Washington, D.C., December 10, 2018 – The National Security Archive mourns the passing of Lyudmila Mikhailovna Alexeyeva, our dear friend, colleague and inspiration for all our work documenting human rights abuses globally. She passed away on December 8 at the age of 91.

The self-described “Grandmother” of Russian human rights, Lyudmila Mikhailovna was a fearless opponent of authoritarianism in her homeland, facing the constant threat of retribution from her early days as a protestor and publisher of samizdat in the Soviet 1960s to her years as an internationally recognized advocate for civil rights in Russia of the 2000s. Sent into exile in the 1970s, she wrote one of the seminal histories of Soviet dissent, reflecting another of her remarkable qualities. (Being a historian, she said, became a “personal harbor” during her enforced time abroad.)

Returning home for good after the collapse of the USSR, she continued to be active, contending alternately with brutal denigration via Russia’s state media and personal flattery from Vladimir Putin himself (who dropped by on her 90th birthday). She was physically assaulted at the age of 82 while visiting a memorial to victims of a terrorist attack. Yet throughout, she kept her commitment to the cause, most recently seeking the best means to cope with the government’s expanding suppression of NGOs, such as the legendary Moscow Helsinki Group, which she helped to found and lead for so many years.

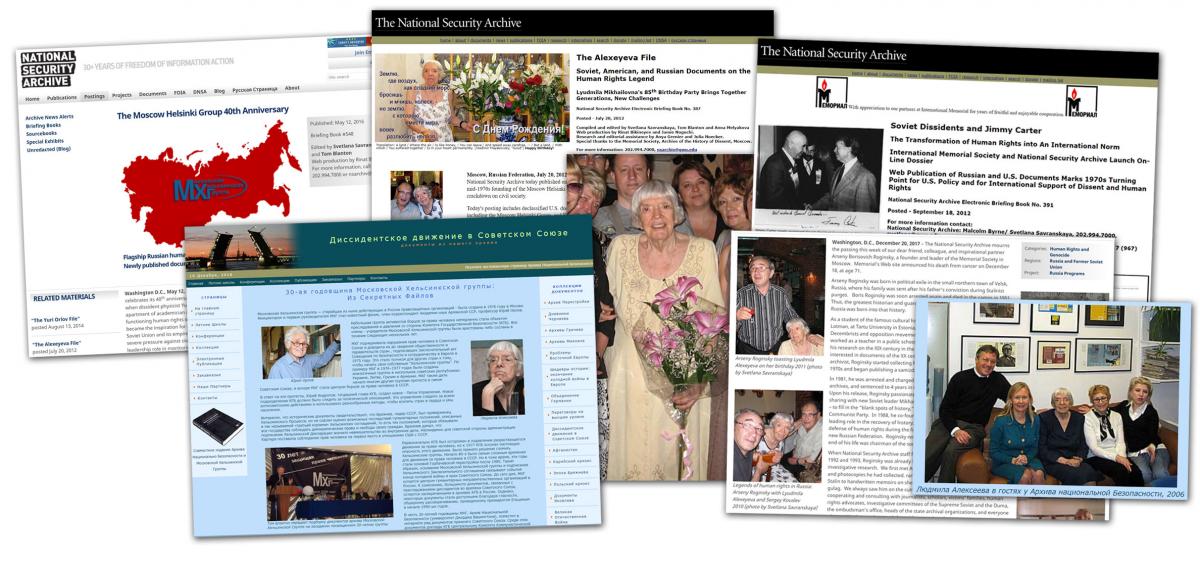

The following brief biography and selection of documents reflect parts of Lyudmila Mikhailovna’s extraordinary life. The National Security Archive first posted these and other items in honor of her 85th birthday.

Biography

Lyudmila Mikhailovna Alexeyeva was born on July 20, 1927 in Yevpatoria, a Black Sea port town in the Crimea (now in Ukraine). Her parents came from modest backgrounds, but both received graduate degrees; her father was an economist and her mother a mathematician. She was a teenager in Moscow during the war, and she attributes her decision to come back and live in Russia after more than a decade of emigration to the attachment to her country and her city formed during those hungry and frozen war years. Alexeyeva originally studied to be an archaeologist, entering Moscow State University in 1945, and graduating with a degree in history in 1950. She received her graduate degree from the Moscow Institute of Economics and Statistics in 1956. She married Valentin Alexeyev in 1945 and had two sons, Sergei and Mikhail. Already in the university she began to question the policies of the regime and decided not to go to graduate school in the history of the CPSU, which at the time would have guaranteed a successful career in politics.

She did join the Communist Party, hoping to reform it from the inside, but very soon she became involved in publishing, copying and disseminating samizdat with the very first human rights movements in the USSR. In 1959 through 1962 she worked as an editor in the academic publishing house Nauka of the USSR Academy of Sciences. In 1966, she joined friends and fellow samizdat publishers in protesting the imprisonment and unfair trial of two fellow writers, Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel. For her involvement with the dissident movement, she lost her job as an editor and was expelled from the Party. Later, in 1970, she found an editorial position at the Institute of Information on Social Sciences, where she worked until her forced emigration in 1977. From 1968 to 1972, she worked as a typist for the first dissident periodical in the USSR, The Chronicle of Current Events.

As the 1960s progressed, Alexeyeva became more and more involved in the emerging human rights movement. Her apartment in Moscow became a meeting place and a storage site for samizdat materials. She built up a large network of friends involved in samizdat and other forms of dissent. Many of her friends were harassed by the police and later arrested. She and her close friends developed a tradition of celebrating incarcerated friends' birthdays at their relatives' houses, and they developed a tradition of "toast number two" dedicated to those who were far away. Her apartment was constantly bugged and surveilled by the KGB.

Founding the Moscow Helsinki Group

In the spring of 1976, the physicist Yuri Orlov – by then an experienced dissident surviving only by his connection to the Armenian Academy of Sciences– asked her to meet him in front of the Bolshoi Ballet. These benches infamously served as the primary trysting site in downtown Moscow, thus guaranteeing the two some privacy while they talked. Orlov shared his idea of creating a group that would focus on implementing the human rights protections in the Helsinki Accords – the 1975 Final Act was published in full in Pravda, and the brilliant idea was simply to hold the Soviet government to the promises it had signed and was blatantly violating.

Orlov had the idea, but he needed someone who could make it happen – a typist, an editor, a writer, a historian – Lyudmila Alexeyeva. In May 1976, she became one of the ten founding members of the Moscow Helsinki Group with the formal announcement reported by foreign journalists with some help from Andrei Sakharov, despite KGB disruption efforts. The government started harassment of the group even before it was formally announced, and very quickly, the group became a target for special attention by Yuri Andropov and his organization – the KGB.

Alexeyeva produced (typed, edited, wrote) many early MHG documents. One of her early – and characteristically remarkable – assignments was a fact-finding mission to investigate charges of sexual harassment against a fellow dissident in Lithuania. Several high school boys who would not testify against their teacher were expelled from school. She arranged a meeting with the Lithuanian Minister of Education, who did not know what the Moscow Helsinki Group was but anything from Moscow sounded prestigious enough to command his attention, and convinced him to return the boys to school. It was only when some higher-up called the Minister to explain what the Helsinki Group really was that he reconsidered his decision.

As one of ten original members of the Moscow Helsinki Group, Alexeyeva received even greater scrutiny from the Soviet government, including the KGB. Over the course of 1976, she was under constant surveillance, including phone taps and tails in public. She had her apartment searched by the KGB and many of her samizdat materials confiscated. In early February 1977, KGB agents burst into her apartment searching for Yuri Orlov, saying "We're looking for someone who thinks like you do." A few days later, she and her second husband, the mathematician Nikolai Williams, were forced to leave the Soviet Union under the threat of arrest. Her departure was very painful – she was convinced that she would never be able to return, and her youngest son had to stay behind.

Alexeyeva in Exile

Alexeyeva briefly stopped over in the UK, where she participated in human rights protests, before she eventually settled in northern Virginia, and became the Moscow Helsinki Group spokesperson in the United States. She testified before the U.S. Congressional Helsinki Commission, worked with NGOs such as the International Helsinki Federation, wrote reports on the CSCE conferences in Belgrade, Madrid and Vienna, which she attended, and became actively involved in the issue of political abuse of psychiatry in the USSR.

She soon met her best-friend-to-be, Larisa Silnicky of Radio Liberty (formerly from Odessa and Prague), who had founded the prominent dissident journal Problems of Eastern Europe, with her husband, Frantisek Silnicky. Alexeyeva started working for the journal as an editor in 1981 (initially an unpaid volunteer!). Meanwhile, she returned to her original calling as a historian and wrote the single most important volume on the movements of which she had been such a key participant. Her book, Soviet Dissent: Contemporary Movements for National, Religious and Human Rights, which was published in the United States in 1984 by Wesleyan University Press, remains the indispensable source on Soviet dissent.

The book was not the only evidence of the way Alexeyeva's talents blossomed in an atmosphere where she could engage in serious research without constant fear of searches and arrest. She worked for Voice of America and for Radio Liberty during the 1980s covering a wide range of issues in her broadcasts, especially in the programs "Neformalam o Neformalakh" and "Novye dvizheniya, novye lyudi," which she produced together with Larisa Silnicky. These and other programs that she produced for the RL were based mainly on samizdat materials that she was getting though dissident channels, and taken together they provide a real encyclopedia of developments in Soviet society in the 1980s. The depth and perceptiveness of her analysis are astounding, especially given the fact that she was writing her scripts from Washington. Other U.S. institutions ranging from the State Department to the AFL-CIO Free Trade Union Institute also asked her for analyses of the Gorbachev changes in the USSR, among other subjects. In the late 1980s-early 1990s, she was especially interested in new labor movements in the Soviet Union, hoping that a Solidarity-type organization could emerge to replace the old communist labor unions.

Back in the USSR

The Moscow Helsinki Group had to be disbanded in 1982 after a campaign of persecution that left only three members free within the Soviet Union. When the Group was finally reestablished in 1989 by Larisa Bogoraz, Alexeyeva was quick to rejoin it from afar, and she never stopped speaking out. She had longed to return to Russia, but thought it would never be possible. She first came back to the USSR in May 1990 (after being denied a visa six times previously by the Soviet authorities) with a group of the International Helsinki Federation members to investigate if conditions were appropriate for convening a conference on the "human dimension" of the Helsinki process. She also attended the subsequent November 1991 official CSCE human rights conference in Moscow, where the human righters could see the end of the Soviet Union just weeks away. She was an early supporter of the idea of convening the conference in Moscow – in order to use it as leverage to make the Soviet government fulfill its obligations – while many Western governments and Helsinki groups were skeptical about holding the conference in the Soviet capital.

In 1992-1993 she made numerous trips to Russia, spending more time there than in the United States. She and her husband Nikolai Williams returned to Russia to stay in 1993, where she resumed her constant activism despite having reached retirement age. She became chair of the new Moscow Helsinki Group in 1996, only 20 years after she and Yuri Orlov discussed the idea and first made it happen; and in that spirit, in the 1990s, she facilitated several new human rights groups throughout Russia.

When Vladimir Putin became president in 2000, Lyudmila Alexeyeva agreed to become part of a formal committee that would advise him on the state of human rights in Russia, while continuing her protest activities. The two did not go well together in Putin's mind, and soon she was under as much suspicion as ever. By this time, though, her legacy as a lifelong dissident was so outsized that it was harder to persecute her. Even state-controlled television felt compelled to give her air-time on occasion, and she used her standing as a human rights legend to bring public attention to abuses ranging from the mass atrocities in the Chechen wars to the abominable conditions in Russian prisons.

When the Moscow Helsinki Group celebrated its 30th anniversary in 2006, with Lyudmila Alexeyeva presiding, Yuri Orlov came back from his physics professorship at Cornell University to join her on stage. Also paying tribute were dozens of present and former public officials from the rank of ex-Prime Minister on down, as well the whole range of opposition politicians and non-governmental activists, for whom she served as the unique convenor and den mother.

The Continuing Challenge in Russia

In 2009, Alexeyeva became an organizer of Strategy 31, the campaign to hold peaceful protests on the 31st of every month that has a 31st, in support of Article 31 of the Russian constitution, which guarantees freedom of assembly. Everyone remembers the protest on December 31, 2009, when Lyudmila Alexeyeva went dressed as the Snow Maiden (Snegurochka in the fairy tales) where dozens of other people were also arrested. But when officials realized they had the Lyudmila Alexeyeva in custody, they returned to the bus where she was being held, personally apologized for the inconvenience and offered her immediate release from custody. She refused until all were released. The video and photographs of the authorities arresting the Snow Maiden and then apologizing went viral on the Internet and made broadcast news all over the world. The "31st" protests have ended in arrests multiple times, but that has yet to deter the protesters, who provided a key spark for the mass protests in December 2011.

The darker side of the authorities' attitude was evident in March 2010, when she was assaulted at the Park Kultury metro station where she was paying her respects to the victims of the subway bombings a few days earlier. She had been vilified by the state media so often that the attacker called himself a "Russian patriot" and asserted (correctly, so far) that he would not be charged for his actions.

In 2012, the chauvinistic assault became institutional and government-wide, with a new law proposed by the Putin regime and approved by the Duma, requiring any organization that received support from abroad to register as a "foreign agent" and submit to multiple audits by the authorities. The intent was clearly to stigmatize NGOs like the Moscow Helsinki Group that have international standing and raise money from around the world. Earlier this month, Lyudmila Alexeyeva announced that the Group would not register as a foreign agent and would no longer accept foreign support once the law goes into effect in November 2012.

Other Russian human righters say they are used to being tagged as foreign agents. In fact, humorous signs appeared at the mass protests in late 2011 asking the U.S. Secretary of State, Hillary Rodham Clinton, "Hillary! Where's my check? I never got my money!" So the debate over strategy, over how best to deal with and to push back against the new repression, will likely dominate the conversation at Lyudmila Mikhailovna's 85th birthday party today (July 20). Yet again, when she is one of the few original Soviet dissidents still alive, she is at the center of the storm, committed to freedom in Russia today, and leading the discussion about how to achieve human rights for all.

[The above text was originally posted on July 20, 2012, here. The documents below are a selection from that 85th birthday commemorative posting.]

The Documents

Document 1: Lyudmila Alexeyeva, "Biography," November 1977.

1977-11-00

Source: Memorial Society, Moscow, Archive of History of Dissent, Fond 101, opis 1, Box 2-3-6

This modest biographical note presents Alexeyeva's own summary of her life as of the year she went into exile. She prepared this note as part of her presentation to the International Sakharov Hearing in Rome, Italy, on 26 November 1977, which was the second in a series named after the distinguished Soviet physicist and activist (the first was in Copenhagen in 1975) that brought together scholars, analysts and dissidents in exile to discuss human rights in the Soviet bloc.

Document 2: KGB Memorandum to the CC CPSU, "About the Hostile Actions of the So-called Group for Assistance of Implementation of the Helsinki Agreements in the USSR," 15 November 1976.

1976-11-15

Source: U.S. Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Dmitrii A. Volkogonov Papers, Reel 18, Container 28

The KGB informed the Politburo about the activities of the MHG for the first time six months after its founding. The report gives a brief history of the human rights movement in the USSR as seen from the KGB. Andropov names each founding member of the group and charges the group with efforts to put the Soviet sincerity in implementing the Helsinki Accords in doubt. The document also alleges MHG efforts to receive official recognition from the United States and reports on its connections with the American embassy.

Document 3: Memo from Andropov to CC CPSU, "About Measures to End the Hostile Activity of Members of the So-called “Group for Assistance in the Implementation of the Helsinki Agreements in the USSR," 5 January 1977.

1977-01-05

Source: U.S. Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Dmitrii A. Volkogonov Papers, Reel 18, Container 28

After the two informational reports above, the KGB started to get serious about terminating the activities of the MHG. This report charges that the group was capable of inflicting serious damage to Soviet interests, that in recent months group members have stepped up their subversive activities, especially through the dissemination of samizdat documents (and particularly the MHG reports), undermining Soviet claims to be implementing the Helsinki Final Act. The Procuracy would later develop measures to put an end to these activities.

Document 4: "Dignity or Death: My Phone was Dead and All Night the KGB Waited Silently at My Door," The Daily Mail, London, 22 March 1977, by Lyudmila Alexeyeva and Nicholas Bethell.

1977-03-22

This is one of a series of articles in the Western media printed soon after Lyudmila Alexeyeva's emigration from the USSR. In interviews she described the deteriorating human rights situation in the Soviet Union, including the increased repression and arrests of Helsinki groups members in Russia, Ukraine, Lithuania and Georgia, and called on the West to put pressure on the Soviet government to comply with the Helsinki Accords.

Document 5: Lyudmila Alexeyeva, letter to friends in Moscow, undated, circa Summer 1984.

1984-00-00

Source: Memorial Society, Moscow, Archive of History of Dissent, Fond 101, opis 1, Box 2-3-6

This extraordinary personal letter provides a unique vista of Alexeyeva's life in exile and her thinking about dissent. Here she describes how she found her calling as a historian (a "personal harbor" which is essential for enduring exile), came to write the book on Soviet dissent, and struggled to reform the radios (Liberty, Free Europe, Voice of America) against the nationalist-authoritarian messages provided from "Vermont and Paris" - meaning Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Vladimir Bukovsky, respectively - or, the Bolsheviks versus her own Mensheviks within the dissident movement, in her striking analogy. Also here are the personal details, the open window in the woods for the cats, the ruminations on the very process of writing letters (like cleaning house, do it regularly and it comes easily, otherwise it's never done or only with great difficulty). Here she pleads for activation as opposed to liquidation of the Helsinki Groups, because "we have nothing else to replace them."

Document 6: The Moscow Helsinki Watch Group [Excerpt from Lyudmila Alexeyeva's book Soviet Dissent (Wesleyan University Press, 1984)

1984-00-00

Source: Soviet Dissent (Wesleyan University Press, 1984)

This account of the founding and the history of the Moscow Helsinki Group comes from a most authoritative source. Lyudmila Alexeyeva included it in her seminal analysis of dissent in the USSR. The chapter shows how the Moscow Helsinki Group became the model and connective tissue for all other human rights groups in the Soviet Union. At the time of writing, she had been forced into exile in the United States.