Washington, D.C., July 22, 2016 - U.S. atomic tests in Bikini Atoll in July 1946 staged by a joint Army-Navy task force were the first atomic explosions since the bombings of Japan a year earlier. Documents posted today by the National Security Archive about “Operation Crossroads” shed light on these events as do galleries of declassified videos and photographs. Of two tests staged to determine the effects of the new weapons on warships, the “Baker” test was the most dangerous by contaminating nearby test ships with radioactive mist. According to the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s Evaluation Board, because of the radioactive water spewed from the lagoon, the “contaminated ships became radioactive stoves, and would have burned all living things aboard with invisible and painless but deadly radiation.”

The Baker test caused a radiological crisis because task force personnel were assigned to do salvage work on contaminated test ships. Stafford Warren, the task force’s radiation safety adviser, warned task force chief Admiral William Blandy of the danger of these activities: the “ships were “extensively contaminated with dangerous amounts of radioactivity.” It was not possible to achieve “quick decontamination without exposing personnel seriously to radiation.” These warnings eventually led Blandy to halt decontamination activities although only after many military and civilian personnel had been exposed to radioactive substances.

Observers from the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission, including two from the Soviet Union, viewed the Crossroads tests from a safe distance. Recently declassified documents shed light on the emerging Cold War atmosphere; one of the observers, Simon Peter Alexandrov, who was in charge of uranium for the Soviet nuclear project, told a U.S. scientist that the purpose of the Bikini test was “to frighten the Soviets,” but they were “not afraid,” and that the Soviet Union had “wonderful planes” which could easily bomb U.S. cities.

The U.S. Navy’s early March 1946 removal of 167 Pacific islanders from Bikini, their ancestral home, so that the Navy and the Army could prepare for the tests, is also documented with film footage. The Bikinians received the impression that the relocation would be temporary, but subsequent nuclear testing in the atoll rendered the islands virtually uninhabitable.

Operation Crossroads 70 Years Later

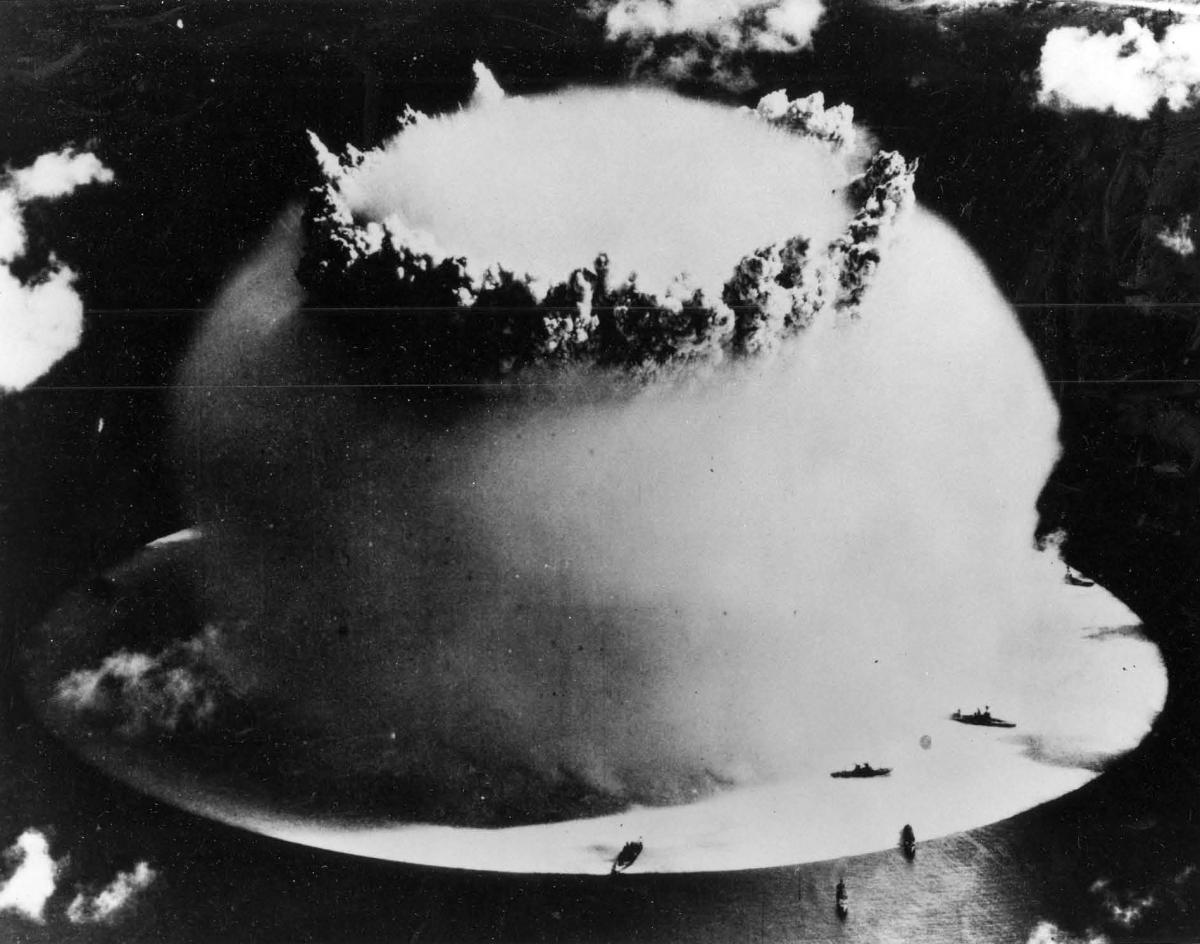

Seventy years ago this month a joint U.S Army-Navy task force staged two atomic weapons tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands, the first atomic explosions since the bombings of Japan in August 1945. The first test, Able, took place on 1 July 1946. The second test, Baker, on 25 July 1946, was the most dangerous, contaminating nearby ships with radioactive fallout and producing iconic images of nuclear explosions later used in Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove. Documents posted today by the National Security Archive, shed light on Operation Crossroads, as does a gallery of videos and photographs.

The Navy, worried about its survival in an atomic war, sought the Bikini tests in order to measure the effects of atomic explosions on warships and other military targets. Named Operation Crossroads by the task force’s director, Rear Admiral William Blandy, the tests involved a fleet of 96 target ships, including captured Japanese and German warships. Both tests gave the U.S. military what it sought: more immediate knowledge of the deadly effects of nuclear weapons.

The U.S. Navy’s early March 1946 removal of 167 Pacific islanders from Bikini, their ancestral home, so that the Navy and the Army could prepare for the tests, is also documented with film footage. The Bikinians received the impression that the relocation would be temporary, but subsequent nuclear testing in the atoll rendered the islands virtually uninhabitable.

Observers from the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission, including two from the Soviet Union, viewed the Crossroads tests from a safe distance. Recently declassified documents shed light on the emerging Cold War atmosphere; one of the observers, Simon Peter Alexandrov, who was in charge of uranium for the Soviet nuclear project, told a U.S. scientist, Paul S. Galtsoff, that while the purpose of the Bikini test was “to frighten the Soviets,” they were “not afraid,” and that the Soviet Union had “wonderful planes” which could easily bomb U.S. cities.

Today’s posting contains a number of primary source documents on the planning of Operation Crossroads and assessments of the two tests, including:

- An estimate from Los Alamos Laboratory of the planned underwater atomic test: “There will probably be enough plutonium near the surface to poison the combined armed forces of the United States at their highest wartime strength.”

- A report by an Army officer on the Able test, which exploded in mid-air above an array of warships, conveyed Army-Navy tensions: Noting that Admiral Blandy had painted a “very optimistic picture from the Navy point of view” of the damage done to the ships, “when we examined the target fleet through our field glasses [we saw] that even on the major capital ship, superstructures had been severely damaged.” “The target fleet had indeed suffered a staggering blow.”

- The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) Evaluation Board noted in a message sent after the Baker test that because of the radioactive water the Baker test spewed upon the ships, the “contaminated ships became radioactive stoves, and would have burned all living things aboard with invisible and painless but deadly radiation.”

- According to a Navy observer’s report, the two tests were “spectacular and awe-inspiring,” but the “radiological contamination of the target vessels which followed the underwater burst was the most startling and threatening aspect.”

- The contamination of the target ships caused by the Baker test led Stafford Warren, the task force’s radiation safety adviser, to warn Admiral Blandy of the danger of continuing decontamination work to salvage the ships: the ships were “in the main extensively contaminated with dangerous amounts of radioactivity.” It was not possible to achieve “quick decontamination without exposing personnel seriously to radiation.” These warnings eventually led Blandy to halt the cleanup effort.

- The Joint Chiefs of Staff Evaluation Board’s final report on the Crossroads tests called for U.S. superiority in atomic weaponry and Congressional action to give the U.S. Presidents license to wage preventive war against adversaries which were acquiring nuclear weapons. The Crossroads report was suppressed for years until it was declassified in 1975.

Planning the First Post-War Atomic Tests

Beginning in late August 1945, shortly after Japan’s surrender, Army Air Force leaders proposed to the U.S. Navy that captured Japanese warships be sunk with atomic bombs. Convinced that air power had decisively defeated Germany and Japan, they believed that naval forces were becoming outmoded. Navy leaders saw a potential threat to their survival but nevertheless believed that warship technology could adjust to a new environment: “ships were not excessively vulnerable to atomic attack” and aircraft carriers were “just as useful as valuable as Air Force bombers for the delivery of atomic weapons.” In October 1945, the Navy responded positively to the Air Force proposals and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest J. King suggested to the Joint Chiefs of Staff aerial and underwater atomic tests against captured Axis ships and surplus U.S. warships.[1]

By January 1945 President Harry S. Truman had approved a Joint Chiefs of Staff plan for one aerial and two underwater tests as well as a Joint Task Force to conduct them. To stage the tests the Navy sought a remote site under U.S. control where it could assemble ships and atomic explosions that would not endanger large populations. By December 1945, Navy planners had decided that the most suitable location was Bikini Atoll, part of the Marshall Islands group, which had been captured from the Japanese in early 1944. The atoll’s people were descendants of communities that had lived there for thousands of years, subsisting on coconuts and seafood. In order for Admiral Blandy’s task force to prepare for Crossroads, the Navy began to take over the atoll. In February 1946, Commodore Ben Wyatt, the Marshall Island’s military governor, informed the Bikinians that they must leave so that the U.S. government could conduct military tests “for the good of mankind.” On 7 March1946 the Navy transported the Bikinians to Rongerik Island where, as it turned out, food and water were in short supply.

Over 42,000 U.S. military and civilian personnel, of whom 38,000 were naval personnel, participated in preparations and activities relating to Crossroads. The task force included eight task groups with such responsibilities as communications and electronics, photography, instrumentation, safety/security, and the inspection of target ships, among others. Fifteen universities were involved and so were many corporations and nongovernmental organizations. Part of the work included deploying military equipment to be exposed to the tests (the Army alone had 3,000 personnel assigned to measure damage to army equipment exposed to the explosion). The fleet of target ships included 94 aircraft carriers, battleships, cruisers, destroyers, submarines, and landing craft, among other ships. Some of the vessels had been declared excess inventory after the Navy had scaled down its forces, and others had been damaged during World War II. Three German and Japanese warships captured during the war were among the ships to be targeted. The large number of personnel involved and the costs of maintaining the ships made Crossroads the most expensive nuclear test series in history, about $2.2 billion in 2016 dollars.[2]

Stressing the “defensive” aspects of Crossroads, the Navy organized a massive publicity campaign that influenced media and radio coverage for months. Public criticism then emerged, domestically and internationally, leading to an intensified public relations effort.

Although the Cold War had not yet begun, U.S.-Soviet relations were uneasy, and U.S. critics expressed concern that a “grandiose display of atomic power” (Sen. Scott Lucas, D-Ill.) would increase international tensions. Moreover, the first test, scheduled for 15 May, would send the wrong signal when Washington was involved in United Nations discussions over international control of atomic energy. Some opponents worried about a waste of resources while plans to expose test animals to radioactivity generated protest letters from members of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Skeptical scientists argued that the tests would produce no new information and in a letter to President Truman, former Manhattan Project director J. Robert Oppenheimer argued that mathematical calculations and model tests would produce better data. In light of the conflict with the U.N. discussions, President Truman ordered the first test to be postponed until 1 July.

Some senior advisers to the U.S. government believed that the atomic tests were diplomatically useful. In a discussion at the Council on Foreign Relations, Harvard University president James B. Conant, who had served as wartime chairman of the National Defense Research Committee during World War II, argued that the “Russians are more likely … to come to an effective agreement for the control of atomic energy if we keep our strength and continue to produce atomic bombs.” Truman administration officials may well have seen the tests as bolstering the U.S. position in negotiations with Moscow; certainly, senior U.S. military officials at the time believed the bomb was vital to maintaining “a position of paramount military power” and possibly a “crucial factor in our effort to achieve first a stabilized condition and eventually a lasting peace.”[3]

To support the message that the tests were for defensive purpose, the Truman administration invited journalists and international observers to view the atomic detonations from safe distances. The latter consisted of two representatives each from countries belonging to the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission (UNAEC)--Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Egypt, France, Mexico, the Netherlands, Poland, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union--which were then discussing the plans for international control of atomic weapons. The U.N. observers and U.S. government officials would sail on the U.S.S. Panamint, in a voyage which lasted several months. With at least one U.S. intelligence officer on the ship, the observers, especially the two from the Soviet Union, were likely targets of U.S. efforts to collect intelligence information on the Soviet atomic program.

The Able and Baker Tests

The first test, Able on 1 July 1946, involved an air burst directly above the target ships. “Dave’s Dream,” a B-29 Superfortress which carried out the initial test run for Able, dropped a “Fat Man” plutonium bomb (the type dropped on Nagasaki), with an explosive yield of 23 kilotons. In an error which has never been fully explained, the bomb missed its target by several thousand feet, inadvertently destroying one of the ships carrying measuring instruments. The error created a storm of criticism. The blast did not destroy large numbers of target ships, but five sank and some 40 others were damaged, many of them rendered useless, a “staggering blow” according to an Army officer with the Manhattan Project. Yet media representatives, on ships 20 miles from the test and too far away to experience Able’s shock waves, expressed disappointment, treating it as a virtual dud.[4] By contrast, in a top secret report written a few weeks after Able, the JCS Evaluation Board wrote that all personnel on ships within a mile of the detonation would have been killed by gamma rays and neutrons produced by the “initial flash.”

The Crossroads tests were the subject of intense media coverage and dominated the front pages with scores of journalists from the U.S. and overseas covering the Able test (somewhat fewer attended the second test). Members of Congress also attended, as did a cabinet member (Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal) and the representatives from the UNAEC. Even though basic information about atomic weapons (e.g., production, design, yield, and effects) was highly classified, as was information about the results of the tests, according to the Manhattan Project’s report on Crossroads, "it has been truly said that the operation was ‘the most observed, most photographed, most talked-of scientific test ever conducted.’ Paradoxically, it may also be said that it was the most publicly advertised secret test ever conducted."[5]

The second test, Baker, on 25 July 1946, an underwater nuclear detonation, was, according to the Task Force history, “a giant and unprecedented spectacle.” It produced a huge column of a million tons of water over a mile high, and 80 to 100 waves spread radioactive fallout on nearby ships, partly through rain and partly through a “moving column of radioactive mist.”[6] The column of water lifted the battleship Arkansas before plunging it into the lagoon. Nine ships eventually sank, including another battleship and an aircraft carrier. But the most serious damage was unseen. According to the initial report by the JCS Evaluation Board, the radioactive hazard produced by the spread of water was so dangerous that “after 4 days it was still unsafe for inspection parties operating within a well-established safety margin, to spend any useful length of time at the center of the target area or to board ships anchored there.” Of the test animals in the target ships, all of the pigs died within a month. Even though military experts had predicted the spread of radioactivity months before, its intensity came as a surprise.[7]

Post-Baker Radiation Crisis

Within a few days of Baker, the Joint Task Force initiated decontamination efforts to salvage the target ships for future use, including the scheduled third test, Charlie. However, Stafford Warren, the task force’s radiological safety adviser, was concerned about excessive contamination and insufficient monitors to keep track of radiation hazards. Warren saw a variety of risks: contamination of work clothing and gear bringing the radioactive hazard back to the support ships, radioactivity in the seawater, and the concentration of radioactivity in marine life, such as algae. Especially worrisome to Warren was beta radiation (which can travel short distances in the air and penetrate human skin), and what he saw as growing evidence that the ships were heavily contaminated by alpha-emitters produced by plutonium particles, “the most poisonous chemical known.” Under these circumstances Warren repeatedly pressed a reluctant Admiral Blandy to halt the decontamination efforts and remove personnel from the lagoon. Blandy and the Navy officers were slow to this advice because they did not grasp that the radiation threat could be dangerous even if ship decks were spotless. Nevertheless, Warren persisted and by 10 August a reluctant Blandy ordered a halt to the contamination effort; soon, thousands of task force personnel were leaving Bikini. While the Able test had physically damaged or destroyed ships, the Baker test showed that radioactivity could disable a fleet.

Warren was later criticized for being excessively cautious and pessimistic about the radiation hazard from the decontamination effort, but at the time task force radiation monitors wondered about the long-term impact of the exposure. A few weeks after Baker, one of the radiation monitors, William Myers, wrote to Warren that he did not believe that anyone sustained any “permanent” injury from Baker. Yet he was concerned about the long-run impact because “many of us probably received much more penetrating, ionizing radiation than instruments of very low beta-sensitivity were able to record.” Myers was raising a question that concerned senior officials, such as General Leslie Groves, who worried that Crossroads veterans would make legal claims against the government for injuries caused by radiation exposure. No meaningful attempts were made to identify those who experienced damaging internal exposure, but during the years that followed, some veterans became cancer victims and sought compensation from the federal government. Few got anywhere with their claims until 1988 when Congress passed legislation eliminating the need to prove their exposure.[8]

While Blandy was making decisions about the radiation crisis caused by the Baker test, he was also planning for the deep underwater test, Charlie, scheduled for April 1947. At the same time, however, senior officials in the Manhattan Project and the Pentagon were calling for cancellation of the third test on the grounds that it had had no military value; even more important, making another bomb available for the test would detract from the efforts of Los Alamos Laboratory to design and produce a lighter and smaller atomic weapon. The Joint Chiefs of Staff accepted the case against Charlie and agreed to indefinitely postpone it.

Over a year after Crossroads, the Joint Chiefs of Staff Evaluation Board, chaired by MIT President Karl Compton, completed its top secret report on the tests. Highly controversial, the report was not declassified until 1975, even though some of the board members urged public release of an excised version. By the time the report was finished, the Cold War was ongoing and the recommendations for maintaining nuclear superiority were consistent with the new foreign policy climate. Yet the discussions of the effects of nuclear war were unsettling: according to the report, the use of atomic weapons and other weapons of mass destruction, such as biological warfare, would make it “quite possible to depopulate vast areas of the earth's surface, leaving only vestigial remnants of man's material works.” But proposals that Congress give the President authority to wage preventive war against other nations that were developing nuclear weapons capabilities were especially contentious. In the end secrecy prevailed: the State Department and the Defense Department did not want detailed discussions of atomic warfare and weapons effects to be in the public domain, and unveiling preventive war arguments was diplomatically impossible.

The people of Bikini Atoll had the impression that they would be able to return sometime after the tests, but they never could, and the Bikinians’ malnutrition as a result of their Rongerik resettlement was bad press for the Navy. After a temporary move to Kwajalein, they settled in Kili Island, 400 miles south of Bikini. That settlement was also unsatisfactory but Bikini became uninhabitable because of massive contamination caused by the 1954 Castle Bravo test. A U.S. government effort to relocate the Bikinians back to their home atoll in the late 1960s proved disastrous because U.S. officials had seriously underestimated how much contaminated coconut the Bikinians would be consuming. In 1978, Washington relocated the Bikinians, mostly toKili Island where it has been difficult to sustain traditional ways of life. Several lawsuits during the 1980s led to a $75 million settlement and the creation of a $110 million trust for environmental cleanup and resettlement of the Bikinians. Today, few people live on the atoll, which has become a UNESCO World Heritage site, but climate change threatens its existence.

Documents

Document 01

RG 218, Joint Chiefs of Staff, Central Decimal Files, 1948-1950, box 231, CCS 476.1 (10-16-1945), Section 9.

The Air Force had already proposed using captured Japanese warships in atomic weapons tests, and CNO King responded favorably. Convinced that the threat of atomic warfare had important implications for the "size and nature" of the Army and Navy, he recommended a number of atomic tests to determine their effects on "current design" and a follow-up test to "determine the effectiveness of design changes resulting therefrom." The latter was not held, but the "primary facts which must be determined are the effects of atomic bombs exploded in the air or underwater on hulls, material, and personnel." To do so, King recommended the use of surplus ships and one of the Caroline Islands as a possible test site. Owing to the wide public interests in atomic weapons, he suggested a policy of tight secrecy to prevent the release of "details."

Document 02

Record Group 77, Records of Office of the Chief of Engineers, Records of the Office of the Commanding General: Manhattan Project [RG 77], Operation Crossroads December 1945-September 1946, box 4, folder 8.

With an underwater atomic test under discussion in the fall of 1945, Manhattan Project weapons experts advised against it because it would involve "so many major hazards." The central problem was that "approximately fifty percent of the radioactive fission products released by an atomic bomb would end up in the ocean in the immediate vicinity of the point of detonation." For example, a radioactive spray would "cover a large surrounding area which would be heavily contaminated." Moreover, the "ships themselves would be contaminated through their hulls," and fish life in a "large area would be damaged."

Document 03

Nuclear Testing Archive/National Security Technologies [Department of Energy contractor] [hereinafter cited as NTA, with document number], NV0120851.

In a memo to Norris Bradbury, who succeeded J. Robert Oppenheimer as director of Los Alamos laboratory, Henry Newson, a group leader at the lab, raised more warnings about atomic weapons tests in an oceanic environment. According to Newson, "the water near a recent surface explosion will be a witch's brew, and this will be true to a lesser extent for the other tests. There will probably be enough plutonium near the surface to poison the combined armed forces of the United States at their highest wartime strength."

Document 04

National Archives, Record Group 341, U.S. Air Force Headquarters, Air Force Plans Decimal Files 1942-1954, box 448.384.3 (17 August 1945) Atomic Section 1.

In light of the Navy and the Army Air Force's interest in staging atomic tests against warships and other combatant vessels, Truman approved a statement by the War Department and the Navy Department that joint Army-Navy tests would be conducted to "determine the effect of the atomic bomb against naval vessels." The next step was to prepare for Truman's approval of a plan for the tests and issue a presidential directive to the "implementing agency," which the Joint Staff had drafted. According to the JCS proposal, a joint task force reporting to the Chiefs would carry out the tests while an evaluation board would appraise them for the Joint Chiefs. The task force director would be a Navy flag officer with "extensive operational experience."

In order of priority, the three proposed tests would detonate a bomb 1) in the air against "ships of various types," 2) at the surface of the water or "underwater at a moderate depth", and 3) at several thousand feet below the surface. For example, an air test would help determine the "range at which targets ... are rendered militarily ineffective by blast from detonation" as the range at which fission products "preclude [the] operation of ships." Moreover, the tests could help gauge the effects of atomic weapons on such targets as "personnel, to include blast, burn and radiation hazards and effects."

Document 05

RG 218, Joint Chiefs of Staff, Central Decimal Files, 1948-1950, box 231, CCS 476.1 (10-16-1945), Section 9.

The Chiefs recommended to Secretary of War Robert Patterson and Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal that they sign off on the attached memorandum advising President Truman to approve the tests and the proposal for a task force. The tests were "necessary" not only to study the impact of an atomic explosion on ships but to "determine ... the consequences of this powerful aerial weapon with respect to the size, composition and employment of the armed forces." The Joint Chiefs believed that the tests could "best be conducted by a joint task force operating under their direction and with the support of the War and Navy Departments including the Manhattan District." Forrestal and Acting Secretary of War Kenneth Royall sent their recommendations to Truman on 8 January, and the President approved them two days later.

Document 06

RG 77, Operation Crossroads December 1945-September 1946, box 28 [Navy cables January-February 1946]

In a message to the Pacific Fleet's commander, Commodore Ben Wyatt wrote of constructions plans on the atoll in preparation for the arrival of Joint Task Force One, as well as of plans to move the Bikinians to Rongerik. In an upbeat account of the request that Juda and the Bikinians leave the atoll, Wyatt described their response as an immediate one with Juda saying that they were "proud ... to be part of this wonderful undertaking" and how "happy" they were to move elsewhere. In a version which he gave some years later, however, Wyatt said that the Bikinians had a meeting after which Juda conveyed the decision. Various considerations probably shaped their acquiescence, including gratitude to the Americans for defeating the Japanese occupiers and for providing food and other aid, but also a sense of vulnerability. One of the Bikinians involved later said that "we didn't feel we had any other choice but to obey the Americans."[9]

Document 07

UCLA Library Special Collections, Stafford Leak Warren Papers, 1917-1980, box 74, folder 6.

In the opening months of 1946, Operation Crossroads was the subject of significant media coverage. This report by Navy public relations specialist Captain Fitzhugh Lee reviewed the problems raised by the coverage and public criticisms of the Crossroads tests. For the most part he found that the reporting was "sane and encouraging," but, as he noted, some critics argued that the tests were "dangerous or ill advised." Among the criticisms were that the tests were "unscientific," expressions of inter-service rivalries, destructive to sea life and fisheries, liable to cause dangerous phenomena such as tidal waves or radioactive risk to military personnel, cruel to the tested animals, and potentially damaging to international relations. As Weisgall noted in his book, Lee's suggested talking points were not entirely consistent, for example, the tests were "scientific experiments" but were necessary to familiarize the military with the use of atomic weapons.

Document 08

RG 59, Records of the Department of State, Records of the Special Assistant to the Secretary for Atomic Energy and Outer Space, General Records Relating to Atomic Energy Matters, 1948-1962, box 37, 16. U.S. Government 11 Navy Test 1946-1952.

On a Saturday morning in late March 1946, Admiral William Blandy, the Joint Task Force's director, briefed the President's Evaluation Commission, composed of civilians, on the plans for the atomic tests at Bikini, including the reasons why Bikini itself had been selected (see section 8 of report). At this point, former Los Alamos laboratory director J. Robert Oppenheimer was a member of the commission but he would soon drop out (see document 9 below). During the discussion, Oppenheimer asked whether a "model test" could provide the same information as an actual weapons test, but Admiral Parsons and others suggested that such tests could not duplicate ships'structures, among other considerations.

During the discussion Blandy explained why target ships in the lagoon would be clustered close together: "1) the effect of the blast pressure drops off rather quickly with distance and 2) that it is desired to allow for possible bombing errors, and insure that the bomb will burst near at least one large ship." The latter point was a prescient one in light of the significant and expensive bombing error that would occur during the first test.

Document 09

National Archives, Records of the Bureau of Ships, Record Group 19 (RG 19), Records Relating to Operation "Crossroads," box 5, A9 Reports.

Concerned about the criticism of and opposition to the Crossroads tests, Blandy advised Task Force One members on how they should spin any public statements about the tests. Blandy advised his somewhat disingenuously staff that the "the general public must not obtain the erroneous impression that the sole purpose of the tests is to determine the effects of atomic explosives against naval vessels." The Joint Staff paper reproduced above indicates that the tests had a number of objectives, but the Navy would not have been motivated to promote the tests had it not been for the interest in the vulnerability of the fleet to atomic weapons.

Document 10

RG 59, Records of the Department of State, Records of the Special Assistant to the Secretary for Atomic Energy and Outer Space, General Records Relating to Atomic Energy Matters, 1948-1962, box 37, 16. U. S. Government 11. Navy Test 1946-1952.

The meeting with Blandy's task force had raised more questions in Oppenheimer's mind and he wrote to President Truman about his misgivings. As before, he believed that model tests would provide valuable information about the effects of the bomb, but so would "simple laboratory methods." Among his other concerns was that there was some chance of a dud because the "Fat Man" weapons had a design problem, yet the Navy had rejected recommendations to use a better version. Moreover, the tests focused on a "trivial" problem because the "overwhelming effectiveness of atomic weapons lies in their use for the bombardment of cities, and of centers of production and population." A few days later, Oppenheimer resigned from the Presidential Review Commission, although it took several months before the White House announced the resignation. Truman did not take well to the critique; apparently Oppenheimer had already antagonized Truman during an October 1945 meeting; according to a note which Truman sent to Under Secretary of State Dean Acheson, the "cry-baby scientist" had "spent much of his time wringing his hands and telling me they had blood on them."[10]

Document 11

UCLA Library Special Collections, Stafford Leak Warren Papers, 1917-1980, box 73, folder 13.

During the weeks before Crossroads, Navy officials were making plans to deal with post-test contamination. Owing to the danger of radioactive contamination of sea water in the lagoon, a Bureau of Ships conference directed that no distilling plants for the production of water used on board or other apparatus on the ships using sea water would be operated after the tests until the water had been deemed safe.

Document 12

RG 59, Records of the Department of State, Records of the Special Assistant to the Secretary for Atomic Energy and Outer Space, General Records Relating to Atomic Energy Matters, 1948-1962, box 37, 16. U. S. Government 11. Navy Test 1946-1952.

The recently organized Federation of American Scientists, representing a large number of Los Alamos scientists, had set up an office in Washington, D.C. and issued one of its earliest public statements in opposition to the Bikini tests. Disputing official statements that the tests were being held to produce scientific information, the Federation argued that "The tests are purely military, not scientific." Moreover, "Scientists expect nothing of scientific value, and little of technical value to peacetime uses of atomic energy, as a result of these tests." While scientists were not in a position to evaluate the military worth of the tests, they could raise issues which journalists and newspaper readers needed to take into account. For example, the "number of ships destroyed will not be the best standard for judging the effect of the bomb." Because the radius of "total destruction" was only about one square mile perhaps only one or two ships would be sunk. That would hardly compare to the level of destruction to a U.S. city

Noting the possibility that the weapon could fail, the Federation argued that the Navy should announce the "actual strengths" of the bomb detonated at Bikini because "the actual bomb used may not explode as efficiently as did the bomb at Nagasaki." If tests were to occur, the Federation believed that a deep underwater test would have the great value because it "is potentially far more dangerous to an entire fleet." It could create "sort of monstrous bubble of energy, which might buckle the plates of ships several miles distant."

Document 13

UCLA Library Special Collections, Stafford Leak Warren Papers, 1917-1980, box 74, folder 1.

Head of the British delegation to the Manhattan Project, William Penney, was a central figure at Los Alamos (he later led the British secret atomic bomb project). Like others, Penney recognized that an underwater test would cause serious environmental contamination; he estimated that it would produce a water column of about 8,000 feet in height. Its collapse and the "strong turbulence developed will certainly cover many ships with water and contaminate them."

Document 14

RG 218, Central Decimal Files, 1948-1950, box 231, CCS 476.1 (10-16-1945), Section 8.

Commending the Joint Task Force for its "excellent performance," the Evaluation Board noted that the detonation was off course by 1500 to 2000 feet, but did not dwell upon it. The report covered the extensive damage to ships within a half-mile of ground zero, including 4 ships which sank promptly or within a day, a severely damaged submarine, and a "badly wrecked" aircraft carrier, the Independence. In addition, the explosion initiated "numerous fires" on ships, including one which was two miles away from the explosion point. Major combatant ships within a half-mile had "badly wrecked" superstructures to the point they would have been "unquestionably put out of action." Moreover, "within the area of extensive blast damage to ship superstructure, there is evidence that personnel within the ships would have been exposed to a lethal dosage of radiological effects," a point which the Board developed further in a subsequent message.

Document 15

RG 77, Operation Crossroads Records, 12/1945 - 9/1946., box 30, unlabeled file.

Admiral Blandy's report to the Joint Chiefs of Staff provided detailed information about the extent of the damage to the ships caused by Able's blast, radiation, and fire effects. With respect to radiation effects, 90 percent of the test animals survived the explosion but recovered animals would "suffer severe radiation illness and most will die." Not directly admitting that the bomb was off target or that the mistake destroyed important instruments on the U.S.S. Gilliam, Blandy only acknowledged that the "unexpected position of burst" --as well as an error in transmitting timing signals-- had caused the loss of some "records" (e.g. instrumentation data), a loss which was far more significant and costly than indicated.

Document 16

RG 77, Operation Crossroads Records, 12/1945 - 9/1946, box 26, J-2-1 Manhattan Project Observers.

One of General Groves' top aides, Colonel Lyle E. Seeman, was present at Bikini and sent the general his observations taken from the Blue Ridge, 20.4 miles away from ground zero. The military observers gained only a "slight appreciation of the physical phenomena" and the members of the press were "violent in criticism." According to Seeman, "the heat, blast and sound waves were only faintly perceptible, particularly the first two, and then only to an observer knowing approximate time of incidence." Not only did a cloud obscure the "mushroom effect," but "the strong prevailing wind and sun conditions easily obscured the bomb phenomena." Even if the weapon's effects were not palpable at a distance, according to Seeman, the "heat and radiation effects to vessels within 1,000 yards would have been fatal to exposed personnel, and radiation effects would have been extremely serious to other personnel, depending upon their degree of shielding."

Document 17

RG 77, Operation Crossroads Records, 12/1945 - 9/1946, box 26, J-2-1 Manhattan Project Observers.

Colonel Herbert C. Gee, an Army engineer on Groves' staff, filed a report which provided a different perspective on the test itself as well as criticism of the Navy's reactions. Viewing the test with the Manhattan Project observers group on the Cumberland Sound, 20 miles from the test, Gee had no problem in seeing the development of the mushroom cloud: its shape "was exactly that which had been predicted and resembled very closely the clouds which all of us had seen in pictures prior to our departure for Bikini." Noting that Admiral Blandy had painted a "very optimistic picture from the Navy point of view" of the damage done to the ships, "when we examined the target fleet through our field glasses [we saw] that even on the major capital ship, superstructures had been severely damaged." "The target fleet had indeed suffered a staggering blow." Later, Gee wrote that the "attempts made by various Naval officers, including Admiral Blandy in his brief conference with the Manhattan Observer Group, to discount the effects of "the bomb furnished a source of considerable amusement to our entire group. So much emphasis was placed on the fact that the various vessels remained afloat that all of us became convinced that the Navy was indeed grasping at straws in attempting to build up a case for the battleships."

Document 18

Record Group 59, Records of the Department of State, Records of the Special Assistant to the Secretary for Atomic Energy and Outer Space, General Records Relating to Atomic Energy Matters, 1948-1962, box 77, 18. Weapons: 12. Testing: g. Proving Grounds-Bikini-General.

Written after Able and probably before Baker, this unattributed memorandum assesses the 22 foreign observers, members of the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission, who sailed on the U.S.S. Panamint to watch the Crossroads tests. The trip lasted several months and the passengers were cut off from the outside world with few diversions except for nightly motion pictures. The bulk of the report concerns France and the Soviet Union, both of whose national atomic energy programs were of special interest to Washington. With respect to the French, the drafter of this memorandum was interested in the status of the French atomic energy program, including what the observers, Andre Labarthe and Pierre Goldschmidt, had to say about Frederic Joliot-Curie, the French physicist and Nobel Prize winner (1935), and son-in-law of Marie Curie. Apparently Joliot-Curie was "deeply hurt by the statements against him which appeared in the Smyth Report [on the U.S. atomic bomb program]." Because Joliot had done pioneering work on the problem of chain reactions on the eve of World War II, perhaps he believed that the report had unfairly minimized his contribution.[11] According to Goldschmidt, with his active membership in the French Communist Party, Joliot-Curie was "almost obsessed with the idea that people believe that everything he knows he tells to Moscow."

Most of the text concerns the two Soviet observers: the physicist Mikhail G. Mescheryakov and non-ferrous metals mining expert Simon Peter Alexandrov; according to the U.S. observer, both showed, "at all times ... a duplicate of Russian attitude in the United Nations: suspicion, bombast, wounded pride, indignation etc." Mescheryakov refused to volunteer any information, but Alexandrov, within limits, was friendly and talkative: he provided much information on his background, but all he said about the Soviet nuclear project was that uranium was a top secret subject and that his country was making advances in fission research. A follow-up memorandum (see document 29) indicated that Alexandrov was in charge of uranium ore procurement and reported directly to Beria.[12]

On the Baruch plan for international control of atomic energy, the Soviets declared they "would have none of it. When asked what was wrong with it they said simply that it left us in too powerful a position, and when reminded that we had said we would destroy all of our atomic bombs, they answered simply: 'But we don't believe you.'" The problem with the plan, from their perspective (and that of other observers) was that until an international control system was in place, the United States would keep its atomic monopoly.[13]

The drafter of this memorandum is unknown but it is likely that the foreign observers, especially the two Soviets, were the targets of a coordinated effort to gather intelligence, possibly conducted by Navy and Army officers. Sailing on the Panamint was an interesting mix of military personnel with intelligence backgrounds, including Colonel Edwin F. Black who had served in the Office of Strategic Services during World War II and then in the post-war Strategic Services Unit (SSU), and Captain John L. Callan, who had served as naval attache in Rome early in World War II. In the case of Black, his task, as he explained to Allen Dulles at the time, was to “look after” the foreign observers. Also on the Panamint was the head of Dutch Naval intelligence, Captain G. B. Salm, and Australia's naval attache in Washington, Commander S.H.K. Spurgeon.

Document 19

RG 218, Central Decimal Files, 1948-1950, box 231, CCS 476.1 (10-16-1945), Section 9.

In their top secret message to Washington, the Evaluation Board provided more information on the Able test as well as their assessment of Baker. On Able, the Board declared that all ships within a mile of the detonation point would have become "inoperative" because crew would have been killed by gamma rays and neutrons produced by the "initial flash." The coverage on Baker included a detailed account of the Able test, from the huge incandescent dome which rose from the lagoon at the moment of detonation to the resulting 5500 feet high column of war and the "great quantities of radioactive water [which] descended upon the ships" either from the column of water or 80- to 100-foot-high waves. Comparing the two tests, the Evaluation Board noted that because of the radioactive water that Baker spewed upon the ships, the "contaminated ships became radioactive stoves, and would have burned all living things aboard with invisible and painless but deadly radiation." The message concluded that "so long as atomic bombs could be used against this country the Board urges the continued production of atomic material and research and development in all fields related to atomic warfare."

Document 20

RG 77, Operation Crossroads Records, 12/1945 - 9/1946, box 36, Notes on Movies and Stills of Test A.

Possibly a statement prepared for a documentary film on Baker, it included a vivid and detailed account of the physical phenomena produced by the underwater detonation. The commentary emphasized the "intense radioactivity in the waters of the lagoon" that the explosion produced, which included contamination by dangerous fission products. Moreover, the "highly lethal radioactivity" in the water deposited on the ships made it impossible for personnel to board them "for any useful length of time" for four days after the test. Comparing the "radiological phenomenon" produced by the two tests, Major Young suggested that "unprotected personnel" within a mile of Able would have suffered "high casualties" but those surviving immediate effects would not have been menaced by radioactivity persisting after the burst" (compared to Baker). According to this commentary, Baker's explosive yield was of 20 kilotons, although most reports agree that it was in the 23 kiloton range.

Document 21

RG 77, Operation Crossroads Records, 12/1945 - 9/1946, box 26, J-2-1 Manhattan Project Observers.

One of the Manhattan Project's observers, Colonel Austin Wortham "Cy" Betts, wrote a series of letters to his boss, General Kenneth D. Nichols, who was a key figure in the project. A major problem for the Able test was that the bomb missed its target by a half-a-mile thereby destroying scientific measuring devices placed at that site, including the Gilliam, a ship which carried important measuring devices. Moreover, the explosion was too far from other equipment to measure it. According to Betts, photos taken from the bomber showed that the bomb "did not yaw or bob appreciably." Not wanting to acknowledge an error, Brigadier General Thomas Power (later commander-in-Strategic Air Command) told Admiral Parsons that the Army Air Force was "going to use these shots to prove that the plane was in the exactly correct position at the moment of bomb release and that the bomb was a poor one." Power may have been referring to the poor ballistics of the "Fat Man" weapon type used in the Able test, but a more basic problem may have been General Groves' unwillingness to share "complete ballistic information" on "Fat Man."[14]

Document 22

NTA, NV0140495.

Writing to his spouse, Viola, Stafford Warren, the task force's radiological safety adviser, told her about the "dangerous" contamination problem but his spin was rather more positive than it would be in a few days: the "work here is very strenuous & we are pushed for time. The radioactivity is still high & dangerous but we are making some headway in decontamination & slowly cleaning ship by ship." He estimated decontamination would be complete by 14 August. After noting that the fleet had been moved to cleaner waters," Warren acknowledged that the "radioactivity is a more serious thing than they [Blandy and his advisers] tho[ugh]t.[15]" While later studies suggested that Warren's estimate of the danger was overstated and that measuring instruments of the time were deficient, he could only rely on his own judgment and the technology at hand.[16]

Document 23

RG 77, Operation Crossroads Records, 12/1945 - 9/1946, box 26, J-2-1 Manhattan Project Observers.

Betts' second memo to Nichols illustrated the dangers raised by Baker's watery radioactive fallout. Decontamination of surviving target ships was a part of the post-test routine so they could be salvaged, but Betts reported that essential workers could spend no more than a half hour below decks when working aboard the New York and the Pensacola. Generalizing about the contamination problem, Betts observed that "Experience so far seems to indicate that the process of decontamination of very hot vessels is going to be a very long drawn out affair. Those vessels that have been washed several times show that after the first treatment, which usually cuts the activity about fifty percent, very little progress is made with subsequent washings. They do not get real results until they can get the ship cool enough to put a crew aboard that can really scrub things down." How safe that was for the crew Betts did not mention.

Document 24

NTA, NV0140692.

In the days after he wrote his spouse, Stafford Warren became even more disturbed about the radioactivity threat. By 7 August, his review of the potential dangers to personnel exposed to gamma radiation, beta radiation, and alpha emitters led him to conclude that decontamination and survey work had to be brought to an end quickly. Just by living on the lagoon, Warren noted, personnel already had daily exposure of up to 10 percent of the permitted doses of gamma radiation (0.1 roentgen daily was the official standard). For example, with respect to alpha emitters, e.g. plutonium particles, Warren wrote that "detection is a matter of great difficulty but it is insidiously toxic in very minute quantities."[17] Moreover, the most important target ships "had many lethal doses deposited on them and retained in crevices and other places involved in the final cleanup." And measuring the situation was difficult; according to section 4, "Instrument Situation," "relatively few instruments remain in trustworthy condition." Therefore, Warren concluded that because the "target vessels are in the main extensively contaminated with dangerous amounts of radioactivity," it was not possible to achieve "quick decontamination without exposing personnel seriously to radiation." Therefore, "The Task Force finds itself at a period where no further gain can be obtained without great risk of harm to personnel engaged in decontamination and survey work unless such work ceases in the very near future." He recommended that work stop on 15 August.

Document 25

NTA, NV0 064034.

A report from Lieutenant Commander William A. Wulfman underlined the continuing uncertainty and danger: decontamination "work on target ships has increased to the point that it is impossible to provide adequate protection for the personnel involved in this work." Of six monitors assigned to the USS Salt Lake City, four had been overexposed to radiation.

Document 26

RG 77, Operation Crossroads Records, 12/1945 - 9/1946, box 26, J-2-1 Manhattan Project Observers.

As Betts reported, Admiral Blandy accepted some of Warren's advice by agreeing to a "serious slowing down of activity," but he would not agree to close down decontamination altogether. Decontamination work would continue "no matter how long it may take." Admiral Thorvald A. Solberg, Blandy's deputy, ordered an effort to recover measuring instruments and to continue decontamination work on 10 ships which were needed as targets for the third test. Betts noted that his memo was classified secret because the "toughest part of test Baker" was the contamination problem.

Document 27

NTA, NV0048661.

Blandy moved more decisively a few days later. He recommended to the Chief of Naval Operations that target ships at Bikini lagoon be decommissioned "or placed out of service" because they "cannot be made absolutely safe to board in the near future." When damage could be assessed it would be decided whether to sink them or return them to Pear Harbor. Nevertheless, ten ships would be decontaminated as "consistent with safety" for use in the third test.

Document 28

NTA, NV0140649.

A proposal to operate the machinery and engines of contaminated warships in the target area led Warren to urge that "no further work" be done on any of them unless "adequate and well organized safeguards were in place." Even though gamma radiation had decreased, alpha emitters persisted which were the "most poisonous chemical known." Fission products could be found in ventilating systems, undisturbed dust, painted surfaces, ship decks, and wooden surfaces. Moreover, people, food, clothing, hands, and food were also contaminated "in increasing amounts each day."

Document 29

RG 59, Records of the Department of State, Records of the Special Assistant to the Secretary for Atomic Energy and Outer Space, General Records Relating to Atomic Energy Matters, 1948-1962, box 77, 18. Weapons: 12. Testing: g. Proving Grounds-Bikini-General.

This fascinating account of discussions with Simon Peter Alexandrov was based on an interview with a leading marine biologist, Paul Galtsoff, who had been trained in Czarist Russia and escaped at the time of the Bolshevik revolution and eventually became an employee of the Department of the Interior. Galtsoff's account sheds focuses on Alexandrov, a Soviet loyalist who displayed considerable hostility toward the United States. Galtsoff believed that both Alexandrov and the other Soviet observer Mikhail Mescherayakov were both members of the NKVD, in part because Alexandrov had stated that he reported directly to Beria, the NKVD's former chief and the director of the Soviet atomic program. According to this account, among the statements that Alexandrov made was that the purpose of the Bikini test was "to frighten the Soviets," but they were "not afraid," and that the Soviet Union had "wonderful planes" which could easily bomb U.S. cities. Galtsoff speculated that these statements represented a "deliberate attempt to transmit a subtle bluff to the U.S. government."[18]

Galtsoff reported that when the observers group arrived at San Francisco, Alexandrov dictated a press statement that the Soviet Union had made progress in developing atomic energy and "that very soon we will have everything that you have in the United States." Further, the Soviet Union was planning to have a "demonstration" of an atomic bomb and that he had gone to Bikini "to see how it was carried out." When the Soviet Union had the bomb it would invite foreign observers to a remote location, such as Siberia, where the test would be held. United Press International reported that Alexandrov had stated that Moscow already had the bomb, while Alexandrov denied that he had made "such a flat statement"; according to UPI, his interlocutor insisted that the statement had been made. In any event, Alexandrov's statement made it public knowledge that the Soviet Union had begun a weapons program.[19] Galtsoff's personal account gives a different spin, saying that Alexandrov had denied saying anything about Soviet atomic progress or inviting observers. According to Galtsoff, the Soviet consulate in San Francisco soon assigned a minder to Alexandrov for his return trip to New York.

Also of interest in this report is the discussion of the relationship between the Soviet and Polish observers: the Poles told Galtsoff that they feared the Soviets and had been "forced" by Warsaw "to cooperate with the Russians." One of the Poles, Anrezej Soltan, was reading the recently published book, I Chose Freedom, by the Soviet defector Viktor Kravchenko and begged Galtsoff "not to let the Russians know he had the book."[20]

Who prepared this report is also a mystery, but whoever it was had access to Kravchenko, who answered his question about the NKVD role in Soviet industry.

Document 30

RG 218, Central Decimal Files, 1948-1950, box 231, CCS 476.1 (10-16-1945), Section 9, Part 1

While the Navy was confronting the problem of contaminated target ships, on 7 August General Leslie Grove recommended that the Joint Chiefs cancel the third test. For Groves the two tests had demonstrated what was already known: that a "properly placed" air burst could destroy a capital ship and that an atomic bomb "provides the same degree of energy transfer from bomb to water as to bomb to air." The deep underwater third test would only be a "test of deep water shock hydrodynamics" which would not even demonstrate significant personnel casualties because the radioactivity would be "lost under water." Moreover, Groves argued that Los Alamos did not have the personnel needed to assemble a bomb "without seriously interfering" with current research and development work." It is imperative that nothing interfere with our concentration of effort on the atomic weapons stockpile." Admiral Blandy disputed those arguments but the Joint Chiefs agreed that the third test would interfere with research work at Los Alamos and that "the major objectives of the atomic bomb tests have been achieved from the information and data obtained from Tests 'A' and 'B.'"

Document 31

NTA, NV0 140671.

William Myers, a radiation expert at Ohio State University, sent Warren a memo on his experience after the Baker test. It began with his recommendations on how the experience at Bikini could be used to create a Civilian Atomic Bomb Monitoring Corps to survey radiological conditions after an atomic attack on the United States. Toward the end of his memorandum, Myers observed that the contamination of his clothing led him to "believe that much air-borne (probably as aerosols) beta-emitting material was spread around by the Baker bomb." He was especially concerned about that "which entered the lungs since a man at rest on the ships would have breathed in about 400-500 liters of the contaminated air per hour." Stating that he was "not an alarmist" and that "hind-sight is much better than foresight," he did not believe that anyone sustained any "permanent" injury from Baker. Yet he was concerned about the long-run impact because "many of us probably received much more penetrating, ionizing radiation than instruments of very low beta-sensitivity were able to record."

Document 32

RG 19, Records Relating to Operation "Crossroads," box 5, A9 Reports.

According to Commander Edgar H. Batcheller, one of the lessons of the Bikini tests was that compared to large fixed targets, ships were less vulnerable to atomic attacks because they could be dispersed more widely to limit vulnerability to a detonation. Therefore, the atomic bomb "seems much more valuable for employing against strategic targets in a country's industrial and population centers rather than for use tactically against a ship or well dispersed formation of ships." Nevertheless, ships could be more vulnerable at port facilities and coastal industrial areas.

Batcheller believed that the "performance of the target vessels in withstanding the attack was generally good," in that "ships were not atomized" and did not "disintegrate." Except for the Japanese ship Nagato, those which sunk were carrying loads "greatly in excess of that which they were designed to withstand." Batcheller argued that "the test indicated our current design of ships structure is sound and adequate and that future developments should be evolutionary," e.g. in improving weak points, for which he made recommendations in the concluding section.

Comparing Able and Baker, the "material damage" caused by the latter was "was less widespread than that caused by the air burst it was in most cases much more severe in its effect of the ship's military effectiveness." After reviewing the damage caused by the aerial and the underwater detonation, Batcheller observed that the "radiological contamination of the target vessels which followed the underwater burst was the startling and threatening aspect of either test."

Document 33

RG 218, Central Decimal Files, 1948-1950, box 231, CCS 476.1 (10-16-1945), Section 9, Part 2

Over a year after the Bikini tests, the JCS Evaluation Board produced its final report, a review of the test results and their implications for national policy. One of the board members, Admiral Ralph Ofstie, showed a draft to a colleague, who commented that “It scared the hell out of me.” Readers of the conclusions and the text of the report [PDF pages 20-49] will quickly understand why. Drawing on their understanding of the blast, fire, and radiation effects of the Able and Baker tests, the Board concluded that “If used in numbers, atomic bombs not only can nullify any nation’s military effort, but can demolish its social and economic structures and prevent their reestablishment for long periods of time. With such weapons, especially if employed in conjunction with other weapons of mass destructions, for example, pathogenic bacteria, it is quite possible to depopulate vast areas of the earth's surface, leaving only vestigial remnants of man's material works.”

The Board took it for granted that the United States had to retain its “dominance in the ability to wage atomic warfare, the loss of which might be fatal to our national life.” While it favored a peace based on international cooperation, “agreement and understanding,” until such circumstances existed, “this nation can hope only that an effective deterrent to global war will be a universal fear of the atomic bomb as the ultimate horror in war.” Therefore, in the absence of “permanent peace” the Board favored the “immediate and continuous preparation for the contingencies of atomic warfare is the part of prudence.” Thus, the idea of a permanent arms race was built into the reports’ conclusions.

The Board supported the creation of an intelligence service that could help provide warning of attack, but it also favored preventive war under some circumstances measures will be the only generally effective means of defense, and the United States must be prepared to employ them before potential enemies inflict significant damage upon us.” Even the production of fissile material by an adversary could be a cause of war. According to the Board, as commander-in-chief, the President’s duty was defense against “imminent or incipient atomic weapon attack.” Nevertheless, as long as the United States had a “democratic government,” Congress would have war making powers and was obliged to define what “imminent” or incipient” meant in practical terms: “What constitutes incipient attack it is the responsibility of the Congress to explore and define so that it may draft suitable orders to the Commander-in-Chief for utilization of our armed forces should we be under the menace of an atomic weapon attack.” In other words, Congress would authorize a preemptive or preventive war by the President.

The discussion of war-making powers was the report’s most deeply controversial feature and when the possibility of public release was under discussion, the Joint Chiefs wanted to excise those portions. The proposed excisions are evident in the version of the report published herein. Nevertheless, the entire report was so hot that senior officials in the State Department and Defense Department strongly objected to its release. The document stayed suppressed until it was declassified in 1975. [21]

Notes

[1] . This text, and the selection of documents, relies heavily upon the most comprehensive and wide-ranging account of Crossroads, Jonathan M. Weisgall’s Operation Crossroads (Annapolis, Naval Institute Press 1994). Also helpful was the chapter on Crossroads in James P. Delgano’s Nuclear Dawn: the Atomic Bomb from the Manhattan Project to the Cold War (Botley, Oxford, Osprey Publishing, 2009), 138-162.

[2]. Stephen Schwartz et al., Atomic Audit: The Costs and Consequences of the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Program, 1940-1998 (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1998), 99-101; e-mail from Stephen Schwartz, 12 July 2016.

[3] . James B. Hershberg, James B. Conant: Harvard to Hiroshima and the Making of the Nuclear Age (Stanford, Stanford University Press, 1995), 267. Quotations by Assistant Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Robert Lee Dennison and Army Air Force commander Carl Spaatz, Melvyn P. Leffler A Preponderance of Power: National Security, the Truman Administration, and the Cold War (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992), 116.

[4] . The Soviet observers, Alexandrov and Mescherayako, sent reports to Moscow that were incorporated into a memorandum for Molotov on the Bikini tests. The comments on the first test indicated “general disappointment with the results of the explosion.” See David Holloway, Stalin and the Bomb: The Soviet Union and Nuclear Energy, 1939-1956 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994), 227.

[5] . Manhattan District History, Book VIII, Los Alamos Project (Y) – Volume 3, Auxiliary Activities, Chapter 8, Operation Crossroads (n.d., ca. 1946), as cited in Restricted Data: The Nuclear Secrecy Blog.

[6] . Quotations from Barton H. Hacker, The Dragon’s Tail: Radiation Safety in the Manhattan Project, 1942-1946 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 136-137.

[7] . Ibid, 138 and 140.

[8] . Schwartz, Atomic Audit, 405-406.

[9] . Weisgall, Operation Crossroads, 107-108.

[10] . Martin Sherwin and Kai Bird, American Prometheus, 332, 350.

[11] . A subsequent public statement indicated Joliot-Curie’s distress over the Smyth report.

[12] . Additional intelligence information was gathered from Alexandrov. According to a

message to Secretary of State Brynes from Fred Searls, a member of the U.S. delegation to the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission, “intelligence reports of declarations by Alexandrov at Bikini” indicated that the Soviets lacked “workable high-grade deposits” of uranium.

[13]. Leffler, A Preponderance of Power, 114-116.

[14]. Robert S. Norris, Racing for the Bomb: General Leslie R. Groves, the Manhattan Project’s Indispensable Man (South Royalton, VT: Steerforth Press, 2002), 673, note 32.

[15] . Weisgall, Operation Crossroads, 233.

[16] . Hacker, The Dragon’s Tail, 145-146.

[17] According to the Defense Nuclear Agency report on Operation Crossroads, Warren did not have direct evidence about plutonium particles but “indirect evidence” convinced him of the danger. Thus, it was “prudent and conservative” to decide to bring decontamination work to a halt. See pages 116 and 118.

[18] . That several Soviet officials had witnessed a U.S. nuclear test gave them considerable standing. Beria did not want any slip-ups in the first Soviet test and insisted that the scientists replicate the U.S. “Fat Man” design. Immediately after they staged their initial test, “First Lightening” in August 1949, Beria reportedly called Mescheryakov and asked him, “Was it similar to the American one? Very? We didn’t muff it? … Everything was the same? Good. That means we can inform Stalin that the test took place successfully.” See Gordin, Red Cloud at Dawn, at 176.

[19] . For a press account, see “Soviet Already Has Atomic Bomb Ready to Test, Russian Scientist Implies,” The New York Times, 13 August 1946. See also Michael D. Gordin, Red Cloud at Dawn: Truman, Stalin, and the End of the Atomic Monopoly (New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 2009), 134-135.

[20]. For Kravchenko and his life before and after his defection, See Gary Kern, The Kravchenko Case: One Man’s War On Stalin (New York: Enigma Books, 2007).

[21] . Hershberg, James B. Conant, 389.