Washington, D.C., April 12, 2021 – Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin’s historic spaceflight 60 years ago, which made him the first human in space, prompted President John F. Kennedy to advance an unusual proposal – that the two superpowers combine forces to cooperate in space. In a congratulatory letter to Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, posted today by the nongovernmental National Security Archive, Kennedy expressed the hope that “our nations [can] work together” in the “continuing quest for knowledge of outer space.”

Kennedy’s letter is one of many records in the American and Russian archives that show that the two ideological rivals have not only engaged in a space race but have also cooperated for decades. In fact, as the ongoing joint activities involving the International Space Station demonstrate, space has been one of the few spheres of collaboration that have survived the trials and tensions of the Cold War, keeping both countries engaged in constructive competition as well as in joint efforts to expand human frontiers.

Today’s posting begins a two-part series exploring this often-overlooked chapter in the relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union, and later Russia. The materials in the first tranche cover events from Gagarin’s flight to the celebrated Apollo-Soyuz mission. The second posting in early May will deal with the post-Cold War period.

* * * * *

On April 12, 1961, the Vostok 1 rocket lifted off from Baikonur Cosmodrome, carrying Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin into history as the first human to reach outer space. The launch of the first satellite, Sputnik, in 1957, and the success of Gagarin’s flight, showed the Soviet Union in the lead in the U.S.-Soviet Space Race. Historical memory in the United States and the Soviet Union in relation to space tends to focus on this competition between the two nations, with the events leading to the successes of Yuri Gagarin, Alan Shepard, Valentina Tereshkova, and Neil Armstrong among the best known results. Less discussed are the long years of cooperative efforts between the American and Soviet space programs, and then the American and Russian space programs that represented diplomatic and scientific successes in times of significant mutual distrust and tension.

Early efforts for space cooperation, and the continuation of cooperative programs, show the importance of scientific work as an avenue for constructive dialogue between adversarial states. Space cooperation provides nations that are unable for political reasons to work together on other issues the opportunity to pool resources and establish links between scientific communities that benefit scientific capabilities and human knowledge, as well as promote general relations between rivals. Today, as cooperative space efforts are faltering under once again worsening relations, it is instructive to return to these early efforts to remember that cooperation is not only possible, but mutually advantageous.

This post features documents sourced from presidential libraries, the online archives of the Central Intelligence Agency and the Department of State, and two translated documents from Russian archives. The documents in this post show the efforts that both sides put into working together, despite the tumultuous nature of U.S.-Soviet relations that had built up over the course of a lengthy ideological power struggle. In 1961, on the eve of Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin’s launch, Soviet Chairman of the Council of Ministers Nikita Khrushchev dictated a series of proposals for celebrations after the flight, and a message to be sent out around the world commemorating the achievement as both proof of the power of Marxist-Leninist teachings and an achievement for all of humanity (Document 1). Following Gagarin’s flight, U.S. President John F. Kennedy sent a telegram to Khrushchev congratulating him on the program (Document 2). In the telegram, Kennedy also stated that it was his “sincere desire that in the continuing quest for knowledge of outer space our nations can work together to obtain the greatest benefit to mankind.” President Kennedy continued to pursue space cooperation with the Soviets in 1962 and 1963, as can be seen in a 1962 letter from President Kennedy to Chairman Khrushchev containing possibilities for cooperation (Document 3). Following the destabilizing events of the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, attempts to cooperate continued. A November 1962 telegram from Special Envoy Georgy K. Zhukov following his conversation with Presidential Advisor John J. McCloy shows the Kennedy administration’s attempts to mend the relationship, with space being mentioned as a possible area for cooperation (Document 4). In 1963, President Kennedy gave a speech before the General Assembly of the United Nations suggesting a joint U.S.-Soviet lunar expedition (Document 5).

Cooperative efforts continued following Kennedy’s assassination in 1963. Progress in that area as well as “Soviet performance and attitudes thus far,” including in regard to a possible crewed lunar landing, are discussed in a series of letters between the Johnson White House and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) head James Webb (Document 6). The Johnson administration’s National Security Action Memorandum No. 285 on cooperation with the USSR on outer space matters and the Nixon administration’s National Security Decision Memorandum 70 on international space cooperation show the continuing high-level interest in cooperative efforts with the Soviet space program, both leading up to the moon landing and following it (Document 8 and 10).

Progress also continued on a more technical basis. Talks on data-sharing held by Hugh Dryden of NASA and Anatoly Blagonravov of the Soviet Academy of Sciences had led to an agreement in 1962 and open communication in the areas of space medicine and satellite meteorological data. Talks continued between the two scientists in 1964, resulting in a second Memorandum of Understanding and the continuation of the so-called Dryden-Blagonravov Agreement (Document 9).

In October 1971, the first meeting of the Joint US/ USSR Working Group on Space Biology and Medicine was held in Moscow, followed by another gathering the next year, which prompted a report in the Central Intelligence Agency’s Central Intelligence Bulletin on Soviet interest in NASA’s space suit technology (Document 11 and 12). President Richard Nixon, speaking to Soviet Academician Vadim Trapeznikov and Soviet Ambassador Anatoli Dobrynin, reaffirmed U.S. interest in cooperation, stating that “while science is not as spectacular as SALT [the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks], both are important and greatly affect what we can do in the future.” (Document 13)

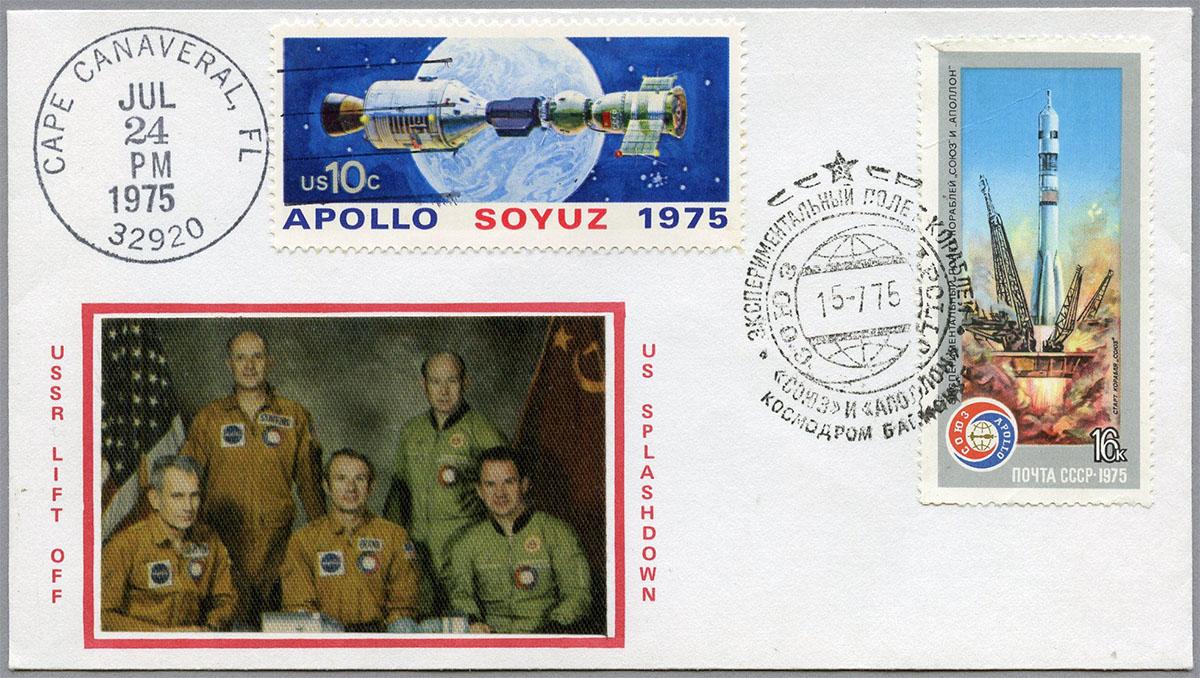

The crowning achievement in space cooperation in the 1970s was the 1975 Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP), which involved the docking of the Soviet Soyuz capsule with the U.S. Apollo module. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, in preparation for a 1974 meeting with Soviet Foreign Minister Gromyko, noted the need to discuss further cooperative efforts after the completion of the ASTP (Document 14). President Gerald Ford met with the Soviet cosmonauts participating in ASTP in September 1974, describing the project as “an important step forward in U.S.-Soviet relations.” (Document 15) The astronauts and cosmonauts launched for the ASTP mission on July 15th, 1975, with President Ford wishing the participants luck in “opening a new era in the exploration of space.” (Document 16) Following the successful completion of ASTP, the astronauts and cosmonauts participated in joint tours of the U.S. and the Soviet Union, with General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev describing the participants as “messengers of good will representing the aspiration of the people of the two countries toward peaceful cooperation.” (Document 17)

Space cooperation remained seemingly untouched by the deteriorating relations between the United States and the Soviet Union in the late 1970s and 1980s; it continued even after the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1979 and walked out of all arms control negotiations in response to the first deployments of Pershing missiles in Europe.

The International Space Station of today is the result of these collaborative efforts that have their roots in the 1960s, were tested in the 1970s, and continued throughout the 1980s and 1990s, even during and after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Part II of this posting will focus on the period after the end of the Cold War and the challenges it faces today

Read the documents

Document 1

Russian State Archive of Contemporary History

This translated document contains proposals from Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in connection with the launch of the Vostok spacecraft, which would make Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin the first human in space. Khrushchev discusses the need for a parade in Red Square and a reception in the Kremlin for Gagarin following his return. He also provides material for a statement to be released regarding the flight. The message speaks of the event as being an accomplishment of the Soviet Union and a “demonstration of Marxist-Leninist teachings,” but also as an accomplishment of all of humanity, “when the development of science has allowed a person to penetrate into space and return.”

Document 2

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library

This document is the press release of a telegram sent by President John F. Kennedy on April 12, 1961, to Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev following the successful flight of Yuri Gagarin, the cosmonaut who had just become the first human in space. President Kennedy congratulates Khrushchev and the Soviet space program for this achievement. Kennedy also mentions his “sincere desire that in the continuing quest for knowledge of outer space our nations can work together to obtain the greatest benefit to mankind.”

Document 3

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library

This letter, sent by President John Kennedy to Soviet General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev, discusses the possibilities for U.S.-Soviet cooperation in outer space. President Kennedy suggests “desirable cooperative activities” such as “the joint establishment of an early operational weather satellite system,” sharing operational tracking services, pooling data on space medicine, and work “in the field of experimental communications by satellite.” Kennedy states that “the tasks are so challenging, the costs so great, and the risks to the brave men who engage in space exploration so grave, that we must in all good conscience try every possibility of sharing these tasks and costs and of minimizing these risks.” Kennedy also brings up the idea of cooperating in “unmanned exploration of the lunar surface.”

Document 4

Archive of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation

This excerpt from a telegram from Soviet Envoy Zhukov to the Central Committee on his conversation with Presidential Advisor McCloy discusses “further prospects for American-Soviet cooperation that will open as a result of the settlement of the Cuban crisis.” McCloy suggests an agreement on the cessation of nuclear weapons testing, as well as an agreement banning the military use of space and a possible joint U.S.-Soviet space mission. A Soviet-American mission to Venus is specifically mentioned in the telegram.

Document 5

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library

In President Kennedy’s address to the 18th General Assembly of the United Nations, he addresses the threats to peace of the past twenty-four months, as well as recent successes in political cooperation, stating “the long shadows of conflict and crisis envelop us still. But we meet today in an atmosphere of rising hope, and at a moment of comparative calm.” The President adds “we may have reached a pause in the cold war- but that is not a lasting peace.” Kennedy notes key differences between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, but also his hopes for agreements between the two countries. He mentions his desire for U.S.-Soviet cooperation in space, in particular referencing the possibility of a “joint expedition to the moon.” He adds, “why…should man’s first flight to the moon be a matter of national competition?...Surely we should explore whether the scientists and astronauts of our two countries – indeed of all the world- cannot work together in the conquest of space, sending some day in this decade to the moon not the representatives of a single nation, but the representatives of all of our countries.” President Kennedy acknowledges the difficulty of such cooperation, as it will require “a new approach to the cold war” and “long and careful negotiation.” The President ends with the lines, “my fellow inhabitants of this planet: Let us take our stand here in this Assembly of nations. And let us see if we, in our own time, can move the world to a just and lasting peace.”

Document 6

Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library

A letter and a cover memo from NASA administrator James Webb to President Lyndon B. Johnson covers “possible projects for substantive cooperation in the field of outer space.” Webb mentions that the report “focuses upon possible cooperation in manned and related unmanned lunar programs,” and later remarks “personal initiative by you would still be required to extend this success to cooperation in maned lunar programs.” Webb also describes the recommended guidelines for negotiations with the USSR on space cooperation: “substantive rather than propaganda objectives alone; well-defined and comparable obligations for both sides; freedom to take independent action; protection of national and military security interests; opportunity for participation by friendly nations; and open dissemination of scientific results.” The report discusses possibilities for cooperation on a lunar program, the approach to achieve such a collaborative program, and related topics such as data sharing and operational cooperation. Also included is a February 4 memorandum from a staff member to National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy on the letter and report, in which it discusses the President communicating secretly with “K” (Khrushchev) in an attempt to get him to “personally oversee and expedite the Soviet response to our offers of cooperation, realizing the great difficulty any Chief of State has in getting the bureaucracy moving with alacrity particularly when mistaken notions of military security may be impeding performance.”

Document 7

Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library

This memorandum from National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy to President Lyndon B. Johnson discusses NASA Administrator James Webb’s report on “possible projects for substantive cooperation with the Soviet Union on outer space.” Bundy summarizes the report as containing “guidelines to govern negotiations with the Soviet Union that have a reasonable chance at success, yet protect our national interests.” Bundy states that “no immediate public action is recommended because we are in need of Soviet performance on present agreements.”

Document 8

Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library

National Security Action Memorandum No. 285 concerning cooperation with the USSR on Outer Space Matters draws on the NASA report to the president from January 31, 1964 (Document 6). The NSAM gives NASA President Johnson’s “general endorsement” to proceed with a program of cooperation. The president states that “by the first of May, the Soviet Union should have had ample opportunity to make its intentions with respect to cooperation clear to us.” Johnson asks to be kept informed of “the progress being made with the Soviet Academy of Sciences under the current agreement, and also of any Soviet response to our initiatives at the United Nations on cooperation in outer space.”

Document 9

Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library

Cooperation progressed at lower-levels of government during this period, as data-sharing efforts between the scientific communities of the U.S. and the USSR were expanded. This memorandum from NASA Administrator James Webb to President Lyndon B. Johnson covers the bilateral discussions between NASA Deputy Director Dr. Hugh Dryden and his Soviet counterpart, Academician Anatoly Blagonravov, which resulted in a Second Memorandum of Understanding between the two governments and a “protocol” providing for “further implementation of the existing bilateral agreement” and “new cooperation” in the area of space biology and medicine. Also mentioned is Dryden discussing the possibility of joint manned flight programs with Blagonravov. Webb also summarizes “Soviet performance and attitudes thus far” in areas such as satellite communications, space biology and medicine, and meteorological satellite cooperation, and a full report from NASA on space cooperation. He adds that beyond current action plans, “any more far-reaching overtures by the United States at the present time would appear to go beyond the Soviet’s current state of readiness.”

Document 10

Richard Nixon Presidential Library

This National Security Council decision memorandum discusses international space cooperation between the U.S. and the USSR. In the memorandum, National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger states that President Richard Nixon has “decided that space cooperation with the Soviet Union should be pursued simultaneously through high-level diplomatic and technical agency channels.” The memorandum also notes that the president does not want to formally communicate this interest in “closer space cooperation” to Premier Kosygin at the current time, but will consider it when it seems that a “concrete program proposal will be favorably received by the Soviet Union.”

Document 11

Central Intelligence Agency Digital Archive

This memorandum to the Central Intelligence Agency’s Assistant Deputy Director for Science for Technology Dr. Donald Steininger from NASA Office of DOD and Interagency Affairs’ Technical Coordinator Myron Krueger includes a copy of the recommendations of the Joint US/USSR Working Group on Space Biology and Medicine, held in implementation of the NASA/Soviet Academy agreement of January 1971, following their first meeting in October 1971 in Moscow. The group “examined biomedical data and results of manned flight programs and exchanged oral and written reports on the Soyuz and Apollo programs.” The group “developed the following recommendations for expanded and more regular exchange of space biomedical data in order to make maximum contributions to the safety and efficiency of manned space flight and to general medical knowledge,” which included holding yearly meetings to exchange data on human space flights, working sessions on certain topics of particular interest to both sides, such as the response of the cardiovascular and central nervous systems to the space flight environment, and specialist exchanges.

Document 12

Central Intelligence Agency Digital Archive

This Central Intelligence Bulletin from the CIA’s Directorate of Intelligence discusses Soviet interest in U.S. space suit technology. The report describes that during a joint US-USSR working group in space biology and medicine the Soviet participants expressed “great interest” in the suits used during the Apollo lunar landings, and mentioned a pending request to NASA to “buy several space suits from the US manufacturer.” The document notes that the Soviets have not used pressurized space suits on missions since 1969, and how the use of pressurized suits could have potentially saved the lives of the Soyuz 11 cosmonauts who died during re-entry in 1971. Also mentioned is the slower Soviet development of space suits in comparison to the United States, and how a “US-type suit also would be essential for a Soviet lunar landing.” The report adds that there “are indications that the Soviets are planning a manned space flight within the next few weeks.”

Document 13

Richard Nixon Presidential Library

This memorandum records a conversation between President Richard Nixon and Soviet Academician Vadim Trapeznikov, as well as Science Adviser Dr. Guyford Stever, Major General Brent Scowcroft, and Ambassador Anatoli Dobrynin. In this short meeting the participants discuss the importance of science cooperation, with President Nixon noting that “while science is not as spectacular as SALT, both are important and greatly affect what we can do in the future.” Trapeznikov states that “much brain power is used for destruction. We must use our brains to bring better life for all people on earth.” Nixon mentions the progress in scientific cooperation, saying that “we have moved from symbolism to the hard substance. General-Secretary Brezhnev and I share the same feeling. We want results….It doesn’t matter who is first because we will share the results.”

Document 14

Department of State FOIA Reading Room

This memo from Deputy National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger provides a status report on US-USSR bilateral proposals for Secretary Kissinger’s use during his May 7 meeting with Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko. Scowcroft discusses a second U.S.-Soviet space mission after the completion of the scheduled Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, saying that the Soviets are moving very slowly on it, possibly due to Soviet Academy of the Sciences President Keldysh’s “serious illness.” He adds that NASA has proposed a mission involving the USSR Space Station Salyut but the Soviet side has indicated that that would not be possible, and that “NASA has its doubts about the value of a second mission limited to Apollo and Soyuz spacecraft only.” Scowcroft suggests that Kissinger ask Gromyko “to shed light on the slow pace at which the USSR is moving.”

Document 15

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library

This briefing memo from Secretary Henry Kissinger to President Gerald Ford provides information for the president’s meeting with the three Soviet cosmonauts who are participating in the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. The memo covers the purpose of the visit, which is “to call attention to the importance you attach to the 1975 joint manned space mission for the contributions it is making to US-USSR space cooperation, the strengthening of US-USSR cooperation generally, and the effects of all countries working together on projects that broaden human knowledge.” Also included is background information on the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project and talking points for the meeting, such as “the flight has significance for all who believe that different countries can contribute to a better world by working together.”

Document 16

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library

This Department of State telegram contains President Ford’s pre-launch message to the U.S. astronauts and the Soviet cosmonauts participating in the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. In his message, President Ford says that together the astronauts and cosmonauts will be “blazing a new trail of international space cooperation,” and that their flight “has already demonstrated something else- that the United States and the Soviet Union can cooperate in such an important endeavor.” Ford speaks of the history of human spaceflight, saying “less than two decades ago Yuri Gagarin and then John Glenn orbited the earth, realizing the dreams of Tsiolkovsky, Goddard and others who believed firmly that man could fly in space.” The president adds that he is confident that the actions of the Apollo-Soyuz mission will “lead to further cooperation between our two countries.”

Document 17

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library

This letter from General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev to President Gerald Ford comes after astronauts Thomas Stafford, Vance Brand, and Donald Slayton’s visit to Moscow and cosmonauts Aleksey Leonov and Valeriy Kubasov’s visit to the U.S. following the successful completion of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. In the letter, Brezhnev describes the mission as “yet another confirmation of the fruitfulness of the course of the comprehensive improvement of Soviet-American relations we have jointly undertaken,” and remarks that he “willingly” shares Ford’s remarks “regarding the necessity of continuing this work.” Brezhnev describes the astronauts and cosmonauts as “messengers of good will representing the aspiration of the peoples of the two countries toward peaceful cooperation.”