Washington, D.C., March 3, 2022 – While Russian troops invaded Ukraine this week, the Russian Supreme Court turned down the appeal by the legendary human rights group Memorial against the “liquidation” orders intended by the authorities in December 2021 to put the society out of business, after more than 30 years’ work documenting the victims and the previously secret history of Soviet repression.

The European Court of Human Rights on December 29, 2021, had halted the implementation of the “liquidation” orders against the Memorial Society and the Memorial Human Rights Centre, pending arguments over whether Russia’s “foreign agents” law violates the European Convention to which Russia is a signatory. However, the Russian Supreme Court appeal ruling this week, and even more so, the Russian assault on Ukraine, demonstrates that Russia will not comply with the European Court on this case, nor likely on the many forthcoming cases about Russian war crimes against Ukraine.

The National Security Archive today pays tribute to Memorial’s indomitable spirit and everlasting legacy by publishing documents and photographs that resulted from the Archive’s long-standing partnership with Memorial. Leading the posting are three reports from the Memorial archives written by then-ombudsman for human rights Sergei Kovalev in 1994 and 1995, describing the Russian war in Chechnya in terms directly parallel to what the world is seeing in Ukraine today: Indiscriminate targeting of civilians, ill-informed and badly supplied Russian conscript soldiers, and a Russian leadership more like a “mafia organization” than a government.

Also included in today’s tribute to Memorial are examples of its extraordinary encyclopedias tracking every single prison camp in the Soviet Gulag, and the careers of every single NKVD and KGB officer who served Stalin. Photographs include the late chairman of Memorial, Arseny Roginsky, walking Archive staff and Russian specialists through the actual barracks of the Perm-36 prison camp that had been preserved by Memorial, during the last Pilorama festival at that camp in 2012 before the authorities shut down the site.

The Memorial archives contain thousands of records on Soviet and Russian dissent, ranging from the underground publication of critical literature despite censorship, to the KGB’s persecution of the Moscow Helsinki Group. The courage and independent spirit evident in that decades-long dissident history, as well as state repression and cruelty, emerged again in the past week, as thousands of protesters were beaten and arrested on the streets of Moscow and 100 other Russian cities, saying “No to war.”

Today’s publication also includes Memorial’s detailed report on the Russian Supreme Court hearing on February 28, 2022. Although the ostensible legal charges were about insufficient “foreign agent” labeling on Memorial’s social media posts, prosecutors revealed their real motives during the arguments in December, claiming that Memorial “distorts memory about the War,” “rehabilitates Nazis,” and “creates a false image of the USSR” and Russia as terrorist states.

Elena Zhemkova, Memorial’s director and one of its founders in the 1980s, commented during a Zoom call this week, “Our organization is destroyed but our work continues, to find the families of the victims, to keep the memory of the political repressions, to contribute to the rehabilitation of the wronged, and this work is not going to disappear.” Zhemkova added, “We are not thrown back to square one, because so much of what we have gathered is now digitized and distributed widely and part of the world’s heritage. But we are in a different reality right now: not just Memorial but all people in Russia who speak openly and express their disagreements with the authorities face repressions.”

Zhemkova described the purpose of Memorial: “Our initial thought, before even gathering documents or erecting monuments, was to prevent such repressions from ever happening again. Neither memory nor human rights have borders, and now we start our long journey to bring Russia back to civilized humanity.”

Ivan Pavlov, the noted Russian human rights lawyer who has worked with Memorial and with the Archive, wrote on Facebook about the December court order that “Memorial began the human rights defence era in our country and it is today ending it. The regime is demonstrating to us that from now on in the civic and information realm there must be nothing, no media projects, no educational initiatives or civic moves. What is left is to either reject any activism, however minimally compromising, or fall under the steamroller of repression.”

The Documents

Document 1

Memorial Society Archive, Moscow, Russia

Document 1a

Memorial Society Archive, Moscow, Russia

This document is a summary of a telephone report from Sergei Kovalev, the human rights commissioner of the Russian Federation, to Ivan Rybkin, chairman of the Duma, as dictated to N. I. Semina, Kovalev's assistant. Kovalev is calling from Grozny, on a trip with a group of Duma deputies to investigate the situation and the possibility of a peaceful resolution. The parliamentary delegation traveled to the areas of Achkoy-Martan and Novy Sharoy in Chechnya. The group had conversations with Russian soldiers, who were reportedly "distinctly" aware that the "development of the conflict" would lead to "increasingly more serious casualties among the civilian population," about which the soldiers had an "obvious" negative attitude. Kovalev had witnessed the bombing of the building that housed the Chechen Republic's Department of State Security and noted that the central authorities failed to mention the fact that it was located in "the midst of the heavily populated central area of Grozny." Kovalev describes a "chasm of misunderstanding" between the Russian authorities and the Chechen side and believes that "a crime is being committed not only against the [Chechen] people, but also against Russian soldiers."

Document 2

Memorial Society Archive, Moscow, Russia

Document 2a

Memorial Society Archive, Moscow, Russia

This letter from Commissioner for Human Rights of the Russian Federation Kovalev to Prime Minister Chernomyrdin addresses Chernomyrdin's January 16 speech on the conflict in Chechnya. Kovalev, who at the time was still in Grozny but about to fly back to Moscow, is writing to share his four key points for the negotiation process that he sees necessary to end the war. The first is the "de facto recognition of the administration of General Dudaev as one of the parties to the negotiations," since the administration "is still recognized by a large part of the Chechens." The second is the "gradual termination of military conflict, without setting preconditions at any given stage," as Kovalev believed that "even minimal success" would have "enormous public and international resonance," which would in turn "stimulate the continuation of the process."

His third thought concerns resolving "humanitarian issues," such as prisoner exchanges and assistance for civilians. His final point addresses the importance of "the quickest unveiling of the specific government plan," as well as the necessity of the "openness and transparency of the federal government's position in the negotiations." Kovalev indicates that he will be available for a personal meeting with Chernomyrdin when he arrives in Moscow.

Document 3

Memorial Society Archive, Moscow, Russia

Document 3a

New York Review of Books

This fiery letter fits all too closely today’s circumstances if one substitutes the name Putin for that of Yeltsin, and the territory of Ukraine for that of Chechnya. In January 1996, after 13 months of bitter confrontation with Russian President Boris Yeltsin over the war in Chechnya, Kovalev decided to resign his position as Russia’s first ombudsman. By this time, Yeltsin had already dissolved the President’s Human Rights Commission, but Kovalev kept it functioning. In this letter, the early supporter of democratization blames Yeltsin for abandoning the hope of Russian democracy. Kovalev does not absolve himself and admits that he supported Yeltsin in his use of force against the Parliament in October 1993, but points to signs of sliding toward authoritarianism due to Yeltsin’s power grab (via the 1993 Constitution) and demonization of the opposition. From 1993 on, Kovalev writes, instead of implementing democratic reforms, Yeltsin “revived the blunt and inhumane might of a state machine that stands above justice, law, and the individual.” Kovalev indicts the Russian president for abandoning transparency and reviving excessive secrecy, and for selecting government officials on the basis of personal loyalty. In Kovalev’s view, Yeltsin’s “policies compromised” even the words “democracy” and “democrats.”

Speaking about the upcoming 1996 elections, Kovalev says that Yeltsin is no better than his Communist (Gennady Zyuganov) and nationalist (Vladimir Zhirinovsky) opponents and that “if we have to choose among you, it will be like choosing which mafia organization to apply to for protection,” and so he tells the president he is not going to vote for him. Above all, he blames Yeltsin for unleashing the murderous war in Chechnya, which claimed thousands of civilian lives. As a former close supporter, Kovalev adds a very personal note; he tells Yeltsin that he has “lost [his] soul, that [he was] unable to evolve from a Communist Party secretary into a human being.” As the translation notes, the letter was first published in Izvestia and then in The New York Review of Books, translated by Catherine A. Fitzpatrick.

Document 4

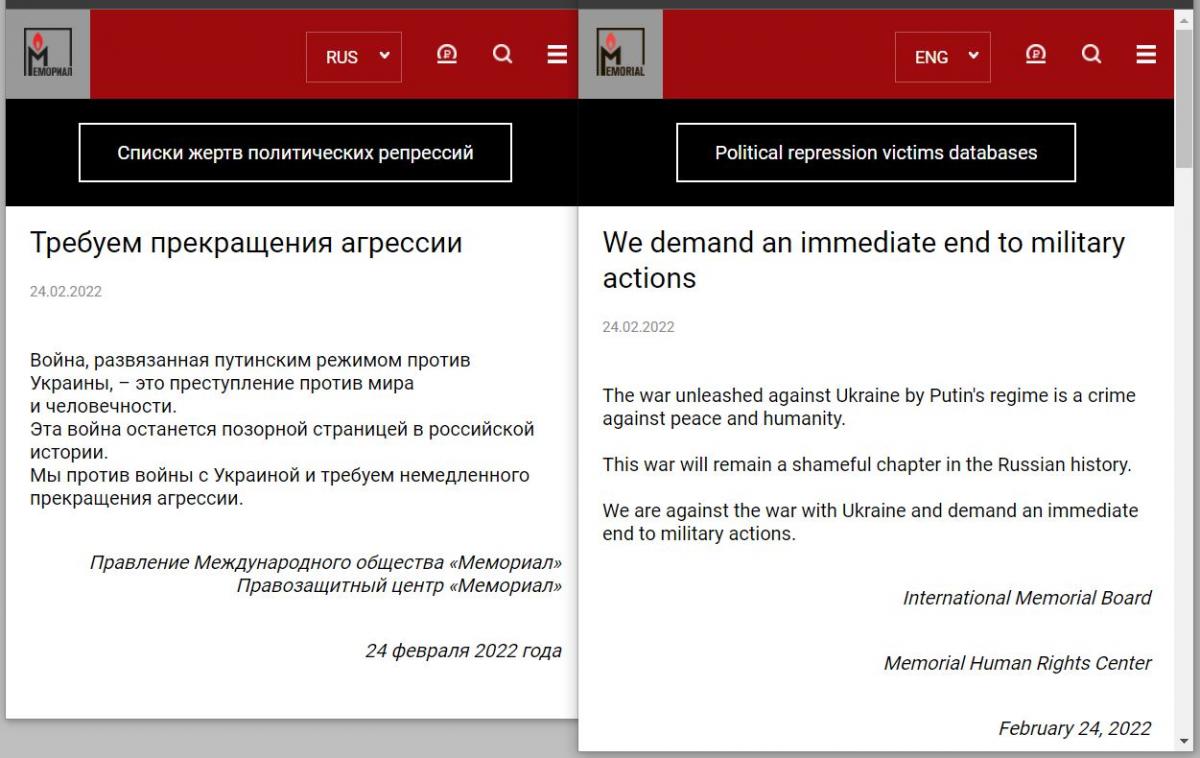

Memorial, https://www.memo.ru/en-us/memorial/departments/intermemorial/news/690

This report from Memorial’s Internet homepage this week describes the organization’s arguments to the Russian Supreme Court on the appeal of the “liquidation” order. Memorial’s director, Elena Zhemkova, points to what she calls “the real reasons” for the prosecution – that Memorial “speaks of responsibility and preserves memory, including about crimes, and the liquidation of an organization that helps us not repeat the crimes of the past and not make mistakes today is harmful to all people living in Russia.” Memorial’s lawyers point out the flaws in the prosecution’s case and predict that the state could “slide into a second edition of the Soviet Union.” The report also includes links to the full texts of the appeal, of the December 2021 initial decision by the court, and of the original November 2021 prosecution complaint.

Political repression victims databases

- base.memo.ru: Victims of political terror in the Soviet Union, a general database

- stalin.memo.ru: Stalin's execution lists, 1937–1954

- mos.memo.ru: Repression victims executed in Moscow

- pkk.memo.ru: Political Red Cross archives, 1918–1922

- "Ubity v Katyni": a PDF version of the book containing data on the Polish POWs who were held at an NKVD camp in Kozelsk and fell victims to the Katyn massacre

- "Ubity v Kalinine, zakhoroneny v Mednom": a PDF version of the book containing data on the Polish POWs who were held at an NKVD camp in Ostashkov.

- Book 1 (pdf) Book 2 (pdf) Book 3 (pdf)

- histor-ipt-kt.memo.ru: Repression against the True Orthodox (Catacomb) Church members, late 1920s –1970s

- cathol.memo.ru: Repression against the Catholic Church members, 1918 – 1980s

- openlist.wiki: Open list project