as well as Hamid Karzai while acknowledging rising violence and Taliban regrouping to the level of battalion-size engagements. McCaffrey warns that the Afghan leadership are “collectively terrified that we will tip-toe out of Afghanistan in the coming few years” and do not believe the U.S. is committed “to stay with them for the fifteen years required to create an independent functional nation-state which can survive in this dangerous part of the world.” He recommends almost doubling the size of the Afghan army (whose “courageous” troops “operate like armed mountain goats in the severe terrain”), claiming “[a] well-equipped, multi-ethnic, literate, and trained Afghan National Army is our ticket to be fully out of country in the year 2020.” A different ticket would be punched in 2021, not least because the Army never achieved any of McCaffrey’s four objectives. McCaffrey saw the Afghan police as “disastrous” but could only think of more money plus adding “a thousand jails, a hundred courts, and a dozen prisons.”

McCaffrey provocatively leads his section on Pakistan with this query: “The central question seems to be – are the Pakistanis playing a giant double-cross in which they absorb one billion dollars a year from the U.S. while pretending to support U.S. objectives to create a stable Afghanistan – while in fact actively supporting cross-border operations of the Taliban (that they created) – in order to give themselves a weak rear area threat for their central struggle with the Indians?” He goes on to doubt that Pakistani leader Pervez Musharraf was playing a deliberate double game, yet even phrasing the question in this way was striking, compared to Rumsfeld’s repeated public praise for Musharraf. Only two months later, Rumsfeld’s own civilian adviser, Dr. Marin Strmecki, would give him an even more detailed report entitled “Afghanistan at a Crossroads,” in which Strmecki doesn’t even see it as a question: “Since 2002, the Taliban has enjoyed a sanctuary in Pakistan.”

Document 14

Freedom of Information Act request to the State Department

U.S. Ambassador Ronald Neumann warns Washington in this cable that "we are not winning in Afghanistan; although we are far from losing" (that would take another 14 years). Echoing Gen. McCaffrey’s conclusions (Document 13), Neumann says the primary problem is a lack of political will to provide additional resources to bolster current strategy and to match increasing Taliban offensives. "At the present level of resources we can make incremental progress in some parts of the country, cannot be certain of victory, and could face serious slippage if the desperate popular quest for security continues to generate Afghan support for the Taliban .... Our margin for victory in a complex environment is shrinking, and we need to act now." The Taliban believe they are winning. That perception "scares the hell out of Afghans." "We are too slow." Rapidly increasing certain strategic initiatives such as equipping Afghan forces, taking out the Taliban leadership in Pakistan, and investing heavily in infrastructure can help the Americans regain the upper hand, Neumann declares. "We can still win. We are pursuing the right general policies on governance, security and development. But because we have not adjusted resources to the pace of the increased Taliban offensive and loss of internal Afghan support we face escalating risks today."

Document 15

Declassified by Department of Defense, September 2009

This is the key document behind the Obama “surge” in Afghanistan that produced the highest U.S. troop levels in the whole 20-year war. President Obama’s holdover Secretary of Defense, Robert Gates, had abruptly fired the U.S. commander in Afghanistan, Gen. David McKiernan, after only 11 months, and replaced him with a Special Operations general named Stanley McChrystal, a favorite of Central Command head Gen. David Petraeus, and an acolyte of the Petraeus counterinsurgency approach that had apparently succeeded in Iraq (critics said top Iraqi clerics had simply ordered a truce, for their own reasons). This 66-page assessment had a convoluted public history: written in August 2009, it leaked to the Washington Post in September, likely as part of Pentagon pressure on Obama to approve more troops, and the Pentagon declassified it right away. The McChrystal strategy called for a “properly resourced” counterinsurgency campaign, with at least 40,000 and as many as 60,000 more U.S. troops and massive aid, especially to build up the Afghan army. He wrote, “I believe the short-term fight will be decisive. Failure to gain the initiative and reverse insurgent momentum in the near-term (next 12 months) – while Afghan security capacity matures – risks an outcome where defeating the insurgency is no longer possible.”

McChrystal asked for 60,000 troops, Obama gave him 30,000 but with an 18-month deadline before they would start coming home, and neither the surge nor the deadline ever produced any “maturity” in Afghan security capacity. Testifying to the Senate in December 2009, McChrystal flatly declared “the next eighteen months will likely be decisive and ultimately enable success. In fact, we are going to win.” His 66 pages remain a testament to American military hubris, full of questionable assumptions – that most Afghans saw the Taliban as oppressors and would side with a government installed by foreigners, that most Afghans shared a national identity, and that the Pakistan sanctuaries would not keep the Taliban going indefinitely.

Document 16

The New York Times, Eric Schmitt, “U.S. Envoy’s Cables Show Worries on Afghan Plans,” January 25, 2010

During the Obama debate over whether to surge or not in Afghanistan, some of the strongest criticism of the McChrystal and Pentagon proposals for expanding the military footprint came from inside the government in classified channels – specifically from the former general who had served multiple tours in Afghanistan (Rumsfeld’s first “security coordinator”) and now served as Obama’s ambassador, Karl Eikenberry. This highly classified November 6, 2009, cable, captioned NODIS ARIES, is couched as a personal letter from Eikenberry to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, opposing the proposed troop influx, the vastly increased costs, the concomitant need for yet more civilians, and the resulting increase in Afghan dependency. Eikenberry spells out his reasons: first that Hamid Karzai “is not an adequate strategic partner” – “[h]e and much of his circle are only too happy to see us invest further. They assume we covet their territory for a never-ending war on terror and for military bases to use against surrounding powers.” Second, “we overestimate the ability of Afghan security forces to take over.” Perhaps most important, “[m]ore troops won’t end the insurgency as long as Pakistan sanctuaries remain,” and “Pakistan will remain the single greatest source of Afghan instability.”

Document 17

The New York Times, Eric Schmitt, “U.S. Envoy’s Cables Show Worries on Afghan Plans,” January 25, 2010

This follow-up cable (see Document 16) by Ambassador Eikenberry to Secretary Clinton, for her “eyes only,” may have undercut his earlier strong argument against the proposed troop surge. It’s possible that Clinton may have pushed back, or Eikenberry got word his opposition was unwelcome – her side of the correspondence is still classified. Here, Eikenberry just asks for more time to deliberate, a more wide-ranging process, looking at more options other than military counterinsurgency, and convening a high-level expert panel. He admits that more troops “will yield more security wherever they deploy, for as long as they stay.” But he points to the previous troop increase in 2008-2009, amounting to 30,000 soldiers, and says “overall violence and instability in Afghanistan intensified.” Neither the Afghan army nor government “has demonstrated the will or ability to take over lead security responsibility,” he continues. There is “scant reason to expect that further increases will further advance our strategic purposes; instead, they will dig us in more deeply.” Eikenberry lost this debate, and the Obama-Gates-McChrystal troop surge produced all-time high levels of U.S. troops in Afghanistan.

Document 18

Washington Post, The Afghanistan Papers, Freedom of Information lawsuit against SIGAR

Among the hundreds of “lessons learned” interviews undertaken by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction and obtained by Craig Whitlock of the Washington Post through two Freedom of Information lawsuits, this one stands out for its long view, its self-critical perspective, and its high policy level. Richard Boucher was the longest-serving State Department spokesman in history, starting under Madeline Albright, continuing under Colin Powell and even Condoleezza Rice, before taking over the South Asia portfolio at State from 2006 through 2009. Boucher candidly told the SIGAR interviewers in October 2015, “Did we know what we were doing – I think the answer is no. First we went in to get al-Qaeda, and to get al-Qaeda out of Afghanistan, and even without killing Bin Laden we did that. The Taliban was shooting back at us so we started shooting at them and they became the enemy. Ultimately, we kept expanding the mission.” Boucher confessed, “If there was ever a notion of mission creep it is Afghanistan.” His 12 pages of interview transcript include multiple striking observations worth reading in full, about corruption, about local governance and the lack thereof, about the U.S. military’s can-do attitude and where it leads, about roads not taken. His judgment about Afghanistan comes down to a long view: “The only time this country has worked properly was when it was a floating pool of tribes and warlords presided over by someone who had a certain eminence who was able to centralize them to the extent that they didn’t fight each other too much. I think this idea that we went in with, that this was going to become a state government like a U.S. state or something like that, was just wrong and is what condemned us to fifteen years of war instead of two or three.”

Document 19

SIGAR https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/testimony/SIGAR-20-19-TY.pdf

Congress created the SIGAR office in 2008 to combat waste, fraud, and abuse in the U.S. reconstruction effort in Afghanistan, and this statement marked the 22nd time the incumbent, John Sopko, had testified before Congress. The proximate cause of this hearing was the Washington Post publication in December 2019 of “The Afghanistan Papers” series by Craig Whitlock, based in large part on the Post’s successful lawsuit against SIGAR to obtain copies of the hundreds of “lessons learned” interviews Sopko’s office had done with former policy makers, contractors, and military veterans of Afghanistan. Whitlock also relied on documents the National Security Archive had won through FOIA, notably the Donald Rumsfeld “snowflakes,” and concluded that the U.S. government had systematically misled the public about ostensible progress over nearly two decades in Afghanistan.

Whitlock himself covered this hearing, and his story included even more colorful quotations, apparently from the Q&A period, than can be found in this prepared testimony. For example, “There’s an odor of mendacity throughout the Afghanistan issue … mendacity and hubris.” “The problem is there is a disincentive, really, to tell the truth. We have created an incentive to almost require people to lie.” “When we talk about mendacity, when we talk about lying, it’s not just lying about a particular program. It’s lying by omissions. It turns out that everything that is bad news has been classified for the last few years.” (See Craig Whitlock, “Afghan war plagued by ‘mendacity’ and lies, inspector general tells Congress,” Washington Post, January 15, 2020.)

But the prepared statement is almost as chilling. Sopko told Congress that the system of rotation of U.S. personnel after a year or less in Afghanistan amounted to an “annual lobotomy.” Sopko gave specific examples of fake data and faulty metrics permeating the reconstruction effort: “Unfortunately, many of the claims that State, USAID, and others have made over time simply do not stand up to scrutiny.” Not least, Sopko concluded that “Unchecked corruption in Afghanistan undermined U.S. strategic goals – and we helped to foster that corruption” through “alliances of convenience with warlords” and “flood[ing] a small, weak economy with too much money, too fast.”

Document 20

SIGAR https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/quarterlyreports/2021-07-30qr-section2-security.pdf

This most recent quarterly report from the Special Inspector General provides some noteworthy evidence explaining why Washington would be so surprised by the rapid collapse of Afghan government forces in the two weeks after this was published. The 34-page “security” section leads with the ongoing withdrawal of U.S. and international troops, and the Taliban offensive that “avoided attacking U.S. and Coalition forces.” Maps in the middle of this section (pp. 54-56) show various open-source estimates for Taliban control over Afghani districts, and the report notes that the U.S. military ceased providing any unclassified estimates in 2019. From April to July, apparently, the number of Taliban-controlled districts went from 73 to 221, or more than half the total. Perhaps the most interesting page is page 62, with the sidebar on “the core challenge of properly assessing reconstruction’s effectiveness.” “For years, U.S. taxpayers were told that, although circumstances were difficult, success was achievable.” The document quotes Gen. David Petraeus in 2011, Gen. John Campbell in 2015, Gen. John Nicholson in 2017, and the Pentagon press secretary in 2021 all endorsing the effectiveness of the Afghan security forces. The SIGAR report comments on the $88 billion invested in those forces: “The question of whether that money was well spent will ultimately be answered by the fighting on the ground.”