The Cuban Missile Crisis @ 60

Washington, D.C., December 13, 2022 - In the immediate aftermath of the resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev met with the Czechoslovakian Communist Party leader, Antonín Novotný, and told him that “this time we really were on the verge of war,” according to minutes of their October 30, 1962, meeting posted today by the National Security Archive. “We were truly on the verge of war,” Khrushchev repeated later in the meeting, during which he explained how and why the Kremlin “had to act very quickly” to resolve the crisis as the U.S. threatened to invade Cuba. “How should one assess the result of these six days that shook the world?” he pointedly asked, referring to the period between October 22, when President Kennedy announced the discovery of the missiles in Cuba, and October 28, when Khrushchev announced their withdrawal. “Who won?” he wondered.

To “assess the result” and the implications of those dangerous days when the world stared down what Kennedy aide Theodore Sorensen called “the gun barrel of nuclear war,” the National Security Archive is posting a final collection of postmortem documents, concluding its series on the 60th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis. In addition to the summary of the Khrushchev-Novotný meeting, the selection includes correspondence from Khrushchev to Castro, Castro’s own lengthy reflections on the missile crisis, a perceptive aftermath report from the British Ambassador to Havana, and a lengthy analysis by the U.S. Defense Department on “Some Lessons from Cuba.”

The missile crisis abated on October 28, 1962, when Nikita Khrushchev announced he was ordering a withdrawal of the just-installed nuclear missiles in Cuba in return for a U.S. guarantee not to invade Cuba. His decision came only hours after a secret meeting between Robert Kennedy and Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin during which the two agreed to swap U.S. missiles in Turkey for the Soviet missiles in Cuba—a part of the resolution of the crisis that remained secret for almost three decades.

But the crisis did not actually conclude. Cut out of the deal to resolve the crisis, a furious Fidel Castro issued his own “five point” demands to end the crisis and refused to allow UN inspectors on the island to monitor the dismantling of the missiles unless the Kennedy administration allowed UN inspectors to monitor dismantling of the violent exile training bases in the United States. In addition to the missiles, the United States demanded that the USSR repatriate the IL-28 bombers it had brought to Cuba, which the Soviets had already promised Castro they would leave behind.

The Soviets had also promised to turn over the nearly 100 tactical nuclear weapons they had secretly brought to the island—a commitment that Khrushchev’s special envoy to Havana, Anastas Mikoyan, determined was a dangerous mistake that should be reversed. In November 1962 “the Soviets realized that they faced their own ‘Cuban’ missile crisis,” observed Svetlana Savranskaya, co-author, with Sergo Mikoyan, of The Soviet Cuban Missile Crisis: Castro, Mikoyan, Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Missiles of November. “The Soviets sent Anastas Mikoyan to Cuba with an almost impossible mission: persuade Castro to give up the weapons, allow inspections and, above all, keep Cuba as an ally,” she noted. “Nobody knew that Cuba almost became a nuclear power in 1962.”

From the Cuban perspective, the outcome of the Crisis de Octubre was the worst of all worlds: a victory for the enemy and a betrayal by the ally that had installed the missiles to defend Cuba. Instead of relief that a massive U.S. invasion had been avoided, along with nuclear war, the Cubans felt “a great indignation” and “the humiliation” of being treated as “some type of game token,” as Castro recounted at a conference in Havana 30 years later. But in his long report to London, drafted only two weeks after the Soviets began dismantling the missiles, British Ambassador Herbert Marchant perceptively noted that it was “better to be humiliated than to be wiped out.”

At the time, Ambassador Marchant presciently predicted “a sequence of events” from which the Cuban revolution would emerge empowered and stronger from the crisis: “A U.S. guarantee not to invade seems certain; a Soviet promise to increase aid seems likely; a Soviet plan to underwrite Cuba economically and build it into a Caribbean show-piece instead of a military base is a possibility,” he notes. “In these circumstances, it is difficult to foresee what forces would unseat the present regime.” His prediction would soon be validated by Khrushchev’s January 31, 1963, letter inviting Castro to come to the Soviet Union for May Day and to discuss Soviet assistance that would help develop his country into what Khrushchev called “a brilliant star” that “attracts the working class, the peasants, the working intellectuals of Latin American, African and Asian countries.”

In his conversation with Novotný, the Soviet premier declared victory. “I am of the opinion that we won,” he said. “We achieved our objective—we wrenched the promise out of the Americans that they would not attack Cuba” and showed the U.S. that the Soviets had missiles “as strong as theirs.” The Soviet Union had also learned lessons, he added. “Imperialism, as can be seen, is no paper tiger; it is a tiger that can give you a nice bite in the backside.” Both sides had made concessions, he admitted, in an oblique reference to the missile swap. “It was one concession after another … But this mutual concession brought us victory.”

In their postmortems on the missile crisis, the U.S. national security agencies arrived at the opposite conclusions: the U.S. had relied on an “integrated use of national power” to force the Soviets to back down. Since knowledge of the missile swap agreement was held to just a few White House aides, the lessons learned from the crisis were evaluated on significantly incomplete information, leading to flawed perceptions of the misjudgments, miscalculations, miscommunications, and mistakes that took world to the brink of Armageddon. The Pentagon’s initial study on “Lessons from Cuba” was based on the premise that the Soviet Union’s intent was first and foremost “to display to the world, and especially our allies, that the U.S. is too indecisive or too terrified of war to respond effectively to major Soviet provocation.” The decisive, forceful, U.S. response threatening “serious military action” against Cuba was responsible for the successful outcome. For the powers that be in the United States, that conclusion became the leading lesson of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

But none of the contemporaneous evaluations of the crisis, whether U.S., Soviet or Cuban, attempted to address what is perhaps the ultimate lesson of the events of 1962—the existential threat of nuclear weapons as a military and political tool. In his famous missile crisis memoir, Thirteen Days, published posthumously after his assassination, Robert Kennedy posed a “basic ethical question: What, if any, circumstances or justification gives this government or any government the moral right to bring its people and possibly all peoples under the shadow of nuclear destruction?” Sixty years later, as the world still faces the threat of the use of nuclear weapons, that question remains to be answered.

The Documents

Document 1

Central State Archive, Archive of the CC CPCz, (Prague): File: “Antonin Novotny, Kuba,” Box 193.

Two days after Nikita Khrushchev announced the withdrawal of the nuclear missiles from Cuba, he and top Soviet officials met with the head of the Czechoslovakian Communist Party, Antonín Novotný at the Kremlin. Khrushchev uses the opportunity to provide one of his first significant accounts of the crisis, as well as his initial assessment of its outcome and meaning. “This time we really were on the verge of war,” he tells Novotný toward the beginning of the meeting, and again at the end, making it imperative that “we had to act fast” to avoid a nuclear conflict. Khrushchev describes how U.S. military maneuvers—“the codeword was ‘Ortsac’, which is Castro spelled backwards,” Khrushchev explained—were preparations for a massive U.S. invasion. Fidel Castro had written him a letter stating that the invasion was coming within 24 hours and that the Soviets should fire their nuclear missiles if the U.S. attacked Cuba. “We were completely aghast,” Khrushchev comments, recounting his reaction. “After all, if a war started, it would primarily be Cuba that would vanish from the face of the earth.” “After all, millions of people would die, in our country too. Can we even contemplate such a thing?”

Khrushchev misleads Novotný about how the crisis was actually resolved, telling him that he had withdrawn the Soviet demand to swap the U.S. missiles in Turkey for the Soviet missiles in Cuba and settled for a U.S. commitment not to invade Cuba. But the Soviet leader believes that the Communist bloc had emerged victorious from the conflict. “I am of the opinion that we won,” he says. “We achieved our objective—we wrenched the promise out of the Americans that they would not attack Cuba” and showed the U.S. that the Soviets had missiles “as strong as theirs.” “Now they have felt the winds of war in their own house,” he says. But the Soviet bloc had also learned lessons, according to Khrushchev. “Imperialism, as can be seen, is no paper tiger; it is a tiger that can give you a nice bite in the backside.”

“One of the most important consequences of the whole conflict and our approach,” Khrushchev tells Novotný, “is the fact that the whole world now sees us as the ones who saved peace. I now appear to the world as a lamb,” according to the Soviet leader who had instigated the crisis by attempting to surreptitiously install the missiles in Cuba. “That is not bad either.”

Document 2

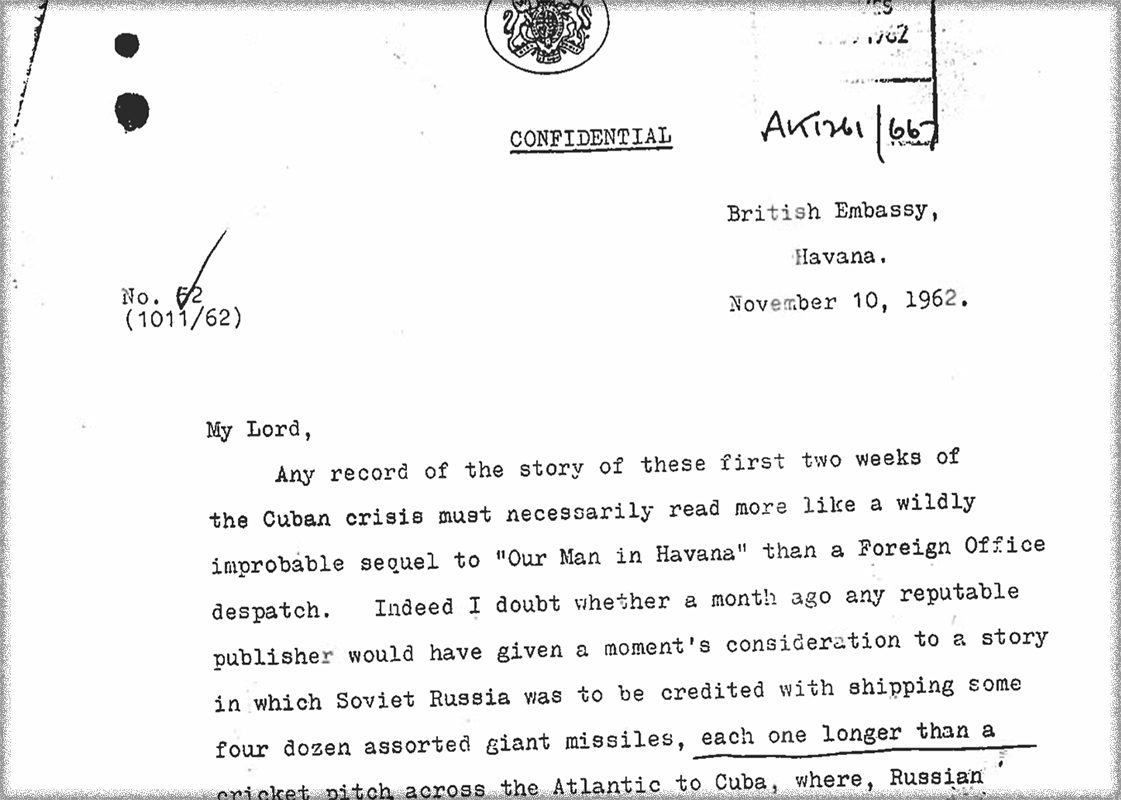

British Foreign Office Archives

With the drama of the aftermath of the missile crisis still playing out in Cuba, British Ambassador Herbert Marchant sent a lengthy, and literary, cable to London evaluating the fallout and the ongoing diplomatic efforts by the Soviets and the United Nations to address Fidel Castro’s “five points” for ending the crisis on Cuban terms. The cable also addresses the impact on Castro and the Cuban people of being used, and pushed aside, by their ally, the Soviet Union, in Khrushchev’s decision to withdraw the missiles without consulting the Cubans. “To discover in the early stages of an 18 round contest that you are not even one of the contestants but only the prize money is not an easily forgotten experience for a sensitive young nation,” Marchant observes. “But better to be humiliated than to be wiped out,” he cogently suggests. In his report, Marchant presciently predicts “a sequence of events” in the aftermath of the crisis “which could be highly satisfactory to the present regime. A U.S. guarantee not to invade seems certain; a Soviet promise to increase aid seems likely; a Soviet plan to underwrite Cuba economically and build it into a Caribbean show-piece instead of a military base is a possibility,” he notes. “In these circumstances, it is difficult to foresee what forces would unseat the present regime.”

Document 3

Declassified and provided by Fidel Castro to the National Security Archive; translated by Dr. Svetlana Savranskaya and originally published in the National Security Archive documents reader, The Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962, by Laurence Chang and Peter Kornbluh

As part of a 30th anniversary conference on the missile crisis in Havana, organized in January 1992 by Brown University professor James G. Blight with support from the National Security Archive, Fidel Castro declassified several documents relating to the missile crisis, including this long letter to him from Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev written several months after the crisis ended. The letter contains an invitation for Castro to come to Moscow and talk to Khrushchev about the future of Soviet-Cuban relations. In an effort to address “a certain amount of resentment” about the indignities suffered by the Cuban leader and his country as a result of the missile crisis having been resolved without their participation, Khrushchev shares his motivations for installing the missiles to defend the Cuban revolution from the U.S. “imperialists” and says he withdrew them to avoid a U.S. invasion of Cuba that, in the Soviet estimate, would have defeated Castro’s forces and the Soviet personnel fighting alongside them. From that decision, he argues, “there are reasons to believe that you have won a truce and that you will take advantage of it for peaceful construction,” with full Soviet support. “And we, comrade Fidel, are ready to cooperate with you,” Khrushchev offers. “The Soviet Union is doing, and will do, everything possible to develop this cooperation” toward the goal of creating a prosperous, revolutionary “beacon” that “attracts the working class, the peasants, and the working intellectuals of Latin American, African, and Asian countries.” If Castro agrees to come for May Day events in Russia, Khrushchev offers to take him hunting and fishing to enjoy the outdoors and “the poetry of the landscape.”

Document 4

Foreign Broadcast Information Service

At the 30th anniversary conference in Havana, on January 11, 1992, Fidel Castro spent several hours recounting his experience during and after the missile crisis—providing his own postmortem as the last surviving leader of that historic and dangerous conflict. The CIA’s Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS), which collected and translated foreign broadcasts, published an English version of his remarks after they were aired on Cuban television. He reflected on what he called Kennedy’s “courage” to resist the pressures from his military to attack Cuba and acknowledged that hundreds of thousands of lives would have been lost if the U.S. had invaded. He also recalled the bitter sense of betrayal when Khrushchev announced the withdrawal of the missiles without consulting him. Instead of relief that the threat of an imminent U.S. invasion and nuclear war had receded, the Cubans, Castro stated, felt “a great indignation because we realized we had become some type of game token.”

At the time, Castro did not know of the secret Kennedy-Khrushchev deal to resolve the crisis by swapping U.S. missiles in Turkey for the Soviet missiles in Cuba. He recounted when, during his trip to Moscow in the spring of 1963, Khrushchev inadvertently read him a document that revealed the secret swap, confirming Fidel’s belief that Cuba had been “used as an exchange token.” “Withdrawing missiles from Turkey had nothing to do with the defense of Cuba,” he remembered thinking about the Soviet rationale for installing their missiles on the island. “Cuba was defended by saying: Please remove the naval base; please, stop the embargo and the pirate [exile] attacks.” He remembered asking Khrushchev to “read that part about the missiles in Turkey” again. “He laughed that mischievous laugh of his. He laughed, and that was it. I was sure they were not going to repeat it again, because it was like that old phrase about bringing up the issue of the noose in the home of a man who was hung.”

Document 5

National Security Archive Cuba Collections

Some two weeks after the missile crisis abated, the Pentagon’s Office of International Security Affairs (ISA) produced a lengthy report on the lessons to be learned from the nuclear standoff. Unaware of the secret missile exchange and the series of mistakes, misjudgments, miscommunications and near-confrontations between U.S. and Soviet forces, the analysis casts the crisis as “a controlled conflict” and draws a number of inaccurate lessons from the episode. The ISA study judges that the Soviets installed the missiles as a deliberate test of U.S. resolve—“to display to the world, and especially to our allies, that the U.S. is too indecisive or too terrified of war to respond effectively to major Soviet provocation.” The crucial lesson, therefore, is that U.S. decisiveness to respond with “serious military action”—to ready an attack on the missile bases and a massive invasion of Cuba—was responsible for the successful outcome of the crisis. “The Soviets saw they were going to face conflict in Cuba and lose,” the study concludes, and therefore they withdrew the missiles.