Washington D.C., May 25, 2022 –The National Security Archive marks what would have been Anatoly Sergeyevich Chernyaev’s 101st birthday today with the publication for the first time in English of his Diary for 1982. At the time, Chernyaev was deputy director of the International Department of the Central Committee responsible for the International Communist Movement (ICM). Within a few years he became a close adviser to Mikhail Gorbachev and a leading theorist in the era of perestroika and glasnost.

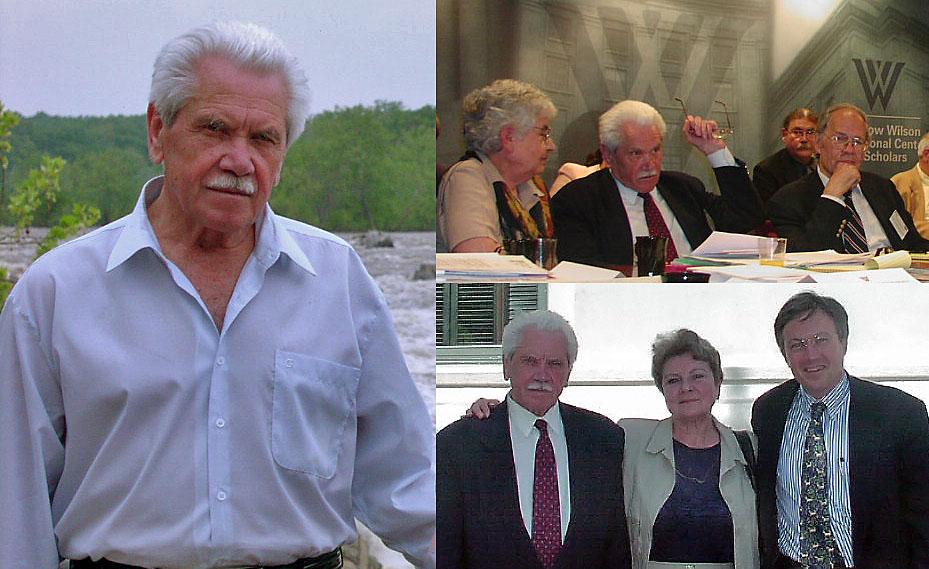

After the Soviet collapse, Chernyaev transformed into one of the most important and reliable sources of historical information for Western observers about the Soviet system and the Kremlin’s Cold War. An invaluable contributor to international scholarship, including conferences and research conducted by the National Security Archive, he ultimately donated his diary – which Pulitzer Prize-winning author David Hoffman called “irreplaceable” and “one of the great internal records of the Gorbachev years” – to the Archive. Every year, this organization translates and posts another installment of this extraordinary chronicle.

* * * *

Chernyaev’s diary for 1982 records many pivotal moments, notably the anticipation of Leonid Brezhnev’s death along with the gradual demise of the entire Soviet-led international communist movement and the rising hopes for reforms under the new leader. When Brezhnev actually dies in November, there comes a moment of suspense, but Chernyaev is relieved when Yury Andropov is selected as the new general secretary. Throughout the year, the author of the diary is actually hoping that the intelligent and energetic Andropov will pull the country out of its stupor. Despite Andropov's actions as head of the KGB, most reformers do not anticipate that the new leader's changes will include harsh disciplinary measures and suppression of all dissent – all of which is to come in 1983.

In 1982, Chernyaev’s duties are centered mostly on writing articles and speeches for powerful Central Committee International Department head Boris Ponomarev and meeting with leaders of foreign communist parties. A lot of these drafts are rebuttals to various communist leaders’ criticisms of the Soviet Union and the Soviet interpretation of Marxism. The year begins with the conflict with the Italian communists, who, in Chernyaev’s words, “expelled us from socialism” in reaction to martial law in Poland. Summarizing Italian party leader Enrico Berlinguer’s report, Chernyaev agrees that “the fate of the revolutionary process now depends on the ability of the Western European labor movement to overcome capitalism and create a socialist system that would integrate all the democratic achievements of European civilization,” which is quite stunning for a Soviet Central Committee official. At the same time, this entry shows Chernyaev’s forward thinking that he will eventually bring to Gorbachev.

Work for Ponomarev stopped being intellectually satisfying for the author of the diary, in a way becoming a burden that made him experience the everyday hypocrisy of the decaying system. As in previous years, Chernyaev devotes a lot of diary entries to the deteriorating situation in the economy and the absence of food and basic consumer goods in the stores. But even more so he chronicles the pervasive corruption in the upper echelons of power and in Brezhnev’s family. He describes Ponomarev’s deputy, Karen Brutents, coming back from Yemen and talking about shocking instances of corruption during visits of Brezhnev’s son-in-law, Dmitry Churbanov, to Third World countries.

1982 was a year of “significant” deaths. February saw the passing of the legendary Mikhail Suslov, the ideology secretary, and one of the most orthodox party figures. He worked with all Soviet leaders starting with Stalin and played the role of the “grey cardinal” in the rise of Nikita Khrushchev and Brezhnev. Chernyaev muses about Suslov’s legacy, noting his personal stoicism, moral authority among party members, and opposition to the personality cult. He notes also that Suslov never wanted to “become the ‘First,” but if he did, “he would have become one … in 1964.” In Chernyaev’s view, Ponomarev wanted to become Suslov’s successor, but was bitterly disappointed when Konstantin Chernenko took his place. In August, head of the influential Institute of World Economy and International Relations Nikolai Inozemtsev dies of a heart attack. And in November, the most anticipated death of 1982 takes the general secretary himself – Brezhnev.

Among other highlights of the year are the many important conversations between Chernyaev and other future “new thinkers,” like Georgy (Yury) Arbatov, Alexander Bovin, Brutents and Alexander Yakovlev, in which they share their assessment of the rotting political system and hopes for the future. Like Gorbachev in 1983, Chernyaev talks to Yakovlev during his visit to Canada in February 1982. He describes how Yakovlev “yearns for his homeland … rail[s] at the order of things, the bosses, the mess,” and asks the eternal questions of Russian intellectuals: “Where are we going? What will happen? What’s to be done?”

A significant number of diary entries are devoted to Chernyaev’s conflict with Oleg Rakhmanin, the conservative deputy head of the CC department for relations with ruling Communist parties (known simply by the Russian word for department – Otdel), who tried to push a strong anti-Chinese line in Soviet foreign policy even after Brezhnev himself spoke in favor of improving relations with Beijing in his Tashkent speech. In another glimpse of future new thinking, Chernyaev pushes hard against the anti-Chinese stance, and eventually the “Tashkent line” prevails.

During this period, Brezhnev continues to decline and almost dies in an accident at a factory in Tashkent, from which he had to be “transported off the plane,” because “he could not stand on his feet.” Chernyaev describes Brezhnev’s visit to Baku, Azerbaijan, where he was unable to read a speech printed with “inch-size” font. He notes that other Politburo members, like Arvids Pelshe and Andrey Kirilenko, have not been seen for a long time either. He writes in his diary: “Here's what I think: if Andropov replaces Brezhnev, change may come. If Chernenko replaces Brezhnev, change is unlikely.” As everybody anticipates the death of the top leader, Chernyaev’s mind is preoccupied with Andropov. He notes his presentations at the Secretariat, his new style of chairing meetings, and his “prone[ness] to reflection.”

When Brezhnev finally dies on November 10, Chernyaev writes in his diary a “program” for Andropov, whom he expects to become the successor. The program consists of 15 points and includes practically all the items that would eventually be included in Gorbachev’s program less than three years later, such as getting out of Afghanistan, removing SS-20 missiles from Europe and curbing the military-industrial complex. It turns out that Georgy Arbatov, the omnipresent adviser to Soviet leaders and head of the Institute for U.S. and Canada Studies, has also prepared a similar “program” for the new leader.

The year culminates with the celebration of the 60th anniversary of the USSR, with delegations of 140 countries gathering in Moscow. Chernyaev was busy working with the delegations, including with the Communist Party of the USA, and oversaw publications of various speeches in Pravda. He saw real signs of change in Andropov’s report and noted the air of hope in the meeting hall: “Everyone is expecting major changes from us, something the entire world would notice, changes that would eclipse Afghanistan, and Poland, that would make everyone forget the “Brezhneviada” created in the West (about the use of power for self-enrichment, nepotism – relatives everywhere, about irrepressible boasting, demonstratively showcasing senility as wisdom, corruption, and so forth).”

In his own postscript, Chernayev calls the year 1982 “the runup to perestroika.” A reader of this year’s installment might observe the gradual formation of the unofficial group, or rather network, of people who in three years will form the core of Gorbachev’s “brain trust,” who in this momentous year are tentatively probing each other and finding agreement on the main outlines of change that the country needed desperately.

The Document

Donated by A.S. Chernyaev to The National Security Archive

Translated by Anna Melyakova