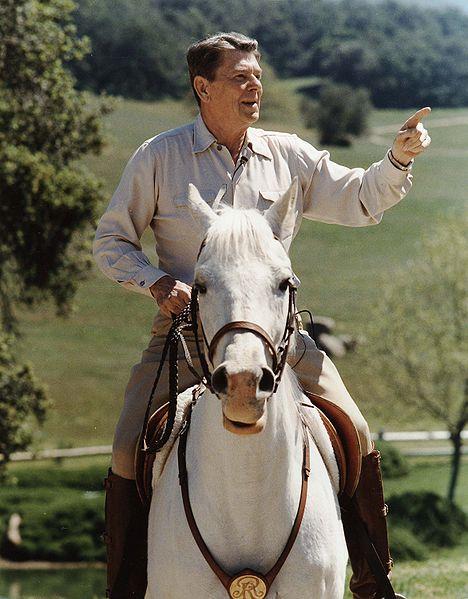

Washington, D.C., August 1, 2024 – The most successful multilateral environmental treaty of all time drew Ronald Reagan’s support despite opposition from his more conservative advisers, because the costs of doing nothing—as analyzed by Reagan’s own economic team—far outweighed the costs to industry of banning the key chemical damaging the ozone layer. The internal White House cost-benefit analysis that helped tip the scales in interagency debates over the 1987 Montreal Protocol on the Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer is among a new set of declassified documents published today by the National Security Archive’s Climate Change Transparency Project.

Despite his zeal for deregulation and conservative business principles, President Reagan understood the gravity of the ozone problem and the environmental ramifications for the planet, according to the newly published records. At the urging of the State Department and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Reagan overruled Cabinet opposition within the Domestic Policy Council to ensure adoption of the final set of U.S. objectives for the treaty. Reagan’s Secretary of State, George P. Shultz, played an especially important role in blocking efforts by the Department of the Interior, the U.S. Trade Representative, and the Office of Management and Budget to subvert or weaken the ozone treaty.

The documents in this Electronic Briefing Book were obtained by the Archive under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), published in the State Department’s Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS) series, or discovered during archival expeditions to the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. Together, these records fill a critical gap in the history of Reagan’s assertive stance on international environmental issues, which was detailed in an earlier Electronic Briefing Book on “U.S. Climate Change Policy in the 1980s.” Among other things, they reveal the previously underreported influence of the Council of Economic Advisers in swaying cabinet negotiations and Reagan’s personal involvement in the treaty negotiations via handwritten guidance.

A Multilateral Success

Nearly four decades ago, a May 1985 Nature report published the alarming finding that a massive hole had opened in the ozone shield and that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were to blame for the breakdown. Nine months after formal diplomatic negotiations on the issue began in December 1986, dozens of nations met in Montreal in September 1987 to sign an agreement that would significantly reduce CFCs in the atmosphere. In his statement on the signing of the treaty, Reagan called the Montreal Protocol a “model of cooperation” and “an extraordinary process of scientific study, negotiations among representatives of the business and environmental communities, and international diplomacy.”[1] The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone layer officially entered into force on January 1, 1989.

Since the implementation of the Protocol, the EPA has estimated that Americans born between 1890 and 2100 have avoided approximately 2.3 million skin cancer deaths.[2] More recently, an October 2022 scientific assessment sponsored by the United Nations (UN), the European Commission and U.S. federal agencies reported that not only is the ozone layer on track to recover within decades but that the global phaseout of ozone-depleting chemicals is also benefiting efforts to mitigate climate change.[3] In June, a Nature Climate study found that levels of the harmful ozone-depleting hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) have fallen faster than expected—a result attributed to “the efficacy of the Montreal protocol.”[4]

As the only UN treaty ratified by every country on the planet, the Montreal Protocol is a powerful and successful example of environmental multilateralism, and a re-examination of the circumstances of its negotiations provides a useful framework for studying the state of international environmental negotiations at present. As the authors of the treaty said, the Montreal Protocol demonstrated “that nations are capable of undertaking complicated cooperative actions in the real world of ambiguity and imperfect knowledge.”[5]

Standing in sharp contrast to today’s partisan gridlock over a comprehensive climate policy, the Montreal Protocol has been a “true champion for the environment over the last 35 years,” according to Meg Seki, Executive Secretary of the United Nations Environment Program’s Ozone Secretariat.[6]

Conservatives have not always stood in “lock-stop opposition” to the climate and environment agenda, however,[7] and the declassified records featured here show that even conservative stalwarts like President Reagan appreciated the need to address global environmental challenges, in particular those related to human-driven degradation of the atmosphere.[8] Despite its overall ideological adherence to small government and free market economics, the Reagan administration demonstrated significant U.S. leadership in tackling the risks posed by the production and use of ozone-depleting chemicals.

The Backstage Debates

The lead U.S. negotiator to the Protocol, Richard Elliot Benedick, later wrote a comprehensive history of the treaty negotiations that is critical for understanding the underlying scientific issues involved as well as the complex domestic politics and international diplomacy surrounding the talks.[9] In both in his book and in a subsequent oral history interview[10], Benedick, who recently passed away at age 88, argued that U.S. leadership was vital to the successful negotiation of a strong ozone treaty with a clear and firm timetable for reducing the production of CFCs.[11]

The declassified record demonstrates, however, that there were strong disagreements within the Reagan administration over the treaty negotiations and that 1986 and 1987 were marked by intensive interagency debates over the U.S. position on the ozone treaty. Throughout these deliberations, State Department and EPA representatives working on the issue reported to a special senior-level working group of the White House Domestic Policy Council chaired by Attorney General Ed Meese. The rationale behind DPC’s major involvement in formulating the U.S. ozone policy was that the negotiation of an environmental treaty on CFCs and similar chemicals would require domestic implementing regulations. But while the DPC was responsible for the preparation of the options paper for the President, State took the lead in formulating arguments in defense of a strong and effective U.S. negotiating position.

The DPC was co-chaired by Interior Secretary Donald Hodel, who, along with representatives from the departments of Commerce, Agriculture, the Office of Management and Budget, the Office of Science and Technology Policy, and parts of the White House Staff, had “serious doubts” that State Department and EPA leadership on the matter was either “good politics or good policy.” (Document 1) In early 1987, these treaty skeptics began to “reopen basic questions about the scientific evidence and the possible damage to the U.S. economy from imposing additional CFC controls,” despite volumes of data and scientific analysis being generated by the EPA, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

In addition to undermining the basic science surrounding the damage to the ozone layer, Hodel’s antiregulatory coalition opposed key provisions in the proposal, specifically a second-stage reduction of about 30 percent in CFCs (to make the total cutback 50 percent). EPA and State argued that a “20 percent protocol” would be a “weak protocol” and in some ways “worse than no treaty at all because it would convey a false sense of having taken sufficient action.” But the other U.S. agencies, along with the European Commission, Japan, and the Soviet Union, staunchly opposed the second phase.[12]

Meanwhile, the State Department was concerned that a dysfunctional DPC would result in an about-face by the U.S. regarding the goals it had pressed for in the negotiation, therefore risking “the embarrassing loss of international credibility, as well as domestic political backlash” and “unilateral U.S. controls.” (Document 3) The last point was driven by the likelihood that, if an international agreement was not reached, the courts would compel EPA to impose unilateral reductions, which would hurt U.S industry. To head off the rear-guard effort by Hodel and his coalition, Secretary of State George P. Shultz wrote to Attorney General Meese laying out the serious repercussions of such a reversal. He proposed the issue be taken “to the President without further delay.” (Document 3) Meese pushed back on Shultz, however, in favor of “airing [the] views from all interested officers in the President’s Cabinet.” (Document 4)

Cancer Deaths Outweigh Economic Cost

A “major break” in the interagency debates came in May 1987 when the President’s Council of Economic Advisers produced a cost-benefit analysis of the CFC control option, which the National Security Archive is publishing here for the first time. (Document 2)[13] The study concluded, despite any scientific or economic uncertainties, that the financial benefits of avoiding future deaths and skin cancer “far outweighed” the cost of CFC controls as estimated by industry and even the EPA. Furthermore, the cost-benefit analysis concluded that the “additional 30% reduction in CFCs also appears to be economically justified on the basis of current knowledge.” The CEA, which was “initially skeptical of the wisdom of regulation to protect the stratospheric ozone layer” (as the DPC noted in its talking points that summer) (Document 5), ultimately helped to sway administration officials who were watching the controversy unfold and overcome Hodel’s rear-guard efforts.[14]

With the federal agencies still in disarray throughout the summer of 1987, Benedick said it had become clear that President Reagan would ultimately have to decide on the provisions of the treaty. On June 18, 1987, the morning of a “crucial DPC meeting” with the President,[15] Reagan wrote the following entry in his daily diary:

"Then a meeting of the Domestic Council. I'm faced with making a decision on instructions to our team on what we seek world wide in reduction of FluoroCarbons that are destroying the Ozone layer. Right now I don’t have the answers."[16]

What happened during the period between the June 18 meeting, when Reagan did not “have the answers,” and his June 24 sign-off on all the State Department positions, overruling the dissenting Cabinet members, remains something of a mystery. Benedick credited the change to “the personal and behind-the-scenes interventions” of Shultz, who was “decisive in preventing dramatic reversal of U.S. policy.”[17] The cost-benefit analysis from Reagan’s economic advisers must have also played a major role. Finally, conservative forces within the Reagan administration—and even Reagan’s own popularity—were at a low ebb at that moment in June 1987, with daily congressional hearings on the Iran-Contra scandal dominating the front pages and television news.

With Reagan’s decisions finalized on June 26 (Documents 7 and 8), the State Department had won every policy battle—a fact reflected in the DPC options paper, which shows Reagan’s handwritten initials next to every State- and EPA-supported option (Document 6). The White House, led by Chief of Staff Howard Baker, was certainly aware of the skeptical views held by members of the Cabinet and for reasons of confidentiality wanted no part of this internal debate leaked to the press. Talking points for Baker’s call to Deputy Secretary of State John Whitehead recommended that the Chief of Staff push State Department negotiators to ensure that treaty participation was “well above the 50%” of countries involved that State Department “negotiators have in their heads now.” (Document 9)

In a decision that “was deliberately not publicized”[18]—presumably due to the President’s small government ideology, or, as Benedick suggested, to spare Hodel’s coalition from further embarrassment—Reagan overruled the dissenting Cabinet members to approve the U.S. goals for the treaty.[19] The President’s centrality in cabinet negotiations would “allow the United States to play a leadership role in dealing with this problem,” according to Whitehead’s letter of July 16, 1987, adding that the international agreement would be “a major victory” for Reagan. (Document 10) Following the adoption of the Montreal Protocol on September 16, 1987, which largely conformed to U.S. objectives, Reagan submitted the treaty to Congress for ratification in April 1988.

On September 18, 1987, two days after the adoption of the protocol, Reagan wrote the following in his daily diary:

"Then at 10 A.M. Lee Thomas came in to brief me on agreement we have negotiated with 23 Nations to reduce carbo flurocarbons—in our effort to stop reducing the Ozone layer. This is an historic agreement."[20]

“Best Accidental Climate Treaty”

Today, the Montreal Protocol is hailed as the most successful environmental treaty to date, but it also deserves recognition as the “Best Accidental Climate Treaty.”[21] By phasing out the production of CFCs and other ozone-depleting substances, the Montreal Protocol prevented between 0.5 and 1 degree Celsius of global warming by 2100, according to NOAA.[22] Additionally, the success of the 2016 Kigali Amendment to the treaty—in which countries agreed to gradually phase out hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), another greenhouse gas pollutant—bolsters the Montreal Protocol’s standing as a successful, flexible environmental treaty that continues to incorporate and consider changing climate science and solutions.

While climate scholars and practitioners agree that negotiations needed to address climate change are exceedingly more complex than protecting the ozone layer, the protocol’s achievements hold valuable lessons for present and future climate negotiations. As Benedick wrote in his final chapter of Ozone Diplomacy, the multilateral and domestic negotiations that led to the successful enactment of the Montreal Protocol suggest several elements of a “new kind of diplomacy” for addressing global ecological threats like climate change, including the centrality of science in the negotiations; the willingness of governmental action despite a level of scientific uncertainty; a well-informed public; and multilateral diplomacy between countries.[23]

The Documents

Document 1

Ronald Reagan Library, Robert Johnson Files, Stratospheric Ozone (2)

Paul Gigot, a White House Fellow and Wall Street Journal editorial writer serving on the Domestic Policy Council, gives his assessment of “the ozone issue” to Patricia Hines, the Chief of Staff to Reagan’s Assistant for Domestic Policy. Gigot sends the memo several days before the next round of Ozone Layer Protocol Negotiations, which will be held in Vienna, Austria, from February 23-27. At this stage in treaty negotiations, Gigot has “serious doubts” about the State Department’s and the EPA’s leadership in the policy process, specifically their call for a 95% phase-down in CFCs. Written several days after a DPC working group meeting, Gigot characterizes the Department of Justice and Department of the Interior working group representatives as the “sober voices” of the policy process. However, this memo illustrates the rear guard’s tactic of calling the science into question during late-stage negotiations when Gigot asks “whether the Administration has ever decided that the science linking CFCs with ozone depletion justifies a phase-down.” In an attempt to convince the administration to opt for a freeze of CFC production rather than a 95% phase-down, Gigot also speculates on the cost-benefit analysis of CFC regulation. According to his assessment, the administration was backed into a corner: either “penalize our own industry,” or the Reagan administration will find “itself in the unusual position of being allied with Germany’s Green Party!” Gigot would go on to lead the conservative and anti-regulatory editorial pages of the Journal.

A transcript of the memo can be found in the State Department’s Foreign Relations of the United States, 1981-1988, Volume XLI, Global Issues II, Document 357, an extremely useful guide to the documentary record on the Montreal decisions.

Document 2

Ronald Reagan Library, Beryl Sprinkel Files, Domestic Policy Meeting Re: Stratospheric Ozone, Box 11

At the height of interagency treaty negotiations during the spring of 1987, a “major break” in the debates came when the Council of Economic Advisers conducted a cost-benefit analysis on the current CFC control options being discussed. In a memorandum for Ralph Bledsoe, Director of the Domestic Policy Council, Thomas Moore, one of three members of the CEA, presses Bledsoe to include this analysis in a background paper to be presented at an upcoming DPC meeting. The analysis assesses a freeze and 20% cutback in CFCs, “which will avoid approximately 992,900 deaths in the U.S.,” and an additional 30% reduction, which “will save an additional 78,700 lives.” The CEA’s assessment of the benefits, which, importantly, “do not even include non-health benefits or benefits from avoidance of non-fatal skin cancers and cataracts,” are even larger than the cost-benefit scenarios generated by the EPA or industry groups up to that point. The memo concludes that “the benefit-cost ratio of the freeze +automatic 20% reduction is approximately 100 to 1,” and an additional 30% reduction “also appears to be economically justified.” According to Benedick’s account in Ozone Diplomacy (page 63), the CEA cost-benefit analysis “dismayed the revisionists and helped sway some administration officials who had been watching the controversy from the sidelines.”

Document 3

Department of State FOIA

The State Department’s ongoing struggle within President Reagan’s Cabinet with opponents of the proposed ozone protocol is the focus of the letter from Secretary of State Shultz to Chair of the DPC Meese. A previous DPC meeting on the topic on May 20 had failed to resolve these deep divisions, and Secretary Shultz—at the urging of Assistant Secretary of State John Negroponte—writes Attorney General Meese to press the urgent need to sustain U.S. support of the ozone agreement. Shultz expresses his concern over a dysfunctional DPC and warns against any “backsliding” among agencies at the DPC that could “reopen the entire international negotiation” by casting doubt on the science. Attached to Shultz’s letter is the Protocol Summary, which he strongly suggests should be taken “to the President without further delay” if they don’t want to “jeopardize the progress we have made in this major international negotiation.”

Document 4

Ronald Reagan Library, Nancy Risque Files, Cabinet Secretary Series II, Stratospheric Ozone (1), Box 23

The day after Shultz sent his letter advocating against a reversal in U.S. policy and in favor of decisive action on the President’s part to move ozone negotiations forward, Meese pushes back. While he can “appreciate” the State Department and the Environmental Protection Agency’s roles in negotiating towards a strong treaty, he seems to advocate for the members of the DPC who questioned the scientific theories, the health and environment assessment, and the cost-benefit analysis: Hodel’s camp. Meese also tries to assuage Shultz’s concerns by informing him that EPA Administrator Lee Thomas is now a member of the DPC and “his views will continue to be fully considered.” While Benedick’s account of U.S. negotiations in Ozone Diplomacy does not elaborate in great detail on Meese’s influence during the process, the documents show that, despite a split DPC, Meese was perhaps not-so-secretly on Hodel’s side during cabinet debates.

Document 5

Ronald Reagan Library, Beryl Sprinkel Files, Domestic Policy Council Meeting Re: Stratospheric Ozone, Box 11

In preparation for what would be a crucial June 18 meeting with President Reagan, the Domestic Policy Council’s talking points begin with a summary of CEA’s shifting position on CFC regulation. “Initially skeptical of the wisdom of regulation to protection the stratospheric ozone layer … CEA has reached its position in support of a strong international protocol only after careful examination of the best data currently available.” These talking points complement CEA’s cost-benefit analysis (Document 4) and summarize the substantial findings: “the health and environmental risks of inaction and indecision are substantial.” At the June 18 meeting, EPA Administrator Lee Thomas and Deputy Secretary of State John Whitehead defended a strong protocol, with Whitehead even sending a follow-up letter to Chief of Staff Howard Baker reiterating his argument and concisely annotating every option now on the President’s desk. Afterwards, Reagan overruled the antiregulatory forces within the interagency debates, and, “to the surprise even of insiders,” accepted the critical provision for an automatic 30 percent second-stage reduction. The CEA’s case for a follow-up 30 percent reduction played a major role in bolstering the State Department and EPA’s position. In the last line of the talking points, the DPC writes that a successful Montreal Protocol, led by the U.S., “would be a major diplomatic and domestic success.”

Document 6

Ronald Reagan Library, Nancy Risque Files, Cabinet Secretary Series II, Stratospheric Ozone (5), Box 23

The June 18, 1987, Domestic Policy Council meeting with President Reagan marked an inflection point in the interagency debates, with EPA Administrator Lee Thomas and Deputy Secretary of State John Whitehead defending a strong protocol. Bledsoe’s memorandum requesting the President’s guidance ahead of the next round of negotiations on June 29 provides a meticulous outline of the interagency debates at play. According to a note at the top of the memo, Reagan saw the memo on June 24, five days before the negotiations, and marked his initials under every provision supported by both the State Department and Environmental Protection Agency and denies every option supported by the Department of the Interior. In Benedick’s account, Whitehead (acting for Shultz) followed up with a letter that evening to White House Chief of Staff Howard Baker concisely summarizing the State Department’s position, which Benedick believes had a notable impact on Reagan’s decision to overrule the Hodel’s antiregulatory coalition. The transcript of the memo was first published on the State Department’s Foreign Relations of the United States, 1981-1988, Volume XLI, Global Issues II (Document 371).

Document 7

Ronald Reagan Library, Nancy Risque Files, Cabinet Secretary Series II, Stratospheric Ozone (7), Box 23

After Reagan signed off in favor of all State Department-recommended provisions (Document 6), his staff prepared a two-page classified decision memo (Document 8) and cover letter sent by Cabinet Secretary Nancy Risque to the President. In her cover letter, Risque recaps the June 18 DPC meeting and Reagan’s ultimate decision to “reaffirm strong measures for protecting the ozone layer.” She attaches the classified memo for his review, noting that a statement has been added to emphasize the importance of “maximum [treaty] participation by other countries.” The marking at the top of this document indicates that Reagan saw the memo on June 24, and he marked his initials next to the word “Approve.”

Document 8

Ronald Reagan Library, Nancy Risque Files, Cabinet Secretary Series II, Stratospheric Ozone Protocol (1), Box 23

This two-page memorandum expresses Reagan’s formal instructions to the DPC and U.S. delegation ahead of the next round of international treaty negotiations. Reagan supports the following U.S. position: a freeze to 1986 levels on CFCs and halons; strong monitoring, reporting, and enforcement measures; an immediate 20% reduction from 1986 levels of CFCs, and a second-phase 30% reduction eight years after the treaty enters force; and a trade provision that will restrict against CFC-related imports from non-compliant countries. The U.S. position also supports a flexible treaty that can be adapted “based on regularly scheduled scientific assessments.” In a consideration of today’s debates over appropriate developed vs. developing country participation in emissions reductions, Reagan also recommends that developing countries be given a “grace period” until 2000 to “allow some increases in their domestic assumption,” while “due weight” should be given “to the significant producing and consuming” developed countries. However, as emphasized in Risque’s cover letter, Reagan signs off on the provision that the protocol will only enter into force when a majority of major producing and consuming countries have signed and ratified the treaty.

Document 9

Ronald Reagan Library, Nancy Risque Files, Cabinet Secretary Series II, Stratospheric Ozone (7), Box 23

In this staff memo to White House Chief of Staff Howard Baker (formerly Senate Majority Leader, R-TN) ahead of his phone call with Deputy Secretary of State John Whitehead (the number two State negotiator behind Shultz), it is recommended that Baker emphasize confidentiality ahead of and during the upcoming June 29 negotiations in Montreal and that he direct the negotiating team to communicate back the results of the negotiations through classified channels. White House staff, aware of the skeptical views from Hodel’s camp, wanted no internal debate leaked after Reagan signed off on the U.S. position that very same day. The memo also recommends that Baker push the State Department to “do their damdest to get maximum participation” from top CFC producing and consuming countries and “well above the 50% ... [that State] negotiators have in their heads now.”

Document 10

Ronald Reagan Library, Nancy Risque Files, Cabinet Secretary Series II, Stratospheric Ozone (4), Box 23

This last letter from Whitehead to Baker, written in the weeks following the latest round of treaty negotiations held from June 29-30, gives an update of country positions on the ozone protocol. Canada, Norway and New Zealand have each provided open endorsements for the U.S. position, while Belgium and Denmark gave “behind-the-scenes support.” However, the European Commission’s stance encouraged Japan and the Soviet Union to “resist significant reductions” in CFCs. Although some countries questioned the proposal to give weight to significant producing and consuming countries, Whitehead confirms that the U.S. is “in a good position as we approach the September Diplomatic Conference.” According to Whitehead, the President’s support for the treaty objectives has allowed “the United States to play a leadership role in dealing with this problem.”

Notes

[1] , Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum, Statement on the Signing of the Montreal Protocol on Ozone-Depleting Substances, April 5, 1988.

[2] The Department of State, The Office of Environmental Quality, The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer.

[3] World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Executive Summary. Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2022, GAW Report No. 278, 56 pp.; WMO: Geneva, 2022.

[4] Agence France-Presse, The Guardian, “Harmful gases destroying ozone layer falling faster than expected, study finds,” June 11, 2024.

[5] Benedick, Richard Elliot, “Ozone Diplomacy,” Issues in Science and Technology, Fall 1989, Vol 6. No. 1, pg 45, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43309418

[6] World Meteorological Organization, “Ozone layer recovery i son track, helping avoid global warming by 0.5 degrees C,” January 9, 2023.

[7] Dr. Robert Wampler, “U.S. Climate Change Policy in the 1980s,” National Security Archive, December 2, 2015.

[8] Reagan underwent removal of two skin cancers in 1985 and 1987, and some scholars speculate that this had something to do with his interest in the ozone treaty.

[9] Richard Elliot Benedick, Ozone Diplomacy: New Directions in Safeguarding the Planet, 1991.

[10] The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, Foreign Affairs Project, “Richard Elliot Benedick,” Interviewed by Raymond Ewing, August 31, 1999.

[11] Trip Gabriel, “Richard Benedick, Negotiator of Landmark Ozone Treaty, Dies at 88,” The New York Times, April 7, 2024.

[12] Richard Benedick, Ozone Diplomacy, page 65.

[13] Benedick, page 63.

[14] Benedick, page 63.

[15] Benedick, page 66.

[16] Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute, White House Diaries, Diary Entry – June 18, 1987: https://www.reaganfoundation.org/ronald-reagan/white-house-diaries/diary-entry-06181987/

[17] Richard Benedick, Ozone Diplomacy, 65.

[18] Benedick, page 67.

[19] Benedick discusses the internal Cabinet debate and Reagan’s final decision in Chapter 5: Forging the U.S. position, pages 51-67. He also discuses these debates in his oral history interview with Ewing.

[20] Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute, White House Diaries, Diary Entry – September 18, 1987: https://www.reaganfoundation.org/ronald-reagan/white-house-diaries/diary-entry-09181987/

[21] Jenessa Duncombe, “How the ‘Best Accidental Climate Treaty’ Stopped Runaway Climate Change,” Eos Science News, September 2, 2021.

[22] National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “Montreal Protocol emerges as a powerful climate treaty,” January 11, 2023.

[23] Richard Benedick, Ozone Diplomacy, Chapter 19: A New Global Diplomacy: Ozone Lessons and Climate Change, pages 306-334.