Washington, D.C., February 5, 2020 – In the eyes of U.S. intelligence and the military services, the greatest threat to American national security during the early Cold War was the emerging Soviet missile program with its ability to deliver nuclear weapons to targets across the United States. Before the era of satellite surveillance, the U.S. scrambled to develop ever more effective intelligence-gathering methods, notably the U-2 spy plane, spurred on by having missed practically every important Soviet breakthrough of the time – including the first intercontinental ballistic missile tests and the world-changing Sputnik launches.

Early U.S. monitoring of Soviet missile activities is an important part of the history of nuclear weapons and even has parallels to the challenges faced today in tracking the programs of adversary states such as North Korea and Iran. Unfortunately, most of the record, even six or seven decades later, remains highly classified.

However, working with declassified materials from CIA and other sources, James E. David, curator of national security space programs at the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum, has pieced together a fascinating part of the story of the U.S. missile-tracking effort up to 1957. David’s last E-Book for the Archive described American spying on Communist military parades during the Cold War.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Starting to Crack a Hard Target

By James E. David

Intelligence on Soviet weapons systems during the Cold War was critical to U.S. civilian and military policymakers to assess the nature and scope of the threats they posed and to determine the size, composition, and weapons of U.S. forces. Soviet nuclear weapons were the top priority because of their unprecedented destructive power.

The USSR initially had only bombers with which to deliver these weapons. Just as the United States, however, it was developing surface-to-surface missiles to carry them and other missiles for such purposes as air defense. Missiles were the most threatening nuclear delivery system because they could hit targets very quickly and there were no defenses against them.

U.S. intelligence agencies faced enormous challenges in acquiring information on the Soviet missile program, and early assessments reflected the uncertainty resulting from the lack of timely and accurate data. Foreign missile programs are, of course, still a top priority intelligence target today. Although the collection and analytical resources are much more numerous and capable today, there are many more programs (e.g., Iran and North Korea) that require coverage. Additionally, in contrast to the Soviets in the early years of their missile program, apparently most nations encrypt their telemetry today.

Most U.S. government records on the early intelligence efforts against the USSR’s missile program remain classified today. The Central Intelligence Agency’s Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room has many more relevant declassified records than any other repository. It includes finished intelligence reports such as National Intelligence Estimates and related materials. However, except for overhead photography from the U-2 there has been very little released on the other vital technical intelligence efforts (particularly radar intelligence and signals intelligence). Similarly, there is virtually no available information on cooperation with the British in this field.

The National Security Agency, Joint Chiefs of Staff, Office of the Secretary of Defense, and the intelligence organizations of the three armed services certainly have large numbers of relevant records from the period in question. Except for a few heavily redacted National Security Agency histories, however, they are still classified.

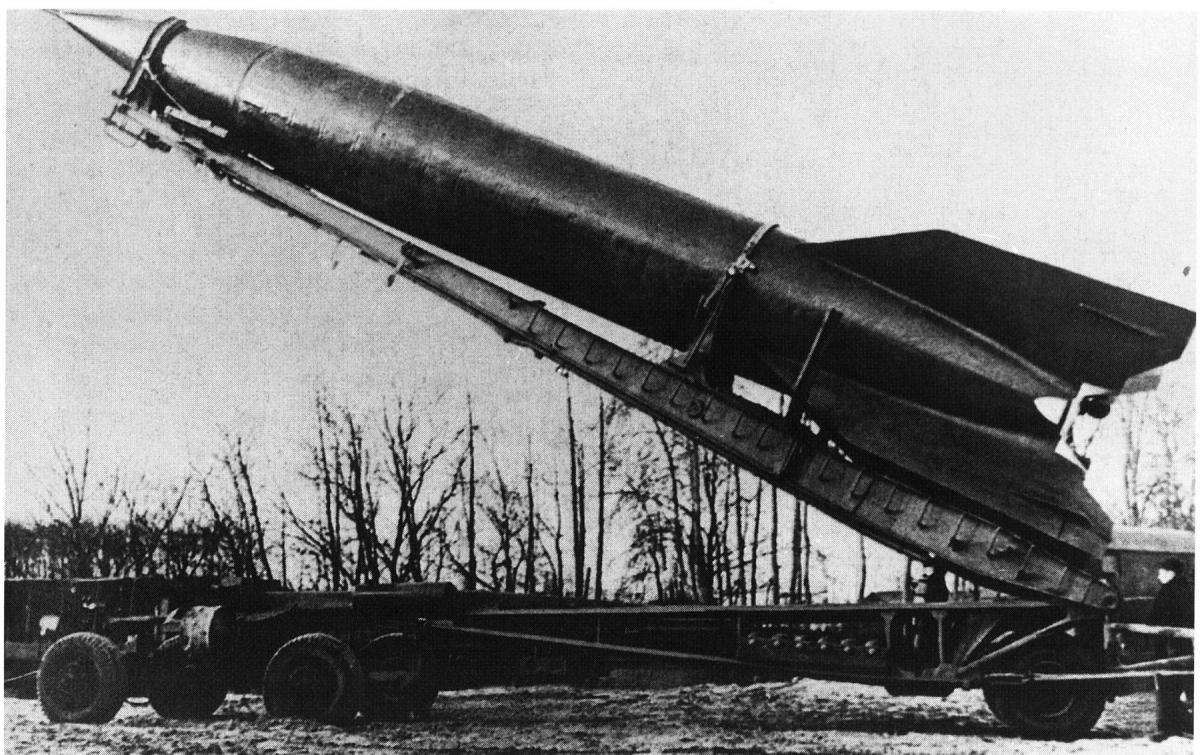

The Germans had the most advanced missile program of any nation during World War II. They had built the world’s first cruise missile (V-1) and ballistic missile (V-2) and launched many at targets in Belgium, France, and Great Britain. The Germans had also developed the first air-to-surface missiles and used them against allied ships in the Mediterranean and had built but not employed the first surface-to-air missiles.[1]

Just as the United States did after the war, the USSR exploited technical specialists and equipment from the German missile program to bolster their own efforts. The Soviets initially utilized German facilities and personnel in eastern Germany and moved their own scientists there to gain knowledge and experience. They then moved complete missiles, missile parts, technical records, manufacturing and testing equipment, and German personnel to several sites in the USSR beginning in 1947. In contrast to the United States, however, the Soviets sent almost all the scientists back to East Germany by 1953 and the few remaining ones by 1955.[2]

Human sources that had fled to West Germany were the only intelligence source on the Soviet missile program until the early 1950s. At the end of the war, the British established Project DRAGON to interrogate German scientists from various weapons programs. It is unknown how long this effort continued, but they undoubtedly shared some or all the intelligence with the United States. The U.S. Air Force set up Project WRINGER in Germany in 1948 to acquire all types of intelligence from defectors and refugees. Three years later, it became part of the combined armed forces/Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Defector Reception Center. These agencies created a separate organization, the Returnee Exploitation Group, in Frankfurt later in 1951 specifically to interrogate German scientists.[3]

This human intelligence (HUMINT) revealed that the USSR had an extensive missile program. It identified many of the Soviet scientists involved in the program and the locations and purposes of several installations. Germans were at the Kapustin Yar test range southwest of Stalingrad in 1947 for the testing of V-2s captured intact or assembled from parts. They participated in the development of improved V-2s (designated R-10 through R-14) and V-1 (designated R-15) starting the following year. Several missiles that had longer ranges and payload capacities than the V-2 had reached their final design stage by the time direct German involvement in these projects ended in 1951. Development of surface-to-air and air-to-surface missiles also began shortly after the war, but direct German participation in these projects ended in the early 1950s. However, no missile of any type they had worked on ever became operational. The Soviets had a separate missile development program to which the Germans had no access.[4]

The interrogations provided important intelligence but there were still huge gaps. For example, there was no information on the types, numbers, and performance characteristics of any missiles the Germans had not worked on; the types, numbers, locations, and performance characteristics of any deployed missiles; or the locations, features, and purposes of many missile program installations.

The early intelligence reports based on HUMNT acknowledged its limitations and over time proved wrong in many regards. U.S. intelligence agencies needed to employ various technical intelligence systems to obtain timely and accurate information. However, building and deploying these assets would take many years.

Although almost all the details remain classified, communications intelligence (COMINT) began furnishing data on the Soviet missile program in the early 1950s. Under the direction of the National Security Agency (NSA), Air Force Security Service, Army Security Agency, and Naval Security Group ground stations around the world were the most important platforms intercepting Soviet radio traffic at the time. In 1953, each began building large, permanent sites in Turkey that were critical in collecting traffic on the missile program from the western USSR. Their installations in Alaska and Japan undoubtedly intercepted most of the communications in the Soviet Far East. While processing of some intercepts took place in the theaters, the NSA conducted the majority in the United States.[5]

COMINT provided information on flight tests of several different short- and medium-range missiles at the Kapustin Yar range beginning in October 1953. From that date through May 1958, intercepts disclosed a total of 70 successful tests, 24 cancellations, 1 failure, and 23 with unknown results. In 1955, COMINT revealed the start of construction by the Ministry of Defense of possible missile program installations at a site in the Kazakh SSR (eventually designated Tyuratam) and at Klyuchi on the Kamchatka Peninsula. It monitored the building through the end of major construction in 1956. COMINT disclosed that the Soviets used massive amounts of concrete at Tyuratam for launch pads and blockhouses and were installing railroads, electronic facilities, and power and water systems. The intercepts evidently identified some of the scientists whose names had first appeared in interrogation reports as being involved in the Tyuratam project.[6] As shown in the excerpts from the Current Intelligence Bulletin from the fall of 1957 set forth below, COMINT revealed signs of possible upcoming launches at Tyuratam by monitoring transport flights to and from the facility, practice countdowns, communications between Tyuratam and Klyuchi, and communications on Klyuchi’s internal network.

Telemetry was another valuable source of intelligence on Soviet missile activity. Telemetry is the measurement of variables such as temperatures, acceleration, vibrations, propellant levels, and thrust chamber pressures during a rocket or missile’s flight. After conversion into electrical signals, the vehicle radios the signals to ground stations so controllers can assess the performance of the vehicle’s components. Derived from the interception and analysis of these signals, telemetry intelligence (TELINT) provided considerable information on the design and performance characteristics of rockets and missiles.[7] However, the available evidence indicates that the first TELINT collected was in 1958.

The Air Force Security Service built a specialized radar at Diyarbakir, Turkey, in 1955 to collect radar intelligence (RADINT) on missiles launched from Kapustin Yar. It detected them at or shortly after launch and tracked them during flight. Reduction of the recorded data at the Air Force’s Foreign Technology Division at Wright-Patterson AFB in Ohio determined the trajectory and thus the range. The radar detected and tracked over 500 missile launches from June 1955 to March 1964. A second radar installed in 1964 started collecting information on the size and configuration of vehicles launched from Kapustin Yar.[8] It is unknown when comparable radars began coverage of Tyuratam.

Imagery intelligence (IMINT) provided the locations and details of missile testing and deployment complexes, downrange instrumentation sites, impact areas, engine test facilities, and manufacturing plants. In contrast to HUMINT, COMINT, and RADINT, there is a considerable amount of declassified IMINT on the Soviet missile program through 1957.

Air Force and Navy overflights of the USSR began in 1947, but almost all photographed airfields, radars, and other targets near the borders. From 1952-1956, the Air Force conducted many overflights under the SENSINT program. There were few deep-penetration missions, however, and none photographed any missile program installations. The Royal Air Force did conduct several deep-penetration flights over the western portions of the USSR from 1952-1955, but they did not photograph any either.[9]

In 1954, President Dwight Eisenhower approved building the U-2 to perform overflights of the Soviet Union to locate and image bomber bases, nuclear facilities, naval bases, missile facilities, and other important military installations. It would fly higher than any existing reconnaissance aircraft and officials believed Soviet air defenses could neither detect nor successfully attack one for several years. Eisenhower tightly controlled the flights because of their extremely provocative nature and frequently rejected proposed missions or changed a proposed flight path. Following three missions over Eastern Europe, the first four overflights of the USSR were flown from 4 July to 10 July 1956 and covered parts of the western portion of the country. Eisenhower turned down additional missions targeting the USSR and Eastern Europe until November of that year. From that point to late April 1957, U-2s conducted three missions over Eastern Europe, one peripheral reconnaissance flight in the Black Sea and Caspian Sea regions (carrying an electronic intelligence sensor only), and one overflight mission.[10]

On 6 May 1957, Eisenhower approved a limited number of overflights of known and suspected guided missile and nuclear program targets. An 8 June mission targeted but did not successfully photograph Klyuchi on the Kamchatka Peninsula, the site COMINT indicated probably had some connection to Tyuratam. Another flight 12 days later acquired some useful imagery of it. This was the first Soviet missile program installation imaged by aerial reconnaissance. A 5 August mission targeted Tyuratam, but since mission planners did not know its exact location it only acquired oblique photography that confirmed its location but provided few details. Another flight later that month flew directly over the installation and collected excellent imagery. U-2s acquired excellent photography of Kapustin Yar on 10 September and Klyuchi six days later. They did not image either Tyuratam or Kapustin Yar again until 1959 and never photographed Klyuchi again.[11] Systematic coverage of these and other missile program installations did not begin until the advent of IMINT satellites in 1960.

As the intelligence reports set forth below illustrate, once these technical intelligence systems began operations in the mid-1950s they provided increasing amounts of critical data. However, at the end of 1957 there were still major gaps that were not filled for many years.

The documents

Document 01

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

An interrogation of an individual whose identity is still classified disclosed that neither of the Fahrbare Meteorological Station trains (built by the Germans to carry and launch V-2 ballistic missiles) had arrived in Moscow yet. Additionally, a German mathematician involved in guided missile research had been sent to the USSR the previous year.

Document 02

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

Interrogations of returned German POWs whose identities are still classified revealed that the Soviets established a guided missile factory in Kaliningrad near Moscow in 1947 to produce missiles based on German V-weapons. About 50 German and up to 70 Soviet engineers worked at the installation. Up to early 1948, it assembled complete V-2 missiles from parts made there and seized in Germany.

Document 03

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

A joint U.S.-British team evidently prepared this report that covered the next five years. It estimated that by 1952 an improved V-2 might be ready for initial production and that by the end of that year series production of about 700 per month might be established. The report also estimated that by 1951 an improved V-1 might be ready for production.

Document 04

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

Based on fragmentary evidence, this heavily redacted article concluded that the USSR probably had started a production program of improved versions of the V-1 and V-2.

Document 05

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

Based on interrogations of a German scientist whose identity is still classified, this report set forth a brief history of the Soviet guided missile program, the contributions of Nazi scientists, and some of the problems the program encountered.

Document 06

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

National and Special National Intelligence Estimates were among the highest-level intelligence reports. The CIA prepared them with input from all the intelligence agencies and then submitted them to the interagency Intelligence Advisory Committee (IAC) for approval. This one addressed the capabilities of the Soviets to attack the continental United States with nuclear and other weapons and concluded that aircraft would be the delivery system. In the brief section on guided missiles, it concluded that there was an extensive R&D program into improving V-1s and V-2s but ‘no positive information” that any missiles were in series production.

Document 07

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

Director of Central Intelligence Dulles undoubtedly sent this memo to President Dwight Eisenhower. As a follow-on to the British Canberra, it set forth the need for a new high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft to acquire critical photographic and electronic intelligence during overflights of the USSR and its allies. In a meeting with Dulles and other high-level advisers on the same date, President Eisenhower approved the project but directed that he would review the plans for any overflights. The aircraft was soon designated the U-2.

Document 08

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

The Current Intelligence Bulletin replaced the Daily Summary in February 1951 as the daily intelligence digest for the president. This entry describes the construction of launch complexes in the Moscow area that analysts assessed as probable sites for surface-to-air missiles. Visual observation by U.S. or allied military attachés or other diplomatic personnel undoubtedly provided the information for this entry. The actual deployment of missiles at some of the sites was initially seen in 1955, the first known operational missiles of any type that had been observed by U.S. or allied officials.

Document 09

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

In July 1955, the IAC created the interagency Ad Hoc Guided Missile Intelligence Survey Committee to evaluate the intelligence effort against the Soviet missile program. The committee unanimously agreed in its report that the collection efforts against the program were inadequate and exploitation of new technical intelligence collection systems was required. However, the Department of Defense (DoD) members (Army, Air Force, Navy, Joint Staff, and NSA) disagreed with the civilian members (Atomic Energy Commission, CIA, and Department of State) on how to organize and conduct the collection effort.

Document 10

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

This estimate updated National Intelligence Estimate 11-6-54, “Soviet Capabilities and Probable Programs in the Guided Missile Field,” from October 1954, the first on the Soviet missile program. NIE 11-12-55 concluded that the USSR had an extensive program developing all types of missiles. Based on new but still fragmentary intelligence, it provided more details on the surface-to-air missiles that probably were being deployed around Moscow and surface-to-surface missiles. With respect to intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), the estimate concluded that the USSR had the capability to develop them with a range of 5,500 miles and a large-yield nuclear warhead and such a project “is probably being undertaken on a very high priority.” It assessed that “the first operational model could be ready for series production by 1960-1961.”

Document 11

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

The DoD members of the IAC finally agreed to establish a new Guided Missile Intelligence Committee (GMIC) in January 1956. With members from all the IAC agencies, it had several responsibilities, including reporting on foreign guided missile developments, establishing objectives for guided missile intelligence, and reviewing the collection efforts to satisfy them.

Document 12

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

One possible new intelligence collection system was acoustic sensors, which were being tested at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico.

Document 13

Record Group 340, Entry A-1 1-E, Box #1, National Archives, College Park Maryland

The Air Force Security Service radar at Diyarbakir, Turkey, detected and tracked at least 22 missiles tested at Kapustin Yar in 1956. One was a short-range missile and the remainder flew to distances between 480 and 740 nautical miles.

Document 14

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

Covering all types of missiles and based in part on new but still incomplete intelligence acquired since NIE 11-12-55, this estimate provided more details on the surface-to-air missiles deployed around Moscow and several others. With respect to ICBMs, it concluded that although there was still no direct evidence of their development the Soviets very likely had a high-priority program and it was “probable that the USSR could have ready for operational use in 1960-61 a prototype ICBM capable of carrying a 1,500 pound payload to a maximum range of 5,500 n.m.”

Document 15

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

Published shortly after NIE 11-5-57, this document set forth the major gaps in scientific and technical intelligence, economic intelligence, and the operational status and deployment of missiles that were evident in its preparation; it further directed the intelligence agencies to take several steps to address them.

Document 16

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

Still-classified COMINT disclosed that construction on two new guided missile facilities had started in 1955 and was still ongoing. One was a probable launch complex near Tyuratam in the Kazakh SSR. The other was a probable terminus facility at Klyuchi on the Kamchatka Peninsula that could monitor the terminal phase of an ICBM test flight or a satellite placed in orbit. The authors believed the USSR might be preparing to test an ICBM or orbit a satellite within a year utilizing these facilities.

Document 17

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

The Diyarbakir radar detected and tracked two two-stage vehicles launched from Kapustin Yar in May. The first stage fell to Earth about 50 nautical miles downrange while Soviet radars at the mid- and far-range stations were continuing to observe another object. These were the first two-stage vehicles known to have been launched and were probably testing components for either an ICBM or a rocket for orbiting a satellite.

Document 18

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

RADINT from the Diyarbakir facility revealed that the Soviets had recently launched a new missile from Kapustin Yar that flew 950 nautical miles downrange. All known missiles tested prior to this had not flown over 650 nautical miles.

Document 19

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

The Soviets tested the third 950-nautical-mile ballistic missile from Kapustin Yar on 13 July, which the Diyarbakir radar detected and tracked.

Document 20

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

This GMIC memo set forth its contribution to the IAC’s annual report to the NSC on the status of the foreign intelligence program. Despite improved intelligence during FY 1957, there was still little technical information on the missiles currently deployed and under development, almost no data on missile production facilities and their capabilities, and only fragmentary evidence on the military doctrine for employment of missiles.

Document 21

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

On 20 June 1957, Mission 6005 acquired the first U-2 photography of Klyuchi and other areas on the Kamchatka Peninsula. This report was based in part on the imagery and COMINT that is redacted (EIDER, one of the classification markings, was a COMINT compartment). The flight did not detect any evidence of a launch complex. Although the areas most likely to contain instruments used at a test range terminus were cloud-covered and the camera’s resolution would not permit detection and identification of most such equipment, the report concluded that the area was probably a terminus.

Document 22

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

This memo, arguing for increased use of the U-2 for observing Soviet strategic capabilities, stated that good imagery of Soviet missiles and their launch complexes had not been obtained yet and was essential to determine the size, types, payload capacities, propulsion systems, and guidance systems of the missiles. U-2 Mission 4035 had acquired the first photography of the new Tyuratam launch complex on 5 August, but it was oblique and thus provided only limited information.

Document 23

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

U-2 Mission 4058 on 28 August acquired the first good photography of Tyuratam. Among other things, it disclosed one completed launch area, another probable one under construction, rail lines, and numerous other ground support facilities. The report concluded that “certain key support and operational facilities were either completed or in a stage of completion so advanced as to permit operational launchings from this installation as of late August 1957.”

Document 24

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

U.S. intelligence agencies had no collection systems to detect and track or collect telemetry from missiles launched from Tyuratam at the time. Knowledge of the first ICBM test flight came from a TASS announcement on 26 August and of the second test on 7 September from a remark made by Khrushchev to Edouard Daladier, a French politician. Based on the extensive flight testing at Kapustin Yar since 1953 and still-classified COMINT, it was assessed that “The USSR has probably flight-tested two intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) vehicles, the first on 21 August 1957 and the second on 7 September 1957.”

Document 25

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

Submitted pursuant to the direction of the IAC in its 21 March Post-Mortem on NIE 11-5-57, the Scientific Estimates Committee reported that it had made little progress in the last six months in improving intelligence collection on the Soviet missile program. Acoustic and infrared systems to improve detection of objects in space were under investigation but were not ready for deployment.

Document 26

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

U-2 Mission 6008 on 16 September again covered Klyuchi and other areas on the Kamchatka Peninsula. This preliminary report stated that the photography was excellent and there was no cloud cover. Among other things, it disclosed several possible electronic installations.

Document 27

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

Mission 4059 on 10 September 1957 acquired the first U-2 photography of Kapustin Yar. This excerpt from the Mission Coverage Summary briefly describes the different parts of the complex imaged. Among other things, there were several completed probable launch pads, several suspected launch pads under construction, rail lines, and many confirmed or possible other ground support facilities.

Document 28

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

The Soviets had announced the previous day that they had successfully launched a satellite – later dubbed Sputnik – into orbit. Various civilian stations had already picked up its signals. U.S. officials learned of the first-ever launch, which effectively marked the start of the space race, through the announcement.

Document 29

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

The GMIC had recently created the Subcommittee for Guidance to Collectors to examine improving collection efforts. It addressed both peripheral and internal collection systems, but all the details are redacted; only the conclusions and recommendations have been released.

Document 30

This brief memo indicates that Deputy Director of the CIA Gen. Cabell had shown President Eisenhower U-2 imagery of several key targets, including Tyuratam, in late September.

Document 31

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

One week after Sputnik, still-classified COMINT evidently suggested that a launch of a second satellite was imminent or, less likely, another ICBM test flight.

Document 32

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

Still-classified COMINT indicated that beginning on 25 October the Tyuratam and Klyuchi complexes had resumed activities like those that preceded the first ICBM test flight on 21 August and the Sputnik 1 launch on 4 October. Analysts concluded that from the pattern monitored they were probably a practice for an upcoming ICBM test flight or satellite launch.

Document 33

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

Moscow Radio announced on 3 November the launch of a second satellite (Sputnik 2) carrying a live dog after it completed at least one orbit. The reported weight of satellite meant that the propulsion system in the rocket that launched it, if used in an ICBM, could deliver a 2,000 lb. warhead to 5,500 nautical miles. U.S. officials apparently learned of the launch from this announcement.

Document 34

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

Still-classified COMINT detected on 5 November that Tyuratam was engaging in activities that analysts assessed to be a practice rather than an actual launch attempt.

Document 35

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

Beginning on 13 November, still-classified SIGINT detected the Soviet KRUG high-frequency direction-finding network tracking balloons that evidently acquired upper atmosphere data. The KRUG network had tracked balloons a few hours prior to the launches of Sputniks 1 and 2. Starting on 5 November, still-classified COMINT had intercepted daily 4- and 5-hour practice countdowns at Tyuratam, communications between Tyuratam and Klyuchi, and communications on the Klyuchi facility network. These were the most extensive practice operations monitored to date, and analysts assessed them to be for a satellite launch or ICBM test.

Document 36

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

The practice tracking of balloons by the KRUG network ended on 15 November, and still-classified COMINT detected the resumption of practice activities at Tyuratam and Klyuchi on 23 and 24 November. Based on Soviet statements that it would launch 12-14 satellites during the International Geophysical Year, analysts believed that these were more likely preparations for a satellite launch than an ICBM test.

Document 37

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

This is the introductory section of the Special Engineering Analysis Group’s lengthy report. Established by the IAC, its mandate was to analyze U-2 photography of Kapustin Yar, Tyuratam, and Klyuchi; COMINT; ELINT; RADINT; and other intelligence to determine the features of these three facilities and the types, sizes, performance, and development status of Soviet missiles and rockets.

Document 38

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

Still-classified COMINT monitored transport aircraft flights that had preceded previous launches at Tyuratam and indicated a possible satellite launch or ICBM test in early December.

Document 39

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

This list briefly describes the several types of Air Force collection directives, guidance letters, and guidance manuals from the mid-1950s that were used to direct and assist units in acquiring intelligence on the Soviet missile program. The actual documents themselves remain classified.

Document 40

CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

Except for sightings of the SA-1 surface-to-air missile that had been deployed at sites around Moscow beginning in 1955, this parade was the first time U.S. and allied officials were able to observe and photograph several short- and medium-range surface-to-surface missiles. Significantly, the Soviets did not display either their first-generation ICBM or the launch vehicle derived from it.

Notes

[1] [redacted], The Soviet Land-Based Ballistic Missile Program, 1945-1972 (National Security Agency, 1975), Section I, pp. 1-7 (accessed 12 January 2020 at https://www.theblackvault.com/)

[2] Ibid.

[3] Gregory W. Pedlow and Donald E. Welzenbach, The Central Intelligence Agency and Overhead Reconnaissance, The U-2 and OXCART Programs, 1954-1974 (Washington D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency, 1992), p. 2 (accessed 14 January 2020 at https://www.governmentattic.org/22docs/CIAoverheadRecon_1992updt.pdf)

[4]The Soviet Land-Based Ballistic Missile Program, 1945-1972, Section I, pp. 8-25.

[5] Ibid, Section IV, pp. 1-2. Thomas R. Johnson, American Cryptology during the Cold War, 1945-1989, Book I: The Struggle for Centralization 1945-1960 (Center for Cryptologic History, National Security Agency, 1995), pp. 122-125 (accessed 14 January 2020 at https://www.nsa.gov/Portals/70/documents/news-features/declassified-documents/cryptologic-histories/cold_war_i.pdf)

[6]The Soviet Land-Based Ballistic Missile Program, 1945-1972, Section I, pp. 1-7 and Section IV, pp. 1-14.

[7] David S. Brandwein, “Telemetry Analysis”, Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 8, No. 4 (Fall 1964) (accessed 15 January 2020 at https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/1964-09-01b-A.pdf). Dino A. Brugioni, Eyes in the sky, Eisenhower, the CIA, and Cold War Aerial Espionage (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2010), pp. 204-206.

[8] Stanley G. Zabetakis and John F. Peterson, “The Diyarbakir Radar”, Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 8, No. 4 (Fall 1964) (accessed 15 January 2020 at https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/1964-09-01b-A.pdf)

[9] Robert S. Hopkins III, Spyflights and Overflights, U.S. Strategic Aerial Reconnaissance, Volume 1, 1945-1960 (Manchester: Hikoki Publications, 2016), pp. 47-56.

[10]The Central Intelligence Agency and Overhead Reconnaissance, The U-2 and OXCART Programs, 1954-1974, p. 122-128, 134.

[11] Ibid, pp. 127-128, 133-139, 163-170.

Use the online HTML, CSS, JavaScript tool collection to make websites easily.